From collection Creating Acadia National Park: The George B. Dorr Research Archive of Ronald H. Epp

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Search

results in pages

Metadata

[Series III] Cambridge

/

Caubnidge

Cambridge Historical Society Perceadings.

v.30, (1945) Pp. 11-27.

Ant

with

11/07/

PAPERS READ DURING THE YEAR 1944

HARVARD SQUARE IN THE 'SEVENTIES

AND 'EIGHTIES

By Lois LILLEY HOWE

Read January 25, 1944

T

HESE Reminiscences, which should really have been called Har-

vard Square and its Environs in the 'Seventies and 'Eighties, have

been in the back of my mind long enough for me to have verified details

Dee

X

by talks with Miss Elizabeth Harris and Mrs. Archibald M. Howe, both

1873

of whom have been gone for years.

I have also to thank my old friends Charles F. Batchelder, Frances

foundations

Weld Carret and George L. Winlock for reading and commenting on

my statements - and Walter B. Briggs, always helpful and interested,

who almost the last time that I saw him suggested my going to Mr. Ed-

anniversalism

ward L. Gookin at the Widener Library, who has shown me many

p.r

photographs of the Square as I remember it.

At the second meeting of this Society, being its First Annual Meet-

ing, October 30, 1905, Mr. Charles Eliot Norton gave his Reminiscences

of Old Cambridge. These went back nearly as many years in his lifetime

Halyoth House p.23

as mine do now.

He said that in his youth Harvard Square was known as the Market

Place. I remember that we were amused because the Misses Palfrey

spoke of it as "The Village." I have seen it change from the focal point

of a small town to what it is now, a suburban centre, distinguished from

others of its kind only by the fact that the buildings of Harvard Univer-

sity form part of its boundaries and SO add to its prestige.

But in the late 'seventies and early 'eighties of the last century, Old

I 2

THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Cambridge was still a small College town and had an atmosphere of its

own. As a child, I was allowed to go to school or anywhere else without

any escort other than a contemporary one. I was sent to the Square on

errands; I even disported in the College Yard, which lay between Harvard

Square and "our house" on the corner of Oxford and Kirkland Streets,

now known as the Peabody House.

There were, of course, two ways of going to Harvard Square from

this corner, either across the College Yard or around the outside. If you

were less than say fifteen, you naturally went across - who would dream

of going all the way round?

"Alas! Regardless of their doom

The little victims play,

No thought have they of ills to come

Nor care beyond to-day."

I supposed vaguely that "some day" I should be "grown up," a desir-

able state when the round comb would disappear, the braided pigtail be

"done up" on top of my head, and my dress would be long and flowing.

Then of course I should be able to do anything; that I should then be told

"You must never go through the College Yard" never occurred to me. It

was a great blow when it came.

I don't think I shall ever forget my amused surprise when I went

through the Yard one summer two or three years ago when the girls of

the summer school occupied the dormitories and I saw them lying about

on the grass - not in Victorian costumes, either.

So across the "Yard" I always went. First across the Delta, and

diagonally over to the gateway between Thayer and Holworthy. There

is a handsome wrought-iron gate there now, with brick posts and "1879"

on the lantern above it, but at the time I am thinking of the members of

the Class of 1879, who were eventually to present that gate to the College,

were either undergraduates or just adjusting themselves to life in a new,

and perhaps bleak, world. The College fence was like that still around

the Common, rough granite posts, with squared wooden rails between,

except that the Common fence has but two rails and the College fence

had three. The Delta had originally had the same kind of fence, but

around the Gymnasium, a building dimly reminiscent of an early Byzan-

tine Church, standing where the Fire Station now stands, the fence was

HOWE: HARVARD SQUARE IN THE 'SEVENTIES

13

diversified by having iron chains instead of wooden rails between the

posts. They hung rather loosely but not loosely enough to be comfortable

to swing on.

Once inside the Yard there was a real choice of route to make, whether

to go left along by Thayer Hall, turning diagonally in front of Univer-

sity, or at once to turn right toward the College Pump, where was pre-

sented another choice, whether to go across to Church Street, or again

diagonally between Massachusetts and Matthews; and almost everybody

but me seems to have forgotten that there was another pump between

those two buildings. Pumps have possibilities as sources of entertainment.

All the walks were paved with flagstones and of course it was very im-

portant not to step on any of the cracks.

In those pre-telephone days the butchers and the grocers kept sepa-

rate shops. Both came around in their carts every morning and took

orders for food which they delivered later. Some butchers to be sure

came to the door with the meat in their carts and the customer could go

out and look at it and buy it right at her own door. There was a man,

named Raymond, with whom my aunt dealt, who did his business this

way. He drove a white-canvas-covered cart and wore a white frock. He

lived in Chauncy Street, which has come up in the world since then, at

number 23. I think he built that house SO long occupied by Mr. and Mrs.

George H. Browne, and the little apartment house next door was made by

the Brownes out of Raymond's stable. He was a real character and on

one occasion, when my aunt had expressed herself with some acerbity

about a verv tough leg of mutton which he had sold her, he said softly,

"Why Mis's Devens, you do surprise me; Mis's Storer, she had the mate-

leg and she thought it was real good."

My father ordered the meat himself and he dealt with Mr. Farmer,

on the corner of Church Street. Farmer had succeeded to the business of

a man named Wallace, of whom it was said that his last dying words were,

"Don't forget Dr. Howe's Sunday roast o' beef."

Opposite Church Street was then, as now, the main entrance to the

College Yard, the Gate of Honor, through which the Governor of

Massachusetts, escorted by the Lancers, drove on Commencement Day.

It was about one carriage wide with dressed granite posts and an iron

gate. On each side was a footpath gateway with three turned iron posts

in it. All the foot gates had posts in them; some were wooden posts with

14

THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

close-fitting iron caps. The church was of course opposite, but Charles

Sumner did not sit presiding over the open space between. He was, I

think, sitting on the Public Garden in Boston. His present location is an

appropriate one for he roomed in Hollis and Stoughton while in College

and boarded with my Grandmother at Number Two Garden Street, now

Dr. Norris's house.

There was a section of the Common, bounded by Garden Street,

North Avenue, Holmes Place, and what was afterward named Peabody

Street. Through this ran Kirkland Street to Garden Street. It was un-

doubtedly a relic of the days when the Common was not fenced in, and

was part of the road to Watertown. It was the direct road from our

house to Two Garden Street. It was not of much interest to the City and

my elder brother and sister, who frequently went to sec my grandmother,

named it "The Slough of Despond." (They were interested in Pilgrim's

Progress.)

Of the two little Commons thus formed, one was for obvious reasons

called "The Flag Staff Common" and the other was to us "The Mad Bull

Common." I think a sick cow had been pastured there once and she prob-

ably bemoaned her fate. Now the Subway has taken up most of the

space, but the old fence is still left.

Church Street was primarily connected in my mind with going to

Sunday School in the ugly old Parish House, or, as we called it, the

Vestry, of the Unitarian Church, where Miss Edith Longfellow was my

teacher until she married Richard Henry Dana 3rd. But there was more

or less of interest in the street itself, in which there were a variety of

features. There was no high and forbidding brick wall on the north side

but an open space extending all along back of College House. It be-

longed to the College and had a fence like the College fence, with an

opening through which carts could pass to the back doors of the stores.

There was also an unpretentious house which had been built for Jones,

the College Janitor, a well-known character.

There was a fire in Hollis Hall, in the top story, some time in the

early part of 1876. I remember it very well for it was obliging enough to

break out in a spectacular manner just as we were having recess at Miss

Page's School on Everett Street. We could see it very clearly all across

Jarvis Field and Holmes Field and we went in a body. So did all the

students and all the faculty of Harvard College. In the middle of the

HOWE: HARVARD SQUARE IN THE 'SEVENTIES

15

excitement came twelve o'clock and the sound of the College bell ringing

for a recitation which no one was likely to attend. Mr. George Martin

Lane was heard to say, "There is Casabianca Jones doing his duty as

usual." Many years afterward, Dr. George P. Cogswell had his first

office in this Church Street house.

The other end of the Street really belonged with Brattle Street. On

the southwest corner was the Bates house, with its gates, its arbor and its

garden, to my mind one of the beauty spots of Cambridge. The house

was moved to Hawthorn Street when Church Street was widened in

1929. Samuel Chamberlain has photographed it there. I wish he could

have seen it in its original setting. Its north wall was on the street line and

was continued by a white board fence which enclosed the garden. There

were two or three other pleasant-looking houses on that side of Church

Street. At the northwest corner the Francis Dana House also belonged to

Brattle Street, but there still stands high up on Church Street what I used

to hear called "Dr. Wyman's old house," though Dr. Wyman had not

lived in it for many years. It has been saved for us by various organiza-

tions and is now occupied by the Red Cross. Miss Jaques took boarders

there. Miss Harris told me that she had been trained as a tailoress and that

her mother used to wear a white turban. Miss Julia Watson lived with

her. In the Unitarian Church we thought nobody could arrange flowers

as well as Miss Watson. Mrs. Stephen G: Bulfinch, the daughter-in-law

of Charles Bulfinch, the celebrated architect, lived here with her daughter,

Ellen Susan, who was a friend of my Sister Sally's and a member of her

"Club," the first of the Sewing Clubs. When I was about fifteen, I took

lessons in "sketching" from Miss Bulfinch in the pleasant southwest room

on the second floor. I remember a wide upper hall with a figured oilcloth

on it.

The greater part of the north side of the street was taken up by Pike's

Stable (afterward Blake's). It would be difficult to imagine now how im-

portant this was to Old Cambridge. From it came numbers of "hacks,"

each with two horses, to take the quality to dances, lectures and concerts,

to weddings and funerals, day and evening. In the snowy winter days

the bodies of the hacks were put on runners to form so-called "boohy-

huts." There was a great deal of "seat work" practised; that is, every one

paid for his or her own seat, generally twenty-five cents. The driver

picked up a load, going or coming. It might be strange to an outsider to

16

THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

hear a maid announce "Carriage for Miss Jones and Mr. Eustis" but we

were used to it, and you may be sure that Miss Jones had some other

"girl" to accompany her on the perilous ride home, for no young lady

was ever allowed to go anywhere in a carriage alone with a gentleman.

Muirhead in his book on America, as late as 1893, speaks of the peculiarity

of the Boston custom (and that of Cambridge was the same), which did

not allow a young girl to go anywhere alone in a carriage with a young

man she knew, but allowed her to be chaperoned by any cab driver.

In the middle of the north side of the street you may still see a smug

little brick building, now occupied by A. Lavash, the carpenter, and the

Cambridge School of Art. This had been the Police Station, and next to it

was what had been the fire engine station before both had been moved to

the then new City Building in Brattle Square. The engine house had a

little belfry at the back overlooking the Burying Ground. I suppose this

was where the original fire bell was hung. The site is now occupied by the

Cambridge Motor Mart and the sill of one window is of weathered

granite, on which is deeply cut "CAMBRIDGE 1," a relic of that fire

engine station whose materials had been used for the Motor Mart.

But the most fascinating thing on Church Street I cannot exactly lo-

cate. That was a blacksmith's shop. Mr. Gookin thinks it was on Palmer

Street. Miss Carret thinks there was one on Palmer Street and one on

Church Street too, and both she and George Winlock remember a wheel-

wright's shop which I do not remember. The latter says that A. J. Jones

had a "Carriage Repository" on the corner of Palmer Street, "a narrow,

plain building, three stories high, with three large doors and a projecting

beam at the top to hoist the wagons and carriages." Wherever the black-

smith's shop may have been, I surely did like "to look in at the open door

And loved to see the flaming forge and hear the bellows roar."

Errands for my family usually sent me elsewhere. The path between

Massachusetts and Matthews came out of the Yard through a gate with

five iron posts in it, just about opposite the centre of College House or

University Row, which then, as now, had shops all along its lower story.

This gate was approximately where the present gate of the Class of 1875

stands, between Straus and Lehman Halls. Danc Hall, then the Harvard

Law School, afterward the first home of the Harvard Co-operative Soci-

ety, stood just to the south of it.

I cannot remember all the shops that were there but Farmer, the

HOWE: HARVARD SQUARE IN THE 'SEVENTIES

17

butcher, as I have said, had that on the corner of Church Street. The

Post Office, which had a peripatetic habit until it had the present building

all of its own, was at one time here. Near where the street bends, the

little triangular shop, now occupied by a florist, was that of one of the

most interesting characters in the town, James Huntington. "Old Hunt-

ington," as we used to call him, was a watch and clock maker of great skill

and a very eccentric individual. Thanks to Mr. Edwin H. Hall, who

gave this Society an account of him in 1925, I can tell you that he was a

descendant of a signer of the Declaration of Independence. He worked

his way through Harvard College, graduating at 30 in the Class of 1852,

and trained other workmen and had enough business to maintain another

workroom, but always himself worked in the little shop. He disliked

publicity and never advertised or had a sign on his shop. He always

signed his bills just "J.H."

A friend of ours, who had a watch she wanted to sell, brought it to him.

He offered her something like eighteen dollars, a very disappointing re-

sponse. Said she, "A man in Washington told me it was worth thirty

dollars." "Did he say he would give you thirty dollars?" was his charac-

teristic reply. He founded a home for orphan children which would

have naturally been called The Huntington Home. This he forbade and

it was called after the street on which he lived, and SO we know it as The

Avon Home.

In the middle of the row was one of the - to me - most important

shops in the Square. Perhaps I was sent there more often for a yeast cake,

a thing very frequently forgotten. This was a grocery store, usually

spoken of as "Wood'n Halls," properly Wood and Hall's. I think there

were two doors, that it was two shops wide, but only one was in common

use. The doors were two-fold and on the door posts were signs in

bold black letters on white grounds advertising their specialties, among

which I only remember W. I. Goods - I suppose rum and molasses from

the West Indian Islands. Inside, I remember the shop as dark and rather

mysterious. I remember dim gas lights made necessary on rainy or winter

days by a broad wooden awning which covered the sidewalk and made it

handy to unload or load barrels and perishable wares in bad weather. I

think also some of the carts were loaded or unloaded in the rear in that

open space that came from Church Street. I certainly have a vision of a

wide door there, open in the summer. On the right of the entrance, inside,

18

THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

was a long counter where retail business was conducted; on the left, a

mysterious collection of boxes and barrels and the scales on which we

children used surreptitiously to weigh ourselves, though probably no one

would have minded if he had noticed us. It gave us a feeling of being

rather smart and tough, and you must remember that there were no bath-

room scales then and it was important to know how our weights as well as

our ages compared.

Mr. James Wood and Mr. Orrin Hall, two of our finest fellow citizens,

presided in person over the business they had built up. They also had an

assistant named Norris. They did not wear white linen office coats but

long brown linen dusters, and I always think of Mr. Wood as having a

black beard and a square derby hat while Mr. Hall, who was a remarkably

handsome man, figures in my memory as clean shaven with a Panama hat.

At the end of the Row were the two banks, the Charles River Bank

and the Cambridge Savings Bank, side by side, and looking to me just

alike, with green leather doors. After them came Lyceum Hall, where

the Co-operative Society is now. There was an open space or passage

between that and the banks. Lyceum Hall, without being pretentious,

had some claim to architectural style. It had a classic portico at the head

of a wide and imposing flight of steps. Behind this flight of steps there

was, in the basement, an oyster bar of no interest to me. I think a tailor

shop occupied the first story. The Hall was on the second and was ap-

proached by a flight of stairs as nearly continuous as possible with the

outside flight. Up these stairs, on dancing-school days went my little feet

in their rubber boots, around to the right at the top, into and across the

whole length of the hall to the dressing room at the far end and all to the

tune of Mr. Papanti's fiddle as he coached some special pupil. This was

not the original, distinguished "Papanti" but his son, never as good a

teacher and really living on his father's prestige. Still there it was we all

learned to dance. Will there ever be a greater thrill than leading the

Marching Cotillion at the Dancing School Ball?

Brattle Street begins here, though it always seems a part of Harvard

Square to me. The first little fruit stand was tucked into a crack next to

Lyceum Hall. Here one Baccilupi sold peanuts and bananas. Then came

another triangular store where Ramsay dispensed drugs. This was the

shop to which James Russell Lowell alluded in the many times told pun

when he said he would rather see Ramsay's in Harvard Square than

Rameses the Great in Egypt.

UNIVERSITY PRESS

HUMPHREY HOUSE

Corner Brattle Street and Brattle Square

Mount Auburn Street and Brattle Square,

On extreme right, the Brattle House

facing across Brattle Street

HOWE: HARVARD SQUARE IN THE 'SEVENTIES

19

Further on was the fish store of Alexander Millan, with that marvel-

lous aquarium in the window. I wonder whether it is the same aquarium

or its great-grandchild which graces Campbell and Sullivan's shop on

Church now. Do children flatten their noses against the window to see

it? I suppose aquaria are now SO common in the home that it does not

prove as alluring as that did to mc, although to be sure there was beneath

the window one of those dreadful grilles over an area, which were SO

alarming - you really knew you could not possibly fall through, but you

might catch your toc!

David Brewer kept a butcher shop on the further corner of Palmer

Street. His brother Tom, a somewhat noted and notorious character,

ran a similar business across Brattle Square. Around on Brattle Street the

Worcester Brothers had a furniture store in a new brick block, in which,

upstairs on the second floor, was the office of Dr. Andrews, the dentist.

My aunt Mrs. Devens once went to Worcester Brothers to give an order,

for they were famous people for repairing upholstery and taking up and

putting down carpets (this last piece of business being quite unknown in

the present day). She said in her forceful way: "I should like to have all

the brothers come before me and take this order, SO that no one of you

can say, 'You must have given that order to my brother, I never heard

anything about it'."

Between this building and the Bates House on the corner of Church

Street were three houses, variously occupied. That next to the Bates

House was three stories high, tall and narrow with its end to the street,

of the same type as Christ Church Rectory. In this, upstairs was a very

good dressmaker, who must have had great courage to adopt that business,

as she bore the unfortunate, for her, name of Miss Fitz.

These formed the northwest side of Brattle Square, which had at that

time a certain distinction of its own. As you look from Harvard to

Brattle Square today, the vista is closed by the Post Office and the Re-

serve Bank, but then you would have seen the University Press. This

was a very large building and as it was always painted a dirty brown, I

think we all thought that it was a shabby old hulk. As a matter of fact it

was quite a fine piece of architecture, originally built for a hotel, the

Brattle House. It was occupied as a dormitory by students for several

years prior to 1865, about which time it was taken over by the University

Press. Its proportions were good and SO was its detail. It was three stories

high above a brick basement. The stories were of graduated heights, as

20

THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

was shown by the windows. The walls were divided into panels by

pilasters. There was a mansard roof with dormers and it was crowned by

a cupola. There was a porch on the Brattle Street side and a portico with

Ionic columns on the end toward Brattle Square. There was no more

imposing building in the Square. Certainly not its neighbor across Mount

Auburn Street, the City Building, bearing all the architectural faults of

its period, the Seventies, with a much beturreted mansard roof and an

illuminated clock. This was the home of the Police Station, the Fire De-

partment, and the Police Court. The site is now part of the Boston

Elevated Railway's train yard. In the top of this building was Armory

Hall, destined to outshine Lyceum Hall as a ballroom and eventually to

be cut out for that purpose by Brattle Hall. Here it was that later I and

many of my contemporaries "came out" in society.

My first memory of this hall is of an affair there which may have had

to do with its own opening to society or perhaps with some one of the

spate of Revolutionary Centennial anniversaries which swept this part of

Massachusetts in the early Seventies, beginning with that of the Boston

Tea Party, in December 1873. At any rate there I was with my whole

family (an unusual circumstance in itself) having supper and demanding

chicken salad. I can't think why, nor can I understand why it was refused,

but I was much injured by the refusal. Wandering around to amuse

myself, I met a schoolmate, Winifred Howells, about to have supper with

her father William Dean Howells, distinguished author and fellow towns-

man. Of course I poured out my woes to them. And wasn't it wonder-

ful? I had supper again with them and to my surprise I had a plate of

chicken salad served to me.

There was on Mount Auburn Street some distance to the west of the

City Building, on the corner of Nutting Place, a very pretty old house,

similar to the Bates house. It had two very good gates and was set up on a

retaining wall. As it was painted an ugly brown it did not receive as much

notice as it might have, and no one thought of buying it and moving it

away, as was done with the Bates house. On the other corner of Nutting

Place was a fine large French roofed house of a type much used on North

Avenue (that part of Massachusetts Avenue leading from Harvard

Square to Arlington). This was very handsome in its way and was on

a terrace with a granite retaining wall and had a driveway to the front

door; there must have been a stable somewhere but I do not remember it.

HOWE: HARVARD SQUARE IN THE 'SEVENTIES

2 I

The Cambridge Garage now stands there. A little above this, on the other

side of the street, are still two dignified Victorian houses peering sadly

around past the cheap apartment houses that have been built in their front

yards. All of which shows that Mount Auburn Street once had high

hopes and makes us thankful that we were able to keep the electric cars

off Brattle Street. It was a tough fight to do so.

At the southeast corner of Brattle Square was a dignified Greek Re-

vival type of house with big fluted pillars across the front. It stood up

high, about where the white brick filling-station now is and certainly

gave an air to the locality. This was the Humphrey House, in which lived

Mr. Francis Josiah Humphrey, Secretary of my father's class, Harvard

1832. My father sat between him and John Holmes at all lectures for the

four years of College. The Commencement Punch of that class was

always at our house and Mr. Humphrey always demanded a kiss from

"the baby" before he left.

On the way back to Harvard was the Holly Tree Inn on the east side

of Brattle Street. Of this I have no recollection, but Miss Frances Weld

Carret writes of it as "that picturesque story and a half house with the

porch all across the front and the yard all around it. The whole Square on

that side was SO open with fewer buildings." Miss Carret lived in Appian

Way and probably always approached the Square through Brattle Street,

while I came from the other direction. I have also been told that the best.

beer could be procured at the Holly Tree Inn, but that did not interest

me at all. I think however that it was the first public eating place in that

neighborhood. The students were supposed to eat at Memorial Hall.

At the point between Brattle and Boylston Streets was the hardware

store of I. P. Estes, in a wooden building up quite a number of steps.

I

have been told that his name was Ivory Pearl. His wife was a nurse and I

can testify that she was a good one. In those days there were no trained

hospital nurses.

The name of Boylston Street was originally Brighton Street, obvi-

ously because it led to Brighton. It was changed because Brighton was

not very stylish and moreover it was associated with what we now call

the "Abattoir," then the Slaughter House. When the Abattoir was built,

the fire alarm was rung from it and we always called it "the Brighton

Bull." I suppose it was to this bourn that large droves of cattle were led,

which came through Harvard Square from North Avenue from time to

22

THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

time at no stated intervals. They were more or less alarming; we some-

times spoke of them as Texan Rangers, but I never heard of their doing

any harm. They probably came from the West via Porter's Station, but,

though usually of an inquiring turn of mind, I never asked about them

nor connected them with "Dr. Howe's Sunday roast o' beef."

On the south side of the Square, between Boylston and Dunster

Streets, were the oldest buildings: three frame houses, with shops built

into their lower stories. The two-story house on the corner had an unusu-

ally wide gable with an arched window in the middle and a window on

each side, all still having blinds. The next, on the other side of what had

been a lane across which the shops had been built, was a former farm-

house, end on to the Square and built close against an old tavern. I can-

not remember the exact sequence of the shops except the first and last.

The first was the grocery store of James H. Wyeth, a friendly rival to

Wood and Hall. It had been recently moved here from Brattle Street,

near Ramsay's. Mr. Wycth was a familiar figure in the town, another

good fellow citizen. He retired many years later to grow oranges in

Florida. In the second story of that building a young Swede had recently

established a shop for framing pictures. His name was J. F. Olsson and

his family carry on the business today.

I should say that Richardson's bookstore was next to Wyeth's. This

became that of Amee Brothers later. Here it was that Lee L. Powers

was He

introduced to Cambridge commercial circles, where he eventually

made a reputation as an unusual, if not lovable, character. graduated

from the sale of books to that of antiques in general and furniture in par-

ticular. Then there was Mann's (afterwards Moriarty's) Boot and Shoe

Store, where my earliest shoes, "ankle-ties," and rubber-boots were

bought. All those shops were low-studded and this may have been built

into the passage - because I remember a back shop with a ceiling light

over it. The Mann Brothers were as like as twins, undersized and always

seeming to me like gnomes in a cave. The days of "packaging" had not

arrived and when any kind of footwear was desired, the salesman groped

in a large deep drawer, containing quantities of shoes of the type desired.

When he had got hold of one shoe, he pulled it out. The mate came with

it because they were fastened together by a string which ran from shoe

to shoe through the stiff part just above the heel. A knot at each end of

the string kept the shoes from being disconnected.

HOWE: HARVARD SQUARE IN THE 'SEVENTIES

23

Mr. Charles Eliot Norton is my authority for the statement that the

last of these compartments, the waiting room of the Street Railroad, was

in a part of what had been Willard's Tavern. It was an unattractive, dingy,

low-studded room; very dark, although its whole front was of glass. In

winter it was heated by an airtight stove. Next to this building, where

the Cambridge Savings Bank is now, was a three-story brick building on

the ground floor of which was a confectioner's shop. This was originally

kept by a man named Belcher, a cheerful bearded man with a smiling and

bossy wife, but they disappeared from the picture very early, when they

sold out to their saleswoman, Miss Martha R. Jones, who became one of

the most noted people in the Square. We delighted in her sign on the

window, M. R. Jones, and to call her Mr. Jones was scarcely a misnomer.

In an age when sport clothes were unknown even to men, and all women

were dressed in supremely feminine garb, Marthy Jones's costume was

distinctly mannish. She probably would have rejoiced in "slacks," but at

that time it was against the law for women to wear trousers, SO she wore

a very masculinc-looking coat over her long plain dress. Her hat also was

more or less like a man's, of a shocking bad type, and I can not remember

her in any other dress. But she sold good candy to the muffled rumble of

a printing press on the floor above, on the site of Stephen Daye's press,

the first in the Colonv. We must have bought our icecream from her too.

Down Dunster Street, past the car barns and on the other side of

Mount Auburn Street, was Wright's Bakery. Mr. Wright's son, George

Wright, was another of our leading citizens and a member and benefactor

of this Society. Here it was that we bought brown bread for Saturday

night or Sunday morning, and we could have bought baked beans too.

And we did buy Brighton biscuits, large scalloped cookies with shiny

granulated sugar all over them.

Across Dunster Street from Martha Jones's were two modern build-

ings, Little's Block and Holyoke House.) These had students' rooms up-

stairs, I suppose the first expansion of the College from the dormitories in

the Yard; forerunners of Beck Hall and the Gold Coast. On the ground

floor were the most modern shops. There was F. E. Saunders' Drygoods

Store on the corner. Here were obtainable all sorts of what are known

as "small wares" and many other things. It was said that Edith Long-

fellow bought her wedding dress here, when she married Richard Henry

Dana, Third. That was the first place where I remember buying any-

24

THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

thing. What it was I do not remember, only that my watchful aunt Miss

Mary Howe was supervising the purchase and she reproved me for hand-

ing my money to the saleswoman before I received the equivalent. And I

remember the money too. It was a twenty-five cents bill, a greenback,

like a small dollar bill. I never saw a silver quarter of a dollar until I was

as much as twelve years old, when the United States resumed specie pay-

ments after the Civil War. We then just said THE WAR.

Mr. Saunders was famous for his Ollendorffian remarks, somewhat

like a foreign phrase book. When you asked him for something he did

not have he suggested something else which was not usually in the same

class. It was possibly his way of stimulating trade. That was the first

store where I ever saw a sale of Christmas goods, and more than that,

they were Japanese. Probably the first unloading of the products of Japa-

nese cheap labor! Many of them were very pretty and wonderful for a

child to buy. I think I still have a Japanese lacquered glove box which

must have come from there.

John H. Hubbard kept the apothecary shop next door. The same

shop you know as Billings and Stover's Drug Store. Many years after his

retirement, I met him and he showed me a tintype of himself standing be-

side a big high-wheeled bicycle. He told me with pride that it showed

he was a pioneer in two things, amateur photography and bicycling. He

had of course developed and printed the tintype himself. I have been

told that he played the trombone in the Pierian Sodality orchestra for

many years. My acquaintance with a soda fountain began in this shop,

but that was some years later. There was no icecream in the soda, only

a sweet syrup. We preferred to go for that to Mr. Bartlett's store, which

was, I think, where the Cambridge Trust Company is now. Probably

this was on account of the personality of Mr. Bartlett, who served us

himself and liked to talk to us.

The University Book Store was distinguished and stylish. It did not

look like a country store as many of the others did. Of course I was

proud to go there, because Mr. Sever, who kept it, was the father of my

very intimate friend and much of my playtime was spent at his house. He

was a handsome man, rather grave and severe, and I held him in awe,

though he was always very kind to me.

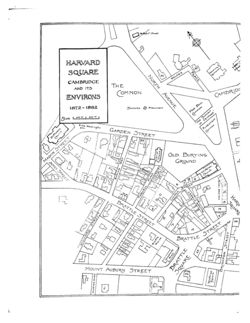

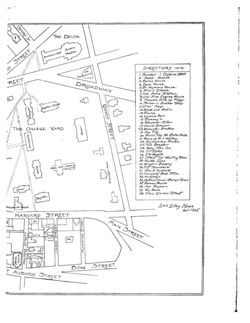

Probably no one ever thought of Harvard Square as "pretty," yet if

we could see it today as it was fifty or sixty years ago, we should say that

Church

HARVARD

35

SQUARE

36

CAMBRIDGE

THE

AND ITS

COMMON

ENVIRONS

1872 ~ 1882

JOLDIER'S FY MONUMENT

Scale

1004 & 200 H

Holder.)

The Elm Washington

chapel

GARDEN STREET

38

[

OLD BURYING

GROUND

ml

Arb

16

MOUNT AUBURN STREET

(ilv

guilding

THE DELTA

Sundars

Street

Hall

Theatre

I

DIRECTORY 'co'

Old

GY'

nasium

/ Number / Oxford street

2 "Jones" House

REET

3. Bates House

BROADWAY

4. Dana House

5.0r Wyman's House.

6 Pike's Stable.

7.Old Police Station.

8.Old Fire Engine House

a

9. Probable SiTe of Forge.

10 Farmer's Butcher Shop

11.WJ Shop.

12 Wood and Hall's.

13 Banks-

14 Lyceum Hall.

15 Ramsay's

16 Alexander Millan.

JESSE

17 David Brewer

THE COLLEGE YARD

.18.Worcester Brothers

19. Miss Fite

20 House like the Bates House

21 House of W.L.Whitney.

22. House.

Humphrey

23.Tom Brewer

-

24. Holly Tree Inn.

25. I.P.Estes.

26. J.H.Wyeth.

'ump

27 Street Car Waiting Room

28. Martha Jones.

29. Wright's Bakery

Gore Holl Libra'

30.F.E. Saunders

31 John H.Hubbaid

32 University Book Store

33. Mc Elrey's

34 Apthorp House Bishop's Palace

35 Holmes House

36. Mrs Baker's

Grays

37. Foy House

38. TWO Garden Street

Boylston

Wadsmonth House

Lois Lilley Howe

del-1945

HARVARD STREET

32

33

MAIN

STREET

34

Bow

STREET

T AUBURN STREET

HOWE: HARVARD SQUARE IN THE 'SEVENTIES

25

it had a certain charm. While many of the buildings were not beautiful,

none were hideously commonplace. The low country-like fence around

the College Yard and the lawns between that and the College buildings

made the Yard all of a piece with the Square and gave a quality and

atmosphere which has now entirely gone. Wadsworth House, instead

of being huddled in between other buildings, looking as if it had made its

last stand at the edge of the sidewalk, had a yard in front of it with a

lilac hedge between that and a handsome Colonial picket fence, all of a

piece with its old New England charm. There was also a row of trees

along that side of the street. (This was Main Street then.) All this

vanished when the street was widened, some time in the nincties, I think,

on account of the electric cars. Might we call this the first step in

"mechanization"? There were trees in front of Lyceum Hall and College

House too. I do not remember the big elm with a low stone wall around

it, near which stood a watering trough and the hay scales. As far as I can

make out from photographs, these stood just about where the subway

station now stands. They were removed in the early seventies because

they obstructed traffic!

The Square, then, as I remember, had some of the charm of an open

space and was not too crowded. But there was one important feature

which we never thought even picturesque until it was gone forever -

the horse.

Horses were everywhere; on the tradesmen's carts, on the ice carts,

the express wagons, as well as on the private carriages of our more wealthy

citizens. Likewise there were the horsecars. Funny little things we should

think them now, used as WC are to huge electric cars and busses, not to

mention stream-lined automobiles and enormous trucks. They were

low and square and yellow with flat roofs. Each was drawn by two stal-

wart horses (four when snow was on the ground). These were brought

up from the car-barn on Dunster Street all harnessed, with pole and

whiffle-tree to hook on to the car whose horses were to be changed.

Stout-bearded Irishmen brought them. I remember one jolly "Brian"

with a Falstaffian figure, a brown beard and a twinkling eye. He used to

bring pails of water for the horses from the watering trough and pump

for this purpose in front of Dane Hall.

There was not SO much changing of cars in the Square. You took the

car you wanted in Boston and came out through Main Street, now

26

THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Massachusetts Avenue. Some cars went up Brattle Street, some up

Garden Street, some up North Avenue, now Massachusetts Avenue.

People who lived on Kirkland Street did not have to come to the Square

to go to Boston. They could take a Broadway or an East Cambridge car.

Each car had a driver and a conductor. You did not pay as you entered;

the conductor came through the car to get your fare, no matter how

crowded it was.

These officers did not wear uniforms, unless the huge buffalo-skin

coats and caps the drivers wore in the winter might be SO considered.

For these the modern expression "battle dress" would seem to have been

appropriate when we think of their driving across the West Boston Bridge,

one and a quarter miles long, in stormy winter weather. I think, if you

look up the facts, which I give from memory, you will find that even

after electric cars came in, the vestibules were not enclosed for several

years. There was great discussion about it. Many people thought the

motor men would not be able to see as well and were sure reflections on the

glass would be confusing and dangerous. Hence the curtains which they

sometimes drew across.

The passengers inside the cars, though shielded from the fury of the

elements, were also cold. The Company did its best by filling up the

floors of the cars with straw, which helped indifferently well to shield

the passengers' feet from drafts from the floors. It was changed quite

often but could not be kept very clean when snow melted into it and mud

joined the snow. - But what pleasant, neighborly visits we had on those

long cold rides, as well as in the summers when the open cars were used.

There were hay scales in front of Dane Hall, then the Harvard Law

School, and also a stand, not of cabs, but of express and "job" wagons.

Sawin's Express was the only express, but I remember that Henry Lewis,

a tall colored man, who tended our furnace, had a cart there. According

to the fashion of the time, it was very high with a high scat across the

front, and was for "furniture moving" purposes. Moving, in those days,

was not done with discreet closed and padded vans, but in such a wagon

as I have described. Some care was exercised to protect the handsomer

pieces of furniture, which were put at the bottom of the load and covered

with fairly clean cloths. The shabby pieces were on the top, inadequately

draped with bits of burlap. This arrangement made a load of furniture,

HOWE: HARVARD SQUARE IN THE 'SEVENTIES

27

even of one of our most wealthy citizens, look a good deal like a Morgan

Memorial wagon on a day when it has made a good haul.

But to return to the shops. There was not really much of interest

beyond Holyoke Street. There was to be sure the "Bishop's Palace"

(the Apthorp House, now Adams House, the Master's residence). Al-

ways mysterious to me, it stared across a dead garden where are now

shops, instead of a picket fence along the Street. There was another little

delta between the foot of Quincy Street and Main Street, with a fence

around it. But near the further corner of Holyoke Street was one most

important shop. Over it was the sign "Confectionary," and within, the

proprietor, who looked like the knave in a pack of cards, only he did not

wear a hat, sold candy and toys. I have been told that he served icecream

in his back shop and that as the floor was cold because there was no cellar,

he had straw laid under the woolen carpet.

In the front shop was the candy, sometimes chocolate mice with

brown string tails, and more important, paper dolls, with famous or dis-

tinguished names. I only remember Clara Louise Kellogg. Was she an

opera singer? How illusory is fame! She came printed in colors all ready

to cut out and with dresses, too. And there were china dolls of several

sizes and prices suited to the infant purse, but all alike, perfectly stiff

with only the arms sticking out as if to join in a boxing bout. Sex was

determined by the hair - worn in bunches over the ears and a pointed

pompadour by the boys, and in curls around the head by the girls. Very

valuable and precious these were, and easy to dress with very little ma-

terial, except that the legs being almost tight together, it was hard to

manage trousers for the boys. The dolls were very easily broken and SO

had to be replaced when one's budget permitted.

And from this shop I usually skipped happily home along the path

between Gray's and Boylston Halls and past University, taking care, of

course, not to step on any crack in the flag-stone walk, though some of the

stones on that path were very wide and it was extremely hard to manage

those with one step each.

The Romance Of Street Names In Cambridge The Cambridge Historical Society

Page 1 of 5

HIS

S

TheCAMBRIDGEHISTORICALSOCIETY

HOME

EVENTS

ONLINE RESOURCES

PUBLICATIONS

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVE

HOOPER-LEE-NICHOLS H

The Romance Of Street Names In Cambridge

Se

Submitted by Ken2 on Tue. 12/03/2013 - 2:26pm

Searc

Author: Frances H. Elliot

(sid)

Volume: 32

An

Pages: 25-29

Year (

Years: 1946

prese

Copyright: 1949

Publishers: Cambridge Historical Society

THE ROMANCE OF STREET NAMES IN CAMBRIDGE

BY FRANCES H. ELIOT Read April 23, 1946

I realize I live in a city teeming with romantic, historical street names. How sorry I feel for those

Fin

people who have to tramp on numbered streets, or alphabet, or even on tree and flower streets -

so I invite you to walk with me on some of the streets of my native City of Cambridge. Shall we

walk down Brattle Street first - noticing the beauty of the curves of that old highway as it follows

the banks of the Charles River, the street laid out by the first dwellers in Cambridge as the easiest

path toward Watertown? Brattle Street was named for General William Brattle - a Tory, who lived

in one of the lovely old houses known as Tory Row, many of which still lend graciousness to the

street. In our imagination we can see the scarlet-coated, rapiered figures walking up and down on

Ne

red-heeled shoes offering the hospitality of their snuff boxes to the friends they meet, or with their

Check

ladies, gowned in hoop skirts and wigs, driving in coaches to take tea with one another, before

and L

they were forced to flee the country in the Revolution.

Then we might turn up Sparks Street, named for a former President of Harvard, and dwell on the

Pre

idiosyncrasies of the President's wife, whose form of punishment for her daughter was, with each

misdemeanor, to take a tuck in her skirt, and, as in those days the mere sight of an ankle caused

Public

consternation, you can realize, that as the errors accumulated, and the skirts of the unfortunate

make

culprit rose higher and higher to the knees, what a confining life the young damsel must have led.

From Sparks Street to the next street is a short distance and I remember how a stranger, riding in

the horse car, inquired of the driver what the name of the street was at which she wished to alight,

describing it as a street bearing a noble name, and how he immediately replied "You mean

Buckingham, Ma'am."

Viewer Controls

Toggle Page Navigator

P

Toggle Hotspots

H

Toggle Readerview

V

Toggle Search Bar

S

Toggle Viewer Info

I

Toggle Metadata

M

Zoom-In

+

Zoom-Out

-

Re-Center Document

Previous Page

←

Next Page

→

[Series III] Cambridge

| Page | Type | Title | Date | Source | Other notes |

| 1-21 | Journal Article | Harvard Square in the 'Seventies' and 'Eighties' / Lois Lilley Howe | Read 1/25/1955 | Cambridge Historical Society Proceedings, v. 30: Papers Read During the Year 1944 | Annotated by Ronald Epp |

| 22 | Website | The Romance Of Street Names In Cambridge / Frances H. Eliot | Read 4/23/1946 | web address no longer accessible | - |