From collection Creating Acadia National Park: The George B. Dorr Research Archive of Ronald H. Epp

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

Page 62

Page 63

Page 64

Page 65

Page 66

Page 67

Page 68

Page 69

Page 70

Page 71

Page 72

Page 73

Page 74

Page 75

Page 76

Search

results in pages

Metadata

[Series III] Clubs of Greater Boston

CLUBS OF Greater Poston

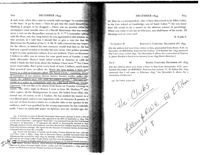

8/3/09 Dorr (milain f

Antigated into becoming

2/20/09

GEORGE B. DORR: SOCIAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP

Boston:

Engineer Club Not a member though visited as guest.

Saturday Club Not a member though Samuel G. Ward was a founder.

Somerset Club 1874-1937

Tavern Club 1904-1932

Union Boat Club 1889-1913

University Club No evidence of membership though visited as guest

Union Club No evidence of membership though F.C. Gray and Samuel G. Ward

were founders at the outset of the Civil War.

New York, NY

Harvard Club. No evidence of membership though visited as guest.

Washington D.C.:

Cosmos Club 1921-1935

Dorr Clubs821

4600 00208 6L

Social History of

CONTENTS

The

Greater Boston

I. INTRODUCTION

3

2. THE DINING CLUBS

7

Clubs

3. CLUBHOUSES

16

4. UNION AND SOMERSET

24

5.THE INTELLECTUAL CLUBS

31

6. CLUB GOVERNMENT

46

Alexander W. Williams

7. THE LUNCH CLUB

49

8. COUNTRY CLUB

52

9. TENNIS & RACQUET

70

10. THE YACHT CLUBS

77

II. WOMEN'S CLUBS

81

I 2

THE HARVARD COLLEGE CLUBS

87

13. FOOD AND DRINK

103

14. PROHIBITION AND THE CLUBS

114

15. ODDMENTS

120

16. ENVOI

125

17. THE SOCIAL REORGANIZATION OF BOSTON

by Nathan C. Shiverick

128

18. A MINIATURE COOKBOOK OF CLUB FOOD

144

Soups 145; Entrées

149

Fish & Shellfish

152

Poultry & Game

159

BARRE PUBLISHERS 1970

Meat 163; Vegetables

170

Desserts

174

Photographs following page

88

Z

1

note: see Helen Home's The Gentle americans

(1965) for remarks about child life

INTRODUCTION

(chapter 5,11,+18). see also Robert

grant, Fourscore (Pp. 199f.).

RECENTLY I wrote two papers on the social history of the Club of

Odd Volumes, which enjoyed a mild success, enough at any rate to

cause the committee on publications to decide to issue them as a

book under the Club's imprint. This in turn prompted several peo-

ple, among them Walter Whitehill, who had done an introduction

to the Social History, to suggest that I go ahead and write the his-

tory of the Greater Boston clubs. "Even if very few people read it,

it wants doing" seemed to be their argument for my tackling the

job. Most club histories, when they have been written, were usually

published privately for the enjoyment of and as a service to their

members. These little volumes are consequently often hard to come

by, and it seemed a useful idea to assemble such fruits as they con-

tain into one pudding.

I have been particularly anxious to approach this task from the

point of view of social history, for therein, it seems to me, lies

whatever value the project has. Some years ago a handsomely de-

signed book called Leather Armchairs, by Charles Graves, was

published in England and in this country (New York: Coward

McCann, 1964). It was intended to be a history of the London

clubs, though it turned out to be more of a guide than a history. It

proceeded chronologically from the earliest club, White's (1693),

down to the most recent, the 1962 gambling clubs, Quent's and

Clermont. It gave in each case the size of the membership, the town

and country dues, the initiation fees, charges for meals and rooms.

Introduction [5]

The Greater Boston Clubs

3

tended to have better food than restaurants or hotels, on whom the

Now, this kind of information is perhaps valuable for someone

murrain of Prohibition lay more heavily.

thinking of joining a club, but, especially in the shifting prices of

Where to draw the line in this survey? I would include chiefly

clubland, in a book it begins to become inaccurate from the day of

only clubs that had a permanent residence before 1918 and limit

publication.

the country clubs to the half dozen earliest. The famous Boston

Leather Armchairs starts well with a lively preface by P. G.

dining clubs, such as the Saturday, the Thursday Evening, and the

Wodehouse, creator of the "Drones" Club, a competent introduc-

Wednesday Evening of 1777, should be touched upon, for they are

tion, and all that rich eighteenth century material which took place

an integral and important part of Boston club life. But they have

within the walls of White's, Brooks's, and Boodle's. But thereafter

no permanent houses of their own and gypsy about to members'

the book, with its statistics and name-dropping, becomes dull. I

homes, other clubs, and even restaurants.

hope to avoid that, of course, but I believe it can only be done by a

It may be asked why the Harvard College clubs should be given

quite different approach and method than those chosen by Charles

Graves.

much attention, since they now play no great role in university life.

Their role through officers and members in the life of most of the

Greater Boston is a very good locality for club history. In the

Greater Boston clubs is immense, if not always openly acknowl-

first place there are a great many clubs, and some of them are old as

edged. For example, of the 550 members of the Somerset Club listed

clubs go in America. In Cambridge the Hasty Pudding-Institute of

in the 1967 yearbook, there were some 390 Harvard graduates, and

1770 and the Porcellian Club have their origins in the eighteenth

of these, 300 at least were members of final clubs in Cambridge. Of

century. If you allow their origins as fraternities, at least four other

the Somerset's officers since 1852 well over half fall into this cate-

Sincerel

Harvard "final" clubs date from the 1830S and 40s. The Somerset

gory. It is common practice when proposing candidates in the

Club celebrated its 100th anniversary in 1951, though it had started

Somerset or Tennis & Racquet to mention, en passant, what club

as the Tremont Club in the 1840s, which, to be sure, is not as old as

they belonged to across the Charles. The Tavern is more squeam-

the Philadelphia Club (1834), the Union in New York (1836), and

ish. A long-time secretary of it writes me: "Harvard final clubs

the Boston Club in New Orleans (named for the card-game pred-

are a nasty word to our election committee and never mentioned at

ecessor of whist and bridge, not in honor of Ben Butler.) Boston's

its sessions." Nevertheless, out of a total membership in 1967 of

Union Club came along in 1863. But the great dam-burst of club

240, there were twenty-three from the Fly, twenty from Porcel-

founding occurred in the decades 1875-1895. The St. Botolph,

lian, fifteen each from the A.D. and the Spee, fourteen from the

Tavern, Algonquin, Puritan, University, Odd Volumes, India

Wharf Rats, Country Club (Brookline), Myopia (Hamilton),

Delphic, and doubtless a few from other clubs. So, you could say

that over a third of the Tavern membership was drawn in a given

Dedham Polo, Boston Athletic, City Club Corporation (Lunch),

year from the Harvard final club pool. "Nasty word," indeed!

Nahant, and Signet (Harvard), Mayflower (women), and Essex

This, and the fact that at least five of them, Porcellian, A.D.,

County all date from this period.

Fly, Spee, and Delphic, had permanent residences well before the

Boston is also a good place in which to collect club history be-

turn of the century, should justify their story in a later chapter.

cause it has always been a town with a considerable scarcity of fine

Their membership lists also turn up some surprises, at any rate for

restaurants, especially in the Prohibition period. (Boston is still not

those who regard them solely as snobbish drinking dens. Of the five

a notable restaurant city.) When they did not eat at home, people

Harvard Presidents of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt was

were apt to patronize their club. And you could, in Prohibition as

in the Porcellian (and Fly as a waiting club), Franklin D. Roose-

well as now, have a drink respectably in your club, by means of

velt was in the Fly, and John F. Kennedy was in the Spee. And, to

various subterfuges which will be discussed later. Therefore clubs

rticle: The Old Boys' Clubs. The Harvard Crimson Online

Page 1 of 11

april 27, 2000

table of

(111 is the weekend magazine of the harvard crimson.

CONTENTS

THE OLD BOYS CLUBS

final clubs are only the tip of the iceberg.

fm journeys to the heart of boston's elite club scene.

Samuel R. Hornblower

Years ago, a young Bostonian's quest for status

began the moment he enrolled at Harvard. He

needed to enter the right final club, the right

country club, the right Boston club, the boards of

the right charities and finally, if he reached the

ziggurat of Boston society, Harvard's almighty

Board of Overseers. His children would, in their

turn, need to go to the right boarding schools, join

the right societies and know whether or not the

right wines were being served at the right time.

Final clubs were anything but final. After

graduation, Harvard society moved on to the

plethora of elite clubs that still draw an exclusive

membership in twenty-first century Boston.

The Somerset, Union, Tavern, Algonquin, St.

Botolph and-for women-Chilton Clubs

represented the hub of The Hub. The stature of

these clubs was SO elevated that no one could

aspire to the city's first circle of power without

joining one, or better still, several.

Today, in Beantown, the rules have changed.

As institutional stability vanishes, one no longer

need frolic through WASP theme parks to claw

one's way to the top. Other avenues to power and

high society avail themselves. And while identity

politics have by no means demolished these

hallowed institutions, "diversity" is upon them.

Just over a generation ago, Irish Catholics, Jews

and blacks were not considered worthy of

http://www.thecrimson.com/fmarchives/fm 04 27 2000/article11A.html

9/8/2005

rticle: The Old Boys' Clubs. The Harvard Crimson Online

Page 2 of 11

membership. A woman's place was, well, in her

own club, the Chilton-not in the den of men, in

any event. At Myopia Hunt Club on Boston's

North Shore, women golfers were forbidden to

enter through the main door or linger in the

lounge.

More than a century ago, these reservoirs of blue

blood began as a mansion away from one's

mansion, the alternative to the city's less-than-

appealing selection of restaurants and too-public

hotels. These were places where men could smoke

the mild cigar and sip a fine brandy while playing

cards and catching up on the news from Europe.

"There was a whole class of people that didn't

have to work," says Hugh Davids Scott Greenway

'71, a member of both the Tavern and the

Somerset.

PY

Among their descendents in today's fast-paced

urban Boston, the old ways, though not entirely

extinct, are fast fading. "Lifestyles have changed,"

says Robert Minturn '61, a member of the

Somerset Club. "Young people work-they have a

sandwich at their desk and then go to the gym for

40 minutes. They won't spend an hour and a half

at the Somerset in the middle of the day." Even the

older crowd is more likely to power-lunch at

Radius and later cap the day by working it off on

the squash courts at the Harvard Club. And

dinner? If anywhere, it will be back in suburbia

with the kids. "It is very difficult for the

Somerset." says James Righter '58. "There are no

sports, no games The Somerset is great for retired

people." Indeed the average member of most of

these clubs is in their late fifties and sixties. Years

ago, former Somerset President Richard S.

Humphrey '47 was once quoted as saying, "One

hundred years from now, we'll all be out of

business and long forgotten. I just don't think that

there is going to be

a need for a place like this." From Humphrey, the

pessimism may be understandable. As Minturn put

it, "Rickey said that? Well, yeah, he's A.D."

To gain admission to one of Boston's clubs,

candidates attend a number of dinners over the

course of several months. "Membership selection

is an elaborate process," says Minturn, "They

sound people out and don't officially propose them

until the very end. This is partly to avoid an

embarrassment."

Members use the clubs for both business and

social purposes. The intimate old-Boston

ambience appeals to out-of-towners who are often

brought up as guests. "At the Somerset," St.

Botolph members have long chuckled, "they have

the money; at the Union, they manage it; at the

Algonquin, they're trying to make it; and at the St.

Botolph, they enjoy it. The Chilton and Somerset

http://www.thecrimson.com/fmarchives/fm 04 27 2000/article11A.html

9/8/2005

article: The Old Boys' Clubs. The Harvard Crimson Online

Page 3 of 11

are primarily social. Even discussing business in

the morning room used to bring a waiter with a

silver platter and a small card asking the offender

to refrain. "Even now," says Minturn, "flagrant

displays of briefcases and papers, are frowned

upon." Cell phones are a cardinal sin. At the

Algonquin, on the other hand, there are no such

qualms. "It is a business club," scoffs one member

of the Tavern. The St. Botolph and Tavern Clubs

are considered "artsy," and the Union "is full of

business lawyers." Boston's British heritage gives

the town, for better or for worse, a distinctly

clubby, if stratified atmosphere. Though many of

the traditio

ns and aims of these clubs were laudable in their

own day, they have inherited a dubious legacy of

snobbism and exclusion.

Election committees today struggle to attract a

politically correct pool of candidates. Minturn

insists, "there are plenty of people who are eager

to enjoy a great meal and good conversation." The

difficulty, though, lies in diversifying their

membership. "There just are not too many takers,"

says one club member, who asked not to be

named, "but it's understandable. If you were

black, you wouldn't want to stick out like a sore

thumb. My instinct is that the Somerset would be

delighted to have more, but my guess is that

[minorities] would not be too interested." A

Taverner, gave another explanation: "These clubs

are slow to reach out, but they've gone a long way

in that direction. The turnover in a university, for

example, occurs on a yearly basis. At the Boston

Clubs, on the other hand, the turnover is one

generation. People are there for 40 years-it takes

time to build under those circumstances." Insiders

contend that they are not attempting to mimic the

city's meritocracy in any way. "Is it a

meritocracy?"

one Somerset Club member asked. "Not

completely. Are [the clubbies] the people with the

money? No. Are they the dot.com barons? No.

They are the people who are thought to be

interesting." He continued emphatically: "It isn't

just Brahmins. I mean, my God! They've had New

Yorkers and Yalies as presidents!" Has it come to

this?

In July 1987, the Boston Licensing Board strong-

armed the elite Brahmin fraternities. They adopted

a rule calling for the revocation of the food and

liquor licenses of clubs that have more than 100

members, are used for business or professional

purposes and choose members on the basis of sex,

race, color or religion. The rule is worded to cover

only those few clubs that were used by members

primarily to conduct business over meals. Private

clubs with a social orientation, like the all-male

Elks clubs or the Knights of Columbus, are

exempt. Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

http://www.thecrimson.com/fmarchives/fm 04 27 2000/article11A.html

9/8/2005

Article: The Old Boys' Clubs. The Harvard Crimson Online

Page 4 of 11

specifically exempted private clubs. And since

private clubs traditionally have been

acknowledged as possessing First Amendment

protection from public-accommodation laws,

efforts to open their membership to women met

with little success in previous attempts. At the

licensing hearing, some of the haughty practices of

these all-male clubs were revealed. Alice

Richmond, former president of the Massachusetts

Bar Association, testified at

the time that she had been "humiliated" twice by

the practices of the all-male clubs. One time she

was forced to eat in a pantry while her colleagues

dined in elegance.

Licensing Board Chair Andrea Gargiulo did not

threaten to have any liquor licenses revoked until a

year later, when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a

challenge to New York clubs over a city rule

barring membership policies that were

discriminatory. This gave Gargiulo the green light.

Once the gates swung open, there was no

stampede of high heels, however. These bastions

of maleness are, it seems, a bit too male. The

parking is a hassle. There is too much booze. And

while women are, in fact, welcomed, they often do

not feel comfortable. Many of the first women

who joined resigned, citing a lack of time and

other priorities. Even so, many old-line members

place their hopes in sexual integration, praying

that it will keep these celebrated institutions from

fossilizing into their Beacon Hill and Back Bay

perches.

THE SOMERSET CLUB

42 Beacon Street

So exclusive is the Somerset Club, that one night

in January 1945 when the club caught fire, the

firemen ran through the front entrance before

Joseph, the club's legendary majordomo, ordered

them to go around back though the servant's

entrance while he continued serving members their

dinner. According to The Boston Post, "Although

the fires created considerable excitement among

the firemen and police who were detailed there,

the club members were not disturbed in their

dining room. They sat at dinner while the firemen

fought on the first, second and third floors. The

only recognition of the fire was the opening of one

window in the first floor lounge in the front of the

club to let some of the acrid smoke out. Otherwise

there was no sign about the tightly curtained

windows that anything unusual was happening

inside. The club members continued to come and

go, swinging their canes, undisturbed by the mass

of fire-fighting apparatus outside. One, more

curious than the rest, came out to the door with a

glass of W

hat looked like scotch and soda in his hand, but he

did not remain long."

http://www.thecrimson.com/fmarchives/fm 04 27 2000/article11A.htm

9/8/2005

Article: The Old Boys' Clubs. The Harvard Crimson Online

Page 5 of 11

The elegant Somerset Club, founded in 1851,

occupies the mansion of David Sears, Class of

1807, designed in 1819 by Alexander Parris and

built on the site of the farm formerly owned by

John Singleton Copley. Four large oval rooms, two

private dining rooms, a "morning room," a library

and an immense living room in the Directoire style

make up the core of the building. Beyond this

resplendent salon are the ivy strewn walls that

surround the Somerset's garden and terrace,

known as "the Bricks," where members and their

guests can relax and sip single malt scotch in utter

tranquility. The Somerset has traditionally been

the haughtiest and most prestigious of clubs, one

in which social pedigree is, ehem, de rigueur.

Some of the prominent members of the Somerset

roster include former Harvard Business School

Dean John H. McArthur, former Fletcher School

of Law and Diplomacy Dean Theodore Eliot '48,

former Watergate special prosecutor Archibald

Cox '34 and an aging roster of heavy-hitting

Yankees-including retired industrialist Louis

Cabot '43, former GOP gubernatorial candidate

John Winthrop Sears '52 and former state senator

William Saltonstall. They are always looking up

and down the Charles for suitable academicians

and physicians.

The 570 or SO members have no use for parvenus

and get-aheads trawling for business connections.

Applying directly is the surest way never to be

invited back. You will be "tapped" accordingly, if

they decide to show an interest in you. During

elections, it takes two black balls from the

governing board to earn a rejection. "You really do

have to know people," says Minturn.

After voting to admit women in the wake of the

licensing board decision, the Somerset Club

started by offering memberships to widows of past

members. As the wives of members played a large

part in the club, "the changes went almost

unnoticed," says Righter, "there were always

women around, women without men. The widows

were always invited." Some of the women who

joined the Somerset in the last several years

include the usual old New England families-

Spauldings, Sargents, Storeys, Lymans, Gardners,

Saltonstalls. In fact, two women now serve on the

club's board.

"Any club is by definition elitist. Even if it's the

Irish American Hiberian Hall. You are there

because you have something in common," Mintum

says.

THE UNION CLUB of BOSTON

8 Park Street

http://www.thecrimson.com/fmarchives/fm 04 27 2000/article11A.html

9/8/2005

rticle: The Old Boys' Clubs. The Harvard Crimson Online

Page 6 of 11

The oft-recounted legend of the founding of the

Union Club begins during the Civil War. In 1863,

as Col. Robert Gould Shaw, Class of 1860, and the

54th all-Negro regiment was marching past the

Somerset Club, the members pulled down their

blinds and hissed in disapproval. Shocked and

horrified, Norwood Penrose Hallowell, Class of

1861, second-in-command of that regiment,

reportedly led a group of his friends out the front

door and formed the Union Club just down the

street. Not until 1952 would a Hallowell finally

agree to join the Somerset.

This tale is greatly exaggerated. In fact, the

greatest number of defections from the Somerset

occured, not in 1863, but in 1865, following the

death of Lincoln. Throughout the Civil War, a

faction of the club was upset by the unpatriotic

sentiment of their fellow clubbies who attacked

Lincoln for his policies and ridiculed his person.

Though there is no hard evidence pertaining to this

great walk-out, Alexander Williams, chronicler of

the Boston clubs, hypothesizes that an impolitic

member may have risen and given a toast to John

Wilkes Booth. As one of the founders of the Union

Club would later remark, "We wanted a place

where gentlemen could pass an evening without

listening to Copperhead talk."

Since then, the story has been the Union Club's

gradual slide down the slope of Boston society. It

has long been described as the "Rodney

Dangerfield of Clubs." Today the club is overrun

by lawyers. The Union Club occupies the original

mansion of Amos Lawrence on No. 7 and 8 Park

Street. The upstairs dining rooms each have a

magnificent view of the Commons to the west.

THE ALGONQUIN CLUB

216 Commonwealth Ave.

The Algonquin is the most grandiose of the city's

clubs, the only one with a house designed

especially for its own use, rather than a converted

residence. Its massive granite exterior displays two

stories of porticoed balconies. The inside boasts an

enormous second floor reading room and a

massive formal dining room on the fourth floor

with 50-foot vaulted ceilings. The fifth floor offers

sleeping accomodations. Unlike clubs like the

Somerset, the Algonquin Club, since its founding

in 1886, is all about business. The Club was

founded by General Charles H. Taylor, the same

man who resurrected the Boston Globe.

Prestige-wise, the Algonquin ranks second to the

Somerset. Family bloodlines are not as

consequential as the corporate credit lines.

Capitalism proves itself in the Algonquin to be the

great equalizer-in the early '80s, the club's

http://www.thecrimson.com/fmarchives/fm04 27 2000/article11A.html

9/8/2005

Article: The Old Boys' Clubs. The Harvard Crimson Online

Page 7 of 11

membership was predominantly WASP, but today

its thousand members reflect the growing racial

diversity of the city's corporate population.

Some of its prominent members include former

President of Boston University John Silber, former

Bank Boston CEO Ira Stepanian, former Boston

Herald GM Patrick Purcell, nightclub owner

Patrick Lyons, hotelier Roger Saunders and P.R.

consultant Pamela McDermott. They admitted

their first black member in 1986. Despite being

one of the first of the clubs to admit women,

women still comprise a very small portion of its

the overall membership: fewer than 100 out of

1,000 members.

THE St. Botolph Club

199 Commonwealth Ave.

The St. Botolph and the Tavern are both seen as

"artistic" clubs. They are considered more

intellectual, and their purpose is to reach into those

realms beyond the mere conviviality of the clubs

down the street. Much like the Tavern, the "St. B"

brings together some of the city's leading

personalities in the fields of academia, business,

journalism and the arts. The bonhomie of the St. B

is legendary. "It is like the Signet and the Faculty

Club," says former Dean of Students Archie C.

Epps III, a former member. Since 1880, when John

C. Rope and Henry Cabot Lodge, Class of 1861,

among others, signed the charter to initiate the

club, men of the arts and letters have gathered for

the promotion of "social intercourse among

authors, artists and other gentlemen."

A poem, read at Christmas dinner in 1942, gives

some sense of who these gentlemen have

traditionally been:

Twelve hundred years ago and more

St. Botolph, Saxon to the core

With Saxon name and Saxon wit,

Moved sweetley in his floruit.

"The blueblood is no longer too visible," says

former Atlantic Monthly editor Robert Manning,

who is also a member of the Tavern.

Some of the more well-known members include

cellist Yo-Yo Ma '76, opera diva Phyllis Curtin,

Noel Stookey, the "Paul" of the folk trio Peter,

Paul and Mary, acclaimed author Ward Just and

poet Peter Davison. Every year, the club puts on

its own rendition of "Twelfth Night." The club is

home to the Litero-Culturati of Boston. Many are

art collectors. In fact, years ago, the Club used to

host a number of exhibitions. Boston's first Monet

exhibition was at the St. B.

At the turn of the century, the Women's

http://www.thecrimson.com/fmarchives/fm 04 27 2000/article11A.html

9/8/2005

Article: The Old Boys' Clubs. The Harvard Crimson Online

Page 8 of 11

Temperance Union squared off with them,

presenting petition after petition, but to no avail.

The St. B would live up to the reputation of their

namesake St. Botolph, the hard-drinking patron

saint of the Saxons. Nowadays, younger members

are setting a new example-hard liquor is no

longer a staple. Litero-Culturati and other such

cognoscenti prefer wine.

THE TAVERN CLUB

4 Boylston Place

The Tavern (1884) is said to be SO exclusive that

the man who proposed forming the club, a teacher

of Italian descent, was denied admission. Sort of.

Another story tells how a man who ate with his

toes created the club. Not quite. In fact, a group of

young artists and like-minded Gilded Age

Bostonian gentlemen would often meet together to

dine at some of the restaurants in the Park Street

area. One day a troup of vaudville freaks shoved

their way through the entrance of the restaurant

and demanded service. The "armless wonder" ate

from his plate with his toes. The founding

Taverners were appalled. One man, an Italian

teacher, proposed that they find their own room.

The group liked the idea, not him.

The Somerset was too posh and the Union too

dull, they decided, and the Tavern filled a certain

demand in the Boston social landscape. The

Tavern has always recruited members with an

inclination toward the arts, especially the

performing arts, in order to replenish the talent

pool for the yearly amateur theatrical production.

The Tavern produces an unparalleled spirit of

loyalty amongst its members.

The club's exterior is deceptively small. Inside, the

Tavern houses a theater, a billiard room, an

outdoor dining area, a big dining area and

bedrooms. Enthusiasm, hospitality and the rich

tradition of songs, remain undiminished by the

overall atmosphere of gloom and darkness.

"Incredibly pleasant," exclaims W. Shaw

McDermott '71. "I love the place! It is a great

place. There is an interesting cross-section of

people who love the exchange of ideas."

In the exclusive Tavern Club (200 members),

founded by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Class of

1861, William James, Class of 1869 and William

Dean, it is traditional to wear yellow, light blue,

purple, pink or green evening waistcoats to signify

the number of years a member has belonged to the

club. The club was founded to promote "literature,

drama and the arts." Today it more or less pursues

that mission. The club is notorious for its formerly

all-male musicals. Much like the Hasty Pudding

Theatricals, members submit plays every season

for selection and the winner is staged and

http://www.thecrimson.com/fmarchives/fm 04 27 (2000/article11A.html

9/8/2005

Article: The Old Boys' Clubs. The Harvard Crimson Online

Page 9 of 11

performed by the members. In the late '80s, the

Tavern was perhaps the most vocal opponent to

sexual integration. One production, included a

song entitled, "We love the ladies." Its final

refrain: "But we'd rather have the place in embers/

Than see them as regular members." At the time,

Globe editorial page editor H.D.S. Greenway was

quoted as saying: "There should be clubs for men,

clubs for women, and, in this case, clubs for men

who dress

up as women." But McDermott insists that the

atmosphere has not been lost with the admission of

women: "The chemistry hasn't changed much. In

fact, [sexual integration] has been a positive thing

all the way. For men and women." "The Tavern,"

says James Righter, whose wife is a member, "is

very much alive." The plays, which now include

women, "are still funny," Greenway says.

Admission to the club can be dicey for the club's

small membership. "The first criterion is that the

man be a jolly fellow," says Greenway, "you don't

have to be a captain of industry." The club that

counted John F. Kennedy '40 and Eliott

Richardson '41 among its members, now still

attract some of the most vibrant intellectuals of the

city. New York Times columnist Anthony Lewis

'48, author James Carroll, a substantial

contingency from the Globe including former

Globe publisher Benjamin O. Taylor and former

editor Tom Winship '42. There are the academics,

including Professor of Social Anthropology

emeritus Evon Vogt, Plummer Professor of

Christian Morals Peter J. Gomes, and many other

Harvard and MIT professors. The club is full of

artists, professionals, musicians, judges and the

like. Former Mass. Governor William F. Weld '66,

believing the club to be a political liability,

resigned before he ran for office.

THE CHILTON CLUB

152 Commonwealth Ave.

The city's most exclusive women's club, the

Chilton Club, was founded in 1910. Mary Chilton,

the club's namesake, was the only Mayflower

passenger to leave Plymouth and settle in Boston.

The club began in response to the Mayflower

Club, another women's club but with a strong

temperance majority. The founder of the Chilton,

Mrs. Nathaniel Thayer wanted a club where wine

and liquor would be available and where a

gentleman could be invited to dine. The women

who defected from the Mayflower were weary of

the puritanical restrictions. When the Chilton was

granted a liquor license in 1911, it was denounced

by Rev. Cortland Myers as a "pest" and the

"vestibule of Hell." "Drinking and smoking

cigarettes by women," he said, "is the most

disgusting influence in this city." The ladies

pondered legal action, but nothing came of it.

http://www.thecrimson.com/fmarchives/fm 04 27 2000/article11A.html

9/8/2005

Article: The Old Boys' Clubs. The Harvard Crimson Online

Page 10 of 11

Club historian Alexander Williams '44 recounts

the naming of what social critic Cleveland Amory

dubbed the "Female Somerset." One of the

founding ladies lamented to her husband that they

could not find a suitable name for their Puritan

alternative. "Why not the Chilton?" said the

husband. "Why the Chilton?" asked the wife.

"Because Mary Chilton was the first to leave the

Mayflower."

Before the Supreme Court ruling and the opening

of the club to men, the Chilton kept three

entryways. One front door on Commonwealth

Ave. for members only, another for the members

and their guests off to the side and a staff entrance

in back. Soon after the club opened, railroad

magnate Charles Francis Adams '32 was barred

from ever entering the club again after shoving his

way through the front entrance before declaring: "I

never use side entrances." Husbands have always

been invited.

Life at the Chilton has always been about pleasant

conversation and intellectual discourse. Lectures,

luncheons and theatre nights are the usual.

Williams describes the eccentric Eleanora Sears

during a ladies' luncheon in 1932. The subject of

the conversation was the personality of Hitler. Ms.

Sears finally lost her patience and demanded that

someone tell her who this Hitler was. The other

ladies expressed amazement that she did not know.

To this she responded indignantly, "I can't be

expected to know right off the bat the names of all

the sophomores in the Porc."

"The club is thriving," said Ms. Louisa Deland,

who joined just four years ago. "Especially now,

with the economy booming." The Chilton has

always had a continued devotion to gardening,

debutante teas, the Winter Ball and charity work

for local hospitals, museums and other cultural

institutions.

The Chilton was the last to hold out in the '80s

brouhaha over sexual integration. All set to seek

an exemption, they made a sudden about face and

admitted men, though only a handful. To date, no

blacks, Hispanics or Asians have joined. But, says

Deland, "It isn't elitist. It's just a group of like-

minded people. I don't see it as a snobby or high

brow organization."

These clubs share at least one documentable

feature in common-the era of their founding.

Somerset was founded in 1851. The Union in

1863. Beginning in the 1880s, America's most

English city saw the unleashing of a torrent of

clubs: The St. Botolph, Tavern, Algonquin,

Puritan, University, Odd Volumes, India Wharf

http://www.thecrimson.com/fmarchives/fm 04 27 2000/article11A.html

9/8/2005

Article: The Old Boys' Clubs. The Harvard Crimson Online

Page 11 of 11

Rats, Country Club (Brookline), Myopia Hunt

Club (Hamilton), Dedham Polo, Boston Athletic

(BAA), City Club Corporation, Nahant,

Mayflower (women) and Essex County. Many are

now defunct. These clubs flourished only partly

due to the town's scarcity of fine restaurants. Up

until just a couple decades ago, dinner at the

Somerset, the Algonquin or the Chilton was

considered infinitely superior to the Ritz, Locke-

Ober, Maitre Jacques or any of the other

fashionable restaurants of the time.

According to the scholar Nathan C. Shiverick '52,

the leisure bred by wealth creates a demand for an

outlet to pass the time and expend energy and

aggression. The conclusion of the Civil War

ushered in great fortunes for some Bostonians. But

Shiverick argues that more lies behind the

phenomenon. In the 1880s, when the Irish gained

municipal control of the city, the Brahmins were

politically disenfranchised. The former ruling class

of Boston reasserted itself by creating private

charitable corporations and a network of hospitals,

schools, almshouses. It was more than nobless

oblige; it was a desire to recover some control over

the city. Boston's clubs were [and still are to some

extent] the "caucus rooms of the city's financial

and charitable leaders." The Brahmin

establishment felt impelled to play some part in

local government. As they had lost control of

municipal institutions, they also lost their trust in

them. It was this distrust that led to the

incorporation of museums, orchestras and other

charitable ventures. It was this power grab that lay

behind the founding of the Museum of Fine Arts

and the Boston Public Library.

The creation of the private corporation is essential

to the structure of the clubs, says Shiverick. It

allowed for the formation of partnerships with

limited liability: each partner would not have to

risk his whole fortune if disaster struck in the case

of, say bankruptcy or lawsuits. In short, the

corporation could be used not only to finance a

railroad, but also, an orchestra, an orphanage, a

polo club equipped with an imported, famous

French chef or, as Shiverick notes, a "caucus

room." Thus, business, charitable and social

interests all merged into a giant Brahmin front at

the turn of the century. That front, moving with the

intention of regaining some control of the city,

mobilized itself in the clubrooms of Beacon Street

mansions. And the old boys' network, still

unassailable, was born.

Samuel R. Hornblower '02 is a History and

Literature concentrator in John Winthrop House

who likes to toot his own horn. He hails from Los

Angeles and will admit most anyone.

http://www.thecrimson.com/fmarchives/fn 04 27 2000/article11A.html

9/8/2005

9/9/2017

The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson - RWE.org Chapter IX Clubs The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson RWE.org

The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson RWE.org

Chapter IX Clubs

rwe.org/chapter-ix-clubs/

12/16/2004

YET Saadi loved the race of men, -

No churl, immured in cave or den;

In bower and hall

He wants them all;

But he has no companion;

Come ten, or come a million,

Good Saadi dwells alone.

Too long shut in strait and few,

Thinly dieted on dew,

I will use the world, and sift it,

To a thousand humors shift it.

CLUBS

WE are delicate machines, and require nice treatment to get from us the maximum of power and pleasure. We need tonics, but must have those

that cost little or no reaction. The flame of life burns too fast in pure oxygen, and Nature has tempered the air with nitrogen. So thought is the

native air of the mind, yet pure it is a poison to our mixed constitution, and soon burns up the bone-house of man, unless tempered with affection

and coarse practice in the material world. Varied foods, climates, beautiful objects, - and especially the alternation of a large variety of objects, -

are the necessity of this exigent system of ours. But our tonics, our luxuries, are force-pumps which exhaust the strength they pretend to supply

and of all the cordials known to us, the best, safest and most exhilarating, with the least harm, is society ; and every healthy and efficient mind

passes a large part of life in the company most easy to him.'

We seek society with very different aims, and the staple of conversation is widely unlike in its circles. Sometimes it is facts, - running from those

of daily necessity, to the last results of science, - and has all degrees of importance sometimes it is love, and makes the balm of our early and

of our latest days sometimes it is thought, as from a person who is a mind only ; sometimes a singing, as if the heart poured out all like a bird

sometimes experience. With some men it is a debate at the approach of a dispute they neigh like horses. Unless there be an argument, they

think nothing is doing. Some talkers excel in the precision with which they formulate their thoughts, so that you get from them somewhat to

remember others lay criticism asleep by a charm. Especially women use words that are not words, - as steps in a dance are not steps, - but

reproduce the genius of that they speak of; as the sound of some bells makes us think of the bell merely, whilst the church-chimes in the

distance bring the church and its serious memories before us. Opinions are accidental in people, -have a poverty-stricken air. A man valuing

himself as the organ of this or that dogma is a dull companion enough ; but opinion native to the speaker is sweet and refreshing, and

inseparable from his image. Neither do we by any means always go to people for conversation. How often to say nothing,- and yet must go ; as a

child will long for his companions, but among them plays by himself. 'T is only presence which we want. But one thing is certain, - at some rate,

intercourse we must have. The experience of retired men is positive, - that we lose our days and are barren of thought for want of some person

to talk with. The understanding can no more empty itself by its own action than can a deal box.

The clergyman walks from house to house all day all the year to give people the comfort of good talk. The physician helps them mainly in the

same way, by healthy talk giving a right tone to the patient's mind. The dinner, the walk, the fireside, all have that for their main end.'

See how Nature has secured the communication of knowledge. 'T is certain that money does not more burn in a boy's pocket than a piece of

news burns in our memory until we can tell it. And in higher activity of mind, every new perception is attended with a thrill of plea-sure, and the

imparting of it to others is also attended with pleasure. Thought is the child of the intellect, and this child is conceived with joy and born with joy.'

Conversation is the laboratory and workshop of the student. The affection or sympathy helps. The wish to speak to the want of another mind

assists to clear your own. A certain truth possesses us which we in all ways strive to utter. Every time we say a thing in conversation, we get

a

mechanical advantage in detaching it well and deliverly. I prize the mechanics of conversation. 'T is pulley and lever and screw. To fairly

disengage the mass, and send it jingling down, a good boulder, - a block of quartz and gold, to be worked up at leisure in the useful arts of life,

is a wonderful relief.

What are the best days in memory ? Those in which we met a companion who was truly such. How sweet those hours when the day was not

long enough to communicate and compare our intellectual jewels, - the favorite passages of each book, the proud anecdotes of our heroes, the

delicious verses we had hoarded ! What a motive had then our solitary days ! How the countenance of our friend still left some light after he had

9/9/2017

The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson - RWE.org Chapter IX Clubs The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson RWE.org

conversation naturally flowed, people became rapidly acquainted, and, if well adapted, more intimate in a day than if they had been neighbors for

years.

In youth, in the fury of curiosity and acquisition, the day is too short for books and' the crowd of thoughts, and we are impatient of interruption.

Later, when books tire, thought has a more languid flow : and the days come when we are alarmed, and say there are no thoughts.

What a barren-witted pate is mine the student says I will go and learn whether I have lost my reason." He seeks intelligent persons, whether

more wise or less wise than he, who give him provocation, and at once and easily the old motion begins in his brain thoughts, fancies, humors

flow the cloud lifts the horizon broadens and the infinite opulence of things is again shown him. But the right conditions must be observed.

Mainly he must have leave to be himself. Sancho Panza blessed the man who invented sleep. So I prize the good invention whereby everybody

is provided with somebody who is glad to see him.

If men are less when together than they are alone, they are also in some respects enlarged. They kindle each other and such is the power

of

suggestion that each sprightly story calls out more and sometimes a fact that had long slept in the recesses of memory hears the voice, is

welcomed to daylight, and proves of rare value. Every metaphysician must have observed, not only that no thought is alone, but that thoughts

commonly go in pairs ; though the related thoughts first appeared in his mind at long distances of time. Things are in pairs : a natural fact has

only half its value until a fact in moral nature, its counterpart, is stated.' Then they confirm and adorn each other; a story is matched by another

story. And that may be the reason why, when a gentleman has told a good thing, he immediately tells it again.

Nothing seems so cheap as the benefit of conversation nothing is more rare. 'T is wonderful how you are balked and baffled. There is plenty of

intelligence, reading, curiosity; but serious, happy discourse, avoiding personalities, dealing with results, is rare : and I seldom meet with a

reading and thoughtful person but he tells me, as if it were his exceptional mishap, that he has no companion.

Suppose such a one to go out exploring different circles in search of this wise and genial counterpart,- he might inquire far and wide.

Conversation in society is found to be on a plat-form so low as to exclude science, the saint and the poet. Amidst all the gay banter, sentiment

cannot profane itself and venture out. The re-ply of old Isocrates comes so often to mind, - The things which are now seasonable I cannot say

and for the things which I can say it is not now the time." Besides, who can resist the charm of talent ? The lover of letters loves power too.

Among the men of wit and learning, he could not withhold his homage from the gayety, grasp of memory, luck, splendor and speed such

exploits of discourse, such feats of society ! What new powers, what mines of wealth ! But when he came home, his brave sequins were dry

leaves. He found either that the fact they had thus dizened and adorned was of no value, or that he already knew all and more than all they had

told him. He could not find that he was helped by so much as one thought or principle, one solid fact, one commanding impulse : great was the

dazzle, but the gain was small. He uses his occasions he seeks the company of those who have convivial talent. But the moment they meet, to

be sure they be-gin to be something else than they were ; they play pranks, dance jigs, run on each other, pun, tell stories, try many fantastic

tricks, under some superstition that there must be excitement and elevation :- and they kill conversation at once. I know well the rusticity of the

shy hermit. No doubt he does not make allowance enough for men of more active blood and habit. But it is only on natural ground that

conversation can be rich. It must not begin with uproar and violence. Let it keep the ground, let it feel the connection with the battery. Men must

not be off their centres.

Some men love only to talk where they are masters. They like to go to school-girls, or to boys, or into the shops where the sauntering people

gladly lend an ear to any one. On these terms they give information and please them-selves by sallies and chat which are admired by the idlers

and the talker is at his ease and jolly, for he can walk out without ceremony when he pleases. They go rarely to their equals, and then as for

their

own convenience simply, making too much haste to introduce and impart their new whim or discovery listen badly or do not listen to the

comment or to the thought by which the company strive to repay them rather, as soon as their own speech is done, they take their hats. Then

there are the gladiators, to whom it is always a battle; 't is no matter on which side, they fight for victory; then the heady men, the egotists, the

monotones, the steriles and the impracticables.

It does not help that you find as good or a better man than yourself, if he is not timed and fitted to you. The greatest sufferers are often those who

have the most to say, - men of a delicate sympathy, who are dumb in mixed company. Able people, if they do not know how to make allowance

for them, paralyze them. One of those conceited prigs who value Nature only as it feeds and exhibits them is equally a pest with the roysterers.

There must be large reception as well as giving. How delightful after these disturbers is the radiant, playful wit of - one whom I need not name,

-

for in every society there is his representative. Good nature is stronger than tomahawks. His conversation is all pictures he can reproduce

whatever he has seen he tells the best story in the county, and is of such genial temper that he disposes all others irresistibly to good humor

and discourse. Diderot said of the Abbe Galiani: He was a treasure in rainy days and if the cabinet-makers made such things, everybody

would have one in the country."

One lesson we learn early, - that in spite of seeming difference, men are all of one pattern. We readily assume this with our mates, and are

disappointed and angry if we find that we are premature, and that their watches are slower than ours. In fact the only sin which we never forgive

in each other is difference of opinion. We know beforehand that yonder man must think as we do. Has he not two hands, - two feet, - hair and

nails ? Does he not eat, - bleed, - laugh, - cry ? His dissent from me is the veriest affectation. This conclusion is at once the logic of persecution

and of love. And the ground of our indignation is our conviction that his dissent is some wilfulness he practises on himself. He checks the flow of

his opinion, as the cross cow holds up her milk. Yes, and we look into his eye, and see that he knows it and hides his eye from ours.

But to come a little nearer to my mark, I am to say that there may easily be obstacles in the way of finding the pure article we are in search of,

but when we find it it is worth the pursuit, for beside its comfort as medicine and cordial, once in the right company, new and vast values do not

fail to appear. All that man can do for man is to be found in that market. There are great prizes in this game. Our fortunes in the world are as our

mental equipment for this competition is. Yonder is a man who can answer the questions which I cannot. Is it so? Hence comes to me boundless

curiosity to know his experiences and his wit. Hence competition for the stakes dearest to man. What is a match at whist, or draughts, or

billiards. or chess. to a match of mother-wit of knowledge and of re-sources? However courteously we conceal it. it is social rank and spiritual

9/9/2017

The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson - RWE.org Chapter IX Clubs The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson RWE.org

He that can define, he that can answer a question so as to admit of no further answer, is the best man. This was the meaning of the story of the

Sphinx. In the old time conundrums were sent from king to king by ambassadors. The seven wise masters at Periander's banquet spent their

time in answering them. The life of Socrates is a propounding and a solution of these. So, in the hagiology of each nation, the lawgiver was in

each case some man of eloquent tongue, whose sympathy brought him face to face with the extremes of society. Jesus, Menu, the first

Buddhist, Mahomet, Zertusht, 1 Pythagoras, are examples.

Jesus spent his life in discoursing with humble people on life and duty, in giving wise answers, showing that he saw at a larger angle of vision,

and at least silencing those who were not generous enough to accept his thoughts. Luther spent his life so and it is not his theologic works,

-

his Commentary on the Galatians, and the rest, but his Table-Talk, which is still read by men. Dr. Johnson was a man of no profound mind, - full

of English limitations, English politics, English Church, Oxford philosophy yet, having a large heart, mother-wit and good sense which

impatiently overleaped his customary bounds, his conversation as re-ported by Boswell has a lasting charm. Conversation is the vent of

character as well as of thought and Dr. Johnson impresses his company, not only by the point of the remark, but also, when the point fails,

because he makes it. His obvious religion or superstition, his deep wish that they should think so or so, weighs with them, so rare is depth of

feeling, or a constitutional value for a thought or opinion, among the light-minded men and women who make up society ; and though they know

that there is in the speaker a degree of shortcoming, of insincerity and of talking for victory, yet the existence of character, and habitual reverence

for principles over talent or learning, is felt by the frivolous.

One of the best records of the great German master who towered over all his contemporaries in the first thirty years of this century, is his

conversations as recorded by Eckermann and the Table-Talk of Coleridge is one of the best remains of his genius.

In the Norse legends, the gods of Valhalla, when they meet the Jotuns, converse on the perilous terms that he who cannot answer the other's

questions forfeits his own life. Odin comes to the threshold of the Jotun Wafthrudnir in disguise, calling himself Gangrader; is invited into the hall,

and told that he cannot go out thence unless he can answer every question Wafthrudnir shall put. Wafthrudnir asks him the name of the god of

the sun, and of the god who brings the night what river separates the dwellings of the sons of the giants from those of the gods ; what plain lies

between the gods and Surtur, their adversary, etc. ; all which the disguised Odin answers satisfactorily. Then it is his turn to interrogate, and he is

answered well for a time by the Jotun. At last he puts a question which none but himself could answer:

What did Odin whisper in the ear of his son Balder, when Balder mounted the funeral pile ?" The startled giant replies: None of the gods knows

what in the old time THOU saidst in the ear of thy son : with death on my mouth have I spoken the fate-words of the generation of the Aesir; with

Odin contended I in wise words. Thou must ever the wisest be."

And still the gods and giants are so known, and still they play the same game in all the million mansions of heaven and of earth at all tables,

clubs and tete-a-tetes, the lawyers in the court-house, the senators in the capitol, the doctors in the academy, the wits in the hotel. Best is he

who gives an answer that cannot be answered again. Omnis definitio periculosa est, and only wit has the secret. The same thing took place

when Leibnitz came to visit Newton; when Schiller came to Goethe ; when France, in the person of Madame de Stael, visited Goethe and

Schiller; when Hegel was the guest of Victor Cousin in Paris when Linnaeus was the guest of Jussieu. It happened many years ago that an

American chemist carried a letter of introduction to Dr. Dalton of Manchester, England, the author of the theory of atomic proportions, and was

coolly enough received by the doctor in the laboratory where he was engaged. Only Dr. Dalton scratched a formula on a scrap of paper and

pushed it towards the guest,-" Had he seen that ? The visitor scratched on another paper a formula describing some results of his own with

sulphuric acid, and pushed it across the table, -" Had he seen that ? The attention of the English chemist was instantly arrested, and they

became rapidly acquainted.

To answer a question so as to admit of no reply, is the test of a man, - to touch bottom every time. Hyde, Earl of Rochester, asked Lord-Keeper

Guilford, " Do you not think I could understand any business in England in a month ? Yes, my lord," replied the other, but I think you

would

understand it better in two months." When Edward I. claimed to be acknowledged by the Scotch (1292) as lord paramount, the nobles of

Scotland replied, No answer can be made while the throne is vacant." When Henry III. (1217) plead duress against his people demanding

confirmation and execution of the Charter, the reply was If this were admitted, civil wars could never close but by the extirpation of one of the

contending parties."

What can you do with one of these sharp respondents ? What can you do with an eloquent man ? No rules of debate, no contempt of court, no

exclusions, no gag-laws can be contrived that his first syllable will not set aside or overstep and annul. You can shut out the light, it may be, but

can you shut out gravitation ? You may condemn his book, but can you fight against his thought? That is always too nimble for you, anticipates

you, and breaks out victorious in some other quarter. Can you stop the motions of good sense ? What can you do with Beaumarchais, who

converts the censor whom the court has appointed to stifle his play into an ardent advocate ? The court appoints another censor, who shall crush

it

this time. Beaumarchais persuades him to defend it. The court successively appoints three more severe inquisitors; Beaumarchais converts

them all into triumphant vindicators of the play which is to bring in the Revolution." Who can stop the mouth of Luther, - of Newton, - of Franklin,

- of Mirabeau, - of Talleyrand

These masters can make good their own place, and need no patron. Every variety of gift - science, religion, politics, letters, art, prudence, war or

love - has its vent and exchange in conversation. Conversation is the Olympic games whither every superior gift resorts to assert and approve

itself, - and, of course, the inspirations of powerful and public men, with the rest. But it is not this class, whom the splendor of their

accomplishment almost inevitably guides into the vortex of ambition, makes them chancellors and commanders of council and of action, and

makes them at last fatalists, - not these whom we now consider. We consider those who are interested in thoughts, their own and other men's,

and who delight in comparing them who think it the highest compliment they can pay a man to deal with him as an intellect, to expose to him

the grand and cheerful secrets perhaps never opened to their daily companions, to share with him the sphere of freedom and the simplicity of

truth.'

9/9/2017

The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson - RWE.org Chapter IX Clubs The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson RWE.org

It is possible that the best conversation is between two persons who can talk only to each other. Even Montesquieu confessed that in

conversation, if he perceived he was listened to by a third person, it seemed to him from that moment the whole question vanished from his

mind. I have known persons of rare ability who were heavy company to good social men who knew well enough how to draw out others of

retiring habit and, moreover, were heavy to intellectual men who ought to have known them. And does it never occur that we perhaps live with

people too superior to be seen, - as there are musical notes too high for the scale of most ears ? There are men who are great only to one or

two companions of more opportunity, or more adapted.

It was to meet these wants that in all civil nations attempts have been made to organize conversation by bringing together cultivated people

under the most favorable conditions. 'T is certain there was liberal and refined conversation in the Greek, in the Roman and in the Middle Age.

There was a time when in France a revolution occurred in domestic architecture; when the houses of the nobility, which, up to that time, had

been constructed on feudal necessities, in a hollow square,- the ground-floor being resigned to offices and stables, and the floors above to

rooms of state and to lodging-rooms, were rebuilt with new purpose. It was the Marchioness of Rambouillet who first got the horses out of and

the scholars into the palaces, having constructed her hotel with a view to society, with superb suites of drawing-rooms on the same floor, and

broke through the morgue of etiquette by inviting to her house men of wit and learning as well as men of rank, and piqued the emulation of

Cardinal Richelieu to rival assemblies, and so to the founding of the French Academy. The history of the Hotel Rambouillet and its brilliant circles

makes an important date in French civilization. And a history of clubs from early antiquity, tracing the efforts to secure liberal and refined

conversation, through the Greek and Roman to the Middle Age, and thence down through French, English and German memoirs, tracing the

clubs and coteries in each country, would be an important chapter in history. We know well the Mermaid Club, in London, of Shakspeare, Ben

Jonson, Chapman, Herrick, Selden, Beaumont and Fletcher its Rules are preserved, and many allusions to their suppers are found in Jonson,

Herrick and in Aubrey. Anthony Wood has many details of Harrington's Club. Dr. Bentley's Club held Newton, Wren, Evelyn and Locke and we

owe to Boswell our knowledge of the club of Dr. Johnson, Goldsmith, Burke, Gibbon, Reynolds, Garrick, Beauclerk and Percy. And we have

records of the brilliant society that Edinburgh boasted in the first decade of this century. Such societies are possible only in great cities, and are

the compensation which these can make to their dwellers for depriving them of the free intercourse with Nature. Every scholar is surrounded by

wiser men than he - if they cannot write as well.' Cannot they meet and exchange results to their mutual benefit and delight ? It was a pathetic

experience when a genial and accomplished person said to me, looking from his country home to the capital of New England, " There is a town

of two hundred thousand people, and not a chair in it for me." If he were sure to find at No. 2000 Tremont Street what scholars were abroad after

the morning studies were ended, Boston would shine as the New Jerusalem to his eyes.

Now this want of adapted society is mutual. The man of thought, the man of letters, the man of science, the administrator skilful in affairs, the

man of manners and culture, whom you so much wish to find, - each of these is wishing to be found. Each wishes to open his thought, his

knowledge, his social skill to the daylight in your company and affection, and to exchange his gifts for yours ; and the first hint of a select and

intelligent company is welcome.

But the club must be self-protecting, and obstacles arise at the outset. There are people who cannot well be cultivated; whom you must keep

down and quiet if you can. There are those who have the instinct of a bat to fly against any lighted candle and put it out, - marplots and

contradictors. There are those who go only to talk, and those who go only to hear both are bad. A right rule for a club would be, - Admit no man

whose presence excludes any one topic. It requires people who are not surprised and shocked, who do and let do and let be, who sink trifles and

know solid values, and who take a great deal for granted.

is always a practical difficulty with clubs to regulate the laws of election §0 as to exclude peremptorily every social nuisance. Nobody wishes

bad manners. We must have loyalty and character. The poet Marvell was wont to say that he would not drink wine with any one with whom

he

could not trust his life." But neither can we afford to be superfine. A man of irreproachable behavior and excellent sense preferred on his travels

taking his chance at a hotel for company, to the charging himself with too many select letters of introduction. He confessed he liked low

company. He said the fact was incontestable that the society of gypsies was more attractive than that of bishops. The girl deserts the parlor for

the kitchen the boy, for the wharf. Tutors and parents cannot interest him like the uproarious conversation he finds in the market or the dock. I

knew a scholar, of some experience in camps, who said that he liked, in a barroom, to tell a few coon stories and put himself on a good footing

with the company : then he could be as silent as he chose. A scholar does not wish to be always pumping his brains he wants gossips. The

black-coats are good company only for black-coats but when the manufacturers, merchants and shipmasters meet, see how much they have to

say, and how long the conversation lasts ! They have come from many zones ; they have traversed wide countries ; they know each his own arts,

and the cunning artisans of his craft they have seen the best and the worst of men. Their knowledge contradicts the popular opinion and your

own on many points. Things which you fancy wrong they know to be right and profitable things which you reckon superstitious they know to be

true. They have found virtue in the strangest homes and in the rich store of their adventures are instances and examples which you have been

seeking in vain for years, and which they suddenly and unwittingly offer you.

I

remember a social experiment in this direction, wherein it appeared that each of the members fancied he was in need of society, but himself

unpresentable. On trial they all found that they could be tolerated by, and could tolerate, each other. Nay, the tendency to extreme self-respect

which hesitated to join in a club was running rapidly down to abject admiration of each other, when the club was broken up by new combinations.

The use of the hospitality of the club hardly needs explanation. Men are unbent and social at table and I remember it was explained to me, in a

Southern city, that it was impossible to set any public charity on foot unless through a tavern dinner. I do not think our metropolitan charities

would plead the same necessity but to a club met for conversation a supper is a good basis, as it disarms all parties and puts pedantry and

business to the door. All are in good humor and at leisure, which are the first conditions of discourse the ordinary reserves are thrown off,

experienced men meet with the freedom of boys, and, sooner or later, impart all that is singular in their experience.

The

hospitalities

of

clubs

are

easily

doubt

the

sunners

of

wits

and

philosonhers

acquire

much

lustre

by

time

and

9/9/2017

The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson - RWE.org Chapter IX Clubs - The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson RWE.org

When we such clusters had

As made us nobly wild, not mad;

And yet, each verse of thine

Outdid the meat, outdid the frolic wine."

,

Such friends make the feast satisfying; and I notice that it was when things went prosperously, and the company was full of honor, at the banquet

of the Cid, that " the guests all were joyful, and agreed in one thing, - that they had not eaten better for three years."

I need only hint the value of the club for bringing masters in their several arts to compare and expand their views, to come to an under-standing

on these points, and so that their united opinion shall have its just influence on public questions of education and politics. It is agreed that in the

sections of the British Association more information is mutually and effectually communicated, in a few hours, than in many months of ordinary

correspondence and the printing and transmission of ponderous reports. We know that 1' homme de lettres is a little wary, and not fond of giving

away his seed-corn ; but there is an infallible way to draw him out, namely, by having as good as he. If you have Tuscaroora and he Canada, he

may exchange kernel for kernel. If his discretion is incurable, and he dare not speak of fairy gold, he will yet tell what new books he has found,

what old ones recovered, what men write and read abroad. A principal purpose also is the hospitality of the club, as a means of receiving a

worthy foreigner with mutual advantage.

Every man brings into society some partial thought and local culture. We need range and alternation of topics and variety of minds. One likes in a

companion a phlegm which it is a triumph to disturb, and, not less, to make in an old acquaintance unexpected discoveries of scope and power

through the advantage of an inspiring subject. Wisdom is like electricity. There is no permanently wise man, but men capable of wisdom, who,

being put into certain company, or other favorable conditions, become wise for a short time, as glasses rubbed acquire electric power for a

while. 1 But while we look complacently at these obvious pleasures and values of good companions, I do not forget that Nature is always very

much in earnest, and that her great gifts have something serious and stern. When we look for the highest benefits of conversation, the Spartan

rule of one to one is usually enforced. Discourse, when it rises high-est and searches deepest, when it lifts us into that mood out of which

thoughts come that remain as stars in our firmament, is between two.'

BEACON

HILL

Mount Vernon Street

&

Beacon Street

BACK

SAY

4

S

2

3

Commonwealth Avenue

7

Click to enlarge. (Photographs by Toan Trinh)

1. The Harvard Club of Boston

374 Commonwealth Ave.

Founded: 1908

Details: Open to Harvard alums, employees, and their relatives, the club does offer entry to anyone

(sans a Harvard degree) willing to drop up to $6 million on one of its new condos, built to finance a

recent renovation.

xfinity

Xfinity

Sponsored

Get up to speed

xfinity

with Xfinity Internet.

xfinity

xFr

Most Active Profiles

:

The

Simple. Easy. Awesome.

Members Only: Boston's Private Social Clubs

Page 3 of 9

Classic moment: Dick Cheney had to sneak in through the back door for a speaking engagement in

2006 due to the throngs of protesters.

2. The Algonquin Club

217 Commonwealth Ave.

Founded: 1888

Details: Like Fight Club, if you're in Algonquin, you don't talk about Algonquin. Word is the

mortgage was burned long ago and its ashes were placed in a tiny box next to the main fireplace in

the reading room.

Presidential power: Calvin Coolidge.

Pretend power: Clark Rockefeller.

3. St. Botolph Club

199 Commonwealth Ave.

Founded: 1880

Details: Founded for black-sheep bluebloods (those moody creative types), the club's foundation

gives away approximately $75,000 a year in grants to young New England musicians, painters, poets,

and writers.

Artistic bona fides: The roster includes John Quincy Adams, John Singer Sargent, and Robert

Frost.

4. The College Club of Boston

44 Commonwealth Ave.

Founded: 1890

Details: Once a haven for well-bred Wellesley and Smith grads, this elaborate brownstone now

serves as a hub for the Lean In crowd.

Male presence: Literary visitors have included Mark Twain and Vladimir Nabokov.

5. Somerset Club

42 Beacon St.

Founded: 1852

https://www.bostonmagazine.com/news/2015/04/28/boston-private-social-clubs/

2/18/2020

Members Only: Boston's Private Social Clubs

Page 4 of 9

Details: The stone wall with security detail out front underscores this club's rep as the snootiest of

the bunch. When a fire broke out in the kitchen in the 1940s, firemen had to enter through the

servants' entrance to avoid disrupting the ladies and gents lunching in the dining room.

Notable guests: Nathaniel Hawthorne and Theodore Roosevelt have graced the Somerset's

hallowed halls.

6. Club of Odd Volumes

77 Mount Vernon St.

Founded: 1887

Details: Think: bibliophiles, books, and bow ties. "They are the epitome of the stereotypical old-

world, elegant, intellectually curious Bostonians," says one club visitor. The interior is like a time

machine: An ancient black rotary telephone still adorns the coat room.

Making history: Winston Churchill stopped by for a visit in 1949.

7. Union Club of Boston

8 Park St.

Founded: 1863

Details: During the Civil War, members of the Somerset Club split along political lines. In response,

Somerset defectors formed the Union Club, which demanded "unqualified loyalty to the constitution

and the Union of our United States, and unwavering support of the Federal Government in effort for

the suppression of the rebellion."

Lineage: Past members include Ralph Waldo Emerson and Josiah Quincy.

You Might Also Like

Boston Picnic Guide: Where to

Order, and Where to Eat

https://www.bostonmagazine.com/news/2015/04/28/boston-private-social-clubs/

2/18/2020

ABIGAIL, the Library Catalog of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Page 1 of 2

Massachusetts

Historical Society

ABIGAIL

Founded

1791

the Library Catalog of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Search

Hearlings

Titles

History

Help

ABIGAIL Home

Database Name: Massachusetts Historical Society

Search Request: Keyword Anywhere = clubs. massachusetts. boston

Search Results: Displaying 3 of 100003 entries

Previous Next

Bibliographic

Holdings

Table of Contents

MARC View

The clubs of Boston : containing a complete list of members and

addresses.

Relevance:

Format:

Book

Call number(s):

HS2725.B6 A1 1891

Place Request

Title: