From collection Creating Acadia National Park: The George B. Dorr Research Archive of Ronald H. Epp

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

Search

results in pages

Metadata

[Series III] Harvard University-Cambridge & Harvard Square

Harvard University:

Cambridge Hanardsquare

MEMORIES OF NINETEENTH-CENTURY

CAMBRIDGE

BY LOIS LILLEY HOWE (1864-1964)

Read January 22, 1952

ONE of my earliest recollections - I cannot date it - is that I asked some older member

of my family if it was probable that I should be alive when 1900, the new century, came in.

I never imagined that I should live for more than fifty years in that century. My memories of

my early years in the nineteenth seem to be as if I lived in a different world.

was born in a college town where life was as simple as life in a village. The professors and

instructors in the college were all friends. Very few people had horses and carriages; the

horse cars were sufficiently convenient.

The house where I was born was old-fashioned, with very little essential so-called modern

plumbing. There was no pantry sink in what we called the "china closet," but there was a

butler's tray in which a dishpan could be put for the "second girl" to wash dishes. My

mother washed the breakfast cups and the silver in a dishpan on the diningroom table after

breakfast.

The kitchen sink was a large, low soapstone affair something like a glorified horse trough.

There was a double-oven range, in front of which meat was rosted in a "tin kitchen" -

much more delicious than a roast baked in an oven. This range also heated a large boiler, so

that there was always plenty of hot water, for we had set basins and hot and cold water in

many bedrooms.

The kitchen chimney must have been very old, for on the other side of it, in the so-called

"wash room," was a Dutch oven and beside it a huge built-in copper wash boiler to boil the

clothes which were washed in old-fashioned wooden tubs. There was also a wonderful

drying room opening out of this wash room, or back kitchen, which could be used in winter

or in stormy weather. It was a marvellous place to play in, having frames of wooden bars

which ran on rails and which could be pulled out when desired. It was heated by a little

stove in the cellar.

59

Beyond this wash room a passage led to a long ell between house and barn. In this was the

study, built for James Russell Lowell when he became Professor of Belles Lettres and lived

with my father and mother before his second marriage. It proved very useful for several

generations of students later It had an outside door and a chimney and a soap-stone

Franklin stove which did not wholly mitigate the winter climate. Beyond was a shed with

slatted blind doors and then the stable, called a barn, making a courtyard, in the middle of

which was a magnificent elm tree.

Cambridge Historical Souety Proceeding 34 (1952) : 68-75

I can just remember when there were horses but they had been given up and all that

remained of that glory was a fine old carriage in which I used to play - and, in the second

story, the empty hayloft and a pigeon house which my brother and his friends converted

into a club room. Later I had a studio in the summer here.

We kept a cow for many years. The first one I remember was a Kerry cow, something like a

bovine Dachshund, long and low. She once got stuck in a ditch on the edge of the woods not

far away. Her successor was a wanderer, always getting out of her pasture up the street. So

she had on one horn a large wooden tag marked "E. Howe."

Of course, the cow had to be milked and the man who milked her and took her out to

pasture in the summer also took care of the furnace and blacked my father's boots. These

were tall high boots pulled on with considerable difficulty with boot hooks. The tops were

concealed by his trousers. The process of pulling the boots on was usually done after

breakfast in the diningroom. There was also a boot jack to take them off which was kept in

a closet in the back hall.

The milk was put into wide, shallow milk pans and kept in what was known as the "milk

cellar," a room in the cellar with a cupboard which opened into a well close to the north

wall of the house. This "milk room" was paved with brick and had a sort of grave in the

centre with a trap door, to keep extra ice.

There used to be a barrel of soft soap in the cellar, too, but I have no knowledge of the

mystery of its being made. And there was always a large salt cod fish hanging up

somewhere, ready for use for Saturday's dinner of boiled salt cod and mashed potato -

and, of course, anyone could pinch off flakes of salt cod and eat them.

When I became old enough to take responsibility [sic.] I used to lock up

60

at night. There were six or seven doors to be fastened, all with bolts. Of course, that did not

count the bulkhead door from the cellar to the yard - just right to slide down!

It was a very inconvenient house in many ways, needing much domestic help. There was a

long hall between the kitchen and diningroom but there was a slide which opened into the

china closet. In the corner of the house was the "inner china closet" in which jellies and

preserves were kept. What visions this calls up of preserve and jelly making! My mother

would have scorned canned fruit! Back of the inner china closet and opening from the back

hall opposite the kitchen door was a large storeroom with shelves all around it. On the top

shelf I remember a row of empty blue and white ginger jars.

There was a marble slab on which to make pastry, and during some period of financial flush

I remember the building of a large refrigerator between the storeroom and the inner china

closet. The ice man climbed up several steps in the storeroom and put the ice in. This

refrigerated a large cupboard in the other closet with many shelves. It was the most

modern thing in the house!

The furnace was quite inadequate but there were several handsome round registers on the

first floor and one register in the second, and there were fireplaces in the bedrooms.

In the third story, the upper hall, lighted by a sky-light was very fascinating and there was

a wonderful and unusually large rocking-horse there. One little room with its own sky-light

bore upon the door a large sign "Oxford Museum," but the collections were not very

interesting - a few desiccated butterflies, some birds' eggs, lucky stones and shells. I used

the room for a work room for many purposes of my own.

The two parlors were very handsome and had windows in embrasures with shutters. The

only thing I never liked was the staircase - straight and uncompromising, somewhat

commonplace but not pretentious. Probably if I were altering the house now I should leave

it alone. But I always longed for a handsome staircase like that in the Batchelders' house

next door and I worked out in my mind how it could have a turn near the bottom and how

there would be headroom for the change. This idea had a curious effect on my life

afterward.

There was about an acre of land which provided much entertainment. There were two more

wells, relics of an old farm house. Neither

61

could be investigated but one had a hole under the flagstone top through which a stone

could be poked, affording the noise of a good subterranean plunk.

On the south side of the house there was a swing between two trees and a ladder like a

fruit-picking ladder up which you carried the rope, then put your foot in the loop and swung

off. There was great competition as to the highest rung to swing from.

This was near a lawn, called the croquet ground, which made a very small tennis court

later. To the north of that was the clothes yard and a group of pine trees known as the

playground. Beyond was the garden - a real garden, an old-fashioned box parterre with, on

either side of it, vegetable gardens and currant bushes. (Financial helps - five cents a

hundred for picking off currant worms!) There were also pear trees and grape vines. The

Batchelders' yard next door had more climbable trees, as I learned when they had a young

cousin from Baltimore visiting them.

The house I was born in is still standing on the corner of Oxford and Kirkland Streets, for

this town I speak of was Old Cambridge, Massachusetts, as I knew it in the '70's and '80's.

The house has been modernized - we called it Number 1 Oxford Street - and the lovely

garden vanished long ago. The so-called playground was seldom used as such except on the

triennial visits of my married sister who lived in Ohio. Her oldest daughter was a year older

than I, so my nieces and nephews were contemporaries. Their visits were memorable.

Sometimes we were taken for the day in an open carriage to Chelsea Beach, a big lonely

beach of which I wish I could remember more. The world knows it now as Revere Beach.

But that playground was the place where my brother, four years older than I, celebrated

the holidays - Fast Day, the first Thursday in April, Bunker Hill Day, the Seventeenth of

June, and the Fourth of July. I had to be content with little packages of torpedoes but he

not only had firecrackers but a little cannon (in stage language "a practical cannon") and

powder. What he did with this was to shoot the dentist in effigy, the effigy being made of

old magazines and the ammunition of old dental instruments. I suppose he must have

wearied of this and so he took down the empty ginger jars of which I have spoken and

demolished them. My mother was much displeased. I have often won-

62

dered if any of them was like the one Frank Bigelow found which was worth $2,000.00.

I can just remember when there was a long low building on the Delta across Kirkland

Street. This was the foundation of Memorial Hall and I was always absorbingly interested in

its construction. After the hall was built there was at its east end a deep sandpit in which I

sometimes played, looking up the high straight wall to the top of the tower. In this pit was

built the cellar of Sanders Theatre. While the theatre was being built I clambered all over it

and the workmen called me "the little superintendent."

But the first thing that I remember of what happened in the outside world was that there

was a great fire in Chicago. This was stamped on my mind by the fact that one of my

cousins was "burned out." He brought his family to my uncle's in Cambridge and I was

taken to meet the three little cousins I had never seen. This meeting was a great

disappointment to me from which I never fully recovered, though I never told anyone about

it. I peered anxiously under their chairs but their shoes and stockings were all whole. I had

supposed, of course, they would have holes burnt in them.

It was a year later, on a Sunday morning in November, 1872, when I was eight years old,

that my brother came into my nursery and pointed to a lurid glare in the sky. "That," he

ofi72

said, ""is the big fire in Boston that started last night and is still burning!" My father was ill

at the time and his office was in a building in the path of the flames It was proposed to

Fire

blow up that building and the key of his safe could not be found. Even the small child of

eight felt the anxiety of the family. Fortunately it was decided not to blow up the building.

There was at the time an epidemic known as the epizootic which had attacked all the

horses. The Cambridge fire engine was dragged in by Harvard students, who, you may be

sure, did many deeds of derring-do. There was a group of young cousins in college at that

time and they had many stories to tell.

I was never taken to see the burned district, which stretched from Washington Street down

to the harbor. Of course, my brother and his friends explored it and he brought home a

large chunk of melted-up cups and saucers he had found in the ruins. This was one of the

chief exhibits in the "Oxford Museum."

63

I cannot remember how old I was when I saw for the first time a silver quarter of a dollar. I

was used to paper ones like small one-dollar bills. This beautiful coin was shown me by the

father of a little girl with whom I was playing. The encyclopedia says that, after the Civil

War, specie payments were resumed in 1879, but I saw that silver quarter some years

before that. I remember also the large copper two-cent pieces and the small three-cent

pieces of silver.

My father's sister, my Aunt Mary Howe, taught me to read. I cannot remember when this

was, only I used to set my dolls in a row and teach them to spell from an old primer I had.

Sometime when I was about five or six years old I began to go to school to Miss Mary

Olmsted. Kindergartens had not been invented and I cannot remember what we studied or

learned except that we worked mottes on perforated cardboard. I may have learned the

multiplication table and the difference between Roman and Arabic numerals. We certainly

stood up in class to recite something.

(1826-96)

This school was held in the diningroom of the house of Professor Francis J. Child. We used

the diningroom chairs as desks and sat on footstools in front of them. We helped Miss

Olmsted, whom we adored, to put away books (what books, I wonder?) under the serving

table when school was over.

No servants or families escorted us to school. My cousin Agnes Devens, Mattie Sever,

Winnie Howells, daughter of William Dean Howells, and I walked to school together and

there met Helen Child, her two younger sisters, Susan and Henrietta, and Florence Farrar

and Edith Cushman. It is something to remember, Mr. Francis J. Child working in his rose

garden!

There were no new houses on Kirkland Street. We knew who lived in every one. On Kirkland

Place where Miss Fowler's garden now is was Peirce's Pond where we learned to skate and

where there were goldfish in the summer. I went to catch some once and Professor Peirce

came out to catch me but I stood my ground (what I had to stand on), and when he found I

was the daughter of a very old friend he forgave me.

Francis Avenue was a private drive up to the Munroes' house somewhere near where Bryant

Street now is. There was an open field from there to Kirkland Street. About opposite this

when I first went to school were the blackened ruins of Parkman Shaw's house which had

64

burned down one summer night, all the neighbors coming to help.

Irving Street did not cross Kirkland Street. Between it and Trow-bridge Street was a lovely

bit of woodland where we could pick wild flowers in the spring. The driveway to the

Nortons' house came about where the northern part of Irving Street now comes.

The Norton girls did not come to school with us; in fact, they did not come home from

Europe for a good while after I began to go to school. However, we soon became old

friends. It was pleasant to walk up between the Childs' house and the house of Miss

Ashburner and over the fields to Shady Hill.

Somehow, my memories always seem to be of spring and summer. We always had a May

Day festival. But when I speak of the Norton place I remember being allowed to go coasting

down from the front of their house on a winter evening. A big boy named Will Winlock had a

double-runner - a big board carried on two sleds. This preceded the toboggan and we

thought it much fun.

Norton's woods were real woods with a trail through them. I'm more apt to think of

approaching them the other way, through Divinity Avenue. Back of Divinity Hall was an

open field that led to Norton's Pond, a dark pool with a brook running through it and a

board fence on the Norton side of the brook. A plank walk crossed the brook on one side

and led to a hole in the fence. This pond must have been somewhere near where Bryant,

Irving, and Scott Streets now lie. This was easily reached from Oxford Street - or from the

Severs' house on Fris-bie Place, the yard of which ran through to Divinity Avenue. This was

one of my favorite playgrounds. I was so much younger than anyone else in my family that

I was rather a lonely child. There were the three Sever children, Mattie, my sworn friend,

and her brothers, George and Frank.

Then there was the Agassiz Museum to visit. We were always allowed to go there and

nobody knew the rites we performed - quite gently - with tails and noses of those

skeletons of prehistoric animals which are probably now discarded.

Also I had to superintend the building of the Peabody Museum. My aunt, Mrs. Arthur

Lithgow Devens, lived on the corner of Oxford and Everett Streets, close by Jarvis Field. We

could watch baseball games on the field from her windows. Near Jarvis Field was a huge

and

65

terrifying old willow in a place always called uThe Ditch. I have no doubt it was one of the

last remains of the original "Palisade."

My aunt's younger daughter, Agnes, was only a little younger than I and we naturally did

many things together, but I was more interested in the Severs. I have been told that I once

said, "Aggie and I are very different. We have different views." Which was very true.

we went to Miss Olmsted's School together and when Miss Olmsted married we both went

to Miss Sarah Page's School on Everett Street - next door to my aunt's.

Here was a real school for girls and boys and real work - history, geography, drawing maps

- how I loved that! - long sums of "Partial Payments" on my slate, French lessons from

Madam Harney, learning to repeat poetry.

used to be furious with the pupils who could

never get anything to repeat beyond "Old (Ironsides at anchor lay" and Tennyson's "Brook"

(which they seemed to emulate, going on forever), both of which they found in the third

reader. So I hunted up poems at home. I ought to have consulted my sister Clara, who

would have given the best advice. But I only remember one piece of poetry that I learned

and that I have never forgotten, though I still harbor a grudge against the young teacher

who was amused at me. I imagine I 'was funny at twelve years old declaiming "How well

Horatius kept the bridge in the brave days of old."

Our parents thought it wise for "Aggie" and "Lolo" to go on Sunday afternoons to see

Cousin Mary Howard. Poor Cousin Mary, I have her sampler, made in 1792, but when I

knew her she was blind and really poor. She was a cousin of my grandmother's who had

fallen upon evil days and was a beneficiary of some fund for aged women. She was nearly

one hundred years old. She used to tell us how her father had held her up to see General

George Washington when he came to Boston in 1790. I do not think there are many people

now living who can remember anyone who saw George Washington. I used to say that that

was my greatest event. My sister Clara had been held in William Makepeace Thackeray's

arms when Uncle James Lowell brought him to our house when she was a baby. But my

sister Sally had the most wonderful thing to tell. She had been to a reception at the White

House and had shaken hands with Abraham Lincoln.

Agnes and Mattie and I all went to Sunday School together, too, and

66

we were in Miss Edith Longfellow's class. Of course, we adored her and felt very sad to have

her marry and leave us. She was married January 6, 1878. I take the date from a little New

Testament with my initials on it in gold. She gave us each one, and more than that, all

through that December when she was getting ready to be married she had our class come

once a week in the afternoon and make scrapbooks for poor children. I seem to remember

we worked in the southeast room on the second floor of Craigie House. The spring after she

was married she had us come to Boston and spend the day with her and go to ride on the

Public Garden swan boats.

Three years at Miss Page's fitted me for the Cambridge High School. I had to take

examinations for entrance. That was in June and must have been 1877. They were held in

the old Harvard Grammar School, a wooden building long since demolished, on Harvard

Street somewhere beyond Prospect Street. I walked down there by myself every morning

for three days, and I never shall forget what a pretty street Harvard Street was then. Then I

began to go down to the High School on the corner of Broadway and Fayette Street. Where

the Rindge School, the Library, and the other schools are were open fields. I do not believe

the modern high schools in this part of the world begin their first course with English

History - a review for me, as was also reading "The Lady of the Lake." But Latin was new

and so was algebra - and the minus sign still has an unpleasant effect on me.

It must have been about this time that my oldest brother said at dinner one day, "I see that

man Bell, who married Mabel Hubbard [the daughter of our neighbor, Gardiner Greene

Hubbard] has patented that invention of his which he claims will make it possible for people

to talk to each other at a distance." "Yes," said my father, "it may be very useful if it proves

to be practical." I have been told that Mr. Hubbard afterwards became bankrupt and his

creditors allowed him to keep a lot of worthless stock he had taken in his son-in-law's

invention. Electricity was still in its youth. Very little was known about it, but scientists

were working on it.

In my second year at the Cambridge High School I was in a class in what was called

"Natural Philosophy," a mild form of Physics. I seem to remember vaguely learning

something about specific gravity and that water will rise to its highest level if confined, and

something about

67

frictional electricity. I don't know why I have always remembered that we were told that if

a wire with a strong electric current was cut or broken the current would for a few seconds

continue to flow from one end of the break to the other. It would make a very brilliant light

for a few instants and then its heat would burn off the ends of the wire. If any means could

be found of preventing this destruction of the ends, this brilliant spark might be used to

give light. On this theory the arc light was constructed, which was for a long time used for

street lighting. Perhaps some of you remember collecting the broken scraps of carbon left

by the linemen when they made repairs.

More wonderful, however, was something which had been lent to the teacher to show us -

a little glass ball with a wire burning and shining in it - the first incandescent bulb, just

invented by a man named Thomas Edison. (I often wonder how the teacher electrified the

wire.) Now you are not to suppose that electric light and telephone began at once to be of

use. Mr. Edison's lamp was invented in 1879, the telephone several years earlier. In 1890,

much scared, I made my first call on a telephone! And when we built our present house in

1887 we did not put in electric light - it was not cheap nor was it considered safe.

Agnes did not go to the High School, and Mattie Sever did not go either there or to Miss

Page's School. About this time her father inherited a house in Kingston and for several

years I made a visit there every summer. This house is one of the finest old New England

houses in existence and its beauty sank into my heart and mind at once - never to be

forgotten. It was full of beautiful old furniture, too.

Very few people in Cambridge went away for the whole summer but the Devens family

always did, and after the Severs began to go too my summers were rather lonely, But there

was a place where I often made a visit, this time with my mother. This was (Canton)

Massachusetts. My grandmother's sister, whom I can just remember, married the son of

Paul Revere. He had developed the Revere Copper Company on the grounds of which was

the place where Paul Revere cast his bells. Here my real hostess was my father's cousin,

Miss Maria Revere, just like a very dear aunt to me.

We went by train to Canton Junction and from there took "the little car" which was like a

hack on low wheels. This was drawn by a horse on a spur track which led to the "Works."

From there we walked across

T.W. Ward S.C Contor

68

residesce

the Neponset River on a bridge and up the drive to the house. This was built on a side hill

and the diningroom and kitchen were in the basement, but the diningroom door opened out

into a grove of real forest trees. Breakfast and dinner were eaten there but supper was

brought upstairs to "the little parlor" where it was eaten by candelight. There was neither

gas nor electricity and to me it was marvellous and romantic.

Then up the hill was where Cousin Maria's brother, Cousin John, lived with his family, which

included Susie (now Mrs. Henry B. Chapin), about my own age, and her younger brother,

Ned.

What fun it all was and how interesting was the Copper Yard with its furnaces and

machinery and in the middle a great barn, very necessary, but interesting mostly because it

sheltered a donkey named "Peggy" and a donkey cart for our use. We used to drive up to

the village and buy chocolate drops of Miss Chloe Dunbar, and to the paper box factory

where were sold nests of boxes with pretty pictures on the covers.

The little cousins who were burnt out in Chicago lived in Holyoke Place for a time and then

in an apartment in Bulfinch Place in Boston - the first apartment I had ever seen with the

first elevator I ever tried to run> Although only about twelve years old I was allowed to go

into Boston by myself to spend Saturdays with them. The Broadway horse car took me to

Bowdoin Square close to Bowdoin Street. There were other cars from Harvard Square up

Main Street. A man came up to the car at Green Street with an extra horse which he hitched

on to help pull the car up the hill! Shoppers generally disembarked at Temple Street and

walked over the hill to Park Street past a frowning granite reservoir on the west side of the

street. My father, who was one of the directors on the street railway, once told me that the

long pile causeway and bridge, nearly a mile, where no fares changed, was a great liability.

There was always the chance of the drawbridge being open to delay the passage, and there

was that train crossing from the Boston and Albany which is still bothering surface cars.

If we were going to the mountains or the north shore we took a car which went on

Cambridge Street. For the first part of the way this was quite interesting. Between Baldwin

Street and Inman Square on the north side of the street was Hovey's Nursery with a high

board fence over the top of which were tantalizing glimpses of trees. Opposite were a

number of very handsome and, to me, interesting houses. (Houses

69

always attracted me.) They had flat roofs and there were low brick garden walls along the

street. The rest of the street was commonplace with an occasional dwelling house, but in

Boston the cars arrived at a very slummy place and there were three stations close together

on Causeway Street where the North Station is now - the Lowell, the Eastern, and the

Fitchburg Stations. The Boston and Maine was in Haymarket Square.

At the High School I was fitted for Harvard College and took the examinations for entrance.

A group of ladies who were interested in the higher education of women had formed an

organization which arranged that women could take the entrance examinations for Harvard

and receive a certificate that they had done so. These ladies were the precursors of those

who started Radcliffe. I think I was one of the very last girls who took the examinations

under that organization and had my name in the College Catalogue.

My "preliminaries" were taken up in a big room at the Botanical Garden in June with dear

Mrs. Asa Gray bringing in lemonade for us. My finals were taken with the rest of the girls in

my class (who almost all went to "The Annex" afterward) in the Garrets' house, now called

"Founders House," on Appian Way.

Those five years at the High School were filled with much pleasure, in which I was more

interested than in the School. Though I pretended that I was sorry to leave school I realized

that I was giving up something very precious in the friends I had made there. The old

friends were never really forgotten, but new interests and broadening experience made

new ones of greater importance.

There was in Cambridge, on the other side of the Common, a set of girls that I never went

to school with but whom I gradually came to see socially, and among them were Marion and

Alice Muzzey. I was between them in age and I became very intimate with them in their

house on Coolidge Hill with its yard going down to Mount Auburn Street. Alice was my

dearest friend. Their father died about a year before mine did and they went to Buffalo to

live with their brother. I visited them there twice and stopped on the way home in Auburn,

New York, to see Agnes who had married Thomas Mott Osborne. I wrote a weekly letter to

Alice from the time she left Cambridge for more than thirty years.

The summer after I left school a cousin who was a chemist turned up.

70

Our house was always open to all sorts of relations and my mother was almost like a

grandmother to all her nieces and nephews. This young man, aferwards an expert on

concrete, had with him a camera and a tripod and "these new dry plates," and I have a

photograph he took (very bad) of the whole family sitting on the lawn! Up to that time, and

for many years afterward, it was tintypes that we had taken (when we could afford it). I

have a funny collection - but how soft and pretty they are.

I had no desire to go to college, but I felt I must do something. After family consultation

with Mrs. Susan Nichols Carter, an old friend of the family and the head of the Art School at

the Cooper Union in New York, I went to the school of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in

September, 1882, to study drawing and painting and design.

Here was a new life opened to me. In the first place, I had to go to Boston every day. A new

route had been established; the cars did not all go to Bowdoin Square - some of them

turned off and went through Charles Street to Park Square. Shoppers walked across the

Common instead of over the hill. At Park Square was the Providence Station with its high

clock tower where is now the Hotel Statler.

There was a special car at 8:15 that ran on Broadway and was patronized by a number of

very interesting people who taught in schools in Boston. There were Mr. John Hopkinson,

who kept a very fashionable school for boys, Mr. Walter Deane one of his assistants, also

Mr. Volkmann who afterward founded the Volkmann School, Miss Elizabeth Simmons, one of

the most brilliant and interesting women I ever met, sometimes Miss Catherine Ireland in

whose school she taught, and Miss von Seckendorff who taught German in that same school

- and afterwards gave me private lessons in German. French I had had at Miss Page's and

also rather casually in High School. For company near my own age was Fanny Ames, now

Mrs. Mallinson Randall, younger than I but never to be forgotten, going in to Aliss Ireland's.

I left the car at Boylston Street, a street then composed almost entirely of houses in which

"nice" people lived. There were the two hotels, Hotel Berkeley and Hotel Brunswick, but on

the corner of Berkeley Street opposite Hotel Berkeley was the very handsome building of

the Young Men's Christian Association. Of course, on the other side of Boylston Street were

the Natural History Museum, the Rogers Build-

71

ing of the Institute of Technology, and the Walker Building. I think the latter was not there

in 1882. 1 think the Lowell Institute of Design had a small low wooden building there. My

idea was to go to that later but I came to scorn it.

Trinity Church was just built, and where the Sheraton Plaza now stands was the Art

Museum. In front of it was a dump. Where the Public Library now stands were two thin city

houses with marble fronts.

Horse cars, blue and green ones, ran up Boylston Street and all around the square to

Dartmouth Street and then through and out Marlborough Street.

The school was in the basement of the Museum and in the attic, where was the life class,

and also in a lecture room up a winding staircase among the skylights. Beginners, after

learning in the basement to draw very large hands and ears and eyes, were promoted to

work in the galleries of the first floor, where most of the objects of interest were casts of

famous statues.

There were two instructors, Mr. Otto Grundmann, imported from Europe, and Mr. Frederick

Crowninshield, who had a brick studio in the back yard where he made stained glass

windows. He was much more interested in the students than Mr. Grundmann and did a

great deal for them. He had had a class in History of Decoration and this class had become

so interested in Egyptian art that they had with their own hands decorated in the Egyptian

manner a room in the basement which was used as a lunch room. Here a woman came

every day and served hot cocoa for a small sum. Every day I brought in bread and butter

and a raw potato. On the latter I cut my initials and she baked it for me.

Of course, we all had special seats at the long tables. I sat with my classmates, called by

Mr. Crowninshield "Infants." I made a group of friends and we had many merry times

together - always dashing out to Trinity Church to weddings when we saw the awnings

out.

It was probably Mr. Crowninshield who engineered having Mr. - afterward Sir - Hubert

Herkimer come and speak to us. He was a distinguished English artist. I can't remember

anything he said except that a new process had been discovered by which drawings and

photographs could be cheaply reproduced, and it was possible that we might at some time

be able to have illustrations in our morning papers. He never imagined that they would be

telegraphed around the world.

72

I found that Mr. Crowninshield had arranged for a summer school in Richmond,

Massachusetts. It had had one or two sessions and it seemed to me it was very important

for me to go. So it proved, though not in the way I expected. My family consented, and

although my brother had died early in June after a long illness, I started off under the

patronage of two elderly ladies - at least I considered them elderly. They must have been

between forty and fifty! I thought them too old to paint.

Never shall I forget that journey through the valley of the Westfield River! Ayong drive over

the hills from the Richmond railroad station to "Kenmore" brought us to the old house

which Mr. Crowninshield had found, It was and is a remarkably fine eighteenth-century

house with a wide hall and grand staircase.

Two of the four rooms on the first floor were furnished as parlors with straw cushions. All

the other rooms were dormitories, in one of which at the back I was quartered with some of

the older ladies and Alice Hinds, who was not only one of the important older students of

the school but Mr. Crowninshield's assistant in his studio. She it was who was keeping

house, and another older student, William Stone (familiarly known as Billy Rocks) took care

of the very necessary horse and wagon; for we were many, many miles from everything

except a farm house directly across the road where were two diningrooms and a kitchen

and some domestic help.

was rather disappointed not to be put at the dining table with the younger members of the

party but placed with the old ladies. However, with them were Dr. and Mrs. Edward

Emerson of Concord and their children, and that certainly was a privilege. He was the son of

Ralph Waldo Emerson and was desirous of giving up his chosen medical profession for that

of artist.

There were only two "Infants" besides myself and those not well known to me. The other

students besides the "old ladies" were from the very upper class at the school. Among

others were Frank Benson of Salem and Joseph Lindon Smith, both headed for Paris, and

I

some other young men. began to realize that there were many respectable and socially

agreeable young men to whom Harvard College was no attraction. The queens of the whole

establishment were Helen Hinds (Alice's sister), May Hallowell of West Medford, and Lizzie

Schuster of Brattle-

73

boro. They had some secret plan of a play they were to give. There were murmurs of it but

it never came off.

I was odd man out and belonged with nobody but did not seem to mind it, except that they

were planning to have a dance on Fourth of July. They had a piano, though no other

furniture except beds. My brother had died so recently that I felt as if I could not go to that

dance, but I could not think how to get out of going.

On the Fourth of July someone put up a hammock and Helen Hinds got into it and began to

swing. Out came a staple and down she fell and banged her head badly. Dr. Emerson said it

was only a slight concussion but she must keep quiet for several days, and neither she nor

the girls who shared her room could go to the dance. Of course, these two girls wanted to

go, and so Helen's sister was expected to give up her bed to one of the other girls and I

offered to give up mine. It was such an opportunity for me! Not much to do, was it? The

result was that I not only ceased to be a nonentity but, because I was considered so

unselfish, I was taken up by the most desirable girls in the community and formed

friendships for life. Two of those "girls," now over ninety are still my intimate friends.

In my last two years at the Museum School I was in a new department, the Decoration

Class. Here we had an architect, C. Howard Walker, for a teacher - one of the most

interesting and inspiring. He had travelled extensively in Europe and he put at our disposal

all

his photographs and sketches. Another door opened wide. I began to feel that I wanted

to be either an illustrator or an architect. I was told that if I learned to draw and paint I

could easily become an illustrator, but as a woman I could not be an architect. Mr. Walker

said I should have to learn to swear and that most of the time I should think my occupation

tedious.

After four years at the Museum School I tried doing some work at home for a year. My

father had been ill a long time and he died in January. He wished my mother to sell our

house and the land and build a smaller house somewhere.

We were fortunate enough to sell the house at once to the Reverend Francis G. Peabody. (It

is now known as the Peabody House.) Of course, his brother Robert, a very distinguished

architect, superintended the remodelling of it. Mrs. Peabody felt as I did about the staircase

and

74

wanted to have it turned. He said it could not be done and she said Miss Lois Howe had said

it could be. He found I was right - so he always was interested in me!

It was heartbreaking to leave the house and very difficult to find a location for a new one,

but we suddenly heard that Mr. Charles Choate was giving up his place on the corner of

Brattle and Appleton Streets and we were able to buy the asparagus bed. My aunt, Mrs.

Devens, sold her house on Everett Street and bought the corner lot next to us.

Cabot and Chandler were the architects of our house and I spent every minute that I could

in it while it was being built and then said, "This is what I want to do!" So I went to see

President Walker of the Tech and asked him if I could come into Tech on a six years'

certificate of entrance to Harvard College, to which he agreed)

Lewis Carroll's book "Sylvy and Bruno" came out about that time with its fascinating jingles

which we were all imitating, and one of my friends wrote this:

I thought I saw an architect

Climb up the Tech's high stairs.

I looked again and found it was

A lamb midst crowds of bears.

Poor thing! I said. Poor lonely thing,

I wonder how she dares!

And I was the only girl in a class of sixty-five men and one of two girls in a drafting room of

ninety. The other girl, Sophia G. Hayden, was ahead of me in class. She never did anything

for me, but Mr. Francis H. Chandler, the architect of our house, became the new head of the

Department of Architecture and that was a help.

I had just begun to go to Tech when our neighbor, Miss Mary Blatch-ford, came to call.

When she heard what I was doing she said her nephew, Gardiner Scudder, was going there,

that he walked over to Allston and took the train in every morning. She was sure he would

like to have me go, too. Gardiner was much younger than I, too young for Harvard, they

thought, so he was having a year at Tech. So Miss Blatch-ford put it through, and every

morning Gardiner and I walked to Allston and took a train under the big railroad bridge. We

got out when the train stopped before crossing the Boston and Albany road near where the

Trinity Place station now is. We got through a hole in the fence

75

and were very near the Tech. This was the beginning of a very happy friendship lasting,

alas, only a few years, for Gardiner died very young.

From St. James Avenue to Columbus Avenue was all railroad tracks - like the great space

along Boylston Street now - only on the street grade.

Next year I used the horse cars to go to Boston. From our parlor window we could see the

car coming down Brattle Street and run out to get it. If I was late for my usual car old Jerry,

the driver, waited for me. The cars from Harvard Square to Boston had been electrified and

we always had to change at the Square - in the open - in every kind of weather.

I took only what was called a "partial course" in architecture - two years - but I

got a job in the office of Francis R. Allen of Allen and Kenway.

All eyes were turned on Chicago where was being built the great Columbian

Exposition which had a marvellous architectural effect on the country. Mr. Robert Peabody,

1893

who was one of the Committee of Architects planning the exposition telegraphed me to

enter a competition for the Women's Building at this Fair. I told Miss Hayden about it. Mr.

Chicopo

Allen gave me leave of absence and we both went to work. She got the first prize and built

the building. I got the second prize, $500.00, and that meant I could go to Europe.

Expo

76

MOUNT AUBURN'S SIXSCORE YEARS

BY OAKES I. AMES

Read April 22, 1952

THE consecration of Mount Auburn Cemetery one hundred and JL twenty years ago last

September constituted a notable landmark in the history of landscape gardening as applied

to cemeteries. For the first time in this country a large burial ground was opened to the

public in beautiful rural surroundings in sharp contrast with the crowded and frequently

ard On The Charles

Page 1 of 4

BAHS Home I History Neighborhoods

Photo Collection

Brighton

Allston

Historical

Society

This article by Allston-Brighton historian Dr. William P. Marchione appeared in the

Allston-Brighton Tab or Boston Tab newspapers in the period from July 1998 to late 2001,

and supplement information in his books The Bull in the Garden (1986) and Images of

America: Allston-Brighton (1996). Researchers should, however, feel free to quote from the

material, with proper attribution.

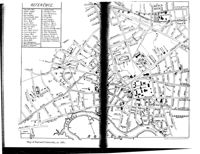

Harvard on the Charles

For the first nearly 300 years of its history, Harvard University was largely confined to the

area in and around the Harvard Yard near Harvard Square. Harvard was then a rather small

school. As late as 1869, it had an enrollment of barely 1100 students, and a faculty of a

meager twenty-four. Harvard spread to the banks of the Charles River only at the turn-of-

the-century as its enrollment and educational mission expanded.

So successful was the turn-of-the-century enlargement of the campus from a stylistic

standpoint---the predominant architectural medium being the neo-classical style---that

today's casual observer probably assumes that the university buildings on the river date from

the 18th rather than the early 20th century.

This successful integration of the old and new portions of the Harvard campus was a truly

great achievement, testimony both to the vision and energetic leadership of two great

Harvard Presidents, Charles W. Eliot and A. Lawrence Lowell, as well as to the great talent

of the architects the university commissioned to carry out this singular expansion program.

Prior to 1900, the Charles River shoreline east of Boylston Street (now John F. Kennedy

Street)---a district then known as Riverside---wa one of the least attractive areas on the

margin of the Charles. Prior to 1906, when a dam was built at the river's mouth to

permanently exclude the tides, the contracting and receding shoreline made the river's edge

unsuitable for anything other than commercial and industrial uses. Riverside had accordingly

developed into a district clogged with unattractive commercial structures---an assortment of

wharves, coal yards, storehouses, even a power plant.

http://www.bahistory.org/HarvardCharles.html

7/31/2018

vard On The Charles

Page 2 of 4

This was also true to a lesser extent of the less developed Allston-Brighton side of the river,

where a coal company stood adjacent to the North Harvard Street Bridge, the wooden bridge

that then spanned the river on the site of the present Larz Anderson Bridge.

The first proposal for the development of Charles River shoreline by Harvard was advanced

in 1894 by the great landscape architect Charles Eliot son of Harvard's President Charles

W. Eliot. It was young Eliot's suggestion that Harvard immediately proceed to develop the

more than one hundred acres it owned on the Allston-Brighton side of the river.

This land had come to Harvard as a result of two late 19th century gifts. One of the parcels,

the Brighton Meadows, had been donated to the college in the early 1870s by the poet Henry

Wadsworth Longfellow and several of his Brattle Street neighbors. Learning that a group of

Brighton butchers (Brighton was then the regional headquarters of cattle and slaughtering

trades) were proposing to build a giant slaughterhouse, or abattoir, on the site that would

have spoiled their view of the southside meadows, these concerned property owners

purchased the acreage and presented it to Harvard. The second gift, Soldier's Field, was

deeded to the university in the 1890s by the banker-philanthropist Henry Lee Higginson

(founder of the Boston Symphony Orchestra) in memory of six Harvard classmates who had

been killed in the Civil War.

The first Harvard buildings constructed on the river's edge went up on the Allston-Brighton

shore in the 1897 to 1903 period and were athletic facilities. They included Carey Cage,

dating from 1897 (a structure only recently demolished). Adjacent playing fields and

wooden spectator's stands were also built. Then, in 1900, the handsome Newell Boat House

was constructed just west of the North Harvard Street Bridge, a work of Peabody & Stearns,

notable for its use of slate as a facade covering.

The next major Harvard edifice constructed on the south bank, dating from 1903, was the

massive Harvard Stadium, designed by the renowned architects McKim, Mead, & White.

This stadium, which seats more than 50,000 spectators, enjoys the distinction of being the

http://www.bahistory.org/HarvardCharles.html

7/31/2018

vard On The Charles

Page 3 of 4

world's first massive structure of reinforced concrete, as well as the nation's first large arena

for college athletics.

The oldest extant Harvard structure on the north side of the river is the Weld Boat House,

which lies just east of the foot of the Larz Anderson Bridge, and dates from 1907. Rowing is

Harvard's oldest organized athletic activity, going back to 1852. This handsome masonry

structure replaced a modest wooden boat house that boating enthusiast George Walker Weld

built for Harvard in 1890.

Harvard's adoption about 1910 of a new policy, requiring lower classmen to live in

university housing, provided the major impetus for the acquisition and development of the

Riverside acreage. It was hoped that this "House System" would foster intellectual

communication between students and junior faculty, who would also occupy these

handsome new dormitories. A. Lawrence Lowell, President of Harvard from 1909 to 1933,

carefully supervised every aspect of the large-scale construction project to which the new

housing policy gave rise.

As the Cambridge Historical Commission noted of these new structures on the Charles, their

architecture reflected "a conscious effort by the administration to extend the atmosphere of

the old Harvard Yard to a new South Yard and thus to symbolize the continuity of the

Harvard 'Collegiate Way of Life."

The first of the four Houses to be built facing Memorial Drive between Boylston and Flagg

Streets, Winthrop House, consists of two edifices, Standish and Gore Halls, both built in

1913. The latter structure is notable for its garden facade, recalling Hampton Court in

England. Winthrop Hall was designed by the architectural firm of Shepley, Rutan, &

Coolidge.

Next came McClintock Hall, built in 1925 and enlarged in 1930, a structure which has since

been absorbed into the modern Leverett House complex.

Then, between 1929 and 1930, two additional Houses were built on the river, anchoring the

eastern and western ends of this handsome. First came Dunster House, at the eastern end,

then Eliot House at the corner of Memorial Drive and Boylston Street, opposite the Weld

Boat House. Both were designed by Coolidge, Shepley, Bulfinch, & Abbott.

The Harvard School of Business Administration, founded in 1908, had in the meantime built

a magnificent new complex on the Allston shore east of the Larz Anderson Bridge on a

parcel of land that had once been the farm of Emery Willard. Dating from the 1925 to 1927

period, this handsome grid of ivy-covered Georgian Revival style buildings, with the neo-

classical George F. Baker Library as its focal point, faced the river. The Business School

complex, like neighboring Harvard Stadium, was designed by McKim, Mead, & White.

Prior to 1913 the only bridge across the Charles in the vicinity of Harvard had been the old

wooden drawbridge at North Harvard Street, on the site of Great Bridge, the first bridge on

the basin, built in 1662. The old Harvard Street Bridge was replaced in 1913 by a handsome

neo-classical brick and concrete span designed to blend with the architecture of nearby

Harvard buildings. Larz Anderson, U.S. Ambassador to Belgium and an 1888 Harvard

graduate, furnished the money for the structure, which was named in memory of his father,

Nicholas Longworth Anderson of the Harvard class of 1858.

http://www.bahistory.org/HarvardCharles.html

7/31/2018

vard On The Charles

Page 4 of 4

The other Harvard area bridge, the Weeks Foot Bridge, was built in 1926 while the Business

School was under construction with the object of linking together the two halves of the

campus, which the Charles River now SO conspicuously divided. It was named for U. S.

Secretary of War John W. Weeks, a former U.S. Senator and Mayor of Newton. The money

for this handsome structure, also neo-classical in style, was donated by thirteen friends and

business associates of Weeks. It too was designed by McKim, Mead & White.

Thus in the 1897 to 1931 period Harvard University completely altered the appearance of

both sides of the Charles River near Harvard Square, thereby transforming one of the ugliest

stretches of the Charles River into what most modern observers would agree is one of its

greatest attractions.

BAHS Home I History I Neighborhoods I Photo Collection

http://www.bahistory.org/HarvardCharles.html

7/31/2018

UNIVERSITIES AND THEIR SONS

HARVARD

UNIVERSITY

ITS HISTORY, INFLUENCE, EQUIPMENT AND

CHARACTERISTICS

WITH

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES AND PORTRAITS OF FOUNDERS,

no

BENEFACTORS, OFFICERS, AND ALUMNI

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

GENERAL JOSHUA L. CHAMBERLAIN, LL.D.

Wards.

EX-PRESIDENT OF BOWDOIN COLLEGE AND EX-GOVERNOR OF MAINE

to

SPECIAL EDITORS

Approved by Authorities of the University

HISTORICAL

BIOGRAPHICAL

WILLIAM ROSCOE THAYER, A.M. (Class of '81)

CHARLES E. L. WINGATE (Class of '83)

EDITOR HARVARD GRADUATES' MAGAZINE

GENERAL MANAGER BOSTON JOURNAL

INTRODUCTION BY

HON. WILLIAM T. HARRIS, PH.D., LL.D.

UNITED STATES COMMISSIONER OF EDUCATION

ILLUSTRATED

BOSTON

R. HERNDON COMPANY

1900

9°,

UNIVERSITIES AND THEIR SONS

siderably increased owing to the Civil War; nevertheless, the number of students did

not diminish to the extent that might have been expected. The number of Seniors

upon whom degrees were conferred between 1850 and 1859, averaged 82. The Class of

1860 graduated the largest up to that date; 1861, 81; 1862, 97; 1863, 120;

1864, 99; 1865, 84. President Hill's administration is memorable on two accounts; he

initiated changes in the methods of instruction with a view to convert the College into

a University, and he witnessed the final severing of the College from all interference by

the State. On April 26, 1865, the Legislature passed a bill providing for the election of

Overseers by such persons as have received from the College a degree of Bachelor of

Arts, OF Master of Arts, or any honorary degree." The voting was fixed between the

hours of ten A. M,. and

four P. M. at Cambridge,

Commencement Day;

no member of the Cor-

poration, or officer of

government and instruc-

tion was eligible as an

Overseer, or was entitled

to vote; and Bachelors of

Arts were not allowed to

vote until the fifth Com-

mencement after their

graduation. The Board

of Overseers, as thus conf

stituted, consists of the

President and Treasurer

ex officio, and of thirty

members, divided into six

classes of five members

each, every class serving

six years. In case of a

vacancy, the remaining

Overseers can supply it

by vote, the person thus

elected being "deemed to

be a member of and to go

out of office with the class

to which his predecessor

belongs." Among the

other noteworthy events

of President Hill's term

were the building of Grays

Hall (1863), and the in-

troduction of a series of

University Lectures (1863)

by specialists. These

courses, rather popular Tn

their nature, were open to

all members of the Uni-

versity; and to the public

JAMES WALKER.

on the payment of five

dollars. The Academic

Council, composed of the Professors and Assistant Professors in the various Faculties,

was founded with a view to suggest the subjects to be lectured upon and to recommend

lecturers.

CHAPTER V

FROM COLLEGE TO UNIVERSITY, 1865-1897

P

RESIDENT HILL resigned September 30, 1868: Charles William Eliot (Class of 1853),

at that time a member of the Board of Overseers, was chosen to succeed him, May 19,

1869. President Eliot's administration, which has now extended over twenty-eight years, has

been unquestionably the most memorable in the history of the University. Changes more

numerous and more radical have been wrought than in any previous period of the same

1.

JOSIAH QUINCY

EDWARD EVERETT

JARED SPARKS

JAMES WARKER

C. C. FELTON

FIVE HARVARD PRESIDENTS

9.2

UNIVERSITIES AND THEIR SONS

length; and they have affected most deeply not only Harvard itself, but the higher educa-

tion of the whole country. It is still too soon to pass final judgment on many of these

changes, but it is not too soon to state that they mark the transformation of the College

into a University.

Harvard men may also take pride in the thought that during this period Harvard has held

her primacy among American colleges more surely than at any other time since rival colleges

sprang up. Her experiments have been watched, her reforms have been first criticised and then

limitated, her methods have been adopted, in a way that affords the surest proof of her leader-

ship. Foremost

among the radical

changes at Har-

vard during Pres-

ident Eliot's ad-

ministration, was

the unreserved

adoption of the

Elective System,

long and stub-

bornly opposed

its privileges were

handed down from

class to class, un-

til at last they

reached the Fresh-

men. As a coro!-

lary to this, vol-

untary attendance

at College exer-

cises has been ac-

corded to under-

graduates, the ex-

periment being

tried first with

the Seniors in

1874-75. The

Law School has

been completely

reorganized its

course has been

lengthened from

two years to three,

and its instruction

has been made

methodical and

progressive. A

similar improve-

ment has been

effected in the

Medical School,

whose standard

was raised above

that of any other

in the country,

and whose course.

has been fixed at

three years, with

an extra year for

those who care to

avail themselves

of it. The Divin-

Ity School, long

FELTON

on the verge of

dissolution, has

been resuscitated,

and although it cannot yet be said to flourish, this is due to the general temper of the age in

religious matters, rather than to the inadequacy of the facilities of the School itself. After

repeated attempts the efficiency of the Scientific School has been enormously increased, until

now that School needs only adequate endowment in order to take rank with the most flourish-

ing departments of the University. The School of Veterinary Medicine, the Bussey Institution,

the Arnold Arboretum, the transference of the Peabody Museum of American Archaology and

the Museum of Comparative Zoology to the College, are landmarks in the extension of the

University in different directions during the past twenty years. More detailed information

will be given later, when we come to describe these branches separately.

Y

HISTORY AND CUSTOMS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY

93

To this period belongs also another wise reform - the abolition of compulsory attendance

at religious services. In 1869, the Faculty ceased to require those students who passed Sunday

at .home to attend Church, except as their guardians or parents desired; and it reduced the

number of services to be attended by those who remained in Cambridge, from two to one.

After much discussion and many petitions, attendance at prayers as well as at Sunday services,

was left to the choice of the student. The old system of regulations was completely recast: the

Faculty recognized that it had a more useful work to perform than to inspect the frogs and

buttons on the students' coats, or to fix the hour for going to bed. The decorum of the

undergraduates has improved in proportion as their independence has widened. Hazing has

disappeared, and

cases of serious

disorder have been

rare. Cribbing

at examination,

which a major-

ity of students

deemed venial

when studies were

prescribed, has

almost passed

away, since stud-

ies have been

elective.

In 1869, the

semi-annual exhi-

bitions, which used

to be held when a

committee of the

Overseers visited

the College, were

abandoned, since

it was found that

they no longer

served their orig-

inal purpose of

stimulating the

ambition of stu-

dents. In the fol-

lowing year the

system of confer-

ring "honors" on

students who had

passed a success-

ful special exami-

nation in some

one department

- as the Classics,

or Mathematics -

at the end of their

Sophomore or

Senior year, was

introduced. In

1872, the Aca-

demic Council was

remodelled, to

suggest candidates

for the higher

degrees, A.M.,

Ph.D. and S.D.,

and these degrees

acquired a real

THOMAS HILL

value from the fact

that they repre-

sented a specified amount of graduate work. Before 1872 any graduate of three years'

standing could secure an A.M. by the payment of five dollars. Indeed, the policy of the

University has been to abolish the old custom of conferring meaningless degrees. Even those

which are purely honorary in their nature (LL.D. and D.D.) have been bestowed more spar-

ingly. The venerable practice of conferring the degree of Doctor of Laws on the Governor for

the time being of Massachusetts - a practice which arose when that dignitary was ex officio

the President of the Board of Overseers.- was broken up in 1883, when Benjamin F. Butler

was Governor of the Commonwealth, and it is probable that the precedent will never be

revived.

94

UNIVERSITIES AND THEIR SONS

The salaries of the teachers were raised in 1869 - that of Professors being fixed at $4000,

that of Assistant Professors at $2500, and that of instructors at $1000; but these figures repre-

sent the maximum, and not the average sums received in the respective grades. In 1890 the

salaries of fifteen Professors and of the Librarian were raised from $4000 to $4500; those of

four law Professors from $4500 to $5000; Assistant Professors, during their second five years'

service, were to receive $3000 instead of $2500, and some of the instructors had a slight

increase, Nevertheless, the smallness of University teachers' stipends, when compared with

HARVARD GATE

the income which successful doctors, lawyers and clergymen receive for intellectual work of

relatively the same quality, indicates that public sentiment still holds educators dangerousty

cheap. Fine dormitories, spacious halls, vast museums and costly apparatus do not make a

University; men, and only men of strong intellect, of wisdom and spirituality, can make a

University and they can be secured only by paying them an adequate compensation. Until

society recognizes that the ideal educator is really beyond all price, it will go on suffering from:

evils and losses which a proper education might prevent. To lighten the work of the Harvard

Professors, the Corporation have granted them a leave of absence for one year out of every

seven. Further, a subscription has recently been opened to a fund to provide a pension

those Professors who, after a long service, are incapacitated from either age or feebleness. In

1872 the experiment of conducting "University Lectures" was found to be unsuccessful; but it

was still maintained with good results in the Law School till 1874. Summer courses in Chemis-

try and Botany were offered to teachers and other students (1874), and they constantly grew in

usefulness, SO that similar courses in other departments have been added, and now the Summer

HISTORY AND CUSTOMS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY

95

School is attended by over 600 students. In 1875, spring examinations for the University were

held in Cincinnati, and this scheme, too, proved SO beneficial that it has been extended to many

other distant cities, and to some of the preparatory schools. In 1897, examinations for admis-

sion to the Freshman Class were held in twenty-eight places outside of Cambridge, including

Denver, San Francisco, Tokyo and Bonn. In 1875, also Evening Readings, open alike to the

public and students, were introduced and they were repeated from year to year. Latterly,

more formal lectures, College Conferences, etc., have increased to such a number that there is

GRAYS HALL

rarely an evening when two or three are not in progress. Since 1883 the Boston Symphony

Orchestra has given each winter a series of concerts in Sanders Theatre, SO that the best music

is within reach of the students.

The method of instruction is -now by lectures and not by recitations in all those courses

where lectures can be given to greater advantage. The. marking system- - a survival from

the old seminary days, when marks were sent home regularly every quarter-has :been over-

hauled- and reduced to the least obnoxious condition. Formerly, the maximum mark for

any recitation was eight; the students were ranked for the year on a scale of 100, but,

though the scale was the same, no two instructors agreed in their use of it. Some were

"hard" and some were "soft" markers; some frankly admitted that it was impossible

to get within five or ten per cent. of absolute exactness; others were SO delicately con-

stituted that they could distinguish between fractions of one per cent. One instructor was

popularly supposed to possess a marking "machine; another sometimes assigned marks

less than zero. These anomalies were long recognized before a simple and more rational

96

UNIVERSITIES AND THEIR SONS

"scheme was adopted, in 1886. "In each of their courses students are now divided into five

groups, called A, B, C, D and E; E being composed of those who have not passed. To gradu-

ate, a student must have passed in all his courses, and have stood above the group D in at least

one-fourth of his College work; and for the various grades of the degree, honors, honorable

mention, etc., similar regulations are made in terms of A, B, C, etc., instead of in per cents. as

formerly." 1 The increase in the number of instructors in the various departments has also

brought about what was first proposed in President Kirkland's time - the autonomy of each

department over its own affairs, subject, of course, to the approval of the Governing Boards.

COLLEGE YARD AND HOLWORTHY HALL

Examinations are now held twice a year, at the end of January and in June, lasting about

twenty days at each period. The examinations, except in courses involving laboratory work,

are nearly all written, of three hours' length each. President Eliot, then Tutor in Mathematics,

was the first to introduce written examinations, in the course under his charge, in 1854-55-

Before that tests were oral. The College calendar was reformed in 1869, previous to which

date a long vacation had been assigned to the winter months, chiefly for the benefit of poor

students who partly supported themselves by teaching school for a winter term. As re-

arranged, the College year extends from the last Thursday in September to the last Wednesday

in June, with ten days' recess at Christmas and a week at the beginning of April.

The remarkable expansion of the University since 1869 - to which expansion these changes

bear witness - has been as great in material and financial concerns, as in policy. In 1869, the

1 W. C. Lane in the Third Report (1887) of the Class of 1881.

HISTORY AND CUSTOMS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY

97

resources of Harvard amounted to $2,257,989.80, and the income to $270,404.63 in 1896, the

capital was $8,526,813.67, the income was $1,212,201.15; and the Cambridge assessors valued

the untaxed property of the College in Cambridge at $9,216,964.59. Seven large dormitories

have been erected, viz. : - Thayer Hall, the gift of Nathaniel Thayer, in 1870; Holyoke, erected

by the Corporation, in 1871; Matthews Hall, the gift of Nathan Matthews, and Weld Hall, the

gift of William F. Weld, in 1872; Hastings Hall, the gift of Walter Hastings, in 1889; Perkins

Hall, from the bequest of Mrs. Catharine P. Perkins, in 1893-94; and Conant Hall, from the

bequest of Edwin Conant, in 1893-94. An addition to the Library, by which its capacity was

COLLEGE YARD FROM MATTHEWS HALL

more than doubled, was completed in 1877, and in 1895 a new book-stack and large reading-

room were constructed by a remodelling of the interior of Gore Hall. Austin Hall, the new

Law School, was built from plans by H. H. Richardson in 1883; the same architect designed

Sever Hall (lecture and recitation rooms) in 1880. In 1871 a mansard roof was added. to

Boylston Hall, the Chemical Laboratory, which has received several subsequent improvements;

and College House was enlarged during the same year, when also the lecture-room and labora-

tory of the Botanic Garden were completed. The Jefferson Physical Laboratory (for which

Thomas Jefferson Coolidge was the chief contributor) was finished in 1883; that year the new

Medical School in Boston was first occupied. The Museum of Comparative Zoology has grown

by successive additions, the cost of which has been largely defrayed by Alexander Agassiz, until

it now (1897) covers the two sides of the quadrangle originally proposed by Louis Agassiz; and

on the third side the Peabody Museum of Archaology, begun in 1876 and added to in 1889, has

almost reached the point of junction. The Bussey Institution (1870). the School of Veterinary

Medicine (1883), the Library of the Divinity School (1887) and the Fogg Art Museum (1894)

VOL. I.-7

98

UNIVERSITIES AND THEIR SONS

are further monuments of President Eliot's administration. For athletic purposes several build-

ings have been erected during this period: the University Boat House (1870) ; the Hemenway

Gymnasium (1879), enlarged in 1896; the Weld Boat House (1890) ; the Carey Athletic

Building (1890) the Locker Building on Soldier's Field, 1894. Two of the entrances to the

College Yard have been provided with substantial gates, one given by Samuel Johnston (1890)

and the other by George von L. Meyer (1892). The Foxcroft House was bought in 1888. The

occupancy of the old Medical School by the Dental School, has involved building changes; as

has the expansion of the Observatory, the Arnold Arboretum and the Veterinary School. The

COLLEGE YARD FROM STOUGHTON HALL

establishment of an astronomical station at Arequipa, Peru (1891), should also be included in

this list of recent increase in University buildings.

One other edifice, lemorial Hall deserves a more extended notice. In May 1865, a

large number of graduates held a meeting in Boston to discuss plans for erecting a memorial to

those alumni and students of Harvard who lost their lives in behalf of the Union during the Civil

War. A Committee of eleven were appointed, consisting of Charles G. Loring, R. W. Emerson,

S. G. Ward, Samuel Eliot, Martin Brimmer, H. H. Coolidge, R. W. Hooper, C. E. Norton,

T. G. Bradford, H. B. Rogers and James Walker. At another meeting, in July, they presented

a report, in which was the following resolution: "Resolved, That in the opinion of the graduates

of Harvard College, a Memorial Hall' constructed in such manner as to indicate in its external

and internal arrangements the purpose for which it is chiefly designed ; in which statues, busts,

HISTORY AND CUSTOMS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY

99

portraits, medallions and mural tablets, or other appropriate memorials may be placed, commemo-

rative of the graduates and students of the College who have fallen, and of those who have served

in the army and navy during the recent Rebellion, in conjunction with those of the past bene-

factors and distinguished sons of Harvard now in her keeping, - and with those of her sons who

shall hereafter prove themselves worthy of the like honor, - will be the most appropriate, en-

during and acceptable commemoration of their heroism and self-sacrifice; and that the construc-

tion of such a hall in a manner to render it a suitable theatre or auditorium for the literary

festivals of the College or of its filial institutions will add greatly to the beauty, dignity and effect

of such memorials and tend to preserve them unimpaired, and with constantly increasing associ-

ation of interest to future years." At Commencement this resolution was brought before the

SEVER HALL

alumni. After considerable discussion, in which some speakers proposed that a simple monu-

ment or obelisk would be more appropriate than a building, the matter was referred to a Com-

mittee of Fifty, which, on September 23d, reported in favor of a memorial hall. Messrs. Ware &

Van Brunt, architects, were requested to submit plans, which were formally adopted at the

following Commencement. It was also voted that the biographies of the Harvard men who

served in the war be printed. Subscriptions were immediately solicited and the College con-

veyed the land known as the Delta for the site of the new edifice. The corner-stone was laid

October 6, 1870, with a prayer by the Rev. Phillips Brooks, addresses by the Hon. J. G. Palfrey,

the Hon. William Gray, the Hon. E. R. Hoar, a hymn by Dr. O. W. Holmes, and a benediction

by the Rev. Thomas Hill. The dedication ceremonies took place July 23, 1874. The total sum

raised was $305,887.54 Sanders Theatre, to whose erection was devoted the accumulations

100

UNIVERSITIES AND THEIR SONS

from bequest by Charles Sanders (of the Class of 1802), was completed in 1876, in time to be

used for the Commencement exercises of that year. The portraits and busts belonging to the

College were placed in Memorial Hall, which has since been used by the Dining Association.

I

MEMORIAL HALL

The response given by Harvard men to the calls of patriotism and duty during the Civil

War can best be illustrated by a simple table in which the number of graduates who enlisted

is given in the first column and the number of those who lost their lives in the second :

College

626

95

Medical School

382

15

Law School

163

19

Scientific School

34

6

Divinity School

25

2

Astronomical Observatory

2

I

1232

138

As in 1861 there were 4100 and in 1866 about 5000 alumni living, it will be seen that more

than twenty-five per cent. supported the maintenance of the Union, in the field. But this per-

centage would be increased if it were possible to know exactly the number of non-graduates

who likewise enlisted. Many of these soldiers of Harvard attained distinction; but it is possible

HISTORY AND CUSTOMS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY

IOI

to mention here only Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, who died leading the charge of his colored