From collection Creating Acadia National Park: The George B. Dorr Research Archive of Ronald H. Epp

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

Page 62

Search

results in pages

Metadata

[Series III] Biological Themes

Biological Themes

explore Bar

Old Farm,

Garbor, Maine.

long Merbarium

Cambridge Mals

Dear his

Can you identify

for My I Ifours it flowing i my

plant Murlines here, a Single, plant of

it The Color of H. flower in a bright

ries blue quits beautiful at John it part is him not

a nature plant but Our obtained for

the Mursines to by, whom have be got

lost The lucloud price is Mlfull

hugst of rh plant Itwa in flower

18 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston

July 1st, 1902.

Curator Gray Herbarium,

Cambridge, Mass.

For

study

Written

be

obtei

Dear Sir,

In reply to the circular sent me this spring and which

I now seem to have mislaid I enclose you my check for $10.

towards the maintenance of the Herbarium,

I also wish to ask you whether there is any book or pub-

lication which I can obtain which would aid me in studying the

flora and forest growth of Arizona and Utah, and similarly of

Oregon, Washington and the Canadian Rockies. I am just

starting West for Colorado, to most Professor Davis in southern

Utah. and join him in an expedition down the western side of

the Grand Cañon where I shall be for some weeks. And later

I shall probably go un by way of Oregon and Washington and

spend a few weeks camping out either there or among the Cana-

dian Rockies, and any book, not too bulky to carry, which would

help me to identify the plant life in either of those regions

I should be glad to know of. What is the best way, also, of

preserving the flowers and leaves of plants for later study and

identification when one is on a camping trip where weight is

of importance and space valuable.

As I leave for the West in the middle of the day tomorrow

3 page 1

2

I should be glad if you could let me have some word in reply,

if you can conveniently do so, by this evening's mail 80 that

I might receive it in the morning. If not,will you kindly

write to me to await me at the post office at Provo City, Utah,

where I shall be about the 10th of this month, and oblige

greatly

Yours truly,

GRAY HEREARIUM

ARCH V.E.S

For study

Written author casion must be

18 Commonwealth Avenue.

obtai ed for cil other uses

April 24th, 1905.

Dear Mr Robinson,

Please excuse an invitation by typewriter, but I

have got to go down to Bar Harbor tonight to look after the

spring planting at my Nurseries.

I am going to have some colored lantern slides of the

Canadian Rocky wild-flowers, shown at the Tavern Club on Monday

evening, May first, after its annual meeting. And I am

allowed to ask in a few guests of my own to see them. If you

will be one of these and will come at quarter past nine to

the Club house in Boylston Place, it will give me great pleasure

to welcome you there. The coloring of the flowers has been

unusually well done, from notes taken when the flowers them-

selves were photographed, and the slides, which are not my own,

of course, give one a really good idea, I think, of the flowers

and plants themselves as one sees them growing in the mountains.

Hoping you may come, I am

Dea the Robinson

Sincerely yours,

The Slide an the Cleaner's

for have diew intent Ging. B. wass

my Sum

you And if their should he any The item the will Department

If that I think they would in

when you think Height also like Where y not

Benjamin L. Robinson,

Esq. please efficial my auritation

him also this him wilt yr GBW- Z

18 Commonwealth Avenue.

Boston, June 9th, 1905.

Gray Herbarian,

Harvard University, Cambridge.

Dear Sir,

will you kindly write me on the enclosed postal

the name of this flower which I came upon growing freely

upon the banks of the Charles river out at Wellesley yester-

day ?

It is one familiar to me but I cannot recall its

name.

Yours truly,

George B. Dorr.

Per M.Z.H.

18 Commonwealth Avenue

Boston, June 16th, 1905.

Gray Herbarian,

Harvard University,

Cambridge. Mass.

Dear Sir,

Can you tell me what the enclosed plant is which I

found at day or two ago growing on a shady bank in Lenox ?

It

covered the ground where it was growing with its leaves but it

was not in flower. I enclose addressed postal for reply,

and am

Yours very truly,

George 3. Doer.

Per M.E.H.

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

LAFAYETTE NATIONAL PARK

BAR HARBOR, MAINE

OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT

May 18, 1926.

Professor II. L. Fernald,

Gray Herbarium,

Harvard University,

Cambridge, Mass.

Dear Professor Fernald:

I have just returned to Bar Harbor

and found your kind enclosure of two publications

telling of the Gray Herbarium Expedition to Nova

Scotia and of the persistence of plants in un-

glaciated areas.

Accept my most cordial thanks and

believe me

Yours sincerely,

EL-O

George R. Wor

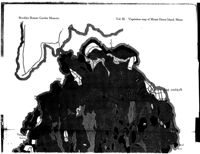

BROOKLYN BOTANIC GARDEN

MEMOIRS

VOLUME III.

VEGETATION OF MOUNT DESERT ISLAND, MAINE,

AND ITS ENVIRONMENT

By

BARRINGTON MOORE and NORMAN TAYLOR

ISSUED JUNE 10, 1927

BROOKLYN, N. Y., U. S. A.

Maine

Prettymar

Harbor

Pretty

marsh

Harbor

Great

Head

offer Creek Point

Seal

SEal

Harbo

KEY

Southwest Harbor

SPRUCE

CEDAR

MIXED

CONIFER

BURNS

FIR

MARSH

PITCH PINE

BOG

HARDWOODS

ROCK

Base

Harbor

NORTHERN

Bennet Cove

o

2

HARDWOODS-

WHITE PINE

4

SPRUCE

SCALE OF MILES

PLATE I.

Vegetation map of Mt. Desert Island, showing the forest types, bare rock, marshes and bogs. The larger open fields are shown in white.

The

selected for study of environmental factors are shown as follows: 1=Pitch Pine on Huguenot Head; 2=White Pine at Bear Brook Hill; 3=Red Oak

sites

and 4=Spruce at Otter Creek Point.

at

Meadow

Brook;

0

CONTENTS

Page

Location

I

Land Forms

3

Geology

5

Soil

12

Post-Glacial Migration of Vegetation

14

History

17

General Character of the Present Vegetation

25

Distributional Relations

25

Forest Types

28

The Environment

32

General Climate of Mount Desert Island

32

Precipitation

33

Temperature

34

Growing Season

35

Environmental Factors in Representative Forest Types

35

Selection of Stations in Four Representative Forest Types

36

The Forests

37

Pitch Pine

37

White Pine

40

Red Oak

43

Spruce

45

The Soils

47

Instrumental Records of Climatic Factors

58

Factors Measured

58

Results

62

General

62

Evaporation

62

Solar Radiation

70

Soil Temperature

73

Interpretation

78

Developmental Trends of Vegetation

85

Rock Ledges and Talus Slopes

88

The Advent of Higher Woody Vegetation

94

Pioneer Plant Associations on Soil

97

The Pitch Pine

100

Scrub Oak on Acadia (Robinson) Mountain

104

Summary of Pitch Pine

III

White Pine

III

Mixed Conifer

114

Fire and What Follows

118

The Hardwoods

122

Spruce Climax Forest

124

Northern Hardwoods-Spruce Climax Forest

127

The Rôle of Certain Mt. Desert Plants in the Development of the Vegetation. 128

Stages Originating in Water

131

Poor Drainage-Bogs

132

Good Drainage-Cedar Swamps

137

Practical Considerations in Forestry

140

Summary

143

Literature Cited

149

iii

HISTORY

Because the actions of man, red and white. since the occupation of the

island, have materially affected its vegetation, we could wish that the record

were more complete. How long the Indians lived on the island before the

white man came, we have no means of knowing. But it is evident that with

their crude culture and stone implements they would be able to effect less

change in a thousand years than the white man could in ten. The Indians

had, nevertheless, one means of destruction in common with the white man-

fire. We know that in hunting they sometimes set fires in order to drive out

the game (Street, 1905, p. 60). This seems to have been a common practice

among all Indians who depended largely or wholly on hunting. Yet there

were still vast stretches of magnificent timber when the white man came.

Possibly the fires were comparatively small. It is also more than probable

that the fires burned with less fierceness before the forests were cut. The

destructive fires of today which SO frequently follow logging operations often

start in the fallen tops and other debris. Furthermore, an untouched forest

along the Maine Coast, with its deep carpet of moss, is much less inflammable

than the same forest would be after some of the trees had been cut and the

light which is thus let in had partly dried out the forest floor.

The earliest record was. fortunately. made by Champlain (1613) in his

account of the voyage on which he discovered the island. He writes under

date of September 5, 1604:

The same day we passed near to an island some four or five leagues long,

in the neighborhood of which we just escaped being lost on a rock that was

just awash and which made a hole in the bottom of our boat. From this

island to the mainland on the north the distance is not more than a hundred

paces. The island is high and notched in places SO that from the sea it gives

the appearance of a range of seven or eight mountains. The summits are

all bare and rocky. The slopes are covered with pines, firs. and birches. I

named it Isle des Monts Desert."

It thus appears that the island was covered almost completely with forest,

except for the bare granite summits. From what we know of the virgin

forest of the region we can picture to ourselves what Champlain probably

saw. The 'firs which he speaks of must have been balsam fir and spruce,

both red and white. which probably formed a more or less uniform canopy

17

18

BROOKLYN BOTANIC GARDEN MEMOIRS

above which towered here and there giant white pines. The birches indi-

cate past fires, since in very old forests they are crowded out, or reduced to

inconspicuous scattered individuals, by the conifers.

The bare rock of the summits, though conspicuous, was less in evidence

than it is today. The white man has extended the area of the barren places

by fire and cutting.

Fortunately, we possess a second account of the island written by a

French friar only nine years after Champlain's visit. The expedition under

de la Saussaye, sent out by Mme. de Guercheville, was caught in a fog on its

way from the new settlement at Port Royal (in what is now Nova Scotia)

to its intended destination up the Penobscot River to the present site of Bangor.

When the fog lifted they found themselves off Mt. Desert Island at a point

which is supposed to be the present site of Bar Harbor, or Hull's Cove, and

which they called St. Sauveur, a name which they later transferred to their

short-lived settlement at the mouth of Somes Sound. Father Biard (Saw-

telle, 1921) thus describes what he saw :

'There in all the glory that spring imparts to hillside and valley lay the

island of the Desert Mountains, its tall pines and pointed firs, mingling with

birches, whose lighter shades made marked contrast with the darker ever-

green; while barren summits, catching the rays of the hidden sun, gleamed

like hammered brass." The italics are ours.

The picture agrees with that described by Champlain. There were also

other types of forest which, since they were not on the slopes, were not visible

from the sea. In the valleys and lower slopes on both sides of Pemetic there

must have been bodies of beech, yellow birch and sugar maple with an admix-

ture of red spruce, and probably also an occasional giant white pine. A

remnant of this forest, without the pine. may be seen today just south of

Eagle Lake along the carry trail to Jordan Pond. In certain of the swamps

there were stands of nearly pure white cedar or arbor vitae, some of the

trees of large size. Probably cedar also grew scattered throughout the rest

of the forest as it does today. There must also have been groups of pitch

pine, though probably less than now, and scattered red or Norway pine.

There may also have been stands with considerable quantities of red oak. if

the names such as Oak Hill, and some of the present forests, are reliable

indications.

From 1613. when the English under Captain Argall destroyed the pre-

carious French foothold at Somes Sound. the island appears to have been

practically uninhabited by white men for about a hundred and fifty years.

In 1689 the island was granted to Sieur de la Mothe Cadillac by Louis XIV.

E. IRENE GRAVES

VEGETATION OF MOUNT DESERT ISLAND, MAINE

19

and from the Andros census (Hutchinson Papers) we are led to assume

that Cadillac and his wife were living on the island in 1688, though his stay

must have been brief since he was in France in 1689. In his account of the

island, Cadillac says Good masts may be got here and the English formerly

used to come here for them." Therefore, although the island was not in-

habited by white men, it was occasionally visited, and some of its trees were

cut. These were probably only a comparatively small number of selected

spruces and white pines, the removal of which had practically no effect on

the forest.

The annals of the first permanent settlers begin after 1762, which may

be taken as the starting point for the white man's influence on the vegetation.

Probably white men started living on the island some years before this, but

we have no records showing when or how many there were. The early

settlers appear to have depended to a large extent on the wild grass of the

marshes for hay to feed their stock. This wild hay seems to have been

useful not only to the dwellers on the island itself but to those of the adjacent

mainland. if we may judge by a petition sent by the islanders to Governor

Bernard in 1768 complaining against these raids or "In Crossins" of the

mainland settlers which threatened the stock on the island with starvation.

The value of the forests was recognized from the beginning. The same

petition seeks protection from mainland trespassers who cut timber as well

as from those seeking hay. It is stated that this cutting of the timber, which

includes staves, shingles. clapboards and other lumber," will "discourage

future settlers." It is evident that the earliest comers depended largely on

the plant resources which nature had grown on the island through the long

period of years when it was unoccupied, and then used only by the Indians

for hunting.

The wild hay gave food for the stock. and thus indirectly to its owners.

But no doubt the main reliance was the crops raised on the more level and

promising bits of land which had to be cleared. The proportion of level land

on the island is not great. and that which is fertile is smaller still. Thus the

food which can be produced will support only a comparatively small popula-

tion. The fisheries comprised an important means of livelihood, and largely

supported the small villages along the shore. But the main wealth of the

island lay in its forests, as it still does. if we except that brought in by summer

visitors.

It is not difficult to picture to ourselves the kind of cuttings which took

place from the early settlements to the present time. There were none of

the usual large operations by which extensive areas are stripped to feed a

big mill which cuts and ships vast quantities of lumber and is then abandoned

20

BROOKLYN BOTANIC GARDEN MEMOIRS

when the surrounding territory is 'cut out." Fortunately, the coast

of

Maine, as well as the rest of the state, largely escaped the "boom" type of

development which makes flourishing lumbering towns for a decade or two

and passes on leaving a virtual desert behind, as in Pennsylvania, the Lake

States and now the Southern pineries.

On Mt. Desert Island the lumbering was never, happily for the island, on

a scale comparable with that in Pennsylvania, or even in other parts of Maine.

At first it was probably largely for local consumption, and the logs were cut

at small mills run by water power. Later, the operations seem to have in-

creased in size, and much or most of the lumber was doubtless shipped out

of the island. By 1870 there were two steam sawmills, one at Salisbury

Cove and the other at Pretty Marsh, and ten water sawmills (Street, 1905,

p. 309) This may not represent the maximum of the island's lumber pro-

duction, which perhaps came some time earlier. Whatever the amounts cut

from year to year, it is certain that the island has been steadily producing

more or less lumber from the time it was first settled to the present day.

Although there has been no attempt to exercise forethought, the size of the

cuttings has been small enough not to take all the mature growth before the

second growth was ready to use. The greatest destruction has been from

fire, which has swept over a large part of the island thus materially reducing

the available stock of growing timber. The effect of these fires on the vege-

tation will be dealt with more fully in another place.

In the earlier cuttings. in fact until rather recently, the forests were not

cut clean because the demand for the products was limited. At first they

were skimmed of the very large white pine which commanded a ready and

profitable market both in this country and over seas. These trees were found

as scattered individuals throughout the forest, or in small groups. There

may also have been here and there nearly pure stands of white pine, or at

least stands in which a large proportion of the volume was white pine.

A

remnant of such a stand has been fortunately preserved around Fawn Pond.

Here the bulk of the forest is made up of very large old white pine trees

such as must have been common over the island when Champlain sailed past.

The removal of the scattered pines made only rather small holes in the forest

canopy, which soon closed up leaving a uniform cover of spruce and fir.

Under this cover there could be little reproduction of white pine because of

the shade. It could seed in only where the cuttings made openings large

enough to let in the sunlight. or where several large spruces happened to be

blown down by the wind or died from other causes.

The cutting of these large trees must have begun soon after the island was

settled. The more accessible ones were of course taken first. Just how long

VEGETATION OF MOUNT DESERT ISLAND. MAINE

21

st of

it continued we do not know, but probably before the middle of the nineteenth

ype of

century only those large pines on the steeper and more difficult slopes were

r two

left. The remnants we have today happen to be on property from which the

Lake

owners for some reason or other did not sell the timber.

The next phase consisted of going through the same forests in order to

nd, on

take out the larger and finer spruces for sawing into lumber of various kinds.

Maine.

Some of the larger spruce trees were doubtless cut under the earlier opera-

re cut

tions on which the main objective was the pine, but spruce lumbering does

ve in-

not appear to have been general until the large pine was about exhausted.

ed out

We do not know just when the second phase began, but probably around the

isbury

middle of the nineteenth century.

1905,

The effect of the removal of these larger spruce trees was to open the

r pro-

crown canopy considerably more than when the old pines were cut. This

nts cut

gave an opportunity for spruce and fir seedlings to spring up in the openings.

ducing

and, in the larger ones, no doubt a certain amount of pine seeded in. In the

t day.

moister places young hemlock became established. The danger of fires was

and of the

materially increased by the dead tops lying on the ground and the drier con-

re the

ditions in the openings. Although the conditions favoring fire were not SO

from

bad as those following the heavier cuttings of later days, yet some of the

ducing

severest fires known on the island came during this period. In 1848 a fire,

vege-

started by a small boy, swept over the mountains of the northeastern part of

the island. In 1864 a conflagration utterly destroyed the lumber business of

re not

the Jordan brothers on Jordan Pond, and burned the slopes of Penobscot

t they

(Jordan) and Pemetic Mountains, as well as much neighboring forest.

V and

These and other fires seem to have killed most of the remaining virgin white

found

pine. In places the accumulated humus on which the trees were growing

There

was burned out, leaving only the bare rock. The slow process by which this

or at

bare rock is re-clothed will be described in another section.

e.

A

As the prices for lumber advanced, and the amount of large timber di-

Pond.

minished, more and more of the smaller spruces were cut, and even the fir.

trees

The transition appears to have been gradual, and by about the nineties the

past.

smaller as well as the larger spruces were being taken, though the forest was

forest

by no means cut clean. Thus the third phase grew gradually out of the

d fir.

second.

ise of

The third phase corresponds with an increased fire danger, since a great

large

deal more slash was left. and the more open condition of the forest permitted

to be

more rapid drying. There appear to have been many bad fires at the time

this type of operation was carried on. perhaps the worst of which was the

d was

Cadillac (Green) Mountain fire about 1889. though whether or not this was

long

directly attributable to logging we do not know.

22

BROOKLYN BOTANIC GARDEN MEMOIRS

Those areas which had the good fortune to escape fire became restocked

with spruce, fir and white pine, and, in the moister places, hemlock. Owing

to the greater amount of light, the proportion of deciduous trees was greater

than after previous cuttings. The new forests contained, mixed with the

conifers, a considerable proportion of red oak, red maple, white birch, and,

in the more sheltered spots, yellow birch. Beech and sugar maple were abun-

dant in the moister protected spots; not that their restocking was favored by

the larger openings since they are shade-enduring trees, but they were given

more opportunity to develop.

The fourth phase grew up recently with the development of the market for

pulpwood, which takes the small spruce and fir, and with the demand for lower

grade lumber. The spruce and fir are cut, sometimes peeled, sometimes not.

and hauled out to the road. For lumber, small portable sawmills move from

place to place wherever a tract of sufficient size to justify setting up can be

found. Everything down to even three inches at the small end is sawed up.

This is because of the practice of sawing in the round" or sawing alive,"

that is, without previously taking off a slab to square up the log. Obviously

this results in utilizing much material which under the older methods was

left in the tops to rot in the woods. Furthermore, it increases the amount

which can be cut out of the logs by saving much of the part that formerly

was thrown away as slabs. The deciduous trees, birches, maples, etc., are

cut up into cordwood or sometimes left standing.

This modern method of logging makes a practically clean cutting, nothing

being left except the defective and very crooked trees, and sometimes the

hardwoods. It results in considerable quantities of slash, which in the town-

ship of Bar Harbor must be disposed of, generally by piling and burning, but

in the two other towns can be left as a fire trap. Although the result, even

when the slash is eliminated, is unsightly and appears like ruthless devasta-

tion, the forest does not suffer as much as would appear-provided fire is

kept out. There generally follows an abundant restocking of white pine,

spruce, and fir, with red pine on the drier sites, and hemlock on the moister.

Fortunately, the sentiment in favor of fire protection has become so much

stronger, and the methods of protection SO much more efficient, that the

danger of fire, though by no means negligible, is comparatively small. For

the improvement with regard to fires a great deal is to be attributed to the

influence of the Lafayette National Park rangers, who, in the course of their

regular duties, are able to detect fires anywhere on the island as well as in the

Park itself. The example of the Park officials in extinguishing fires is fol-

lowed by private owners.

The cutting and burning of the forests, briefly outlined above, has been to

VEGETATION OF MOUNT DESERT ISLAND, MAINE

23

tocked

a certain extent responsible for the kinds of trees which grow on various parts

Owing

of the island today. The natural course of development which had been

reater

going on from the time the land was bare after the retreat of the ice, until it

h the

supported the highest type of forest of which the climate is capable, was ar-

. and,

rested and thrown back. This will be considered more fully below. Suffice

abun-

it here to say that the stretches of birch and aspen forests which cover such a

ed by

large proportion of the island with growth of little value are to be attributed

given

to past fires. The cuttings alone, without the fires, would have given young

forests of the more valuable species instead of the nearly worthless birch and

et for

aspen, much of it gray birch which is hardly fit even for firewood.

lower

Pitch pine, a picturesque tree, but of no value here since it seldom reaches

s not.

from

sufficient size to be worth sawing into even low grade lumber, has most prob-

ably increased in area since the arrival of the white man. This is because

an be

the barren rocky places on which it will grow, but where other trees are un-

ed up.

alive,"

able to survive, have been considerably increased by human interference,

chiefly by fires. The tree was no doubt fairly abundant before the white man

iously

S was

came, since the barren summits which Champlain mentions indicate the pres-

mount

ence of sites suitable for it, but it has been given a greater opportunity to

spread than it had before.

merly

., are

With the spread of pitch pine there has been an extension of the plants

over and among which it grows-its associates. Many of these are coastal

thing

plain species common in the sand plains of New Jersey and Long Island.

es the

Among these might be mentioned the huckleberry, Gaylussacia baccata, very

town-

abundant under the pitch pine and elsewhere on the island, the bearberry,

g, but

Arctostaphylos Uva-ursi, which extends even to California under moderately

dry pine forests, the yellow flowered heather-like Hudsonia ericoides, and

even

vasta-

others. Man's interference has thus caused an increase in many coastal plain

ire is

plants which thrive on the drier sites. The scrub oak, Quercus ilicifolia,

pine,

seems to be an exception in that it is confined to a single mountain. Acadia

ister.

(Robinson). But it may be that even this plant was more restricted in the

past than it is today.

much

t the

Man's influence on the vegetation has not been confined to the effects of

For

cutting and burning the forests, though the greatest change resulted from

to the

these two agencies. On Mt. Desert Island. as on many other islands along

their

the Maine Coast, there used to be a good deal of sheep raising. Sheep seem

in the

to have been introduced by the earliest settlers. and were not given up until

S fol-

recently, when it appears that certain restrictive laws made the industry un-

profitable. Since these forests, unlike the more open forests of the west,

een to

are unsuited to grazing, the sheep must have been largely confined to lands

cleared for pastures. and to old farms which had been abandoned. They may,

24

BROOKLYN BOTANIC GARDEN MEMOIRS

however, have had some effect in furthering the spread of certain plants,

particularly those which do best in the more open places.

Clearing of land for cultivation must be considered an important factor in

changing the vegetation, but the extent of its effect depends upon the extent

of the land suitable for farming. In some parts of the country, as in the

middle west and the eastern edge of the plains, where most of the land is

valuable for crops, the native vegetation has been almost totally destroyed.

Scientists endeavoring to find what the soil and climate will produce under

natural conditions are constrained to study strips along the railroads as the

nearest approach to remnants of the native plants. On Mt. Desert Island the

area which was cleared and devoted to crops and pastures was larger in the

past, before the opening of the west, than it is today. As with the rest of

New England, a considerable proportion of the farm-lands has been aban-

doned and allowed to revert to forest. Prof. R. T. Fisher, director of the

Harvard Forest, has stated that the 200,000,000 board feet of white pine

which is yearly cut for box boards in Massachusetts comes practically all from

land which was in farms at the time of the Civil War. The amount of

coniferous forest on Mt. Desert Island abandoned farms. while much smaller

in proportion to the total area than on similar land in Massachusetts, is consid-

erable. In many cases the re-establishment of the forest has gone SO far that

it is practically impossible to tell from present appearances whether or not

the land was once cleared. Since the forest on such lands does not appear

to differ markedly from that on other parts of the island, no attempt has been

made to map or study it separately.

SUMMARY

Mt. Desert Island, Maine, is of exceptional scientific interest as a meeting

ground of northern and southern forms of both plants and animals. We are

here concerned only. with the plants and their environment.

The chief rock formation of the island is granite, which has been left after

ages of erosion as a relatively high range extending in a southwesterly-north-

easterly direction across the island, and attains an elevation of 1532 feet at

its highest point. Glaciation has cut the range into a number of more or less

isolated peaks with their long axes running approximately north and south.

But the mountains still act as a barrier_across the island sufficient to create

noticeably different conditions on the northern as compared with the southern

parts of the island.

After the last ice retreat the island was submerged to approximately 210

feet below its present level.

The soils are of glacial origin except for marine clays and silts deposited

during submergence. The chief soil is a reddish brown glacial till, more or

less stony, which on certain slopes below 210 feet has been somewhat re-

worked by wave action. Deposits of sand and gravel occupy a relatively

small proportion of the island. Pockets of blue marl and of a fine grey silt

cover considerable areas below the 200 foot contour. The hills are largely

without soil, and characterized by large expanses of bare granite, varying

from perpendicular cliffs to rounded domes.

A distinct layer of raw humus or " duff," unmixed with the mineral soil,

overlies most of the surface except for certain moist and sheltered valleys

where decomposition keeps pace with formation SO that the humus goes into

the soil. In places this humus blanket has been burned off by past fires, ex-

posing the bare rock and soil.

The coastal plain plants which form such an unusual and interesting com-

ponent of the vegetation probably reached the island by way of a land bridge

formed by an extension of the coastal plain above the sea from New Jersey

to Newfoundland.

Previous to its settlement by white men, the island had been repeatedly

subjected to fire by the Indians to drive out the game. When discovered by

Champlain in 1604 the summits were bare rock, and the forest contained tall

pines standing above the main canopy of spruce and fir, with white birch in

mixture. Even before its permanent settlement, the annals of which begin

143

LITTORAL VEGETATION ON A HEADLAND OF MT. DESERT

ISLAND, MAINE. I. SUBMERSIBLE OR STRICTLY

LITTORAL VEGETATION 1

DUNCAN S. JOHNSON AND ALEXANDER F. SKUTCH

Purpose

In the present investigation we have undertaken to determine the precise

limits of distribution, vertically and horizontally, of each littoral plant and

plant association found on a high, rocky point of Mt. Desert Island, Maine,

known as Otter Cliffs. Our object was the discovery of the external con-

ditions limiting this distribution.

Most of the observations to be recorded were made during July, August

and early September of the years 1923 to 1925. In March 1927 the junior

author spent three days studying the late winter flora of our area, and the

senior author followed the seasonal development of the vegetation from June

to September of the exceptionally cool and backward summer of 1927.

Area and Methods

Otter Cliffs are on the south side of the island, close by the Ogden Station

of the Mt. Desert Island Biological Laboratory, and are completely exposed

to the heavy surf of the open Atlantic. They lie near 44° 19' N. latitude

and 68° II' W. longitude. Our work was carried on from the Weir Mitchell

Station of this laboratory as a base. The area most carefully studied extends

I50 feet north and south, and 300 feet east and west, and includes elevations

from - 8 to + 50 feet (Chart I). It was selected because of the widely

varied habitats provided by the rock surfaces of many different slopes and

exposures, and by tide-pools of very different sizes at many different levels.

It embraces some bottom at 4 to 8 feet below mean low water, of rocky or

gravelly character, and a bit of coarse shingle and boulders between 7 and 13

feet above low water, while the rest of the littoral zone is of granite or schist

cliffs and ledges, with some trap dikes. Not until the 20-foot level, IO feet

above mean high tide, is reached do we find even minute pockets of soil in

1 Botanical Contribution No. 87 from the Johns Hopkins University. The authors

gratefully acknowledge here the courtesy of the Trustees and of Director Ulric Dahl-

gren of the Mt. Desert Island Biological Laboratory in affording them the facilities of

the Laboratory for carrying on this work. They also here express their thanks to

GPD

Superintendent George B. Dorr of Lafayette National Park. for help in fastening our

tide-stake to the ledges, and for transportation to the area in March 1927. They are

indebted also to Doctor A. S. Hitchcock for naming the grasses and to Doctors M. A.

Howe, Albert Mann, and W. R. Taylor and J. E. Tilden for identifying various algae

collected in the area studied.

188

Ecology 9 (1928): 188-215

WILLIAM H. PROCTER (1872-1951)

Relatively unknown today by Mount Desert Island residents and visitors,

William Procter played a very significant role in contributing to the

scientific knowledge about what is today Acadia National Park. An heir of one

of the founders of the Procter and Gamble Company, he dedicated the later

part of his life to the study of insects on Mount Desert Island.

Over the course of 27 years, starting in 1918, Dr. Procter spent a majority of

his time combing the island for insects. He ultimately published 7 scientific

volumes summarizing his collecting efforts; no fewer than 439

families, 2,660 genera, and 6,578 species and subspecies were documented!

His field notes and ~ 20,000 pinned and wet specimens are now permanent-

ly preserved at the William Otis Sawtelle Collections and Research Center at

Acadia National Park. Since its arrival in 2000, scientists from as far away as

Russia have come to use the collection for research purposes (it was

previously housed at the University of Massachusetts).

Dr. Procter's collection represents an incredibly rich and unique information base that is unequaled at most other

national parks. Because of his dedicated studies, scientists today can now make comparisons about the past and

present species diversity and distribution in order to learn about how changes in climate, land use, and the 1947

Mount Desert Island fire affected the island's fauna.

Dr. Procter played a role in helping to establish the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory (MDIBL), served on

an advisory board at the Columbia University Zoology Department, was a board member of the Wistar Institute and

a Trustee of the American Museum of Natural History. He contributed financially to many scientific organizations,

including the Entomology Society of America, Society of Sigma Xi, and the Research Society of America. In 1950,

Sigma Xi established the William Procter Prize for Scientific Achievement; Stephen Jay Gould, Jane Goodall, and

E.O. Wilson are several of the recent winners.

There are many people who contributed time, money, and energy to help protect Acadia National Park. Dr. William

Procter was a distinguished natural scientist who worked tirelessly to catalog some of the Park's fauna well before

the National Park Service took an interest in natural resource management. Now thanks to his efforts, park

managers and the scientific community have vital information to help characterize and assess the health and

condition of Acadia National Park's ecosystems.

David Manski

Chief, Division of Resource Management

Acadia National Park

53

Acadia National Park (Nature Notes)

Page 2 of 2

See

Sieurde

thants Publ.

NATURE

White pine

VOL.3-NO.1

NOTES

JANUARY-

FEBRUARY,

1934

Arthor wike

Hemlock

(Red) spruce

Black

Confers

of

MOUNT DESERT

Readia

ISLAND

area approve 300 37 mr.

ACADIA NATIONAL PARK

BAR HARBOR, MAINE

Department of the Interior: Office of National Parks, Buildings. & Reservations.

> Cover

Next >>>

nature_notes/acad/vol3-1.htm

18-Mar-2016

http://npshistory.com/nature_notes/acad/vol3-1.htm

8/14/2019

Acadia National Park (Nature Notes)

Page 1 of 6

Acadia National Park

Nature

Notes

NATURE NOTES FROM ACADIA

Volume 3

January-February, 1934

Number 1

THE TREES OF ACADIA NATIONAL PARK

By Arthur Stupka, Park Naturalist, Acadia National Park

The trees of Acadia National Park, Mount Desert Island, Maine, are

essentially northern in character, as the region belongs to the so-called

Spruce and Northern Hardwoods division. Spruces are dominant, the

red spruce making up a considerable portion of the coniferous stand

over much of the island and the white spruce replacing it as the most

abundant species along a large portion of the ocean front. Other trees

which make up an appreciable amount of the total stand include white

pine, red pine, white birch, gray birch, arbor vitae, balsam fir, red

maple, red oak, hemlock, and aspen. Thoreau, with characteristic

fitting and poetic phraseology, called this the "arrowy Maine forest."

SECTION I. THE CONIFERS

Key to the Conifers of Acadia National Park

1. Trees with needle-like leaves

2

1. Trees with small, scale-like leaves

Arbor vitae

2. Needles evergreen, remaining on tree in winter;

3

needles borne directly on branches

2. Needles deciduous, dropping off tree in fall;

Larch

needles borne on short spur-like side branches

3. Needles borne in clusters of 2, 3, or 5

4

3. Needles borne singly on branches

6

http://npshistory.com/nature_notes/acad/vol3-1b.htm

8/14/2019

Acadia National Park (Nature Notes)

Page 2 of 6

4. Needles 5 in a cluster, 2 to 5 inches long

White pine

4. Needles 3 in a cluster, It to 4 inches long

Pitch pine

4. Needles 2 in a cluster

5

5. Needles 4 to 6 inches long; cones symmetrical,

Red pine

even-shaped

5. Needles 4 to 1 inch long; cones asymmetrical,

Gray pine

incurved

6. Needles on all sides of branch, pointing outward

7

in all directions; branches with needles, round in

appearance; needles not lighter colored on under

side

6. Needles seemingly on only two sides of branch;

9

branches with needles, usually flattened in

appearance; needles pale green or whitish on

under side

7. Needles bluish-green or bluish, dull and blunt

8

7. Needles yellowish-green, shiny and sharp-pointed

Red spruce

8. Scales on ripe cones stiff and rigid, ragged-

Black spruce

toothed

8. Scales on ripe cones flexible, not toothed

White spruce

9. Needles pale green on under side with white line on

Hemlock

each side of midrib; trunk of tree free from blisters;

cones 3/4 inch long and pendant

9. Needles pale green on under side with light dots;

Balsam fir

trunk of tree with resin blisters; cones 2-4 inches long

erect

Four species of pines are

native to the region and of

these the white pine (Pinus

strobus), emblem of Maine,

the Pine Tree State, is most

abundant. This, the noblest of

our trees, has been known to

Gray

Pine

exceed 4 feet in diameter and

150 feet in height, and has

long been regarded as the most

valuable timber tree in

northeastern America. Its soft

bluish-green needles are

arranged in clusters of 5, the

lateral branches are whorled, and the cones, usually measuring from 5

to 8 inches in length, are larger than those of any other native

coniferous tree in the northeastern states.

The red pine Pinus resinosa, whose needles 4 to 6 inches in length,

are longer than those of any other of our needle-bearing trees, is tall

http://npshistory.com/nature_notes/acad/vol3-1b.htm

8/14/2019

Acadia National Park (Nature Notes)

Page 3 of 6

and straight, with a pyramidal crown, dark green foliage, and reddish-

brown bark. This bark, like the bark of the yellow pine of the west,

tends to break up into broad reddish plates. The needles are arranged

in bundles of 2. The symmetrical cones are somewhat spherical and

about 2 inches long. It is valued highly as a timber tree and often goes

by the name of "Norway pine."

The pitch pine (Pinus rigida),

very picturesque in its exposed

rocky habitats, is usually low-

growing and has an irregular

scraggly crown. Its ovate

cones may persist on the

gnarled branches for many

years. This is the only native

Pitch

pine of Mount Desert Island

pine

whose needles are arranged in

x1/2018

clusters of 3.

A boreal species, the gray, jack, or Labrador pine (Pinus banksiana),

finds its southern coastal limit on Mount Desert Island. It is rare here,

being represented by a small stand of trees to the south of Cadillac

Mountain. On a portion of the Acadia National Park area which

is

located just across the by on Schoodic Peninsula, this pine is an

abundant species. For the most part it grows considerably dwarfed

and shrubby, and its small, tough, asymmetrical cones persist on the

tree for many years. Its very short gray-green needles are arranged in

clusters of 2.

White

pine

The larch, also known as tamarack and

hackmatack (Larix laricina), is a

common tree of the sphagnum bogs of

the island. Unlike all other of our

coniferous species, it sheds all its

needles every fall, putting on new

twig

ones the following spring. These

in winter

needles are borne on dwarf spur-like

side branches. As it resembles a

http://npshistory.com/nature_notes/acad/vol3-1b.htm

8/14/2019

Acadia National Park (Nature Notes)

Page 4 of 6

Larch

x1

symmetrical pine in general form, the

tree has a striking resemblance to a

dead conifer in winter. It is a medium-sized, light-loving tree with a

straight trunk, very small ovoid cones, and short clustered needles.

The range of the larch extends across the continent, and it is found in

the north within the Arctic Circle.

Three spruces are native to Acadia National Park. The black spruce,

also known as swamp spruce (Picea mariana), is a tree characteristic

of our sphagnum bogs, although it is not infrequently found in a more

or less stunted condition on dry mountain slopes where it may appear

ragged and uneven in its habit of

growth. Usually it is smaller than the

other native spruces and the scales on

its ripened cones tend to be stiff, rigid,

and ragged-toothed. It bears needles

which are dull and blunt. The red

Red

spruce (Picea rubra) is one of the most

spruce

abundant of our trees. It has narrow

x1

conical crown and a straight slightly

tapering trunk which usually attains a

height of 60-80 feet. The branches are

slender, the cones ovoid, and the

needles a shining dark green or

yellowish-green about one-half inch

long. Whereas the other spruces have

needles which are blunt at the ends,

the needles of the red spruce are

sharp-pointed. Next to the white pine,

this is the most valuable timber tree in

Maine. The white spruce (Picea

glauca), a tall handsome tree

especially valuable for paper pulp,

grows best right along the ocean front

of Mount Desert Island. Its branches,

long and stout, bear dense attractive

grayish or bluish-green needles which

sometimes are characterized by an

odor which accounts for the local

name of "skunk spruce" or "cat

spruce." As in all spruces, the oblong

cones are pendant, and when ripe, the

cone scales are flexible and not

toothed.

Although in cool moist ravines the

hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) grows as

far south as Alabama, it attains its

greatest size and beauty in the Acadian

White spruce

http://npshistory.com/nature_notes/acad/vol3-1b.htm

8/14/2019

Acadia National Park (Nature Notes)

Page 5 of 6

region. In its preferred habitat it is a

fairly common tree on Mount Desert Island where old specimens up

to four feet in diameter are to be found. Its short flat needles are

glossy dark green above and pale

green beneath, there being a white line

an either side of the midrib on the

under surface. Although appearing

two-ranked, the needles are spirally

Hemlock x1

arranged around the twigs. The cones,

oblong in shape, are about three-fourths of an inch in length -

considerably smaller than the fruits of other conifers with which the

hemlock is sometimes confused. Where goodly stands of this graceful

and symmetrical tree grow, the summer visitor finds himself in the

haunt of the winter wren, one of the finest of our feathered songsters

and the veritable spirit of the cool hemlock forest.

The balsam fir (Abies balsamea), the only fir native to Maine and the

other New England states, is a common conifer in Acadia National

Park. It is a tree of medium size, usually under 40 feet in height, and

the trunk rarely exceeds 18 inches in diameter. Its bark, smooth and

grayish-brown in color, is covered with projecting blisters which

yield the pungently aromatic Canada balsam of commerce. The

fragrant needles are arranged SO that they give the twigs a flattened

appearance. The dark purple cones, usually two or three inches long,

are cylindrical and stand upright on the branches - a characteristic

which distinguishes the fir

from other conifers with which

it may grow.

The arbor vitae, often known

as white cedar (Thuja

occidentalis), is a medium-

sized tree which has its best

development in swamps and

bogs where it may be found in

pure stands. Its trunk is tapering and the bark, often used by the red

squirrel for the spherical nests which that animal builds, separates into

long thin strips. The scale-like overlapping leaves, aromatic when

crushed, are arranged to make a flat frond-like spray on which the

small oblong cones are borne.

The dwarf

juniper,

creeping

juniper, and

American yew,

sometimes

confused with

the young of

http://npshistory.com/nature_notes/acad/vol3-1b.htm

8/14/2019

Acadia National Park (Nature Notes)

Page 6 of 6

some of the

trees already

mentioned, are

low-growing

evergreen

shrubs with

needlelike

Balsam fir

leaves. They

x1

are common in

some portions

of the park and

are readily

distinguished in that they do not bear cones. Their fruits are small and

berry-like, those of the junipers being blue covered with a pale bloom

while those of the yew are a bright scarlet in color.

Note: Articles on the deciduous tree of Acadia National Park will

appear in future issues of "Nature Notes from Acadia."

>>

nature_notes/acad/vol3-1b.htm

09-Jan-2006

http://npshistory.com/nature_notes/acad/vol3-1b.htm

8/14/2019

Acadia National Park (Nature Notes)

Page 1 of 3

Acadia National Park

Nature

Notes

NATURE NOTES FROM ACADIA

Volume 3

January-February, 1934

Number 1

A WINTER RAMBLE

"Come see the north-wind's masonry."

- Emerson

The coast of Maine lies gripped in the icy hold of one of the most

severe winters on record. Harbors are ice-locked and deep snow

everywhere blankets the out-of-doors. On clear days the ermine-

coated summits of the Mount Desert Island mountains, heavily

armored in snow and ice, glisten with such dazzling brilliance that

one might almost be lead to believe they had undergone some

herculean polish in the night.

Let us buckle on our snowshoes at Sieur de Monts Spring - a place

known to every Acadia National Park visitor - and make fresh tracks

through the snowy woods in the general direction of the Tarn. Close

to the Abbe Museum we cross the tracks of a gray squirrel - perhaps

one of the same animals which harvested many of the acorns and

beech nuts in that vicinity last autumn. Upon following these tracks

we discover where the animal dug into the deep snow and fed upon a

few acorns. Being in the habit of storing only small quantities of food

here and there over the forest floor, the gray squirrel must necessarily

dig deeply for his winter supplies. Surely, to find provisions which

now lie buried under one and one-half to three feet of snow implies a

remarkable memory. White-foot, the big-eared dark-eyed woods

mouse, had likewise crossed the snow here but recently, leaving a

http://npshistory.com/nature_notes/acad/vol3-1c.htn

8/14/2019

Acadia National Park (Nature Notes)

Page 2 of 3

dainty little tell-tale pattern which disappears under the low snow-

laden limb of some conifer.

For a moment we stop to admire a grove of young beeches which

still retain an appreciable number of their papery leaves. Whereas in

summer these leaves were dark green in color and in autumn a rich

coppery brown, they now are of a soft light fawn color - especially

attractive against the snow.

The brook which flows from the nearby Tarn gurgles pleasantly in

those few spots which remain open, as though defying the frigid

fetters of winter in its own tongue. While listening to its cold icy

murmur a mite of a dark brown stubby-tailed bird flies up nervously,

complaining against our intrusion. He, the winter wren, has

apparently lived through all these bitter cold months in this

immediate territory, finding shelter under the many little bridges or

under the streambanks where the roots of trees have been exposed.

No doubt he finds a few stone flies and possibly other stream insects

here. E. H. Forbush, in his classical "Birds of Massachusetts," makes

the following interesting statement: "As a winter bird in the latitude

of New England, this wren is a disappointment. A few remain here in

mild winters, but those that attempt to brave out a severe one in New

England usually perish miserably. In the spring their dead bodies are

found occasionally under piles of lumber or wood. Most of them

winter in the South." Our bird, therefore, must truly be some defiant

hardy exception, for the present winter is one of the most severe ever

to be recorded. Admiring the fortitude of this feathered elf, we

proceed with our ramble.

Upon coming to the Tarn, now burdened with a considerable

thickness of ice, we stop to view the heavily snow-and ice-coated

slopes of Huguenot Head and Flying Squadron Mountains - the east

and west sides of an ancient trough through which the glaciers of

many thousands of years ago pushed out into the sea. The former

mountain, supporting a dense stand of pitch pines, appears very

much as it does in summer, but Flying Squadron, with a

comparatively sparse growth of spruces, has its eastern slope

whitened by a heavy blanket of snow and ice.

From here we cross the nearby Otter Creek road and tramp over the

drifted snow which lies in the little valley at the north foot of

Huguenot Head. It is in protected valleys such as this one where,

after a heavy snowstorm, the conifers stand arrayed in some of

winter's most picturesque habiliments. In places young trees as high

as one's head, completely draped in the snowy substance, appear as

though they might be the tents in which the boreal troops are

encamped, for winter concentrates his forces in these ravines as

though they were strategic points.

http://npshistory.com/nature_notes/acad/vol3-1c.htm

8/14/2019

Acadia National Park (Nature Notes)

Page 3 of 3

Making a wide circle through the snowy valley we climb Little

Meadow Hill, a stronghold for the pitch pines. Before going far

through this quaint low forest the tracks of red squirrels, crossing and

recrossing over the snow, hold our interest, and occasionally we

come upon the temporary feeding places of these animals - a litter of

cone scales, bark flakes, needle-bearing twigs, etc. Evidently a

number of squirrels come here to feed on the abundant fruit of the

pitch pines. While watching an impetuous chickaree dashing through

the trees sending burdens of snow a-flying, a flock of about 20 red

crossbills. twittering half-plaintively as they fly, suddenly wheel and

settle in the top of one of these low scraggly pines. Approaching

closely we admire the attractive brick red males who investigate the

cones for the seeds which might be within. Only momentarily do

they linger and then are off again in close formation, twittering as

they disappear. These birds, along with the white-winged crossbills,

have been on Mount Desert Island in goodly numbers during the

present winter.

And SO we ramble on, encountering other animals and seeing other

sights. Hard though it may be for both man and beast, the winter has

infinite charms.

- Arthur Stupka

>>

nature_notes/acad/vol3-1c.htm

09-Jan-2006

http://npshistory.com/nature_notes/acad/vol3-1c.htm

8/14/2019

1001

10-23

(May 1929)

0-7410

UNITED STATES

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

ACADIA

NATIONAL PARK

FILE No. 715-02

PART

1

ACADIA

FLORA, FAUNA, NATURAL PHENOMENA, ETC.

BEARS

LAST DATE ON TOP

IMPORTANT

This file constitutes n part of the official records of the

National Park Service and should not be separated or papers

withdrawn without express authority of the official in charge.

All Files should be returned promptly to the File Room.

Officials and employees will be held responsible for failure

to observe these rules, which are necessary to protect the

integrity of the official records.

ARNO B. CAMMERER,

6-7410

Director.

Scanned with CamScanner

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Acadie National Park

Bar Harbor, Maine.

COPY

March 17, 1937.

Mr. Roy K. Dennison,

House of Representatives,

Augusta, Maine.

Dear Mr. Dennison:

I want to write you a line to express

my strong sympathy with what you were quoted in the

newspapers as saying at the Legislative hearing on

March 11th, with regard to establishing a bounty on

bears, concerning steel traps. I know from actual

experience obtained in connection with my work in

charge for the Government of this national park as

well 03 from what others have told me out of their

personal exporience the great suffering caused by

Steel-trapping, and the inevitable cruelty of it

which the world will one day come to realize and

condemn.

Years ago I took part in EL campaign against steel

trapping in the State of Massachusetts, my former home,

and a law was passed by the Legislature prohibiting

it for the measure had strong support; but it aimed, as

1t was drawn, at too absolute EL prohibition to be 1m-

mediately practical and came to nought through lack of

funds for 1ts enforcement. Extremes tend invariably

to be self-defeating and the main thins is to swoken

public conscience to the suffering caused and to arouse

public opinion against 1t.

The trapping of bears 1n this State is inde-

fensible on any grounds; for the hunter's rifle, to the

State's great gain in the open season, is ample to

protect human safety and prevent too serious depredations

upon open farmlands.

Believe me

Yours sincerely,

(signed) George B. Dorr

GBD-0

Superintendent.

Scanned with CamScanner

NON IN 10 plo1

GRIDE NEW DUE WIN

DRIN m

to

DEPARTMENT OF Ti

TERIOR

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

WASHINGTON

February 6, 1937.

Mr. George B. Dorr,

Superintendent, Acadia National Park,

Bar Harbor, Maine.

Dear Mr. Dorr:

Your letter of February 3 and clipping from the Port-

land Press Herald relative to roadside animal exhibits have

been read and commented upon by several members of the Wash-

ington Office.

Your work in initiating the measure to prevent exhibit

of captive wild animals along the highways of Hancock County

is very commendable. This achievement illustrates the type

of influence our national parks and their Service personnel

should exercise on the surrounding communities.

We have been informed that only recently the State of

Pennsylvania passed a similar bill, preventing the showing

of wild animals along the highways. We join with you in

hoping that the bill to prevent such exhibits over the entire

State will receive favorable action.

Sincerely yours,

James 0. Stevenson,

Acting Chief,

Wildlife Division.

cc Wildlife Division - San Francisco

wktmnm

Scanned with CamScanner

bill PEMBO

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Cabalane

Acadia National Park,

Bar Harbor, Maine.

good with

February 3, 1937.

the

Mr. A. E. Demaray,

Associate Director,

National Park Service,

Washington, D. C.

Dear Mr. Demaray:

I think this, of which the newspaper

clipping from the Portland Press Herald tells, may

interest you as showing the influence the Park is

having along good lines.

Last September two bears kept, none too humanely,

along the roadside in a cage at a place of entertainment

between Ellsworth and Bangor, in this county, broke out

and with the memory of rough treatment in their captivity

renkling, attacked and killed the proprietor and his a.s-

sistant. The bears were shot but had one glorious moment

of revenge which were hard to grudge them!

Taking advantage of this as an opportunity to do away

in this county at least with what has always been abhorrent

to me, I had asked our State Senator from this district to

introduce a bill to prevent wild animals' being kept in

centivity along the roadsides as an adjunct to such

places in any portion of the County and this bill has n LOW

been favorably reported on without opposition by both

branches of the State legislature.

Entering 1t, moreover, brought attention to the

subject and has led to the introduction of another bill

introduced quite Independently for the regulation, if

not the prohibiting, of all similar exhibits of wild

animals in confinement the whole State over, and this, too,

seems likely to be favorably acted on.

Yours sincerely,

GBD-0

Scanned with CamScanner

7/29/2020

Xfinity Connect Bears Printout

Judith H Connery

7/29/2020 10:32 AM

Bears

To Eppster2@comcast.net Copy

Charles D Jacobi

Charlie Jacobi

Hi Ron,

Attached is the "Bears" file. (Please excuse the duplicated scan of the cover.)

Yes, who would have thought it to contain correspondence to and from Mr.

Dorr?! I wonder how many other treasures are hiding in NARA? I hope that

once a vaccine is available, Charlie and I will be able to continue that hunt.

The file name provides information about where it was found, based on the

Record Group 79 Finding Guide. Let us know if you need us to decipher it.

Also, Charlie's government email address has changed to a "partner"

account: charlie_jacobi@partner.nps.gov

You can also stay in touch with him at: potholescharlie@gmail.com

While I still have my old government email address (not sure why....), I most

often check my private email account at judy.connery@gmail.com so that's

the best way to contact me.

Thanks for reaching out, and please let us know if we can provide any other

materials.

All the best to you, Ron, and please stay healthy!

Judy

NPS - Unknown - Bears. NACP RG79 P10 pg400 B809 F715-02 Part 1-

annotated.pdf (1 MB)

7/29/2020

Xfinity Connect Re_Bears Printout

eppster2@comcast.net

7/29/2020 12:40 PM

Re: Bears

To Judith H Connery judy_hazen_connery@nps.gov>

Judy,

File received. Thank you.

I updated my address book.

I

empathize with you regarding the ways in which the pandemic have

impeded your research on the AH. Before the pandemic I began to

secure through ILL copies of about a dozen park administrative histories

written over the past thirty years and not on the NPS website It is quite

striking how much their differ, especially in their narrative delivery to

future park managers. Some are dry as dust, rapidly escaping early

park history for detailed statistical reporting of more current studies;

others achieve a lively balance between history, policy, local and distant

development of managerial priorities and the park staff that made it all

happen. I hope that the NPS is documenting how Covid has impacted

the park system in ways large and small.

You should know that I am having conversations with Ruth Eveland at

the Jesup Library about her interest in my two file drawers of information

on Dorr's paternal and maternal ancestry. Originally I thought that this

would be included in with the file cabinets of documents that Sheridan

Steele and Marie accepted for the park archives. I began to doubt that

ANP park researchers would have much interest in Dorr's 17th through

19th century ancestors. After considerable reflection I recently offered

these ancestry documents to the Jesup where they would be more

accessible to the public in their new Special Collections facility attached

to the 1911 building that Dorr built--where they will complement the

JDRJr. and Deasy-Lynam documentation donated by Doug Chapman.

All the best to you and yours. Stay safe!

https://connect.xfinity.com/appsuite/v=7.10.3-6.20200722.052513/print.html?print_1596040865075

1/3

G.B. Dorr Society

7/27/2020.

Caulee Judith peabe County

"Bears file in N.A.

GRD was actual, a dedecaed

overal rights aboorte Plesto

10 Pach Rayer x bese cubs. File

contain can re captured avade

a woodside attraction - h

wa agest

Request

letter to a. B. Desario 2/3/37

h 1938, Carl person incident,

Didast coveral CANP 11/2/3

Death on dest Schoolie new

frest retailed

Ocate of Past fever Read to proboxy

Peal Foure tooh position,

brought natural littry shalles to AdP.

Renja desting carear in NPS,

worlf at Ocadia x first pal

netrudent at thevardook N.P.

Returned in 1869, deed zu

Raques Beach.

2

Charlie

4,000 lbs stored

Interview 1. stord t

the

Explanation uses By ccc + dons.

Seep. John good, deed Dec. 2019, OBIT,

NPS - 1958 beja at AND

B.S. /M.S. geology deposit

Chief Vat yellowstore 1960 58

folt yournite t Eaceledes

8/24/08. Good moro to

Sepnal Develor

Ash fa copy

Eaphanged u nept of pervorat boundary

" a more Coost Heiega Tuest,

x other partnershops.

2

cameeve is UPS issues

a

visitaba as mangfed issue.

a

And Release or bon for

responsed decesson makes.

followd Keith letter

I

7/26/2020

Xfinity Connect RE_G_B_ Dorr Society event Printout

Lisa Horsch Clark

7/23/2020 8:58 PM

RE: G.B. Dorr Society event

To RONALD

Ron,

Double checking I sent you the login invitation for the zoom meeting on Monday. Need anything else

from me? We did our rehearsal they have amazing stories!

Lisa

I am delighted you can join us at noon on Monday, July 27 for the 16th Annual George B. Dorr Society

event. It is sure to be a fun, storytelling gathering with Judy, Charlie, and other park experts.

To join the meeting, click this link

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/81186610303?pwd=KOtYZUNqYUg0NkZJSIIMbURHdDhmdz09.The meeting

ID is 811 8661 0303 and the password is 272853, in case you need to use them.

If you have not used Zoom on your laptop, phone, or tablet before, please click the link in advance of the

meeting and download any software you might need. If you would prefer, you can also join the meeting

by telephone by calling 1 646 558 8656 and using the meeting ID is 811 8661 0303 and the password is

272853.

If you are not familiar with Zoom, I am very happy to help you learn the program. Just let me know that

you need help!

Thank you for helping to protect Acadia with all your past and future gifts. We appreciate you!

With gratitude,

Lisa

4/26/2015

XFINITY Connect

XFINITY Connect

eppster2@comcast.net

+ Font Size

Re: beaver project

From : Ronald Epp

Sun, Apr 26, 2015 10:45 AM

Subject : Re: beaver project

To : Rebecca Cole-Will

Cc : Marie Yarborough

Dear Becky (cc: to Marie),

This has not been a simple task. I've referenced the 2012 park management finding aid and suggest that

those interested look at the Vernon Bailey's 1925 article on beavers in ANP (B. 173, f.34) which I have

not examined but may be useful.

Regarding the claim attributed to Dorr that the park is incomplete without beavers, I strongly doubt that

Dorr would have said that. The park was always a work in progress; it was contrary to his nature to

see one final piece complete the picture, especially when you read his memoirs and see repeated references

while he was in his eighties to all that he had yet to do.

What we may have here is a piece of cultural memory, not based on a specific reference but on what has

transmitted, rephrased, obscured over time, and even effaced. This is my plight as well for I have a vague

recollection of Dorr writing about the introduction of a pair of beavers despite the fact that I can't recovery

it in my many layers of relevant historical data. I suspect it is to be found in RG79 at the National Archives.

Do not lose faith! We do have documentation from John D. Rockefeller Jr. The Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC)

contains two relevant letters on beavers in ANP, one to A. Cammerer dated June 22, 1928 and the other to Dorr

on July 29, 1929. I will put copies of these in the mail to you tomorrow along with Dorr's response

to Rockefeller's

extermination plan dated August 2, 1929. There is a separate beavers folder in Box 83, folder 824 in the RAC

Office of Messrs. Rockefeller Records, Homes (Seal Harbor). Series I. I have not examined this but a call to

an RAC archivist will likely get you copies; Asst. RAC Director Michele H. Beckerman has worked with me

for more than a decade and can help you with the process (914-366-6342).

Finally, my view is that Dorr introduced (or re-introduced) beavers in the late teens or early 1920's. They

were prolific and within a decade resulted in the issues JDR Jr. describes. Several years later on June 13, 1932

Director Horace Albright writes to JDR Jr. that "Mr. Dorr doubtless told you that with the cooperation of your

trapper the beavers will be taken from park waters." (Worthwhile Places. Ed. Joseph Ernst. RAC: 1991. Pgs. 126-127.).

But Dorr's successor, superintendent Hadley, still had beaver issues in 1950. I strongly suggest that Dorr's

interest never was in exterminating beavers. He made faint concessions to JDR Jr. but that would not prevent

him from relocating beavers to areas outside park boundaries. Where they traveled was not his doing.

Ironically, the park seems to have taken an about face in the 1980's on the issue of beavers when it named its visitor

information publication The Beaver Log.

Becky, do have Bruce keep me abreast of his inquiries into this matter. See you May 18-20th.

All the Best,

Ronald

https://web.mail.comcast.net/zimbra/h/printmessage?id=286451&tz=America/New_York&xim=

1/2

4/26/2015

XFINITY Connect

From: "Rebecca Cole-Will"

To: "Ron Epp"

Sent: Saturday, April 25, 2015 5:33:30 AM

Subject: beaver project - quote from Dorr?

Hi Ron,

Have you ever run across this quote from. GBD? Erickson is. COA student working on a beaver project for our biologist, Bruce Connery.

Thanks,

Forwarded message

From: Connery, Bruce

Date: Saturday, April 25, 2015

Subject: COA. beaver project

To: Rebecca Cole-Will

Erickson asked ."I have often heard people quote Dorr as saying that the park was not complete without beavers. Do

you have any idea where he said that? I'd like to quote him too :). I'm checking IRMA now."

I

have never heard of this quote but wonder if you or a friend with one of the historical societies might have heard of it? No rush on

an answer.

Hope you are feeling better.

b

--

Bruce Connery

Biologist

Acadia National Park

207-288-8726

Rebecca Cole-Will, Chief of Resource Management ~ Acadia National Park, 20 McFarland Hill Drive, PO Box 177,

Bar Harbor, ME 04609 ~207.288.8720 ph., 207.288.8709 fx.

https://web.mail.comcast.net/zimbra/h/printmessage?id=286451&tz=America/New_York&xim=1

2/2

Boston Society of Natural History Library

Page 1 of 17

SPECIALIZED LIBRARIES & ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS

Archival Collections &

HOME

SEARCH THE

COLLECTIONS

FINDING KIDS

Specialized Libraries

ABOUT

Digital Archive

Hancock Collections & Archives

Document LA

LA dis Subject

Home I Archives I Hancock Memorial Museum

LA Comprehensive

Bibliographic Database

The Building of a Library

LA Obscura

by

Public Art in LA

Dorothy Halmos

from

Archival Collections

Coranto: journal of the Friends of the Libraries, University of Southern

California

Volume V Number 1 & 2 to Volume VI Number 1, 1967-1969

ARC Home

About ARC

Contact Us

Search ARC

USC Libraries

& Resources

Homer

USC

Dorothy Halmos (d. 1998) was Librarian of the Hancock Library of Biology and

Oceanography from the mid 1940s through the 1970s. Her mark on USC is evidenced in

the following article, which appeared from 1967 to 1969, in the Coranto: journal of the

Friends of the Libraries. It recounts the development of the library of the Boston Society of

Natural History, which is the foundation of the Hancock Natural History Collection.

The University of Southern California is fortunate to posses, as the basis of its Hancock

http://www.usc.edu/isd/archives/arc/libraries/hancock/halmos/dhart.htm

12/22/2004

Boston Society of Natural History Library

Page 9 of 17

L. C. D. de Freycinet, Voyage autour du monde sur les corvettes de S.M.