From collection Creating Acadia National Park: The George B. Dorr Research Archive of Ronald H. Epp

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

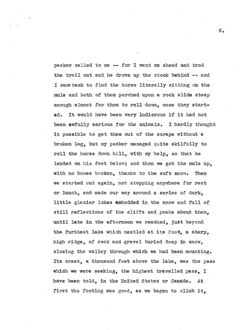

Page 9

Page 10

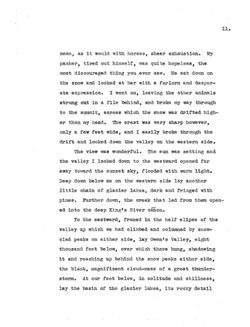

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

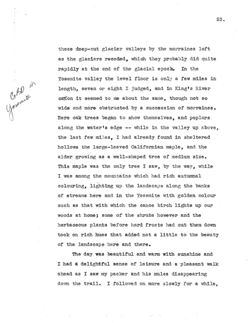

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

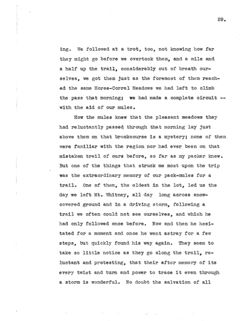

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

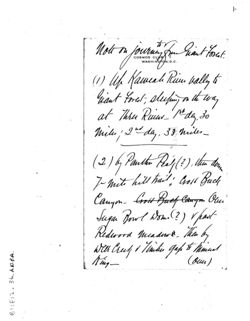

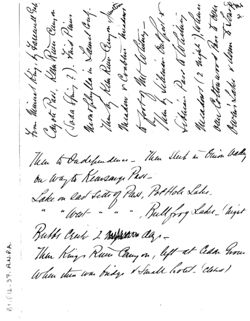

Page 61

Page 62

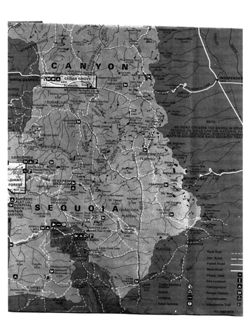

Page 63

Page 64

Page 65

Page 66

Page 67

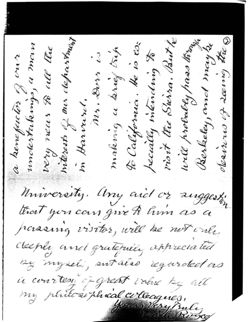

Page 68

Page 69

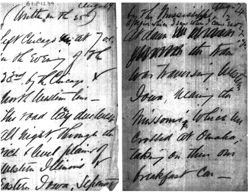

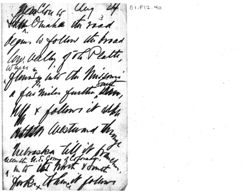

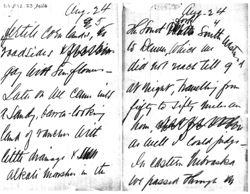

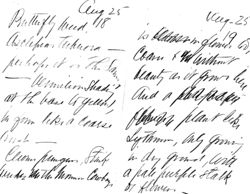

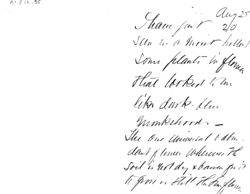

Page 70

Page 71

Page 72

Page 73

Page 74

Page 75

Page 76

Page 77

Page 78

Page 79

Page 80

Page 81

Page 82

Page 83

Page 84

Page 85

Page 86

Page 87

Page 88

Page 89

Page 90

Page 91

Page 92

Page 93

Page 94

Page 95

Page 96

Page 97

Page 98

Page 99

Page 100

Page 101

Page 102

Page 103

Page 104

Search

results in pages

Metadata

[Series III] Travel-Boston to San Francisco 1904-Siera Nevada Circuit & Mt Whitney Ascent

1904.

Sierra Nevada Circuit 7 Mt. Whitney

AS cent

Page1 of 4

[A TRIP THROUGH THE CALIFORNIA SIERRAS

IN SEPTEMBER 1904] PART 1.

I had a very interesting trip out west, from first to last,

for I had never been in any part of California before and even the

things that disappointed me interested me as well. I went straight

out to San Francisco, stayed there for three or four days, seeing

some of the Berkeley college men to whom I had letters, and then down

to Monterey, to 369 its cypresses. From there I went on down the

coast to Santa Barbara and Los Angeles. At Los Angeles I ran

down

for a day and night to Sar.ta datalina Island and then I went straight

up through the San Josquin Valley to Visalia in the Keweah River

country whence I want up by stage to Giant Porest in the national

Sequoia Park where I outfitted for my mountain trip.

: BOOK a packer, a Maine man originally and of my am name,

and some mules and we went out together for a three weeks' trip

across the stuch Sierras to Owen's Valley on their eastern side, go-

ing out through the Kern Rivor country and returning by Kearsarga

Pans and King's River, then back to Giant Forest where I started from.

Some of the men I not at Berkeley dollage, who had been out on

geological and botanical expeditions through that region laid this

route out for me as the most interesting I could follow and it cer-

tainly opened up magnificent ncenary and showed me the Sierra forests

in a most interesting way. But the distances were great, the trail

steep and difficult, the canons we had to cross profound, and the

weather was stormy. in opite of John Muir who writes of delightful

Indian summer weather lasting on until November in the mountains

there. The first storm broke while my packer and I were climbing

Me Whitney, the highest Mountain in the states. and when we reached

the tay with 04 has Present (1) wind and bitter,

sleet and SHOW I ever ran up against. We had slopt the night before,

2

as we usually did throughout the trip, without a tent although T

had carried one of light oil-silk along and when we got back to

camp our camping outfit, spread out over the ground, was already

buried two or three inches deep in snow. We got the tent up for

shelter, with some difficulty, and then my packer, exhausted by the

cold and climb gave out, the middle of the afternoon, rolled himself

up shivering in his blankets and under mine which I piled up over him

until night, and slept until I called him in the morning. We were

then camped on the edge of a high Alpine meadow, eleven thousand feet

above the sea. It snowed all that day. The next day it snowed

again but we got off in the morning and rode all day through the

storm, fearing to get snowed in upon the heights and having no feed

for our stock who depend on grazing in the mountain meadows. 'Toward

dusk we lost our way, my packer never having been over the trail

which we were following before, and we camped at sun-down on the edge

of another meadow only a thousand feet or 80 lower than the one which

we had left. By that time it had stopped snowing and we spread

out our blankets and provisions and cooked our supper only to have

it begin to snow again while we ate it. We put up the tent again

and made ourselves fairly comfortable under it although it snowed

all

through

the night. In the morning it cleared but it was bitterly

cold and all the wood about had soaked up so much moisture from the

snow that we found it impossible to start a fire. Toward noon, how-

ever, the sun came out and then the scene was beautiful beyond words,

the mountains all about us covered with fresh fallen snow which

covered too the meadow down below us and loaded down the pines and

firs that shut it in.

The next morning we started out again, found our trail and

followed it up over a high pass that led from the western to the

eastern

watershed. The snow lay three and four feet deep over the

3

summit of the pass, obliterating the trail. The last few hundred

feet of climb or either side went steeply up and down a granite slide,

the rocks big and loosely piled together and the whole hedded deep

in snow.

It was very difficult getting un it with our loaded mules

but when it came to getting them down on the other side it seemed

to me almost impossible without some accident.

However, I went

first, feeling the way as best I could among the rocks and leading

my unloaded saddle horse, a sure-footed beast, behind me. Then

when I had explored the way my packer drove the loaded animals down

along it and somehow they got through all right

no eastern

horses could have done it.

Then it was plain sailing until we reached the edge of Owen's

Valley where we came out on one of the most magnificent scenes that

I

have

ever looked on. Owen's Valley skirts the base of the high

Sierras from Nevada southward on the eastern side. Owen's River

runs down it, from the eastern slope of the Sierras further north,

to Owen's Lake which lies across the valley like the Dead Sea across

the Valley of the Jordan, a great salt pool with smooth salt plains

that were its bottom once stretching out from it to north and south.

The trail that I was following led me suddenly out above the

valley opposite this lake which lay six thousand feet below me, its

nearer surface pale gray-green, its farther surface lost in the dark

shadow and the swirling mists of a thunder squall which lay over

it, black and lawful, its cloud-mass rent by flashes of lightning,

the whole far down below the point on which we stood. Further up,

the valley lay in sunshine, a desert bounded on its eastern side by

desert mountains with here and there a splash of green upon its floor

where irrigation turned it into garden. A little later we,

too,

were swallowed up in a fierce hail storm and then descended rapidly

to the valley and rode for hours across it until long after dark, to

4

reach a village that had seemed quite near when we stood and looked

at from up above.

We slept that night at the foot of a great stack of hay, alfafa

hay, not nearly so good to sleep on as eastern Timothy, by the way,

and ate ripe grapes from off their vines and thawed out in the sun-

shine. Then we rode up the valley twenty miles to another ranch

above and the next day started up Kearsarge Pass to return back

west.

[GB.DOER]

Page I of 14.

A Trip Through The California Sierras

In September 1904. Part 2]

I started out for my mountain trip from Visalia, one of the

small agricultural cities in the broad San Joaquin valley; I went

by stage, my way lying at first across the flat plain of the valley

floor through yellow stubble fields and past immense orchards of

plun-trees whose fruit was being gathered up and dried for prunes,

then I came into the foothills region with its great orchards of

apples, oranges and lemons and its brown hill-slopes; and early in

the afternoon I reached the ranch of a man named Redstone on the

Kaweah river where I was to spana the night,

p.35

My only fellow-passenger on the stage was a young electrician

Redstore

from Ohio who had been superintending the construction of a power

plant in the high Sierra which was to supply the valley region oppo-

site

with

light and power. He had been out there all summer, and

his wife, an Ohio girl they were only married in the spring

had been there with him and was waiting for him then with horse and

buggy at a station on the stage route. But stopping at another

station an hour or two before we got there, they told him he was

wanted at the telephone and in a few moments he came back and said

that they had rung him up from San Francisco to order him to take

the next stage back and the night train on to there. He had been

away a fortnight and up travelling nearly the whole night before

and had counted on getting at least a day or two of rest and with

his wife. But he was only able to drive on with me until he reached

the station where she was to most him and then turn back. for another

five hours' ride across the dusty plain and & night upon the care.

2

His wife was waiting when he got there and her delight at getting

him back and dismay a moment afterward when he told her he had got

to leave her again in half an hour

she was all alone there with

nim so far as friends went

was quite pathetic.

Early the next morning I left the Redstone ranch and drove up

all day into the mountains over a road which climbed six thousand

feet and which brought me to a park established by the government in

one of its forest reservations for the preservation of a splendid

Gimet

growth of giant sequoias. There in the midet of a forest of these

Farest

trees, mingled with pines and firs, a trough summer camp had been

established by two ranchers from below, Broder and Hopper by name,

who also outfitted people for trips through the mountains beyond.

We passed no house upon the way after our first couple of hours

upon the road and ate our lunch by a spring at the roadside, taking

the same horses through with us all day. IC was fairly late in

the

afternoon when we reached the coniferous forest, these conifern not

growing in that region lower than five thousand feet or so above the

sea, and then in the course of another hour or two, after passing

two or three camps of negro soldiers stationed there to guard the

park and save it from fire, we reached the camp where I was going.

It had one wooden cabin which served as dining-room and kitchen,

and

a number of tents to sleep in. In the evening there was a camp-

fire which lighted up in a wonderful way the great trunks of the

seguoias and the tall, branchless shafts of the firs amongst which

they were growing.

The great sequoias have but a narrow range of altitude, growing

in fairly level belts along the western slope of the Sierras at a

height of six or seven thousand feet above the sea, where the first

heavy rain-clouds form. Nor do they follow the deeper valleys east-

ward into the mountain range but stay scattered here and there along

3

its western headlands.

Up and down the length of the Sierras they range, in widely

separated groups, for two hundred and fifty to three hundred miles.

The forest I was in, the largest of these groups, lay toward the

centre of this range; it was about eight miles in length, terminating

at either end with singular abruptness though the pines and firs

which grew along with the sequoias in it continued on uninterruptedly.

Doubtless the lower limit of the sequoia's growth is set by

rain, its growth beginning at the lowest point at which it can obtain

from the up-driven ocean air rain and dew sufficient for its needs

and a leaf-evaporation checked at night by falling temperature; while

its upward limit, lying close upon the downward one, is similarly

set by its avoidance of the mountain cold of the region to which it

has been driven by its need of moisture but which is perhaps less

natural to it than a lower one. Probably too the narrow, island-

like areas in which it grows amongst the general forest are not as

accidental as they seem but have an unseen cause in warmth-and-

moisture-bearing currents of the atmosphere or cold ones from the

mountain peaks to north and east. The largest and the finest

trees

were apt I found to grow in dells or hollows on the mountain slopes

where there was greater moisture in the soil.

The only other still existing species of sequoia, the Redwood

of commerce, grows in similar fashion in northern California along

a narrow belt between the Coast Range mountains and the sea where

the rain-fall is the heaviest in the state and where its rainless

summers are compensated by dense continual fogs. The redwood has

developed a vigorous power of sprouting from the root when the trunk

has been destroyed by axe or fire and this seems to have weakened,

through long absence of selection, the vitality of its seed but the

giant sequoia in the Sierras seemed to seed itself, so far as I could

4

see, freely wherever it could get a moist and open seed-bed.

Once I saw a small and grassy meadow hordered by some old sequoias

where a dense growth of young ones, bunched together where the seeds

had fallen, was growing up in the most vigorous way, its trees rang-

ing from young seedlings up to others of fifty feet or more in height

still clothed to the ground with their dense foliage. So probably

the reason why one does not see more young trees growing in the present

groves is mainly due to the dry climate of today in California, mak-

ing the forest floor even where the old sequoias grow too dry to serve

thein well as nursery beds; and partly too to the way in which the

sequoia forest is invaded by other trees which grow from a drier seed

bed or in deeper shade than the sequoia can. But there

can

be

no

question but that if moist and open seed-beds were prepared for it

and sown with the collected seed

a

small

expense

a new sequoia

forest would spring up far greater in extent than the existing one,

along its general range. And the tree is so beautiful in its youth

and grows SO rapidly that this would be well worth the doing, espec-

ially as the region where it might be done is one of immense future

importance to California in relief from the summer's heat and drought

in the great plains below.

The foliage of the sequoia is dense when the tree is young,

clothing it to the ground and giving it a cone-like and aspiring

form. This form it keeps, with thinner foliage, as an older tree

until the growing distance between its leading shoots and the roots

from which the sap is pumped to them begins to limit their supply,

when the lateral branches, better nourished, broaden out and give

the tree in age a round-topped character, some of these branches grow-

ing then to a great size. While this is going on the lower branches

gradually die away, leaving the great shaft of the trunk bare for

a hundred feet or more. The foliage is tassel-like in character,

5

the tassel upward turned and cone-like like the tree itself in shape,

the leaves, a warm and yellow green in color, growing stiffly for-

ward from the branchlet-stem which is itself as green as they, and

having the size and somewhat of the rounded form of bits of twine.

The roots are fibrous, not extending far away but filling the ground

around the tree with an inverted-cup-shaped mass, while the trunk

swells out near the ground to a diameter that is sometimes half again

as great as what it has fifteen or twenty feet above, buttressing

the shaft, which stands erect through the Sierra gales rather by

its own solidity and basal breadth than by a grip upon the ground

like that of oaks or pines. The largest tree I saw was two hundred

and seventy five feet high and somewhat over thirty feet across upon

the ground, its age supposed to be not less than five thousand years

and possibly considerably more, judging by the counted rings on others

that have been felled or cut into. The rings in all of the outer

portion of the older trees are extraordinarily close together, show-

ing how slow the growth to that great size has been; I could hardly

have counted some that I looked at myself without a microscope.

One's first impression of the older trees is that of giant shafts

with gnarled, irregular branches and tufts of foliage at their top:

the leaves and branches seem but an accessory to the shaft rather

than it a column built up for their support. The uppermost branches

too heighten this effect in which one feels at first a lack of grace,

standing out broken, bare and dead against the sky in nearly all the

older trees, which have been either struck by lightning in the course

of their long centuries of life or broken by some winter gale when

laden with ice and snow. But the color of the warm green foliage

high up against the sky and the warm red color of the deeply furrowed

bark below are singularly beautiful and the massive dignity of the

6

shaft itself united to the sense one has of its great age and per-

manence is most impressive, the impression growing on one rather

than lessening as one lingers in its presence. The bark is very

thick, fifteen or eighteen inches often in the older trees, and it

is said to be very resistant to fire, protecting the tree, together

with the tree's own height, and saving it when all the other forest

trees about are swept away.

The most striking tree which grows with the sequoias, companion

to it in its forests but ranging besides the whole length of the

Sierra in its lower forest helt, is the Sugar Pine, Pinus Lambertiana,

the largest of all pine trees in the world. I saw many trees in the

course of my trip that were from seven to eight feet through, a yard

above the ground, and a few that were still larger. The tree

grows

also to great height, trees of two hundred and fifty feet and upward

being often cut by the lumbermen, they told me. Its foliage is

like the foliage of our white pine, which its wood resembles also,

it being far the most valuable commercially of all the trees that

grow on the Pacific slope. It is much more open in its habit,

however, than our white pine, not making such dense masses of foliage

but thrusting out long limbs that are bare and branchless near the

tree, droop at a distance from it, and then rise again as they divide

and clothe themselves with foliage in their outer part. And these

long limbs, reaching out distinct and separate above the general

forest and waving with wide sweeps in every wind, combine with the

tree's great height and straight, majestic trunk to give it its dis-

tinctive character and the forest where it grows one of its most

striking features. The bark is finely ribbed and firm even on the

oldest trees and warm brown in color, the trunk being branchless

usually to a great height and never, so far as I had opportunity to

see, remaining clothed to the ground as it comes to be an older tree,

7

as our white pine does when growing in the open.

The forest is an open one throughout the whole Sierra region.

Deciduous trees there are none but bush-like willows, poplars and

alder trees of no great size along the banks of streams, and in the

lower valley-bottoms only, oaks and large-leaved maples. But bushes

of the sort one finds in semi-arid regions, low, still and spread-

ing, grow over the open slopes and in broad patches here and there

among the pines where sunlight falls. But there are other slopes

whole mountain sides sometimes

open or dotted only with occasional

pines, that but for them seem absolutely bare of plant or shrub,

steep slopes of rock and sand.

There are few herbaceous plants beneath the forest trees and

almost none that grow upon the open slopes

except where water

flows; the soil

granitic sands and gravels

is too barren and

the rainfall in the summer time too slight for that.

And though

there are many open meadows in among the higher mountains, left by

glaciers, they are apt to be too wet for any but marsh plants to grow

in them.

The real Sierra gardens lie along the banks of streams

alone, or here and there in patches upon slopes kept moist by water

soaking down from springs above. Or else on ledges, narrow shelters

along the faces of the cliffs, onto which water comes dripping down

in early summer from melting snow above.

When I was there it was

too late for any but a few belated flowers

gentians in the meadows

here and there; brilliant pentstemons glowing along the well-drained

sides of some steep water-course, with an occasional belated colum-

bine or other mountain flower among the rocks; but it was evident

that in spite of countless little mountain gardens brilliant in the

early summer yet the region as a whole is barren in herbaceous life

though what it has is brilliant in its flowering time and grows

abundantly where it can grow at all, in tiny losses along great barren

8

Animal life I hardly saw on all my trip, save deer in the Govern-

ment Park from which I started. The foot-prints of wild-cats were

fairly common on the snow or running along the sandy trails, and

there were occasional tracks of hares and foxes. But almost the

only animals I actually saw, the deer apart, were squirrels which

were wonderfully abundant and active everywhere, gathering un the

forest cones and storing them for winter. Birds were also rare,

though woodpeckers were fairly common; I never saw an eagle on my

trin and rarely a hawk, but owls I often heard at night, hooting in

the forest.

The men to whose camp I had come at Giant Forest had no packer

there to send out with me nor a full supply of mules and horses but

they sent me over with the camp cook a lank,

red-bearded

man

to another place, two days' ride away across the mountains, where

they had some men and animals at work [packing cement up for a reser-

voir-dam that an electric power company was building. This was a

place called Mineral King, a rough camp of a few scattered shanties

and a store, occupied in summer only a place to which miners and

prospectors came to get supplies or hunters as a starting point from

which to go up through the higher mountains and the wild region tc

the eastward. It lay at the head of one of the valleys that pene-

trated these mountains from the west; a rough stage road ran un the

valley to it, and from it several trails led up across the mountains.

My own camp out-fit included a light tent; a couple of old

comforters

comfits as they call them there

cotton wadded;

a sleeping bag which I had made myself in San Francisco out of an

army blanket and a swan's down quilt; a camera out-fit which I found

it difficult to make use of upon a trip so rough and hasty; a few

books about the trees and mountains; and a change of boots and cloth-

ing. It could be loaded easily enough upon a single mile so far as

9

weight went but the eare we had to take to shelter my cameras and their

belongings from the rough mule-hitches necessary to keep the loads from

shifting made the load a difficult one to pack.

The rest of our out-fit consisted of our food supplies, cooking uten-

sils, my packer's bed --- a pile of cotton-wadded comfits and a small

canvas bag in which he kept his clothes. This might easily have been

made a fairly light load for another mule but my outfitter, to whom I

left the detail of supplies, made it heavy with canned foods, preserves

and other needless things. We were well started on our way to Mineral

King however before I found this out.

Our way lay up through the belt

of sugar pines and giant sequoias, then along a harren ridge of rock and

A1

steeply down a vast slope of dust-like sand with desert vegetation grow-

ing sparsely through it, then across the river at its bottom three

thousand feet or so below the upland meadow where we had stopped at noon

to feed our stock and lunch

and up a similar steep slope, not quite

so high, upon its other side.

My horse, a small one at best, I found in

no condition to carry me up or down these slopes without distress, so I

got off and walked, leading him, while my long-legged guide, the cook,

guide by courtesy, for I found he knew the trail no better than I did my-

self

-- rode ahead contentedly on a lean gray horse of tougher make than

mine

which he was mounted on. The last ascent, coming toward the end

of

a long day and that the first one out, was very fatiguing; I led my horse,

moreover, and he instead of being grateful to me for walking had a most

exasperating trick of stopping every little while, pulling me back when

the climb was steepest.

At length we got up to the ton of the steeper slope, however, and

passed in solemn twilight into a gently sloping glade shadowed by giant

firs.

Some larger wild animal

we could not distinguish what

---

bounded

across it as we rode in.

Aw we went on the darkness deepened quickly

and by the time we reached the further end of the glade and rode on out

10

of it through a low, dense wood to the crest of the ridge we had

been climbing, our miles and horses only saw the trail.

Then descending again, after a little we came suddenly out of

the wood and found ourselves at the head of a grassy opening fringed

with tall, dark firs which led far and steeply down into a valley

filled with pale blue light and misty distances by the moon just

rising over the mountains opposite. It was too dark to

go

further

we had only come so far because we had passed no grazing ground before

since early in the afternoon

and we were ourselves too tired.

We stopped and listened; there was a low gurgle of water near us in

the grass, and we unpacked our mules and camped just where we were.

It was my first night out; I lay down against one of the roots

of a great fir tree a tree which I measured in the morning and

found to be eighteen feet around. It overhung the sloping meadow

at its very head, just above the little spring, so that I could hear

its water gently fall as I lay in bed. Other firs rose up on either

side the meadow, which were scarcely smaller than the one beneath

which I was sleeping and which seemed in the dimness of the night to

rise to immeasurable heights against the sky, undefined. And down

beyond lay the great depth of the moonlit, misty valley and the

pale blue, moonlit and partly shadowed mountains on its farther side.

It was a wonderful camping ground, full of poetry.

The next morning I waked with the dawn, the whole aspect of

nature changed. A few rosy clouds were floating over the mountains to th

eastward, the landscape was full of daytime color. I roused my

companion who gathered in our grazing stock; we made a hasty break-

fast and started down the trail. An hour below we reached the

meadows

Wet Meadows called

where we had planned, by the map,

to camp the night before --- a level bit of open marsh-land set

amidst a wood of pine and fir, dense for the region. We did not

11

pause there but rode on all the morning through, crossing the valley

down into which we had looked from our camping ground the night before

and climbing up its further side.

It was not until noon that we reached another camping ground,

so rocky and barren of all herbage were the valley sides which we

were traversing, but at noon we came to a most interesting spot where

a little circular meadow was enclosed by an isolated grove of giant

sequoias the first we had seen since starting

whose seedlings,

growing in dense clumps and ranging from trees just big enough to be

visible to others fifty or sixty feet in height with lower limbs

still sweeping to the ground, filled the drier fringes of the meadow.

This was the best seeding-ground of the sequoia that I saw and showed

its need quite plainly, a moist soil and an open, sheltered exposure.

We stayed there for a couple of hours

I was sorry afterward

that I had not stayed on until the next day, to make a better study

of

these younger trees. Then we rode on up a narrow valley with

a

tumiltuous stream, which we left at last to climb a huge glacier mor-

raine beyond which we passed into a hanging valley with precipitous

sides, gradually rising toward a wooded ridge which closed the valley

in behind and formed, pillared on either side by mountains, the pass

to Mineral King

Timber Gap as it was called.

our stock, evi-

dently not in good condition when we started and over-loaded for

their strength, began to show signs of exhaustion although our pace

was slow. Presently one of the mules lay down upon the trail.

A horse would not have done it until his last ounce of energy was

spent but that is one of the ways, as I found afterward, in which a

mule is different from a horse

as soon as they get discouraged

they lie down. The man I had with me, who had never packed before,

knew little more about their ways than I myself.

We

were

only

three

12

or four miles at most, as well as we could reckon from the map, from

Mineral King; a more experienced packer would have simply shifted

the pack from the mile on to one of the saddle horses and left the

mule to follow

which she could have done quite easily as her

condition in the morning showed. But I had her upon my conscience

and leaving my man to follow after me in the early morning. with the

stock, I took a few things with me for the night in case I missed

the trail

for it was then sundown and red sunset clouds were

already floating in the western sky

and went on alone, on foot,

to Mineral King.

I got up over the pass and through its timbered gap before it

got too dark to see. An open slope of dry, hard earth and broken

stone swent down from the timber's edge into the valley where the

lights of the little settlement for which I was bound could be already

seen two thousand feet below. It was rough going for I only had

a pair of stout moccasons upon my feet and the twilight was too dim

to pick one's way, but at last I got down, found the roadway in the

valley bottom, crossed a river, and made my way in the dark to Mineral

King's Post Office and only store.

It was not a very promising place to arrive at; two or three men

were lounging about a roughly carpentered room but no one seemed

prepared to shoulder any responsibility for making me at home. At

last it was arranged that I should have a room to sleep in there,

above the store, and get my meals as I could elsewhere. Then

I

asked where I could find the man who was to go out with me as packer.

A little hut one hundred feet away was pointed out and there I went

Four men were playing cards around a table; I asked if Frank Dorr

the

the man who was to go out with me as packer

was there,

and one

of the men came out to speak with me. Finding who I was he asked

me in, introduced me to his companions, one of whom then offered to

13

cook me up some supper - fried ham and fried potatoes --- cut in

chunks - soda biscuit and a pot of tea. Afterward, I sat and

talked with them awhile and then went back to my room above the store,

where I found after I had put my light out that I could see stars

from my bed through cracks and openings between the rough-hewn shingles

which made the building's roof.

The next day the man I had left behind was slow in coming on

[rrank]

sweeks

and we lost the morning but immediately after dinner Dorr and I started

on our three weeks' trip, having in the meantime overhauled our

nowh

dors

baggage and left some of the heaviest of our food supplies and other

things behind.

But as our journey was to be a hard one and Dorr, moreove

am

unit

thought

it

best

to

take

a

heavy

Dutch

oven,

on

baking-

pan and a few other heavy things along from Mineral King WO decided,

we took

along Cany

fortunately as It to take along an extra mule to earry thom.

We rode for a time up the valley we were in, passing on the way

a strongly effervescent mineral spring where we stopped and drank,

it

the water being as pleasant as that of any of the famous springs I

know.

We passed several office springs upon our trip and they seemed

to be common in the region, some of them being hot others cold,

all

and

evidently

varying

in

which

they

contained.

Their

Further un we climbed another steep morraine into a Kanging #valley,

Tracks

bare of trees, which reminded mo much of Alpino valleys I have

bace

through hist

in Switzerland just below the snow line. This valley we rode

whom

use rods,

throughout 15 length coming at its further end to a steep ascent

must

witose bare crest flanked on either side by mountains, formed the pass

to the region we were going to - a pass called Farewell Gap.

The crost was narrow its further, southern side was so steep

and shalv and the wind that blew across it so gusty and fierce that

it seemed to me for a moment my horse could hardly keep his footing

The and blew finely across gust that One

scarely

Lakes

12,874

Pwamid Peak

Colosseum Mtn.

12,777

12.473

Volcanic

Lates

Woods

Lookout Point

DIVIDE

Castle

bake

10,144

Granite Pass

Kennedy

Domes

Pass

10,673

Granite:

Lake

ME Baxter

13,125

Peak

Mt. Clarence King

12,905

able to identify sources of historic photographs or paintings of the

> Visalia landscape at the turn of the 20th-century.

>

> My interest grows out of completion of a biography of George Bucknam

> Dorr (1853-1944), the founder and first superintendent of Acadia

>

National Park. This pioneer conservationist journeyed with a guide to

> the Sierras in 1904 after receiving some expert advice from

> acquaintances at the University of California, Berkeley. He left a

> detailed 40- page typewritten naturalists narrative of his travels from

> Visalia where "I went up by stage to Giant Forest in the National

> Sequoia Park where I outfitted for my mountain trip."

>

> Their three week trip took them across the Sierras--where they made one

> of the first ascents on the new trail up Mt. Whitney-- the two men onto

> Owen's Valley on the eastern side of the Sierras "going out through the

> Kern River county and returning by Kearsage Pass and King's River, then

> back to Giant Forest where I started from." The use of historic images

> of the landscapes Mr. Dorr encountered would bolster his narrative which

> I discuss in my biography (forthcoming from the Library of American

> Landscape History/University of Massachusetts Press). I'd appreciate any

> guidance you can provide.

>

> Thank you!

>

> Ronald H. Epp, Ph.D.

> 47 Pondview Drive

> Merrimack, NH 03054

> (603) 424-6149

> eppster2@myfairpoint.net

>

Ronald H. Epp, Ph.D.

47 Pondview Drive

Merrimack, NH 03054

(603) 424-6149

eppster2@myfairpoint.net

ISLANDERbioart0605.doc

46 KB

https://web.mail.comcast.net/zimbra/h/printmessage?id=2623&tz=America/New_York&xim=1

2/2

8/30/2021

Gmail - 1904 Sierra Exploration

Gmail

Ronald Epp

1904 Sierra Exploration

1 message

Ronald Epp

Mon, Aug 30, 2021 at 12:08 PM

To: raydelea@verizon.net

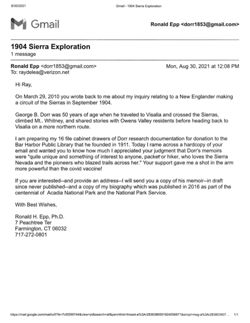

Hi Ray,

On March 29, 2010 you wrote back to me about my inquiry relating to a New Englander making

a circuit of the Sierras in September 1904.

George B. Dorr was 50 years of age when he traveled to Visalia and crossed the Sierras,

climbed Mt.. Whitney, and shared stories with Owens Valley residents before heading back to

Visalia on a more northern route.

I

am preparing my 16 file cabinet drawers of Dorr research documentation for donation to the

Bar Harbor Public Library that he founded in 1911. Today I rame across a hardcopy of your

email and wanted you to know how much I appreciated your judgment that Dorr's memoirs

were "quite unique and something of interest to anyone, packet or hiker, who loves the Sierra

Nevada and the pioneers who blazed trails across her." Your support gave me a shot in the arm

more powerful than the covid vaccine!

If you are interested--and provide an address--I will send you a copy of his memoir--in draft

since never published--and a copy of my biography which was published in 2016 as part of the

centennial of Acadia National Park and the National Park Service.

With Best Wishes,

Ronald H. Epp, Ph.D.

7 Peachtree Ter

Farmington, CT 06032

717-272-0801

https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0ik=7c5f299744&view=pt&search=all&permthid=thread-a%3Ar2836386591924056671&simpl=msg-a%3Ar283803907

1/1

8/30/2021

Raymond Delea '70 I Saint Mary's College

resources/nondiscrimination-policy)

Login (/onelogin_saml/sso?destination=raymond-delea-70)

https://www.stmarys-ca.edu/raymond-delea-70

7/7

Page 1 of 2

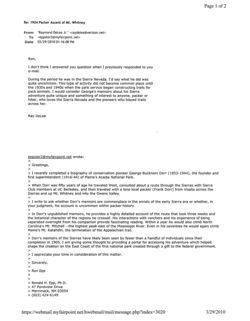

Re: 1904 Packer Ascent of Mt. Whitney

From "Raymond DeLea Jr."

> When Dorr was fifty years of age he traveled West, consulted about a route through the Sierras with Sierra

Club members at UC Berkeley, and then traveled with a lone local packer (Frank Dorr) from Visalia across the

Sierras and up Mt. Whitney and into the Owens Valley.

>

> I write to ask whether Dorr's memoirs are commonplace in the annals of the early Sierra era or whether, in

your judgment, his account is uncommon within packer history.

>

> In Dorr's unpublished memoirs, he provides a highly detailed account of the route that took three weeks and

the botanical character of the regions he crossed. His interactions with ranchers and his experience of being

separated overnight from his companion provide fascinating reading. Within a year he would also climb North

Carolina's Mt. Mitchell --the highest peak east of the Mississippi River. Even in his seventies he would again climb

Maine's Mt. Katahdin, the termination of the Appalachian trail.

>

> Dorr's memoirs of the Sierras have likely been seen by fewer than a handful of individuals since their

completion in 1905. I am giving some thought to providing a portal for accessing his adventure which helped

shape the creation on the East Coast of the first national park created through a gift to the federal government.

>

> I appreciate your time in consideration of this matter.

>

> Sincerely,

>

> Ron Epp

>

>

> Ronald H. Epp, Ph.D.

> 47 Pondview Drive

> Merrimack, NH 03054

> (603) 424-6149

https://webmail.myfairpoint.net/hwebmail/mail/message.php?index=3020

3/29/2010

8/30/2021

Raymond Delea '70 I Saint Mary's College

COVID-19 Information and Resources (https://www.stmarys-

ca.edu/covid-19-news-resources)

For Alumni (/for-alumni)

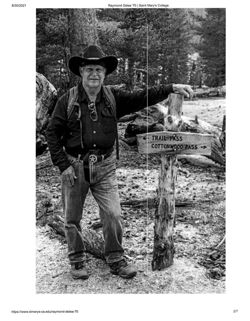

Raymond Delea '70

Submitted on Wednesday, April 1, 2020

Ray retired from Hughes Aircraft Company in 2013 after 40 years of

service as a manufacturing engineer in custom hybrid and

microwave microcircuit manufacturing. He has been married to his

wife Pattie for 47 years and resides with their daughter Daniella in

Lakewood, CA. Ray recently published his first book, "High Sierra

Adventures" chronicling his six summers working for Mt. Whitney

Pack Trains on the eastern slopes of the Sierra Nevada during the

1960s.

https://www.stmarys-ca.edu/raymond-delea-70

1/7

8/30/2021

Raymond Delea '70 I Saint Mary's College

TRAIL PASS

COTTONWOOD PASS

2/7

https://www.stmarys-ca.edu/raymond-delea-70

Viewer Controls

Toggle Page Navigator

P

Toggle Hotspots

H

Toggle Readerview

V

Toggle Search Bar

S

Toggle Viewer Info

I

Toggle Metadata

M

Zoom-In

+

Zoom-Out

-

Re-Center Document

Previous Page

←

Next Page

→

[Series III] Travel-Boston to San Francisco 1904-Siera Nevada Circuit & Mt Whitney Ascent

| Page | Type | Title | Date | Source | Other notes |

| 1-5 | Book Excerpt | A Trip Through the California Sierras in September 1904 Part 1 / George B. Dorr | 09/01/1904 | ANP (Acadia National Park) Archives, B.1.F.12.19 | - |

| 6-20 | Book Excerpt | A Trip Through the California Sierras in September 1904 Part 2 / George B. Dorr | 09/01/1904 | ANP (Acadia National Park) Archives, B.2.F.9 | Annotated by Ronald Epp: Note: Revision of Early Draft. No Finished Transcript |

| 21-60 | Letter | Letter from George Dorr to David Ogden: A Trip Through the California Sierras in September 1904 Part 3 / George B. Dorr | 11/07/1904 | ANP (Acadia National Park) Archives, B.1.F.16: Copy also in B.2.F.9.Pt.2 | Annotated by Ronald Epp |

| 61-62 | Notes | Western Trip 1904: GBD's Exploration of the Sierra Nevada Mountains | 08/01/2021 | Ronald Epp | - |

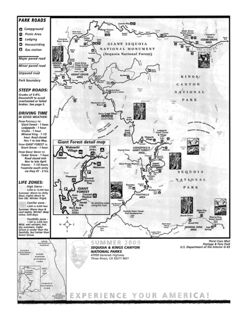

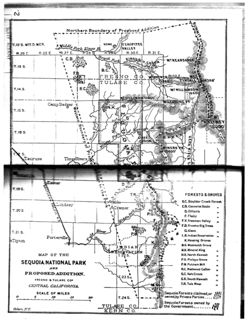

| 63 | Map | Sequoia & Kings National Parks | - | - | - |

| 64-67 | Website | Wikipedia: Benjamin Ide Wheeler | 08/28/2021 | Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benjamin_Ide_Wheeler | - |

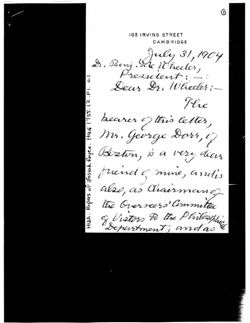

| 68-69 | Letter | Letter from Josiah Royce to Benjamin Ida Wheeler | 07/31/1904 | HUA.Papers of Josiah Royce: HGG: 1755.12.F1.C1 | - |

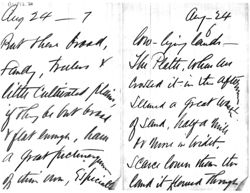

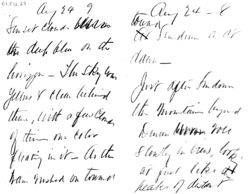

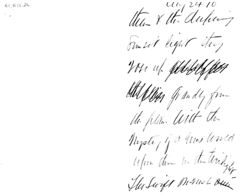

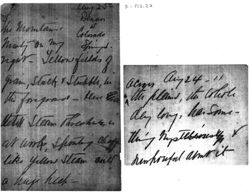

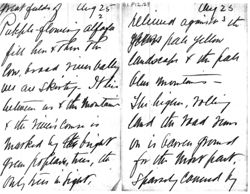

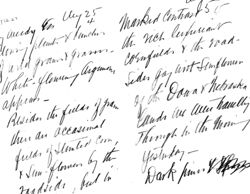

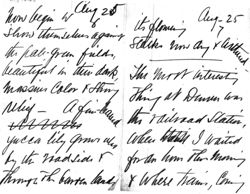

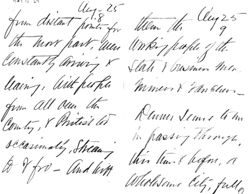

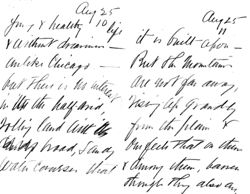

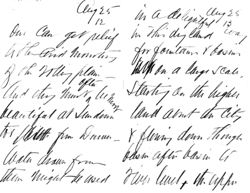

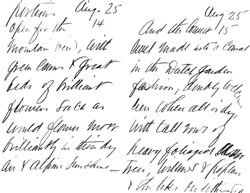

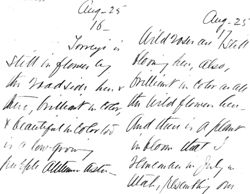

| 70-89 | Notes | George B. Dorr Handwritten Notes | 08/24/1904 | ANPA B.1.F.12 | - |

| 90-96 | Book Excerpt | At Mount Whitney | 1890 | A Summer of Travel in the High Sierra / Joseph LeConte | Annotated by Ronald Epp: Note: As an undergraduate at U.C. Berkeley, LeConte's diary-like account of his 652 mile trip in 1890 is remarkably similar to what George B. Dorr faced & documented in 1904. Could this book have played a role in Dorr's plans? |

| 97 | Email from Ronald Epp to Terry Ommen: Visalia Photographs: c. 1904 | 03/25/2010 | Ronald Epp | - | |

| 98-99 | Email from Ronald Epp to Terry Ommen: RE: Visalia Photographs: c. 1904 | 03/28/2010 | Ronald Epp | - | |

| 100-101 | Email from Ronald Epp to Ray Delea: 1904 Sierra Exploration | 08/30/2021 | Ronald Epp | - | |

| 102 | Email from Ray Delea to Ronald Epp: Re: 1904 Packer Ascent of Mt. Whitney | 03/29/2010 | Ronald Epp | - | |

| 103-104 | Website | Raymond Delea '70: Saint Mary's College | 08/30/2021 | From https://www.stmarys-ca.edu/raymond-delea-70 : original web page no longer on website | - |

Details

1904