From collection Creating Acadia National Park: The George B. Dorr Research Archive of Ronald H. Epp

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

Page 62

Page 63

Page 64

Page 65

Page 66

Page 67

Page 68

Page 69

Page 70

Page 71

Page 72

Page 73

Page 74

Page 75

Search

results in pages

Metadata

[Series III] Boston-The Back Bay

Boston : The Back Bay

Let's Go - Boston - Birth of the Back Bay

Page 1 of 2

Home

Destinations

Bookstore

Resources

Forums

Features

BOSTON

LET'S GO

Boston Life & Times / History / 19th

Century: Boston Brahmins / Birth of the Back Bay

LET'S GO

Birth of the Back Bay

Search Let's Go

These immigrant groups were greeted with a less

than kindly reception from the Brahmins, who saw

BACK/UP/NEXT

them as an unwanted threat to their Puritan

A LET'S GO CITY

DISCOVER BOSTON

hamlet on a hill. Although they spent much of the

ONCE IN BOSTON

20th century trying to curb the power of immigrant

BOS

LIFE & TIMES

groups, as the years wore on it was in non-

History

Brahmins---especially Irish Catholics---that the

17th Century: Pilgrims

city's social and political power was centered.

Buy from Glob

& Puritans

Amazon,

18th Century: the

Sensing defeat, when less-than-acceptable

or for you

American Revolution

neighbors finally began creeping up onto Beacon

Not logged in

19th Century: Boston

Hill, the Brahmins evacuated and headed for land

Brahmins

that was being created just for them. Although the

Rise of Boston

filling in of Back Bay (with land from the other 2 of

STA TRAVEL

Brahmins

the Shawmut Peninsula's 3 hills) had begun in the

Civil War & Abolition

great student

early 19th century, it did not start in earnest until

from

Post-War Boom

1858, when hundreds of thousands of loads of

Birth of the Back Bay

to

gravel from Needham were transported to the city

Athens of America

depart

and dumped into the festering swamp west of

date

Aug

Early 20th Century:

Downtown Boston. Nearly 4 decades later, Boston

return

Corrupt Politics

date

had gained over 400 acres and the entirely new

Late 20th Century: a

I am a student

City Reborn

neighborhoods of the Back Bay and the South

date of birth (m

21st Century: Building a

End. Moreover, the "First Families" gained a new

Modern Beantown

place for their mansions, filling the Back Bay with

Find far

Further Resources

luxurious palaces befitting their self-envisioned

ALTERNATIVES TO

regal status.

TOURISM

Book a t

Choose a country

Only in Let's Go: Boston:

Sights

Choose a cou

Food & Drink

Nightlife

Note: See Commonwealth

Sports & Entertainment

Shopping

Avenue file.

Arrival Date:

Accommodations

Number of

Daytrips From Boston

Nights:

Planning Your Trip

Service Directory

Powere

http://www.letsgo.com/BOS/03-LifeTimes-463

8/24/2004

Let's Go - Boston - Athens of America

Page 1 of 2

Home

Destinations

Bookstore

Resources

Forums

Features

BOSTON

LET'S GO

Boston / Life & Times / History / 19th

Century:Boston Brahmins / Athens of America

LET'S

Athens of America

Search Let's Go

Yet despite their snobbery and their eventual fall

from prominence, the Brahmins did leave a

BACK/UP /NEXT

significant legacy for the city of Boston, and did

A LET'S GO CITY

DISCOVER BOSTON

much to improve the quality of intellectual life

ONCE IN BOSTON

during their era of prominence. The time of the

BOST

LIFE & TIMES

"First Families" rule was one of great cultural and

History

artistic growth, centered mostly on the creation of

17th Century: Pilgrims

many important civic and cultural institutions in the

Buy from Glob

& Puritans

long-neglected Fenway area (where they remain

Amazon,

18th Century: the

to this day). Private donations from deep blue-

or for you

American Revolution

blood coffers provided most of the funding for

Not logged in

19th Century: Boston

such ventures as the Boston Public Library

Brahmins

(which doubles as an art museum), the world-

Rise of Boston

renowned Museum of Fine Arts (eventually

STA TRAVEL

Brahmins

Civil War & Abolition

moved to the Fenway from its original Copley Sq.

great student

location), the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and

from

Post-War Boom

the now-defunct Museum of Natural History, all

to

Birth of the Back Bay

built between 1840 and 1880. This influx of high

Athens of America

depart

Aug

culture and the city's propensity for fostering high-

date

Early 20th Century:

minded thinking earned Boston the nickname

return

Corrupt Politics

date

"Athens of America." Indeed, around this time,

Late 20th Century: a

I am a student

City Reborn

Mark Twain noted: "In New York, they ask 'How

date of birth (m

21st Century: Building a

much is he worth?" In Philadelphia, 'Who were his

Modern Beantown

parents?' In Boston, they ask 'How much does he

find for

Further Resources

know?"

ALTERNATIVES TO

TOURISM

Book a I

Choose a country

Only in Let's Go: Boston:

Sights

Choose a cou

Food & Drink

Nightlife

Arrival Date:

Sports & Entertainment

Shopping

Accommodations

Number of

Daytrips From Boston

Nights:

Planning Your Trip

Service Directory

Powere

http://www.letsgo.com/BOS/03-LifeTimes-465

8/24/2004

BostonFamilyHistory.com -- The Place to Meet Your Past

Page 1 of 6

Boston Family History.com

The Place to Meet Your Past

Home > Boston's Neighborhoods > Back Bay

Learn more about your ancestor's neighborhood through the timeline,

Home

find more information in the Further Reading section, or use the links

Immigrant

to experience life in that community today.

Boston

Neighborhood

History

Timeline

Walk Historic

Further Reading

Boston

Links

Plan a Trip

Genealogical

Resources

Timeline

Family History

for Kids

1600-1750: Back Bay is named as the Bay in the back of the

Guest Book

town. It is a tidal bay, and at low tide primarily tidal flats. Native

Search

American fish weirs in this area, off of what is now the Common,

Boston History

Collaborative

go back at least 1000 years. They were found during building

excavations for The New England on Boylston Street (between

Berkeley and Clarendon Streets.)

1775: British troops cross Back Bay on their way to Lexington

and Concord.

1821: Mill Dam runs from Beacon Street to Charles Street and

across to Sewellís Point, Brookline. The dam is the brainchild of

Uriah Cotting and the Roxbury Mill Corporation. The structure is

50 feet wide and one half mile long with a toll road running over

it between a row of trees. It is called Western Avenue and later

Beacon Street.

1825: Back Bay is annexed to Boston.

1827-1847: The city discharges raw sewage into the basin of

http://www.bostonfamilyhistory.com/neigh bbay.html

1/4/2005

BostonFamilyHistory.com -- The Place to Meet Your Past

Page 2 of 6

Mill Dam.

1837: The Public Garden opens. It is the idea of horticulturist

Horace Gray. The Garden is later redesigned by George

Meacham in 1859.

GBD'S

1850s: A second perpendicular dam is extended from Mill Dam

to Gravelley Point, Roxbury that divides the bay into two parts.

The Boston and Worcester and Boston and Providence Railroads

run across the marsh. Steam power and railroads combine to

accelerate the filling of Back Bay. However, the dam and

railroads disrupt the tides and combined with pollution make the

area a stagnant cesspool.

1857: Several contracts were awarded to fill in the Back Bay.

While some of the fill was given to the contractors, the rest was

taken by train from Needham.

1858: Arlington Street and Commonwealth Avenue Mall are laid

out. Arthur Gilman and Gridley J. Fox Bryant design a street plan

for Back Bay that is a grid. Streets are named for Massachusetts

towns from Arlington to Ipswich and arranged in alphabetical

order.

1859: Edward Clarke Cabot designs the Russell and Gibson

Houses on Beacon Street

1860: The Arlington Street Church is constructed and designed

by Arthur Gilman and Gridley J. F. Bryant. It is the oldest church

in Back Bay. By this time, Back Bay has been filled to Clarendon

Street.

1862: Emmanuel Church is designed by A.R. Estey on Newbury

Street.

1863: The initial buildings of Massachusetts Institute of

Technology (MIT) and the Museum of Natural History are built

side by side on Boylston Street. MIT is founded by William

Barton Rogers whose father Partick was an Irish immigrant who

http://www.bostonfamilyhistory.com/neigh1 bbay.html

1/4/2005

BostonFamilyHistory.com -- The Place to Meet Your Past

Page 3 of 6

fled to the United States after the failed Irish uprising of 1798.

Both MIT and the museum later moved.

1866: The Central Congregational Church is built on Berkeley

and Newbury.

1867: William Gibbons Preston (1842-1910) and Clemens

Herschelís (1842-1930) suspension bridge in the Garden is the

smallest of its kind in the world.

1868: The First Church (originally founded in 1632) is moved to

Berkeley and Marlborough Streets. That same year, William

Robert Ware establishes the first architecture school in the

United States at MIT.

1869: Thomas Ballís (1819-1911) statue of George Washington

is unveiled in the Public Garden. Patrick S. Gilmore hosts the

National Peace Jubilee in St. James Park to celebrate the end of

the Civil War. A 10,000 person chorus, 1,000 piece orchestra,

and 100 anvil percussion section played the Anvil Chorus of Il

Travatore as the finale.

1870: Oliver Wendell Holmesi (1809-1894) townhouse is built

on Beacon Street. It is now an apartment building. At this point,

Back Bay has been filled to Exeter Street.

1872: Thomas Paget takes visitors on the first swan boat ride in

the Garden. Park Square station is built by Peabody and Stearns

as a stop on the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad. It

is later demolished.

1872-1877: The Trinity Church is built in Copley Square.

1873: Brattle Square Church, designed by Henry H. Richardson,

is built on Commonwealth Avenue. The structure is constructed

on 4,500 wooden pilings that were sunk into the ground.

1876: The original Museum of Fine Arts opens in Copley Square

on the site where the Copley Plaza Hotel now stands (built

http://www.bostonfamilyhistory.com/neigh bbay.html

1/4/2005

BostonFamilyHistory.com -- The Place to Meet Your Past

Page 4 of 6

1911).

1879: The Trinity Church rectory is designed by Henry.H.

Richardson (1837-1886). Peabody and Stearns finish a

townhouse for John Phillips which is now the First Lutheran

Church of Boston on Marlborough Street.

1880: Emerson College of Oratory is founded. At this point,

Back Bay has been filled nearly to the mainland.

1881: The Harvard Medical School is built at Boylston and

Exeter Streets. The Prince School is built and named after Mayor

Frederick O. Prince (1818-1881).

1883: Copley Square is named after Beacon Hill artist John

Singleton Copley.

1884: Hollis Street Church is built. Edward Everett Hale (1822-

1909) is its pastor for many years as well as being the chaplain

of the United States Senate.

1893: A 100 foot promenade is extended into the Charles River.

1895: Mary Baker Eddyís first Christian Scientist Church in

Boston is built on Falmouth and Norway Streets. The Boston

Public Library opens at Copley Square.

1901: The Lenox Hotel, designed by Arthur Bowditch, is

constructed.

1905: William Lindsay (1858-1921), inventor of the ammunition

belt, commissions Chapman and Frazer to build him a mansion

on Bay State Road. Today, "The Castle" is owned by Boston

University.

1906: Charles Brigham designs the First Church of Christ,

Christian Scientist Church on Huntington Ave.

http://www.bostonfamilyhistory.com/neigh bbay.html

1/4/2005

NABB - History of Back Bay

Page 1 of 6

NABB

History of Back Bay

Select

Home

1814

Development begins: Mass legislature chartered the Boston and

Roxbury Mill Corporation, and approved construction of a long mill

What is NABB

dam to cut off 430 acres of tidal flats from the river, which also

Join NABB

served as a toll road to Watertown. The dam is under present-day

Beacon Street.

Current News Letters

1821

Basin subdivided into Upper or Fill Basin, Lower or Receiving

Committees

Basin, to power water mills

1828

70-75 Beacon Street built along the mill dam, oldest structures in

Friends and Neighbors

the Back Bay

Activities

1841

US Harbor Commission established line beyond which the Back

Resources for Residents

Bay could not be filled, and thus encroach on the harbor

History of Back Bay

1849

Health Department demanded the area be filled

Links

1850

152 Beacon Street built for Isabella Stewart by her father

1850

Contact Us

Mass appointed commission to investigate the Back Bay and

recommend development options

Site Map

1852

July -- Commission on Harbor and Back Bay Lands appointed

1853

Commissioners on Boston Harbor and Back Bay Lands begin

writing annual reports

1855

Name of Commission on Harbor and Back Bay Lands changed to

Commissioners on Public Lands

1856

Tripartite Agreement of 1856 between the State of Mass, Boston,

and the Boston and Roxbury Mill Corporation-dividing up the

lands. Part of the city land went to develop the Public Garden.

1857

September--Filling of the Back Bay began-average depth of fill

http://www.nabbonline.com/history.htm

1/4/2005

3/16/2016

Back Bay History I NABB Online

search

Neighborhood

Association

of

the

Back Bay

11

Home About Us Membership Committees Activities City Resources Links Contact Us

160 Commonwealth Ave

Back Bay History

Boston, MA 02116

Phone: (617) 247-3961.

Fax: (617) 247-3387.

For a genealogical history of Back Bay's houses - information about who lived in them and how

info@nabbonline.com

they were used over the decades - go to the website Back Bay Houses. Launched in 2014, the

website is the culmination of ten years of research to identify who lived in (and, if possible, who

About NABB

owned) each Back Bay property. All you have to do is click on a property's address to find out the

NABB's Officers and

names of the house's prior residents (including wives' unmarried names) and read a very high-

Directors

level summary of what they did in the world. Voilà - Your instant Back Bay ancestors!

Back Bay History

Timeline of the History of the Back Bay

NABB's Community

Service Awards

1814

Development begins: Massachusetts Legislature chartered the Boston and Roxbury

News

Mill Corporation, and approved construction of a long mill dam to cut off 430 acres of

Event Calendar

tidal flats from the river, which also served as a toll road to Watertown. The dam is

under present-day Beacon Street.

Donate

1821

Basin subdivided into Upper or Fill Basin, Lower or Receiving Basin, to power water

mills

1841

US Harbor Commission established line beyond which the Back Bay could not be

filled, and thus encroach on the harbor

1849

Health Department demanded the area be filled

1850

Commission appointed to investigate the Back Bay and recommend development

options

1852

July -- Commission on Harbor and Back Bay Lands appointed

1853

Commissioners on Boston Harbor and Back Bay Lands begin writing annual reports

1855

Name of Commission on Harbor and Back Bay Lands changed to Commissioners on

Public Lands

1856

Tripartite Agreement of 1856 between the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the City

of Boston, and the Boston and Roxbury Mill Corporation - dividing up the lands. Part

of the city land went to develop the Public Garden.

1857

September--Filling of the Back Bay began-average depth of fill 20 feet; more than

450 acres filled; fill brought from Needham; streets were filled to grade 17 (17 ft above

mean low tide), lots filled to grade 12, so basements would be below street level.

http://www.nabbonline.com/about_us/back_bay_history

1/4

3/16/2016

Back Bay History I NABB Online

Back Bay from the State House 1857

1859

The Unitarian congregation, then in a church on Federal Street designed by Charles

Bulfinch, votes to build a new building in the Back Bay at the corner of Arlington and

Boylston Streets.

1860

The house at 137 Beacon Street, later known as the Gibson House, was built

1860

152 Beacon Street built for Isabella Stewart by her father

1860

Filling of Back Bay reached Clarendon Street

1861

State granted a block of Back Bay (Boylston and Berkeley) to the Boston Society of

Natural History and MIT

1861

Halcyon Place (corner of Berkeley and Commonwealth) built as a guest home for

families of patients at Mass General

1861

The Unitarians' new church, now known as Arlington Street Church, is completed. It

is the first public building in the Back Bay.

1862

Emmanuel Church (15 Newbury Street), the first building constructed on Newbury

Street, is consecrated.

1863

MIT located on Boylston-current site of New England Life building

1864

Society of Natural History building completed (Berkeley between Boylston and

Newbury)

1865

December-Toll no longer collected on mill dam toll road

1865

First statue erected on the Commonwealth Avenue Mall

1867

Central Congregational Church completed (Newbury Street and Berkeley)

1868

First Church of 1630 (Unitarian) moved from Chauncy Place to newly completed

church designed by Ware and Van Brunt (Berkeley and Marlborough)

1869

Temporary coliseum built in Copley Square. It held the National Peace Jubilee that

year, which was attended by President Ulysses Grant

1870

Filling of Back Bay reached Exeter Street

1871

160 Commonwealth, Hotel Vendome, built--first hotel in city with electric lighting, it

had an independent lighting plant designed by Edison in 1882

1871

Brattle Square Church (Unitarian) moved to newly built church designed by H.H.

Richardson (Commonwealth and Clarendon) aka-"church of the holy bean blowers."

Statues on the tower designed by Frederic August Bartholdi, designer of the Statue of

Liberty.

1872

Fire destroys 65 acres of downtown Boston

http://www.nabbonline.com/about_us/back_bay_history

2/4

3/16/2016

Back Bay History I NABB Online

Commonwealth Ave in Process, 1872

1874

Second Church of 1660 (Unitarian) moved from Bedford Street to newly completed

church (Boylston between Dartmouth and Clarendon)

1875

Third Church (Congregational) moved from Old South Meeting Hall to newly

completed church (Dartmouth and Boylston)

1876

Museum of Fine Arts opened in Copley Square

1877

Trinity Church completed, designed by H.H. Richardson

1879

Commissioners on Public Lands changed to Harbor and Land Commission

1880

150 Beacon Street - Isabella Stewart Gardner bought to expand her home at 152

1880

Land for the current site of Boston Public Library purchased

1882

Filling of Back Bay complete to Charlesgate East

Ru

=

House on the Corner of Exeter and Marlborough

1883

Harvard Medical School located in building at Boylston and Exeter

1883

Triangle lot bounded by Huntington, Dartmouth, Boylston purchased and named

Copley Square

1884

Hollis Street Church completed (southeast corner of Newbury and Exeter, current site

of Exeter towers) It was destroyed in 1966

1884

Triangle lot bounded by Huntington, Trinity Place, St. James added to Copley Square

to make it a square

1885

Temple of the Working Union of Progressive Spiritualists completed (northeast corner

of Newbury and Exeter)

1887

Bridge from West Chester park in Boston to Mass Ave in Cambridge authorized

1889

Bay State Road created by dredging the river and filling the Charles Rivers

http://www.nabbonline.com/about_us/back_bay_history

3/4

3/16/2016

Back Bay History I NABB Online

1890

Filling of Back Bay reached Kenmore Square

1891

Bridge from West Chester Park in Boston to Mass Ave in Cambridge opened to

travel, and renamed the John Harvard bridge

1894

West Chester Park renamed Massachusetts Avenue

1895

Boston Public Library opened in Copley Square

1895

Christian Science Church dedicated

1899

Mass Historical society moved from 30 Tremont Street to the newly built 1154

Boylston Street

1900

Filling of Back Bay completed with last few acres of the Fens

1908

Last single-family residence built on an originally vacant lot in the residential district

at 530 Beacon Street

1910

MIT moved to Cambridge

Aerial View of Back Bay, 1925

1955

Neighborhood Association of the Back Bay formed

1963-

Magnolias planted on Commonwealth Avenue

1965

1966

Massachusetts Legislature establishes the Back Bay Architectural District

1967

Back Bay Architectural Commission holds its first meeting

1969

20 Gloucester Street - First conversion of an existing residental building to

condominium units in the City of Boston

1973

Back Bay added to the National Registry of Historic Places

Images provided courtesy of the Boston Public Library. To see more historic images,

please visit the BPL's digital image gallery.

NABB

160 Commonwealth Ave, suite L-8

Boston, MA 02116

Tel: (617) 247-3961

info@nabbonline.com

Copyright © 2016 Neighborhood Association of the Back Bay. All rights reserved.

Banner photos copyright © 2008 Penny Cherubino. All rights reserved.

Web site design and development by Digital Loom - Boston, MA

http://www.nabbonline.com/about_us/back_bay_history

4/4

NABB - History of Back Bay

Page 2 of 6

20 feet; more than 450 acres filled; fill brought from Needham;

streets were filled to grade 17 (17 ft above mean low tide), lots

filled to grade 12, so basements would be below street level.

Back Bay from the State House 1857

1859

Arlington Street Church built

1860

The house at 137 Beacon Street, later known as the Gibson House,

was built

1860

Filling of Back Bay reached Clarendon Street

1861

State granted a block of Back Bay (Boylston and Berkeley) to the

Boston Society of Natural History and MIT

1861

Halcyon Place (corner of Berkeley and Commonwealth) built as

a

guest home for families of patients at Mass General

1862

152 Beacon Street-Isabella Stewart Gardner moved in

1862

Emmanuel Church completed (Newbury Street)

1863

MIT located on Boylston-current site of New England Life building

1864

Society of Natural History building completed (Berkeley between

Boylston and Newbury)

1865

December-Toll no longer collected on mill dam toll road

1865

First statue erected on the Commonwealth Avenue Mall (also see

http://www.nabbonline.com/history.htm

1/4/2005

NABB - History of Back Bay

Page 3 of 6

Mall statues)

1867

Central Congregational Church completed (Newbury Street and

Berkeley)

1868

First Church of 1630 (Unitarian) moved from Chauncey Place to

newly completed church designed by Ware and Van Brunt

(Berkeley and Marlborough)

1869

Temporary coliseum built in Copley Square. It held the National

Peace Jubilee that year, which was attended by President Ulysses

Grant

1870

Filling of Back Bay reached Exeter Street

1871

160 Commonwealth, Hotel Vendome, built-first hotel in city with

electric lighting, it had an independent lighting plant designed by

Edison in 1882

1871

Brattle Square Church (Unitarian) moved to newly built church

designed by H.H. Richardson (Commonwealth and Clarendon) aka-

"church of the holy bean blowers." Statues on the tower designed

by Frederic August Bartholdi, designer of the Statue of Liberty.

1872

Fire destroys 65 acres of downtown Boston

Commonwealth Ave in Process, 1872

1874

Second Church of 1660 (Unitarian) moved from Bedford Street to

http://www.nabbonline.com/history.htm

1/4/2005

NABB - History of Back Bay

Page 4 of 6

newly completed church (Boylston between Dartmouth and

Clarendon)

1875

Third Church (Congregational) moved from Old South Meeting Hall

to newly completed church (Dartmouth and Boylston)

1876

Museum of Fine Arts opened in Copley Square

1877

Trinity Church completed, designed by H.H. Richardson

1879

Commissioners on Public Lands changed to Harbor and Land

Commission

1880

150 Beacon Street-Isabella Stewart Gardner bought to expand her

home at 152

1880

Land for the current site of Boston Public Library purchased

1882

Filling of Back Bay complete to Charlesgate East

House on Marlborough & Fairfield

1883

Harvard Medical School located in building at Boylston and Exeter

1883

Triangle lot bounded by Huntington, Dartmouth, Boylston

purchased and named Copley Square

1884

Hollis Street Church completed (southeast corner of Newbury and

Exeter, current site of Exeter towers) It was destroyed in 1966

http://www.nabbonline.com/history.htm

1/4/2005

NABB - History of Back Bay

Page 5 of 6

1884

Triangle lot bounded by Huntington, Trinity Place, St. James added

to Copley Square to make it a square

1885

Temple of the Working Union of Progressive Spiritualists

completed (northeast corner of Newbury and Exeter)

1887

Bridge from West Chester park in Boston to Mass Ave in

Cambridge authorized

1889

Bay State Road created by dredging the river and filling the

Charles Rivers

1890

Filling of back bay reached Kenmore Square

1891

Bridge from West Chester Park in Boston to Mass Ave in

Cambridge opened to travel, and renamed the John Harvard

bridge

1894

West Chester Park renamed Massachusetts Avenue

1895

Boston Public Library opened in Copley Square

1895

Christian Science Church dedicated

1899

Mass Historical society moved from 30 Tremont Street to the

newly built 1154 Boylston Street

1900

Filling of Back Bay completed with last few acres of the

Fens

1904

5 Commonwealth Ave built by Walter C. Baylies; 1912 built

ballroom for daughter's debut. Building now houses the Boston

Center for Adult Education.

1910

MIT moved to Cambridge

http://www.nabbonline.com/history.htm

1/4/2005

8/10/2021

Overview: Development of the Back Bay I Back Bay Houses

Back Bay Houses

Genealogies of Back Bay Houses

Overview: Development of the Back Bay

Overview - 1855-1859 - 1860-1864 - 1865-1869 - 1870-1874 - 1875-1879 - 1880-1884 - 1885-1889

- 1890-1899 - 1900-1909 - 1910-2015

The Back Bay neighborhood of Boston is built almost entirely on filled (or "made") land,

replacing what originally was a relatively shallow bay and tide lands. Transforming this

area to land which could be used for building purposes took several decades and rep-

resented one of the largest landfill operations in the 19th Century.

A number of excellent books and articles have been written on the filling of the Back

Bay. Walter Muir Whitehill's Boston, A Topographical History and Bainbridge Bunting's

Houses of Boston's Back Bay provide overviews. More comprehensive information is

included in Nancy S. Seasholes's Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston,

which discusses the Back Bay project in the context of Boston's overall land fill develop-

ment, in Boston's Back Bay by William A. Newman and Wilfred E. Holton, which is de-

voted exclusively to the filling of the Back Bay, and in Karl Haglund's Inventing the

Charles River, which examines the evolution of the Charles River, including the

Esplanade. These books contain excellent maps showing the progress of the filling op-

erations, many based on the early blueprint maps prepared in 1881 by Fuller and Whit-

ney, civil engineers associated with the project, in their A Set of Plans Showing the Back

Bay 1814-1881.

https://backbayhouses.org/overview-development-of-the-back-bay/

1/22

8/10/2021

Overview: Development of the Back Bay I Back Bay Houses

The development of the Back Bay began as a water power project. In 1814, the Boston

and Roxbury Mill Corporation was authorized by the Massachusetts legislature to build

a dam from the corner of Charles and Beacon Streets in the east to Sewall's Point in the

west (at that time in Brookline; what is today Kenmore Square in Boston), separating

about 430 acres of tidal lands from the Charles River. A Cross Dam was built connect-

ing with the Mill Dam at a point about 210 feet west of what is today Hereford and run-

ning southwest at approximately a 45 degree angle to Gravelly Point (at about what is

today the intersection of Commonwealth and Massachusetts Avenues). The Cross Dam

divided the tidal lands into two basins. A western basin (about where the Fenway

neighborhood is today), called the Full Basin, and an eastern basin (about where the

Back Bay neighborhood is today), called the Receiving Basin. Water was allowed to

flow into the Full Basin from the river at high tide, then into the Receiving Basin and

then back into the river at low tide. The tidal flows were used to power mills located

along the Cross Dam. A toll road was built on top of the dam and is today's Beacon

Street. The project was completed in 1821 and was not highly successful.

In 1834, the legislature permit-

ted construction of two railroad

causeways that formed an "x"

across the Receiving Basin.

These impeded the tidal flows

and made the mill operations

even less productive. In addi-

tion, sewage was allowed to

flow freely into the basins and,

over time, the area became odi-

ferous and unhealthy. At the

same time, Boston's population

was growing and more land was

needed to accommodate that

Detail from an 1853 map of the City of Boston by George

W, Boynton, courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map

growth. As Nancy S. Seasholes's

Center at the Boston Public Library.

Gaining Ground discusses in de-

tail, the city had historically grown by filling land, and the Back Bay presented an oppor-

tunity to eliminate a health hazard while meeting an economic need.

https://backbayhouses.org/overview-development-of-the-back-bay/

2/22

8/10/2021

Overview: Development of the Back Bay I Back Bay Houses

The map at the right, detail from an 1853 map by George W. Boynton, shows the Back

Bay as it existed in 1853, with the extension of Beacon Street along the mill dam re-

ferred to as Western Avenue.

The photograph below shows this area in a panoramic view taken from the Massachu-

setts State House ca. 1858. The Mill Dam appears on the right, running west towards

Brookline, with the Cross Dam running south to Gravelly Point. The Boston and

Worcester Railroad and Boston and Providence Railroad lines cross at the center of the

Receiving Basin.

Photograph looking west and southwest from the Boston State House, attributed to Southworth &

Hawes (ca. 1858); courtesy of the Boston Athenaeum

In 1850, the Massachusetts Legislature appointed three Commissioners to investigate

the ownership of the tidal flats in the Back Bay and "consider what measures can be

taken for the improvement of the said flats of land, so as to make them most valuable

to all parties interested therein" (Chapter 111, Resolves of 1850 and Chapter 80, Re-

solves of 1851). The Commissioners presented their report in March of 1852, recom-

mending that the Commonwealth should "authorize the parties of interest to change

the use of the receiving basin from mill purposes to land purposes, and fill up the

same," and suggested specific steps that the Commonwealth should take towards that

end.

That same month, the legislature (Chapter 79, Resolves of 1852) established a perman-

ent three member board of commissioners to implement the previous commissioners'

recommendations. The Commissioners on Boston Harbor and the Back Bay (renamed

the Commissioners on the Back Bay in 1855; Chapter 388, Acts of 1855) were charged

with the authority "to determine and settle, by agreement, arbitration or process of

https://backbayhouses.org/overview-development-of-the-back-bay/

3/22

Back Bay Patrons

by Walter Muir Whitehill

When the Museum of Fine Arts was incorporated in 1870, the

Back Bay was only ten years old. Four out of the twelve Founders,

however, had already moved to the new region, although six still

lived around Beacon Hill, and two outside the city limits of Boston.

The transformation of the Back Bay from water to land was part

of a process of topographical change by which Bostonians, almost

from the moment of settlement in 1630, had been tinkering with

their landscape in an effort to accommodate an expanding pop-

ulation on the small water-ringed peninsula that had been chosen

for a wilderness village. In the seventeenth and eighteenth cen-

turies, when Boston was a compact British seaport, nearly every-

one lived close to the harbor, in the North End or the old South

End (the present department store district). Only after the build-

ing of the present State House in 1795, on the southern slope of

Beacon Hill, did the adjacent upland fields and the streets facing

Boston Common rapidly become a new residential district that

bore the architectural mark of the style of Charles Bulfinch.

In 1800 Boston was still a relatively simple, compact, and

homogeneous seaport with only 24,397 inhabitants. Its great

expansion, which was to come throughout the nineteenth century,

was SO enormous that by 1900, through waves of immigration

rolling in from Europe, Boston was a city of 560,892 inhabitants. As

the town grew, SO did its wealth. The China Trade gave nineteenth

century Boston a running start on prosperity. More money was

made in manufacturing and mercantile pursuits. Textile mills

proliferated around New England, but the capital and initiative

came from Boston, where the owners generally lived. As the cen-

tury progressed, capital gained in maritime commerce would

often be plowed not only into textile manufacturing but into the

development of railroads, mines, and land far beyond the confines

of New England. This growth in people and prosperity produced

an acute shortage of space. Thus in 1856 steps were begun to obtain

more land through the filling of the Back Bay.

Bostonians had always had a special affection for Paris, pos-

sibly because of lingering anglophobia from two wars with

England. The design of Commonwealth Avenue and other Back

Bay streets reflected the spaciousness of Baron Haussmann's new

Paris boulevards just as the new City Hall, built on School Street

during the Civil War, mirrored the architectural style of the

French Second Empire. So for that matter did the mansard roofs

86

of many Back Bay houses. By the filling of the Back Bay a hand-

some new residential district was created to replace the older

ones that were being encroached upon by business and by the

burgeoning slums.

As Franklin and Summer Streets, Temple Place, Tremont

Street, Park Street, and Pemberton Square were taken over by

business, many families built houses in the new Back Bay. John

Lowell Gardner, for example, whose family lived at the corner of

Beacon and Somerset Streets, moved to a newly built brownstone

house at 152 Beacon Street when he married Isabella Stewart of

New York in 1860. The fashion he set was eagerly followed. Dr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes reflected the general feeling when, mov-

ing to 296 Beacon Street a decade later, he announced that he

was "committing justifiable domicide."

The Bostonians who migrated to the Back Bay left none of

their traditions or characteristics behind them. Indeed they throve

even more vigorously on "the flat" of the Back Bay streets. The

proceeds of their diligence, whether in maritime commerce, man-

ufacturing, banking, or investment, continued to support Harvard

College and to found and nurture an extraordinary galaxy of

institutions, learned and benevolent, humanistic and scientific,

that make Boston and its Back Bay a center of civilization. A

transplanted English editor, E. L. Godkin, observed in 1871 that

"Boston is the one place in America where wealth and knowledge

of how to use it are apt to coincide."

Back Bay was a particular coincidence. Almost as soon as the

people came, the churches faithfully followed. The Unitarians of

the Federal Street Church, over which William Ellery Channing

had presided from 1803 to 1842, began to build in 1859, at the

corner of Arlington and Boylston Streets, the present Arlington

Street Church. The First Church bought land on the corner of

Berkeley and Marlborough Streets in 1865, and occupied a new

Ware and Van Brunt Gothic church there in 1868. On the periph-

eries of what became in 1883 Copley Square, the Third (or Old

South) Church bought land in 1869, Trinity Church in 1871, and

the Second Church in 1872.

The Back Bay Bostonians not only brought along their old

institutions; they founded new ones. From the Legislature in the

winter of 1860-1861 the Boston Society of Natural History, or-

ganized in 1830, received a grant of land on Berkeley Street (ex-

87

tending from Boylston to Newbury); on this site it soon built the

forerunner of today's Science Museum, which now houses Bonwit

Teller's shop. The remainder of this block was devoted to the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, incorporated in 1861 and

now located across the Charles River in Cambridge. Here was

formed the first school of architecture in the United States, and

here the Lowell Institute's public lectures were given, watched

over by Augustus Lowell, who lived conveniently nearby at 171

Commonwealth Avenue. Almost next door to him, at 191 Com-

monwealth, Henry Lee Higginson watched over the Boston Sym-

phony Orchestra, which he founded in 1881. The early presence

of these institutions begat others. The newly incorporated Museum

of Fine Arts was awarded by the City on May 26, 1870 a plot of

land at the corner of Dartmouth Street and St. James Avenue that

had been given in trust by the Boston Water Power Company

(the previous owner of part of the Back Bay), to be used either

for an Institute of Fine Arts or for an open square. Nearby, the

Harvard Medical School moved in 1883 to a new building at

Boylston and Exeter Streets, while in 1888 the cornerstone was

laid for the adjacent building of the Boston Public Library, which

was first opened to readers in 1895.

Institutions begin as ideas in the mind of man. They are sus-

tained successfully only if that mind is tenacious as well as

intelligent. This is in the Boston tradition. The Boston Athenaeum,

a proprietory library incorporated in 1807, grew out of a dining

club organized in 1804 by a typical Boston mixture of clergymen,

lawyers, physicians, and merchants who were also literary en-

thusiasts. This happy ambivalence is nowhere better illustrated

than in the case of the Massachusetts Historical Society and the

Provident Institution for Savings, which from 1833 to 1856 shared

a building at 30 Tremont Street; there James Savage, an officer

of both, would happily run up and down stairs as he turned from

receiving deposits to editing historical documents. His parallel is

to be found again and again in the Back Bay: Edward Jackson

Holmes, who on the left hand was a lawyer, and on the right

hand, Acting Director and then President of the Museum; Charles

Goddard Weld, who trained as a doctor and who was one of the

greatest benefactors of the Museum's Asiatic Department; or

Henry Lee Higginson, stockbroker and music maker.

These and other Back Bay residents gave an extraordinary

88

amount of their skill, thought, and leisure to the disinterested

service of cultural and charitable institutions, and such institu-

tions have benefited extraordinarily from their generosity. This

blending of scholars with an endlessly renewable supply of literate

and responsible Trustees and treasurers has done more than

anything else to make Boston a center of civilization, or, in Alfred

North Whitehead's more affectionate view, to place Boston in a

position comparable to that occupied by Paris in the Middle Ages.

By 1900 almost every lot in the Back Bay had been completely

built upon from Arlington Street west to Massachusetts Avenue,

and from the Charles River south to Boylston Street. In the early

years of the twentieth century, the pattern of the Back Bay was

extended further to the westward along the Charles River in Bay

State Road (laid out in 1889), and to the southwest in the Fenway,

the road bordering the Muddy River and the Back Bay Fens, de-

signed in the eighties by Frederick Law Olmsted to link in a con-

tinuous green area the Public Garden and Commonwealth Avenue

with Franklin Park in West Roxbury. These extensions were over-

ambitious, for neither of them were ever completely built up with

private houses as originally envisioned. But the Back Bay from

Arlington Street to Charlesgate was a singularly unified and

handsome area. Although its houses were mostly built by indi-

vidual owners using a variety of architects, the observance of

setbacks and height limits gave an architectural unity to the

blocks. Commonwealth Avenue in the days of horse-drawn car-

riages and sleighs was a distinguished boulevard that can hardly

be imagined with today's ubiquity of automobiles, parked and

in motion.

Form followed function in the houses of the Back Bay. The

almost universal plan called for a downstairs reception room

where those not on intimate terms with the family were received.

The upstairs library or reception room was used to greet friends

and relatives. This could also serve as an office for the head of

the household, for he might come home at noon for lunch, and

afterward work on his figures under his own roof. The alleys

between the houses served as routes for tradesmen and gave

access to the back doors. Goods and victuals were delivered, a

reason why there were no shops or stores in the original Back Bay;

even today they appear only on the periphery of the major resi-

dential streets. The Back Bay was socially homogeneous, for many

89

residents would be only a block or two away from the majority

of their sisters and their cousins and their aunts. In the summer

the region was deserted, for a substantial resident would have

one if not two country houses outside the city. The Spaulding

brothers of 99 Beacon Street had a house at Prides Crossing on

the North Shore, which was in tolerable reach by train, but some

of their neighbors who summered in Maine might also have a

house in Brookline, Chestnut Hill, or Readville for spring and fall.

Between domestic moves, the Back Bay Bostonians traveled.

They visited London, Paris, and Rome; they journeyed to the Near

and the Far East. Frequently, the fruits of their travels appeared

first as loans and then as gifts to the Museum. Diligence was also

apparent here, for they collected, often ahead of anyone else,

works of rare beauty and importance. At home they encouraged,

used, and bought works of their contemporaries. John Singer

Sargent came to their houses as a welcome guest, as their court

painter, and as the decorator of their public buildings. John

La Farge made his stained glass windows for them; Augustus Saint

Gaudens sculpted their monuments and their heroes. They

painted like Edward Boit of 176 Beacon Street, who was accom-

plished enough to hold joint watercolor exhibitions with Sargent,

and to sell out almost as fast. They pursued hobbies like Mrs. J.

Montgomery Sears, who turned the attic of her Arlington Street

house into a photographic studio and library. They held musi-

cales, like Mrs. John L. Gardner and Mrs. Sears. They gave en-

couragement to the arts not only by general support but by such

specific generosities as Edward Boit's traveling scholarships for

the Museum School, or Benjamin Smith Rotch's architectural

fellowships, established in 1883, which have provided foreign

travel for such contemporaries as Edward D. Stone, Walter F.

Bogner, Wallace K. Harrison, Gordon Bunshaft, and Louis

Skidmore.

There were few places in this Back Bay world for large public

gatherings, for Bostonians have always liked the intimacy of

private houses. Eighteenth-century visitors to Boston noted that

social clubs met in members' houses, rather than taverns or

places of public entertainment. When Boston clubs in the nine-

teenth century began to acquire permanent premises, they tried

to keep them as much like private houses as possible. The only

places in Boston where one of Peter Arno's well-stuffed "club

90

men" would feel that he had elbow room are the Algonquin Club,

built in 1887 by McKim, Mead and White, and the Harvard Club

of 1913, both on Commonwealth Avenue. The St. Botolph, Chilton,

and College Clubs in the Back Bay occupy converted dwellings,

as the Somerset, Union, Tavern, Odd Volumes, and Women's City

Clubs do in other parts of Boston. All attempt to maintain the

illusion of the private house.

Just as the Museum of Fine Arts migrated from Copley Square

to Huntington Avenue and the Fenway in 1909, most of the private

residents of the Back Bay have decamped. As the automobile

altered living habits, and as domestic service vanished, fewer

and fewer of the largest private houses continued to be occupied

in the manner for which they were built. Some have become

apartments; others, offices, schools, or, at the worst, rooming

houses. But the tide is turning, and as Beacon Hill houses have

become increasingly difficult to find, or afford, the prospects of

the Back Bay seem brighter. But whatever alterations may have

been made within, a sufficient portion of the Back Bay has sur-

vived to present a coherent picture of American architecture of

the second half of the nineteenth century that cannot be matched

elsewhere in the United States. Because the Back Bay is an

architectural harmony that deserves respect and preservation,

the Museum of Fine Arts on its centenary arranges this exhibi-

tion as a tribute and as a timely warning. The pages that follow

endeavor to show how certain residents played decisive roles in

molding the Back Bay and in making the Museum what it is today.

Walter Muir Whitehill

91

50

€

Boston's Back Bay : The story of Americas gred test 19th Centery handfill Project

neighborhood for many decades to come. Attracting some of the most

prestigious Protestant churches and important cultural institutions to

CHAPTER 3 BostoniNortheatum U.P., 2006.

the Back Bay would keep many wealthy Protestant families in Boston.

D

Pollution, overcrowding, and a desire to keep wealthy Protestants in

William A. Newman

Boston were three compelling reasons for filling the Back Bay. While

these motivations generated interest in creating the new neighborhood,

Wilfaed E. Holton.

carrying out such a massive project would be possible only if political

and financial considerations could be worked through by several gov-

Planning and Financing

ernments and business interests. Leaders faced the challenge of making

real the dream of a new, elegant neighborhood to replace a badly pol-

the Back Bay Landfill

luted former tidal marsh. Planning for filling the Back Bay would start

in 1852 and the complex project would begin in 1858.

Filling parts of the Back Bay began to be considered soon after the tidal

110

power project was completed in 1822. Several early plans and false starts

were motivated by the increasing pollution and crowding as Boston's

population grew. The various unrealized ideas for filling in the Back Bay

reflected key considerations that would remain strong when the Back

Bay Receiving Basin was finally filled, starting in 1858. Objections that

were raised to some plans revealed concerns that would later shape plan-

ning for a new, elegant neighborhood. Making the Back Bay project hap-

pen required getting through bitter conflicts among several government

groups and private parties: the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the

cities of Boston and Roxbury, the Boston Water Power Company, and in-

dividual landowners and planners. In the end, the State Commission

would be the most powerful player in pushing the project through to

successful completion.

Early, Unsuccessful Plans

In 1824 a plan was proposed to fill and subdivide the area west of Charles

Street, just west of the Boston Common beyond Charles Street (see fig.

3.1). As described by its promoters, the plan called for an elegant devel-

FIGURE 5.13. View of Commonwealth Avenue. This photograph, apparently taken from

opment with 321 house lots, spacious streets, and squares. 1 Five streets,

the church tower at the corner of Clarendon Street and Commonwealth Avenue, shows

each one block long, would run parallel to Beacon Street (the Mill Dam)

the view to the west in 1872. Most houses have been completed in the block between

Clarendon and Dartmouth Streets. The corner lots at Dartmouth Street lie six feet below

and stop near the edge of the Eastern Channel in the Receiving Basin.

the street level, illustrating the waffle pattern that was created when the middles of resi-

The City of Boston committee appointed to investigate this plan feared

dential blocks were left unfilled. Building construction had yet to occur on Common-

that the new area would not attract wealthy buyers and instead would

wealth Avenue west of Exeter Street. (Boston Athenaum.)

FRAMINGHAM STATE COLLEGE

10

Boston's Back Bay

Why Fill the Back Bay? 47

"social psychology" factor in the "Ecosystem Model" for understanding

prejudices brought from England. The neighborhoods with the highest

regional change. The values and desires of powerful groups in Boston

percentages of Irish residents in 1850 were the Commercial District and

shaped the project in fundamental ways. The other factors in Duncan's

the old South End (62.6 percent), the North End (42.7 percent), South

ecosystem model are population, organization, environment, and tech-

Cove (42.5 percent), South Boston (42.1 percent), East Boston and the Is-

nology all important elements in the filling of Boston's Back Bay.

lands (40.9 percent), and Haymarket and the West End (40.4 percent).

Chickering then considered the causes of the recent decline in the

"American," or native-born, population. He estimated that two thousand

Social Concerns Leading to Filling the Back Bay

men had gone to California from Boston in the past year, lured by "that

golden expedition," the gold rush. That emigration was of little concern

Planning for the new Back Bay strongly emphasized keeping as many

to Chickering, however, compared with the much larger number who

wealthy families in Boston as possible. In the 1850s nearly all Boston's

had moved to the suburbs of Boston. He noted the impact of commut-

high income families were Protestant and their primary breadwinners

ing by train, showing that many "merchants and others doing business

were businessmen and professionals who worked in downtown Boston.

in the City" had recently moved to neighboring towns and could com-

Understanding social motivations in planning for the Back Bay proj-

mute to their downtown jobs "as quickly and cheaply as if they had con-

ect requires looking at the demographic and social changes revealed in

tinued in their former residences." Chickering estimated that twenty

the 1850 and 1855 census data and examining the reactions of commu-

thousand people were commuting to Boston by train daily in 1850. 66

nity leaders to those changes. Dr. Jesse Chickering's special report in

The railroad commuters were well-to-do Protestants who had moved

1850, discussed above, was commissioned by the city to investigate "some

out of Boston-pushed out by crowded conditions in the city and the

facts and considerations relating to the foreign population among us, and

influx of poor Irish immigrants, and attracted to the suburbs by avail-

especially

in

the City of Boston. "62 Although the possibility of filling the

able land, large houses, and efficient transportation. This emerging sub-

Back Bay is not mentioned in Chickering's report, he indicated clearly

urban movement of high-income Protestant families threatened to in-

the need to keep native-born residents in the city so the "foreign class"

crease rapidly the relative population of Irish Catholic immigrants. It is

would not completely dominate Boston.

clear that Chickering feared this trend would continue and he felt that

Between 1845 and 1850 Boston's population grew from 114,366 to

Boston's character would change for the worse.

136,881, and the "foreign portion" (including children of foreign-born

The considerations of ethnicity, religion, and class were very impor-

parents) increased from 32.6 percent to 45.7 percent, nearing half of

tant to the established "American" group, which was indeed losing the

Boston's population. Most remarkably, the "foreign" population had

light grip it had held on Boston's politics and culture for more than two

grown by 70.2 percent in five years' time, while the "American" portion

hundred years. Until the early decades of the nineteenth century, English-

had decreased by 2.3 percent. Chickering stated that "most of this foreign

descendant families who could trace their residence in Boston and New

population are Irish

mostly poor, downtrodden and uneducated."

England from the seventeenth century had dominated Boston at all lev-

He did note that, while these immigrants required charity, they tolerated

els of the social structure. Chickering did hold out some hope for re-

their "trials" well and made their "scanty means" go as far as possible. 63

taining the elite Protestants of English origin, whom he clearly valued

Chickering was concerned that a large majority of the children in pub-

and wanted to keep in Boston. 67 As he wrote, the South End develop-

li primary schools were "foreign" children. These young people would

ment was beginning to hold some wealthy Protestant families in the city.

soon become adults, gain citizenship, and form a large voting bloc. 44

Social motivations for the Back Bay project centered on providing hous-

In 1850 large portions of the populations in several Boston neighbor-

ing for this group in Boston, and on giving them ample social and cul-

hoods consisted of "foreigners"-foreign-born people and their chil-

tural reasons to remain in the city.

dren. Fully 83.4 percent of this group originated in Ireland, and their

George Adams's report on the 1850 Boston census stressed the need to

Catholic religion was hated and feared by many Protestants because of

give wealthy people who might move to the suburbs more reasons to

48

Boston's Back Bay

Why Fill the Back Bay?

49

stay in Boston. He noted that the city already provided ample water

English Puritans dating from Boston's seventeenth-century origins. This

piped from Lake Cochituate in Framingham and operated good public

reflects the growing anti-immigrant sentiments of the time.

schools. Adams went on to say that, even without landfill for residential

Keeping much of the influential wealthy Protestant group in Boston

areas, Boston had the potential to double its population by developing

promised at least to postpone the time when Irish Catholic immigrants

East Boston and South Boston, but he overlooked the fact that those

would dominate the political power of the city. Creating the Back Bay as

neighborhoods were too far from downtown Boston to be convenient

an attractive, exclusive neighborhood close to downtown offices, Beacon

for

"the business class." A filled Back Bay would be an ideal location,

Hill, and the new Public Garden gave promise of maintaining the "Old

essentially an extension of the prestigious Beacon Hill neighborhood

Yankee" character of Boston. Though Curtis does not mention the plan-

and near the workplaces of many wealthy Protestants.

ning for the Back Bay project, which was then under way, it was clearly

The population of immigrants and their children increased at a slowed

designed to keep wealthy Protestants in Boston.

rate of 34.7 percent between 1850 and 1855. In the same period the "Amer-

Curtis also commented favorably on efforts by Governor Henry J.

ican" population barely held its own, increasing by only 0.8 percent. The

Gardner of Massachusetts to reduce the influx of undesirable immi-

net result of these changes was that the "foreign" population grew to rep-

grants. 75 Gardner was swept into office in 1854 by the astounding success

resent 53.0 percent of Boston's residents in 1855. 69 Curtis concluded, with

of the American Party in Massachusetts. 76 This political party, organized

a tinge of dread, that it was unlikely that, in the foreseeable future, "na-

through secret lodges of Protestant men in towns and cities, attacked the

live" Americans would again constitute a majority of Boston's popula-

ineffectiveness of existing parties and the corruption of politicians, and

tion.70 Boston would be a largely Catholic city and the Protestants' views

it claimed to champion the interests of common citizens-meaning

of the Catholic religion were very negative in the mid-nineteenth cen-

native-born Americans, excluding American Indians. The members of

lury, based on fears carried from Protestant Europe. This was the time

the American Party were called "Know-Nothings" by their opponents and

when "no Irish need apply" was a common discriminatory phrase in job

the press because they would not reveal anything about the workings of

listings in Massachusetts.

their organization. The American Party's power in Massachusetts coin-

In 1855, 80.2 percent of the immigrant group had Irish origins, and the

cided exactly with the planning of the Back Bay landfill project: the final

political implications of the growing "foreign" population were not lost

plan of the State Commission was approved in 1856. The anti-immigra-

on Curtis. 71 He emphasized that "native" American voters had increased

tion ideology of this political party seems to have influenced the strong

only 30.38 percent since 1850, but the number of "foreign" voters had al-

efforts of the commission on the Back Bay and the state legislature to at-

most tripled-a 194.64 percent increase. Curtis also pointed out that

tract wealthy Protestant families to the new Back Bay neighborhood.7 77

"il very large number of those who do business in Boston reside out of

Governor Gardner was reelected in 1855 and 1856 by smaller margins,

town with their families and households (estimated at 40,000). 72 This

but the American Party was weakened when Gardner took control from

represents doubling in railroad commuting from the 20,000 daily com-

the secret lodges because the members distrusted authority. In his 1856

muters estimated by Chickering only five years earlier.

inaugural address, Gardner announced that he would not run for re-

Curtis expressed concern about the 200 percent higher birthrate in

election and continued to stress the dangers of immigration and the role

the "foreign" population in Boston than in the "native" population since

of the "horde of foreign born" in the growth of the Democratic Party. 78

1850.7 The projected impacts on the public schools and on the future

Although the "Know-Nothings" lost power quickly, the desire of the State

political balance of power were of deep concern to the established "Amer-

government and other leaders to attract wealthy Protestants to the Back

ican" population in Boston. Curtis wrote that "the native inhabitants"

Bay continued unabated.

should "guard with patriotic care the glorious institutions bequeathed

The planning for the new Back Bay would soon demonstrate an em-

by il noble ancestry"; he concluded that proper efforts should be made

phasis on this desire. The layout of streets, avenues, and parks would cre-

to maintain a large majority of native-born citizens in Boston. 74 The

ate an elite neighborhood. Zoning restrictions and measures taken to

"glorious institutions bequeathed by a noble ancestry" were the legacy of

keep the prices of house lots high would maintain the high status of the

08

Boston's Back Bay

Planning and Financing the Back Bay Landfill O 69

the City of Roxbury over seventy-two acres of land between the new city

As the planning stage concluded and the filling process neared, an im-

line and Gravelly Point (see fig. 2.4). 49

portant decision was made that would increase the success of the new

The commissioners favored an elegant but simple plan with wide

Back Bay neighborhood. It would have been easier to start the filling at

streets in rectangular blocks. The successful plan of 1856 is generally cred-

the western end of the State's land, near Exeter Street, because the gravel

ited to the architect Arthur Gilman, assisted by another architect and

trains would not have to go as far or to cross from the Boston and Worces-

two landscape gardeners. 50 Mona Domosh tells us that Gilman's plan for

ter onto the Boston and Providence tracks before swinging onto the

the Back Bay was based on English precedents. She says that Gilman vis-

marshland. But that approach would have created the first new land in

ited London, where several of the city's most famous architects showed

the middle of the polluted area, isolated completely from other residen-

him the sights. He saw the new grand boulevards in London's West End,

tial neighborhoods. The land would not have been in demand because

particularly in Bayswater (north of Hyde Park) and Kensington (south

of its bad location. Instead, the plan was set to begin filling at Arlington

and west of the park). 51

Street on the State's land and to proceed westward block by block. In this

Social motives are clear in the commissioners' description of how

way the first land would lie near the wealthy and well-established Bea-

they developed the final plan. They listened attentively to the sugges-

con Hill neighborhood, the new Public Garden, Boston Common, and

tions of several "gentlemen of taste and judgment" who planned to pur-

downtown businesses, making it much easier to attract high-income

chase lots in the new neighborhood when it was filled. 52 As

a

result

of

families to buy house lots there. Land could be sold at higher prices and

this process, Commonwealth Avenue was made more than 50 percent

elegant homes could be built as soon as the land was filled, with wide

wider than originally planned, which was accomplished by narrowing

new streets providing easy access to the rest of the city. In a similar fash-

other streets and reducing the depths of lots. Commonwealth Avenue

ion, the Boston Water Power Company would fill its lands from the ex-

was made 200 feet wide, and there were open spaces of 20 feet in front of

listing shorelines into the Back Bay, starting at the newly fashionable new

the houses on each side. This made a total width of 240 feet between the

South End along Tremont Street.

houses for the central avenue. The increased width of Commonwealth

Strong evidence of social motivations in the planning process is seen

Avenue created the "mall," the middle portion dedicated to trees, shrub-

in the selection of appropriate institutions for the Back Bay, and the

bery, and other ornamental purposes. 53 The roadways on both

sides

reservation of key pieces of land for them (see fig. 3.8). A full block in a

were left the same width as originally planned.

prime area was set aside and donated to the Massachusetts Institute of

The commission set aside about one-third of the Back Bay for public

Technology and the Museum of Natural History.

purposes, with the obvious motive of attracting appropriate residents.

Copley Square, the most important public space after the Common-

Priority was placed on establishing a good system of streets, avenues, and

wealth Avenue Mall, was planned to achieve this significance with the

public squares to make the territory as attractive as possible and to con-

presence of the Museum of Fine Arts and two elite Protestant churches

vince people to select house lots in the Back Bay. 54 Domosh argues that

(Trinity Episcopal and New Old South Congregational). The massive

the plan reflected the control of a small elite and was designed to benefit

Boston Public Library facing Copley Square would be built in the early

only that group SO that Boston could become the cultural capital of the

1890s. Other churches and institutions linked with wealthy Protestant

United States. The design of the area, with Commonwealth Avenue as

society built new facilities in the Back Bay, firmly establishing their place

its local point and rectangular blocks, served the Protestant elite's dual

in "Proper Boston." The commissioners bragged that nearly one-seventh

purposes of setting themselves off from the commercial city that had a

of the land that could have been sold had been donated to the city of

tangle of curved streets, with the Common and Public Garden acting as

Boston and to prominent institutions.

57

an effective barrier, while they remained close enough to the downtown

In 1859, a year after filling began and when the first buildings were

to exercise control. The elite did not flee the central portion of the city of

under construction, a bold plan with a lake was put forward by George

Boston en masse, as the upper class in most cities was doing at the time. 56

Snelling, a prominent Bostonian and a business partner of David Sears.

Dorr Property

#

18

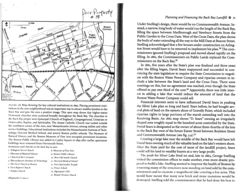

Planning and Financing the Back Bay Landfill 71

0

1/4 Mile

Under Snelling's design, there would be no Commonwealth Avenue. In-

0

1/4 Km.

Boston

Common

stead, a narrow, long body of water would run the length of the Back Bay,

Charles

filling the space between Marlborough and Newbury Streets from the

Beacon

Public

Garden

Public Garden to the Cross Dam. West of the Cross Dam, the plan shows

5

the body of water extending all the way to the Mill Dam at Beacon Street.

Snelling acknowledged that a few houses under construction on Arling-

14

6

15

2

ton Street would have to be removed to implement his plan. 58 The com-

12

4

missioners ignored Snelling's proposal and moved ahead rapidly on the

10

Copley

filling. In 1861, the Commissioners on Public Lands replaced the Com-

Square

11

8

missioners on the Back Bay.59

In 1861, five years after the State's plan was finalized and three years

90

after the filling began, David Sears reappeared and succeeded in con-

vincing the state legislature to require the State Commission to negoti-

ate with the Boston Water Power Company and riparian owners to in-

clude a lake between the State's land and the Cross Dam. There were

Gravelly

Point

meetings on this, but no agreement was reached, even though the State

offered to pay one-third of the cost. 60 Apparently, there was little

inter-

est in adding a lake that would reduce the amount of land that the

Boston Water Power Company could sell.

Financial interests seem to have influenced David Sears in pushing

FIGURE 3.8. Map showing the key cultural institutions in 1895. Placing prominent insti-

tutions in the new neighborhood was an important way to attract wealthy families to the

the Silver Lake plan SO long and hard. Years before, he had bought sev-

Back Bay and give the area a positive image. This 1900 map shows that higher-status

eral plots of land on the eastern shore of Gravelly Point, which included

Protestant churches were scattered broadly throughout the Back Bay. The churches in

riparian rights to large portions of the marsh extending well into the

the Back Bay proper were Episcopal (Church of England), Congregational, Unitarian or

Receiving Basin. An 1862 map shows "D. Sears" owning an irregularly

Universalist, Baptist, and Spiritualist. The closest Catholic Church was tucked outside

shaped area roughly equal to the hundred acres controlled by the State.

the southwest corner of the area, near Massachusetts Avenue, among stables and other

David Sears is designated as the owner of about three-fourths of the lots

service buildings. Educational institutions included the Massachusetts Institute of Tech-

nology, Harvard Medical School, and several Boston public schools. The Museum of

in the Back Bay west of the future Exeter Street between Boylston Street

Natural History and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts occupied prominent locations.

and Commonwealth Avenue (see fig. 3.9). 61

The Boston Public Library was added to Copley Square in 1895 after earlier apartment

Creating a large lake near the middle of the Back Bay would have left

buildings were removed from Dartmouth Street.

David Sears owning much of the valuable land on the lake's western shore.

Institutions and Churches in the Back Bay in 1900:

After the State paid for the cost of most of the landfill project, Sears

1. Arlington Street Church

8. Museum of Fine Arts

, Museum of Natural History

could sell his land to wealthy buyers at a very large profit.

9. Boston Public Library

1. Church of the Covenant

10. New Old South Church

The push for Silver Lake lived on and, late in 1865, George Snelling

Massadisens Institute of Technology

11. Harvard Medical School

visited the commission offices to make another, even more drastic pro-

The First Church in Boston

12. First Spiritualist Temple

posal to build a lake. Snelling wanted to improve the health of Boston by

First Baptist Church

11. Prince School

removing many of the structures now standing on land sold by the com-

Trinity Church

14. Algonquin Club

missioners and to excavate il magnificent lake covering a few acres. This

15. Mount Vernon Church

would have meant that many new brick and stone mansions would be

(Mapworks ID 2005.)

destroyed. Snelling told the commissioners that he had done his best to

72

o

Boston's Back Bay

Planning and Financing the Back Bay Landfill

73

Among other issues, the resolve called for making some funds available

Mill

Dam

before any land was sold by allowing the governor to draw up to ten thou-

sand dollars from the state treasury to be used by the commissioners for

the

initial

filling. 64 A short time later, the resolve was revised, with the

Commonwealth

only change being that the governor's power to draw the cash had been

removed. Therefore, the State Legislature stipulated that, until land sales

began, no money at all would be taken from the treasury for the project

Boyiston St.

except to cover incidental expenses of the commission. The commission-

ers would have to find ways to fill the former tidal marsh economically

Gravely Point

David Sears

with innovative approaches to financing so the project would not bur-

den the taxpayers.

From the beginning, the commissioners faced a dilemma when the

Crafts

Hathaway

State Legislature refused to provide any start-up money for commenc-

ing the landfill process. The contractors' bids in 1857 had called for start-

up payments so they could assemble their equipment and workers; with-

out this, the cost per cubic yard for filling the area would have been

D. Sears

much higher. The commissioners' solution in 1857 was to sell a large

piece of unfilled land on Beacon Street about a year before the contrac-