From collection Creating Acadia National Park: The George B. Dorr Research Archive of Ronald H. Epp

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

Page 62

Page 63

Page 64

Page 65

Page 66

Page 67

Page 68

Page 69

Page 70

Page 71

Page 72

Page 73

Page 74

Page 75

Page 76

Page 77

Page 78

Page 79

Page 80

Page 81

Page 82

Page 83

Page 84

Page 85

Page 86

Page 87

Page 88

Page 89

Page 90

Page 91

Page 92

Page 93

Page 94

Page 95

Page 96

Page 97

Page 98

Page 99

Page 100

Page 101

Page 102

Page 103

Page 104

Page 105

Page 106

Page 107

Page 108

Page 109

Page 110

Page 111

Page 112

Page 113

Page 114

Page 115

Page 116

Page 117

Page 118

Page 119

Page 120

Page 121

Page 122

Page 123

Page 124

Page 125

Page 126

Page 127

Page 128

Page 129

Page 130

Page 131

Page 132

Page 133

Page 134

Page 135

Page 136

Page 137

Page 138

Page 139

Page 140

Page 141

Page 142

Page 143

Page 144

Page 145

Page 146

Page 147

Page 148

Page 149

Page 150

Page 151

Page 152

Page 153

Page 154

Page 155

Page 156

Page 157

Page 158

Page 159

Page 160

Page 161

Page 162

Page 163

Page 164

Page 165

Page 166

Page 167

Page 168

Page 169

Page 170

Page 171

Page 172

Page 173

Page 174

Page 175

Page 176

Page 177

Page 178

Page 179

Page 180

Page 181

Page 182

Page 183

Page 184

Search

results in pages

Metadata

[Series III] Travels-Boston to San Francisco 1904-Sierra Nevada History

TRAVELS Boston to San Fromisco!9a

Sierra Nevada History.

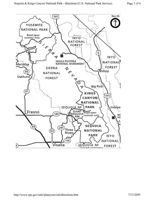

Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Park - directions (U.S. National Park Service)

Page 3 of 4

395

North

YOSEMITE

NATIONAL PARK

Road open

summer only.

INYO

s

NATIONAL

FOREST

6

INYO

DEVILS POSTPILE

NATIONAL

Mariposa

NATIONAL MONUMENT

SIERRA

FOREST

49

Bishop

NATIONAL

Oakhurst

FOREST

A

A

Big Pine

41

KINGS

395

CANYON

NATIONAL

SEQUOIA NF

PARK

Indeper

Fresno

GIANT

180

TSEQUOIA

Road open

NM

summer only.

MA

HIS

L

99

SEQUOIA

245

63

Three

NATIONAL

Rivers

PARK

INYO

198

NATIONAL

8

Visalia

SEQUOIA NF

FOREST

http://www.nps.gov/seki/planyourvisit/directions.htm

7/13/2009

Templer and Playgrounds: The Sierra (lub in the W; derners.

Anne 7. Hyde

I

1904 an enthusiastic Sierra Club member penned

The photographs and their captions, demonstrating

the following words to describe a photograph he

a clear change in attitudes toward nature in the years

had taken of Yosemite Valley while enjoying the

between 1901 and 1922, are contained in albums kept

annual Sierra Club Outing:

by California Sierra Club members to commemorate

Sunday morning, too!-and we stood at the portals of one

their Annual Outing to the mountain wilderness.

of the grandest natural cathedrals on the Pacific Slope. From

Founded in 1892 by John Muir and a group of Bay Area

the richly carved granite choir galleries came the joyous music

professionals with the purpose of "exploring, enjoying,

of many waters, and the deep organ tones of full throated

and rendering accessible the mountain regions of the

waterfalls pealed forth ever and anon as we threaded its aisles.

Pacific Coast,"3 the Sierra Club introduced the Annual

Outing in 1901. Each summer the club organized a

His photograph demonstrates the same reverence.

month-long visit to the wilderness, generally in the

Graceful pine trees frame a vision of towering granite

California Sierra. The most popular spots included

walls split by a tumbling cataract. No human presence

Yosemite and its surrounding area and the region that

dares to break the sublime spell.

now encompasses Sequoia and Kings Canyon national

Seventeen years later, two exuberant participants in

parks According to the officers of the club, "This Out-

a 1921 Outing recorded their adventures in a different

ing is intended to awaken an interest in and afford an

tone. Under a photograph of a white mule standing in

exceptional opportunity for visiting the most wonderful

a mountain snow field with legs splayed and nostrils

and picturesque High Sierra Region of California."

flared, they wrote:

In 1901, the Sierrans recognized that their first Outing

Has anybody here seen Blackie

was a unique event. The announcement to the general

He wandered off the trail

membership of the expedition to Yosemite stated,

He took our dunnage with him

We've searched without avail.

"Never before has there been presented such an oppor-

tunity for visiting so comfortably and enjoyably this

We're in the High sierra

wild, rugged, and romantic region of our High Sierra."5

We've no beds, no food.

We trusted that white Blackie

Each year, eighty to two hundred Sierrans of varying

We thought he was good.

ages, occupations, and outdoor experience set off for

Has anybody here seen Blackie

He bears a great white pack.

(Above) "After." Photograph by H.C. Stinchfield (1919).

If should come across him,

(Right) "Summit of Mount Gould 13,300 feet." Photograph

Please will you send him back.2

by J. LeConte (1901).

208

CALIFORNIA HISTORY, 101.66,*3 (1987)

This content downloaded from

137.49.125.110 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 13:48:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

the wilderness, accompanied by a platoon of Chinese

or black cooks, an army of mules, and several tons of

gear. The pattern of these trips varied little. The club

set up a main base camp, and a wide range of side

expeditions took off from there. The participants in the

outings kept voluminous journals describing every as-

pect of the event, and each year they took hundreds

of photographs which they placed in carefully cap-

tioned albums

Over the years, these albums show distinct changes

in the way the Sierrans photographed themselves and

the surrounding wilderness. The photographs fall into

three general categories: nature as awesome, a sublime

temple to approach with humility; nature being con-

C. quered; and nature conquered, a gigantic playground.

In general, these categories develop chronologically,

the first present in 1901 and fading by 1910, the second

appearing by 1907 and continuing through 1922, and

the third present only after 1915

By the late nineteenth century, the art world's search

for the sublime and the ideals of Romanticism and Tran-

scendentalism had begun to move Americans from the

contemplation of paintings of dramatic landscapes in

art galleries and drawing rooms to the observation of

real landscapes. Tourists gaped at towering mountains

and peered into awful chasms from well-appointed

Pullman cars or observation decks, but still, few Ameri-

cans had ventured into the wilderness-and certainly

not in the numbers or for the long time that the Sierra

Club proposed. Some Sierra Club members preparing

for the early Outings worried that their love of nature

would place them in the category of eccentric. Others

took pride in their eccentricity, exclaiming, "There are

those who believe that in this modern day the love of

nature-wild nature-is vanishing from the world.

Probably they read their Thoreau of a vacation on the

verandas of summer resorts; at all events, they are not

members of the Sierra Club."6 The Sierrans could look

for praise for their undertaking from President Theo-

dore Roosevelt, whose advocacy of the "strenuous life"

as an antidote to "flabbiness" and "slothful ease" en-

couraged a wide variety of vigorous outdoor recreational

activity>

Even for the Sierrans, though, life in the outdoors

was unfamiliar. Many described themselves as com-

plete "tenderfeet" and admitted their need for an initi-

ation into the ways of the wild life. One remembered,

"To get into our bags was the work of a few moments

Ann F. Hyde is a doctoral candidate in History at the

University of California, Berkeley. Her thesis is on the resort

hotels of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

210

CALIFORNIA HISTORY

This content downloaded from

137.49.125.110 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 13:48:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

and a tired mountaineer needs no sedatives. But the

extreme novelty of the situation assisted by the villain-

ous unevenness of the ground and by prowling mules,

One must have the fullest use of the lungs and the

had the effect of keeping at least one 'tenderfoot' awake

loosest corset is some impediment to the breathing As

for some time." Later that night this particular brave

ordinarily worn they are impossible."

Sierran roused the entire camp in a loud brawl with a

Outing photographs from the early years demon-

mule, unfortunately mistaken for a wild grizzly bear.

strate the tentativeness of the ties the Sierrans felt to

Another clue to the novelty of the situation appears

the natural world. Awe before what John Muir called

in the concern about proper attire for women. The an-

"a window opening into heaven, a mirror reflecting the

nouncement of the 1902 Outing advised, "Skirts can

Creator" was the dominant mood. Joseph LeConte, a

be short, no more than half way from knee to ankle,

famous geologist and experienced outdoorsman) rarely

and under them can be worn shorter, dark, colored

took pictures of people in the wilderness When he

bloomers." The writer added, "It would be unsafe to

did, the people appear out of place, not sure how to

ride other than astride on portions of the trip. and no

behave. "Dinner in Camp," for example, depicts an

side saddles can be obtained." As a helpful hint about

elegant dinner party which seems, incidentally, to have

hiking and climbing garb, and to assure critics that

taken place in the Yosemite wilderness. Several ele-

proprieties would be observed. one writer suggested,

gantly dressed men and women sit stiffly at a table

"For high climbing many ladies wear a skirt of moderate

covered with a table cloth and set with china and silver.

length until out of sight of the main camp and then

No chandelier hangs above, and a pine bough decorates

leave the skirt under a rock Women SO rarely

the table, but these are the only concessions to the

engaged in such rigorous activities that a writer for

wilderness.

Outing, an early sporting magazine, broached the del-

This discomfort evolved out of the context in which

icate subject of underwear in print. She stated ada-

the appreciation of wild nature developed Che nine-

mantly, "No one should climb mountains in corsets.

teenth-century transformation in the American view of

wilderness from an enemy to be subdued to the embod-

iment of the sublime brought with it a sense of hesita-

(Left top) "The Nine at Their Base Camp." Photograph

tion. The wilderness became a shrine where nature

by William F. Bade (1904).

lovers expected to be impressed intimidated, and

awed. "Here the appropriate mood is worship," wrote

(Left) "Mist Falls." Photograph by J. Leconte (1901).

one visitor to Yosemite. It is John Muir's exquisite in-

(Above) "King's Canyon." Photograph by L.T. Parsons

sight to the effect that the vale of the Yosemite looked

SEPTEMBER 1987

211

This content downloaded from

137.49.125.110 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 13:48:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

at from its western end is architecturally like a huge

temple lighted from above." " The notion of eating

a

meal in God's greatest cathedral must have seemed

alien to the early Sierrans. Even if they viewed the meal

as a kind of sacrament, like communion, it could not

have been a comfortable or familiar experience.)

Most of the early photographs show that nature is

in control rather than recording the Outing participants

1904

in the act of defiling the temple.William Bade took

pictures of the 1904 Outing with an emphasis on the

luminary give fair warning of his pending leave, the

awful power of nature. His album is filled with images

fair damsel Merced coyly wraps the gentle shadows

of stupendous acts of nature: trees hit by lightning,

'bout her graceful form." Although nature is less

avalanche paths, gigantic rifts in boulders, and tremen-

imposing in this guise, man does not enter the scene

dous waterfalls. Occasionally, Bade's photographs in-

unless bidden. William Bade described his conception

clude people, but they are dwarfed by the landscape

of man's relationship to nature, "We learned to interpret

"The Nine at their Base Camp the Evening before the

the various languages in which nature speaks to the

Climb Watching the Wonderful Play of Light on the

children of men. She led us step by step to the summits

Forbidding Rock Masses of Banner and Ritter" shows

of her beauties, seduced us into the secret places of her

worshippers at the base of a magnificent temple. 12 The

hiding and day by day revealed the arcana of her being.

dimly silhouetted humans crouch to stare up at the

We were acolytes in the grand temple of the eternal." 4

brilliantly lit snowy mass of Mount Ritter.

A standard photograph evolved which consciously

Typically, humans are simply absent from the early

displayed the sublimity of the wilderness. A tree is the

Outing photographs. With a few exceptions, Joseph

foreground provides perspective, and the immense

LeConte included human figures only to underscore

landscape fades into the background. Joseph LeConte

the immensity of a waterfall, a sequoia, or a boulder.

mastered this composition in "Mist Falls" and "River

Other photographs used captions to personify nature,

View." Philip Carleton adopted the same format in "Un-

occasionally making it less intimidating, After a series

icorn Peak from the Meadows," in which a huge pine

of photographs depicting the rapids and falls of the

tree looms in the foreground and the river roars directly

Merced River, one photographer included a picture of

toward the viewer. All of this provides a frame for the

the river in a calmer stage with following caption: "At

mass of Unicorn Peak. Similarly, a photograph taken

the close of day when the slanting beams of our chief

by E.T. Parsons in 1902 emphasizes the vast sweep of

212

CALIFORNIA HISTORY

This content downloaded from

137.49.125.110 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 13:48:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

little briar and brush, my face was red with sunburn,

and I once annexed eight freckles to my nose."

Kings Canyon as it stretches away from the tree in the

The physical pleasures of wilderness life gradually

foreground Such photographs echo the conventions

came to occupy more attention than spiritual lessons

of nineteenth-century paintings, in which the blasted

in the journals of Outing participants One Sierran

tree in the foreground of a landscape demonstrates

exulted in 1909, "To walk over hard snowdrifts under

the power of God's whimsy. Just as in a Bierstadt or

a hot sun, to burn at midday and shiver at night

Cole painting, in which humans rarely appear except

all without taking cold: to be a barbarian and a commu-

as foils to demonstrate the magnificent scale of nature,

nist, a homeless and roofless vagabond, limited to one

the photographs are composed to emphasize vastness

gown or suit of clothes all of these breaches of

and power, with sheer cliffs looming up from valley

convention became commonplaces in such a life as this,

floors and. canyons fading into endless ranges of

part of the adventure.** Another described the joys

mountains.

of the 1907 Outing: "The weak grew strong and the

strong invincible. Men and women made knapsack

trips, young girls tramped over a hundred miles in a

B

week, and in all the company, never a creature, even

eginning about 1907, however, the Sierrans

to the horses, was ill." These humans felt at ease in

seemed to take nature for granted, feeling

the wilderness and little concerned with the awesome

more at ease in their wild surroundings with

forces nature could unleash upon them.

each passing summer. "I laugh now when I think of

The new focus had a competitive aspect, as Sierrans

those first trips wrote one woman in 1909 > Of

grew increasingly intent on conquering the challenges

course I wore a long skirt, a shirt waist, straw hat and

of the wilderness Using their newly discovered phys-

veil, kid gloves and low shoes and was as uncomfort-

ical prowess, they tackled nature and exulted in their

able as a woman could be. My skirt caught on every

victories. A 1907 photograph depicts a group of people

standing squarely on the summit of a mountain) Both

men and women smile proudly and plant their feet

(Far left) "Unicorn Peak from the Meadows." Photograph

by Philip Carleton (1907).

firmly on the peak. The caption reads, "Conquered

Dana!-Yes, to be sure, for this constitutes the roll call

(Left) "River View." Photograph by J. Leconte (1901).

that was taken on the summit." A similar photograph

in the same album is captioned "Just holding down

(Above) "Chow Line." Photograph by E.T. or M.R. Parsons (1909).

Mount Hoffman for a while" and shows a large group

SEPTEMBER 1987

213

This content downloaded from

137.49.125.110 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 13:48:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

snow on a rocky slope. A series of photographs by

Elizabeth Crispin emphasized the rough terrain cov-

ered by the hikers, and "Coming Down Off Mount

of hikers resting contentedly on the summit, relaxed

Conness," a 1919 photograph. depicts a group inching

and smiling in their lofty and barren surroundings. A

its way down a sheer rock face. Marion Parsons de-

woman who mastered Mount Rainier commented on

scribed her experiences on a similar endeavor on South

her satisfaction, "Only a mountaineer can appreciate

Kaweah Peak, "It seemed the wildest of follies to stir

the sense of exhilaration with which we contemplated

a hair breadth from the hand or foot hold which had

the vast expanse of the crater and told ourselves that

proved firm toward the untried possibilities that the

we had conquered the kingliest among all the moun-

next step held. Slowly and with greatest care. we crept,

tains of the United States."

crawled, and clambered along the knife edge." For

Mount Rainier may have been the "kingliest," but

these climbers, the wilderness provided challenges that

Mount Whitney reigned as the highest mountain in the

simply had to be met.

continental United States, and it was a Sierra Club favo-

The new obsession with conquering nature appears

rite. A few Sierrans climbed it in the early years, but

even in photographs of the landscape. Gone are the

they never attempted it en masse or took pictures of

carefully framed images of nature's grandeur; in their

themselves on the summit In 1916. Jessie Treat wrote

place appear photographs of single peaks, precisely

proudly, "On Wednesday morning two hundred left

identified and measured. The captions provide intor-

for Crabtree Meadows base camp to ascend Mount

mation, not poetry: "On top of Mount Brewer, 13,577

Whitney the following day. One hundred seventy-five

feet," "Looking Up Bubbs Creek of Evolution Peak,"

reached the summit, the largest party of mountaineers

with peaks named and measured These photographs

ever registered there." A few years later Perry Evans

show little interest in pictorial qualities

photographed the trip up Whitney. He took ten shots

Generally the photographers of the years after 1910

of the group lolling about on the summit and ten shots

did not concern themselves with scenery but docu-

of the surrounding scenery and compiled a complete

mented instead the presence of man in nature. The

list of those who made it up in the order of their arrival

on the summit

(Above) "We Take Turns Serving." Photograph by Parsons (1912).

Many of the photographs showcased the technical

skills of the Sierrans. Marion Randal Parsons took a

(Top right) "Snowballing on the Fourth of July." Photograph

picture of club members successfully crossing a difficult

by Marion Persons (1912).

pass in 1912. "Treading down the snow" shows a single

(Right) "Treading Down the Snow." Photograph by Marion

file of hikers crossing a steep and treacherous patch of

Parsons (1912).

214

CALIFORNIA HISTORY

This content downloaded from

137.49.125.110 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 13:48:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sierrans now took pictures of their base camps and of

their daily activities, no longer disturbed by the idea

that they were defiling the sanctity of nature. Either

bered by the austere grandeur of the scene, we quietly

Marion or E.T. Parsons captured club members waiting

withdrew in detached groups and slowly pondered the

hungrily in their vast "chow line" and snapped a shot

awe-inspiring spot."

of the serving table, gaily decorated with Japanese lan-

terns and the grimy but smiling faces of garland-be-

decked Sierrans. People eating, washing, swimming,

sleeping, and groaning uphill fill the images of this era.

B

V 1909 the rhetoric of the sublime was rare

Recognizing the novelty of their adventure, the Sier-

both in print and on film. The Sierrans now

rans found their stay in the wilderness exhilarating

conquered nature's wonders instead of wor-

rather than spiritually moving. Marion Parsons's 1912

shipping them. Certainly some of the earlier ideals exist

photograph entitled "Snowballing on the Fourth of

in the photographs of waterfalls and mountain lakes,

July" illustrates some of the new qualities. No longer

but in all the albums from the second decade of the

did people feel obligated to stare off into the scenery

twentieth century these pictures are scattered among

and wonder about lessons to be learned from the inspir-

examples of the newer style of Sierra Club photography.

ing sight. Now Sierrans could ignore the awesome

In photographs taken after 1915 evidence of the sublime

views and hurl snowballs at one another, and even

aesthetic disappears almost entirely, and the later pic-

capture the disrespectful scene on film. One club mem-

tures focus nearly exclusively on the presence of hu-

ber who climbed Mount Lyell in 1914 echoed the chang-

mans in the wilderness. Though it still appeared in

ing attitude: "There was no sea in sight but everything

both written and pictorial memoirs, the need to conquer

else in geography seemed to be there: vast snowfields,

nature was losing its urgency as well. Marion Parsons

desert, lakes, wicked looking Ritter. At first, however,

remembered a 1920 crossing of Muir Pass, "We passed

we seemed less absorbed in these wonders than in the

safely with scarcely a flounder. We felt we had made

joyous chopping together in our tin cups of snow and

history that day when two hundred sixty human be-

several gallons of strawberry jam, and the subsequent

ings, one hundred animals, and eighteen thousand

consumption of this 'Sierra Sundae'!" Such a reaction

pounds of supplies crossed Muir Pass without one mis-

differed from that of a 1902 climber who wrote, "So-

hap."2" The photographs of this era frequently depict

SEPTEMBER 1987

215

This content downloaded from

137.49.125.110 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 13:48:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Sierra Club Outing photographs offer concrete

evidence of how this change took place and what it

meant to the people at its forefront. In 1901, the Sier-

rans, awed and intimidated by the wilderness, ven-

tured into it with trepidation. They hoped to learn of

the mysteries of nature and responded to its challenges

with wonder and respect. The photographic record of

and had helped popularize the concept-as Americans

these early trips captured an omniscient nature where

in general were discovering the mobility offered by the

man was but a plaything. Later, the wilderness evoked

automobile and experiencing serious reservations

a new reaction from the Sierrans. They met its chal-

about the quality of urban life and its implications for

lenges with vigorous activity rather than dumb awe.

American society. "We are not going to be happy clut-

The Outing participants conquered mountains and re-

tered together in houses backed up against each other

corded their presence in the landscape. Finally, the wil-

in cities," wrote Franklin Lane in the National Geographic

derness, now conquered, evolved into a place for

in 1920. "This is not the normal natural life for us We

people to play, and Sierra Club members noted ambiv-

are not going to have cities made up of apartments and

alence toward mass appreciation of "their" wilderness,

boarding houses and hotels and produce the good,

"The accessibility of the [Tuolumne] meadows by auto-

husky Americanism that has fought our wars and made

mobiles is an advantage or a disadvantage according

this country." His concern echoed Theodore

to one's point of view. One's first impulse is to resent

Roosevelt's suggestion that "as our civilization grows

this intrusion into Nature's heart

Upon reflection,

older and more complex we need a greater and not a

however, one can but rejoice when increasing numbers

lesser development of the fundamental frontier values"

of one's fellow men find healthful pleasure in Nature's

of physical strength, courage, and general toughness.

gifts."43 The wilderness was now perceived as a refresh-

Between the end of the nineteenth century and the end

ing escape from the activities of the business world, a

of the second decade of the twentieth, a significant

place where the Sierrans could do things they could not

portion of the American population had come to see

do on Market or Montgomery streets or on the cam-

wilderness not as a threat to be eliminated but as a

puses of Stanford or Berkeley. For its users, the wilder-

resource providing respite from and perhaps even a

ness had changed from a temple to a playground

See notes on page 236.

cure for the ills of modern society.

219

SEPTEMBER 1987

This content downloaded from

137.49.125.110 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 13:48:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

11/26/2019

The history of Three Rivers: A place of inspiration - 3R News

News and views of Three Rivers, Calif.,

Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks

Log in here

HOME

NEWS

FEATURES

EVENTS

HEALTH AND FITNESS

NATIONAL PARKS

MORE

SUBSCRIBE

SERVICES

CONTACT US

The history of Three Rivers: A place of

inspiration

7 MONTHS AGO BY SARAH ELLIOTT - 1 COMMENT

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-

out if you wish

Read More

11/26/2019

The history of Three Rivers: A place of inspiration - 3R News

When Tulare County was created in 1852, its boundaries encompassed 24,231

square miles from Mariposa County on the north to Los Angeles County on the

south and westward to the Coast Range and east to the Utah Territory. Near the

geographical center of these far-flung political boundaries was a remote river

canyon inhabited by about 2,000 Indians and containing a wealth of natural beauty.

The first white settler arrived in 1856. That man, a cattleman named Hale Dixon

Tharp (1829-1912), settled on Horse Creek near its confluence with the Kaweah

River (today Lake Kaweah). During the 1860s, other stockmen and ranchers began

to locate along the various forks of the Kaweah River. Much of the land being

claimed in the area was under the provisions of the Homestead Act of 1862, which

allowed a settler to occupy 160 acres, or 320 acres for a man and wife.

Early homesteads were located along the

South, Middle, and North forks of the Kaweah

River. Following the discovery of silver in

1872 and the subsequent creation of the

Mineral King Mining District in 1873, a trail

built by John Meadows (who later founded

Silver City near Mineral King) was extended

from the growing foothills community to link

The Kaweah River, and the availability of

with a stock trail that led from Milk Ranch into

year-round water, also made Three Rivers an

the Mineral King valley. In 1879, the Meadows

attractive place to settle.

Trail was improved to accommodate

prospectors and travelers who made their way up the East Fork. This wagon road

became known as the Mineral King Road.

On Sept. 9, 1873, Cove School opened, the first school in what was to become

known as Three Rivers. It was located in an area known as Cherokee Flat (present-

day Cherokee Oaks subdivision). As small settlements grew along each fork of the

Kaweah River, other schools were established. In 1927, local voters approved

unification and the Three Rivers Union School District was formed. In 1928, a new

building was constructed along State Highway 198 and all the local school districts

merged into one.

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-

out if vou wish. Accept Read More

11/26/2019

The history of Three Rivers: A place of inspiration - 3R News

named for the North, South, and Middle forks of the Kaweah River, which converge

nearby.

In 1886, the Kaweah Colony was established as a tent camp at Advance on the

North Fork. The utopian socialists began to attract attention, both locally and

nationwide, with the building of a road to access timber claims in the Giant Forest.

On May 17, 1890, an application for the

Kaweah Post Office at Advance was

granted. In 1910, the current 10-by-12-foot

structure was constructed with a materials

cost of about $15 and was moved several

times to accommodate its patrons. In 1926,

the post office was moved to its present

location on North Fork Drive. On Oct. 24,

The historic Kaweah Post Office.

1948, it was designated a State Historic

Landmark.

Having their sights set on Giant Forest timber that included giant sequoia trees, the

Kaweah colonists inadvertently fueled a conservation movement that led to the

establishment of Sequoia National Park (California's first national park and the

nation's second) in September 1890. In 1892, internal strife and the failure to

procure timber claims contributed to the demise of the Kaweah Colony. Many

members packed up and left, but a few of the original colonists and their

descendants stayed and settled in Three Rivers.

Travel and Tourism

After Congress established Sequoia National Park, Three Rivers began to cater to

an increasing number of visitors to Giant Forest and Mineral King (which was not

added to Sequoia National Park until 1978). In 1892, James Barton deeded the

North Fork road right-of-way to Tulare County for one dollar, and it was extended to

link with the Colony Mill Road, providing public access to the newly created national

park.

In 1894 the Britten brothers built the two-story Three Rivers odge in the vicinity of

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-

out if you wish.

Accept

Read More

11/26/2019

The history of Three Rivers: A place of inspiration - 3R News

In 1899, John Broder and Ralph Hopping>opened Camp Sierra on the North Fork

and guided visitors into the park on horseback. In 1900, they started the first stage

line into Sequoia Park, which traveled to road's end at the old Colony Mill. From

there, travelers would walk or ride horseback remaining six miles to Round Meadow

in Giant Forest to stay at Broder and Hopping's camp.

In 1903, the federal government completed a

road extension linking the eight-mile

segment of Colony Mill Road with Giant

Forest. This route remained the main

entrance to Sequoia until the completion of

State Highway 198 in 1923 and, after five

years of construction, the opening of the 18-

mile Generals Highway in 1926.

The Generals Highway in Sequoia National

Park is little changed since 1926.

In 1935, the park-to-park highway opened,

linking Sequoia National Park with General Grant National Park (which was

enlarged and became Kings Canyon National Park in 1940). Also in 1935, the Three

Rivers Airport opened, dedicated as Jefferson Davis Field. The one-runway airport

closed to air traffic in 1970.

Vital Services

In September 1898, Mount Whitney Power and Electric Company began

construction on a flume along the East Fork of the Kaweah River using redwood

lumber from Atwell's Mill near Mineral King and built a hydroelectric power plant

(located near the present-day junction of State Highway 198 and Mineral King

Road).

On June 29, 1899, when the water first surged through Kaweah No. 1, transformed

to energy, and was delivered to Visalia, it was called "an enterprise of mammoth

proportions." On that day, electricity was transmitted a greater distance than had

ever been accomplished before anywhere. Ironically, Three Rivers did not benefit

immediately from this electrical engineering feat, although it was the settlement

closest to the source of the hydroelectric power.

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-

out if you wish

Read More

11/26/2019

The history of Three Rivers: A place of inspiration - 3R News

refrigeration, and irrigate their ranches. In 1905, Kaweah Powerhouse No. 2

(located on present-day Kaweah River Drive) was completed, and in 1913, Kaweah

Powerhouse No. 3 (Ash Mountain) was built. Mount Whitney Power and Electric

Company was acquired by Southern California Edison in 1917. In 1947, the original

redwood flume was replaced with metal siding.

In 1904, the first telephone line was installed in Three Rivers. The "farmer's phone

line" connected Three Rivers residents to each other and to the Valley a decade

later. In 1909, Sequoia Hall was built, which became the community civic center. In

1910, Adam Bahwell donated land to the County of Tulare for the creation of the

Three Rivers Cemetery.

On Dec. 23, 1955, a 100-year flood on the

Kaweah River washed away homes and

bridges and marooned many sections of

Three Rivers. Downtown Visalia and

hundreds of acres of agricultural land

downstream also flooded. As a result, in

1962, Terminus Dam was constructed. Lake

Kaweah, with a capacity of 150,000 acre-feet,

The devastation of the 1955 flood.

was created to provide downstream flood

control and storage for irrigation water supply, as well as recreation and hydropower.

In 2004, 450-ton fusegates were installed, the largest in the world, to increase flood

protection and storage capacity to 185,000 af.

In 1955, the County of Tulare built the South Fork Fire Station. In 1970, the Three

Rivers Community Services District was formed. The government entity was created

to monitor water quality and to oversee any other general services necessary for the

safety and protection of the unincorporated foothills community of Three Rivers.

FILED UNDER: THREE RIVERS HISTORY

About Sarah Elliott

Contact SaraharRiversNews.com

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-

out if vou wish. Accept

Read More

-- History of Three Rivers, CA, Kaweah Colony, Lemon Cove, Woodlake

Page 1 of 4

Home

Advertise

Subscribe

Submit News

Contact Us

About TKC

Search

News and Information of KAWEAH COUNTRY - Three Rivers,

Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, Lemon Cove and Woodlake

Visitor Information:

Kaweah Colony Sequoia and Kings National Parks I Lemon Cove Woodlake

Three Rivers

Sequoia National Park

Kings Canyon National Park

The History of Three Rivers, California

Real Estate

Hotels

A place of inspiration, now and then

Restaurants

Shopping

Attractions

After reading "The History of Three Rivers" below,

Hiking

see "Stories from the Past,"

Local History

and get to know some of those

Travel Information

who have called Three Rivers home

Newspaper:

Weekly News and Features

Weekly Weather

Early Settlement

Calendar of Events

Property Rentals

When Tulare County was created in 1852, its

Columns/ Opinions

boundaries encompassed 24,231 square miles from

Readers Poll

Mariposa County on the north to Los Angeles County

Newspaper Archives

on the south and westward to the Coast Range and

KAWEAH KAM:

east to the Utah Territory. Near the geographical

Live Web Cam of Sequoia

center of these far-flung political boundaries was a

National Park, the High Sierra

remote river canyon inhabited by about 2,000 Indians

and Three Rivers, CA

and containing a wealth of natural beauty.

One of the oldest homes in

Three Rivers

can still be seen on

Yet, for all its scenic wonders, the isolated canyon at

Old Three Rivers Drive,

the site of the

the western base of the southern Sierra Nevada

first permanent settlement

remained virtually unexplored for several more years.

in the community

that included a store, lodge,

The first white settler arrived in 1856. That man, a

and stage stop.

cattleman named Hale Dixon Tharp (1829-1912),

settled on Horse Creek nears its confluence with the Kaweah River.

During the 1860s, other stockmen and ranchers began to locate along the various

Site Map

forks of the Kaweah River. Much of the land being claimed in the area was under the

provisions of the Homestead Act of 1862, which allowed a settler to occupy 160

BOOKMARK

acres, or 320 acres for a man and wife. Early homesteads were located along the

RSS FEED

South, Middle, and North forks of the Kaweah River.

Following the discovery of silver in 1872 and the subsequent creation of the Mineral

King Mining District in 1873, a trail, built by John Meadows (who later founded

Silver City near Mineral King), was extended from the growing foothills community

to link with a stock trail that led from Milk Ranch into the Mineral King valley. In

1879, the Meadows Trail was improved to accommodate prospectors and travelers

who made their way up the East Fork. This wagon road became known as the

Mineral King Road.

In 1879, the name of Three Rivers was suggested by Louisa (Mrs. Lorenzo)

Rockwell, and an application was filed for a post office. The community was SO

http://kaweahcommonwealth.com/threerivershistory.htn

3/22/2010

History of Three Rivers, CA, Kaweah Colony, Lemon Cove, Woodlake

Page 2 of 4

named for the North, South, and Middle forks of the Kaweah River which converged

nearby.

In 1886, the Kaweah Colony was established as a tent camp at Advance on the North

Fork. The utopian socialists began to attract attention, both locally and nationwide,

with the building of a road to access timber claims in the Giant Forest. On May 17,

1890, an application for the Kaweah Post Office at Advance was granted. In 1910,

the current 10-by-12-foot structure was constructed with a materials cost of about

$15 and was moved several times to accommodate its patrons. In 1926, the post

office was moved to its present location on North Fork Drive. On Oct. 24, 1948, it

was designated a State Historic Landmark.

Having their sights set on Giant Forest timber that included giant sequoia trees, the

Kaweah colonists inadvertently fueled a conservation movement that led directly to

the establishment of Sequoia National Park (California's first national park and the

nation's second) in September 1890. In 1892, internal strife and the failure to procure

timber claims led to the demise of the Kaweah Colony. Many members packed up

and left, but a few of the original colonists and their descendants stayed and settled in

Three Rivers. For a comprehensive history of the Kaweah Colony, visit the

publisher's website: www.ravenriverpress.com.

Travel and Tourism

After Congress established Sequoia National Park, Three Rivers began to cater to a

increasing number of visitors to Giant Forest and Mineral King (which was not added

to Sequoia National Park until 1978). In 1892, James Barton deeded the North Fork

road right-of-way to Tulare County for one dollar, and it was extended to link with

the Colony Mill Road, providing public access to the newly created national park. In

1894, the Britten brothers built the two-story Three Rivers Lodge in the vicinity of

the South Fork (later known as Old Three Rivers). In 1897, Noel and Nellie Britten

opened the area's first general merchandise store in that same location. In 1899, John

Broder and Ralph Hopping of Three Rivers opened Camp Sierra on the North Fork

and guided visitors into the park on horseback. In 1900, they started the first stage

line into Sequoia Park, which traveled to road's end at the old Colony Mill. From

there, travelers would walk or ride horseback four miles to Round Meadow in Giant

Forest to stay at Broder and Hopping's camp.

In September 1898, Mount Whitney Power and Electric Company began construction

on a flume along the East Fork of the Kaweah River using redwood lumber from

Atwell's Mill near Mineral King and built a hydroelectric power plant (located near

the present-day junction of State Highway 198 and Mineral King Road). On June 29,

1899, when the water first surged through Kaweah No. 1, transformed to energy, and

was delivered to Visalia, it was called "an enterprise of mammoth proportions." On

that day, electricity was transmitted a greater distance than had ever been

accomplished before anywhere.

Ironically, Three Rivers did not benefit immediately from this electrical engineering

marvel, although it was the settlement closest to the source of the hydroelectric

power. It wasn't until 1926, after a campaign by the Three Rivers Woman's Club, that

community members had the luxury of electricity to light their homes, provide

refrigeration, and irrigate their ranches. In 1905, Kaweah Powerhouse No. 2 (located

on present-day Kaweah River Drive) was completed, and in 1913, Kaweah

Powerhouse No. 3 (Ash Mountain) was built. Mount Whitney Power and Electric

Company was acquired by Southern California Edison in 1917. In 1947, the original

redwood flume was replaced with metal siding.

In 1904, the first telephone line was installed in Three Rivers, The "farmer's phone

line" connected Three Rivers residents to each other and to the Valley a decade later.

In 1909, Sequoia Hall was built, which became the community civic center. In 1910,

http://kaweahcommonwealth.com/threerivershistory.htm

3/22/2010

Mineral King Visitor Center

Page 1 of 4

Welcome to Mineral King

Silver City

Timber Gap

Atwell Mill

9450Ft

(Private community)

6540ft

2387m

6935F+

1993m

21 14m

Sawtpath

Pass

Monarch

Lakes

Cold Springs

A

Pack Station

7830F+

2387m

a

Mosquito

Lakes

Eagle

Lake

Franklin

Lakes

White Chief

Lake

Farewell Gap

Mineral King Valley, an open glacial canyon hemmed in by the peaks of the Great Western Divide, has a

special place in the hearts of many park visitors. Accessible only by a long, slow-going road, the valley is

a place where nature, not man, dominates. This road to this area closes from November 1 to late May.

Road is steep. RVs and trailers strongly discouraged.

Mineral King first gained recognition in the early 1870's when silver was discovered in the valley. Miners

rushed to the area in 1873. The mines never produced, but the Mineral King Road, built by a mining

company in 1879, did open the area to logging, hydro-electric development, tourism and the building of

summer cabins. For many years, the area was a designated game refuge within the national forest.

The valley and surrounding peaks of Mineral King, some 12,600 acres, were transferred from the national

forest to Sequoia National Park by act of Congress in September, 1978. This ended close to 20 years of

controversy over a proposed ski resort development.

What would you like to know about Mineral King?

How do I get there?

What is the weather like?

What facilities are available?

What ranger-guided activities are available?

What can I see on my own?

What hiking trails are in the area?

I am interested in backpacking in the Mineral King area.

Warning, Marmots!

Each spring and early summer, the marmots of Mineral King dine on rare delicacies in

this alpine valley. Their fare includes radiator hoses and car wiring! Like bears, jays and

ground squirrels, marmots have not only become accustomed to visitors, they have

http://www.nps.gov/archive/seki/mkvc.htm

4/10/2010

Mineral King Visitor Center

Page 2 of 4

learned that people are a source of food.

In the parking areas some marmots feast on car hoses and wires. They can actually disable a vehicle. On

several occasions, marmots have not escaped the engine compartment quickly enough and unsuspecting

drivers have given them rides to other parts of the parks; several have ridden as far as southern

California!

The whole thing sounds ridiculous, but it's true. If you visit Mineral King, especially during the spring,

check under you hood before driving away. Let the rangers know whether or not your vehicle has been

damaged. And don't forget, marmots also love to feast on boots, backpacks, and other equipment.

Points of Interest in the Mineral King area

Atwell (Skinner) Grove: This sequoia grove was partially logged in the 1890's. It continues onto

Paradise Ridge, giving it the highest elevation of any sequoia grove. The Paradise Peak trail explores the

upper part of the grove.

-

Atwell Mill: In a clearing across from the Atwell Mill Ranger Residence stands a large

steam engine, one of the last signs of the mill that was used for cutting timber from the

surrounding forests. Kaweah colonists leased the site after their Giant Forest claims were

disallowed. Many young sequoias have grown up around the mill site in the 75-100 years since logging

ceased.

Mineral King Valley: This unique, glacially sculpted valley exhibits a variety of rock

types, including marble, shale, schist and granite. Vegetation includes sagebrush,

pinemat manzanita, and a great variety of wildflowers that prosper in the open sun.

Cold Springs Nature Trail: The exhibits along this easy one-mile trail illustrate the natural history of

the Mineral King Valley. The trail begins in Cold Springs Campground across from the ranger station.

Sawtooth Peak (12,343') is the most prominent peak in the Mineral King area. Upper portions of the

peak are granite and shaped by glaciers. As with other peaks surrounding the valley, Sawtooth resembles

the Rocky Mountains more than the Sierras due to the predominance of metamorphic rocks in the

Mineral King area.

Mineral

Main

King

Visitor Center

http://www.nps.gov/archive/seki/mkvc.htm

4/10/2010

Mineral King Visitor Center

Page 3 of 4

Hikes in Mineral King

The elevation at the floor of the Mineral King Valley is 7500' (2286 meters). Hiking at this altitude is

strenuous. Gauge your hiking to the least fit member of your party. During the early summer, mosquitoes

can be a particular nuisance. As in all areas of the park, it is best to carry water, as the purity of the lakes

and streams along the trails cannot be guaranteed. The hikes described below are suitable for day trips,

but backcountry permits are also available for many of the areas.

Please be aware that pets are not allowed on any trails in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. In

developed areas, pets must be kept on a leash at all times.

Monarch Lakes: Upper and Lower Monarch Lakes lie at the foot of Sawtooth Peak, at the

end of a 4.2 mile (one-way) hike. This is one of the easier hikes in the Mineral King area, but

since the trail follows a west-facing slope, it is best to get an early start. The trail passes

through meadows, red fir forest, and the avalanche-scoured Chihuahua Bowl, a basin named

by hopeful miners for an area of rich mines in Mexico. It then rounds a shoulder and gives views north

and east across the Monarch Creek canyon to Timber Gap, the Great Western Divide and Sawtooth Pass.

Beyond the lakes, the trail climbs 1200' in 1.3 miles (366 meters in 2 km) to Sawtooth Pass, a strenuous

hike, but one that provides one of the grandest views in the southern Sierras. The footing on this portion

of the trail is very loose. Please use caution.

Crystal Lake: The trail to Crystal Lake (4.9 miles one-way) branches off of the Monarch Lakes Trail at

Chihuahua Bowl, passing the remnants of the old Chihuahua Mine near the south rim. It then climbs

steeply, providing panoramic views of the southern part of the Mineral King Valley, including White

Chief Peak and Farewell Gap. The trail, and the small dam on Crystal Lake were built by the Mt.

Whitney Power Company between 1903 and 1905. The Southern California Edison Co. still operates the

facility. There is no maintained trail beyond Crystal Lake.

Timber Gap: This trail follows an old mining route along Monarch Creek before branching off from the

trail to Monarch and Crystal Lakes. The open slopes surrounding the Mineral King Valley are kept free

of trees by avalanches; Timber Gap itself is protected from avalanches, and is covered with red fir which

the miners in the 1800's used for fuel and to shore up their mine shafts. From Timber Gap, you can see

north to the Middle Fork of the Kaweah River and across to Alta Peak. The hike to Timber Gap is 2 miles

one-way.

Franklin Lakes: This trail provides many views of the rainbow-colored metamorphic rocks

that attracted miners to this area in the 1870's, in the hopes of finding silver. Although the 5.4

mile one-way hike can be done as a day trip, many backpackers make these lakes their first

stop on their way over Franklin Pass to Rattlesnake Canyon, the Kern Canyon and Mt.

Whitney.

White Chief Trail: The White Chief mine, claimed by James Crabtree in 1873, made

Mineral King a household name among miners of that time. Crabtree's ruined cabin,

located near the meadow beyond the junction with the Eagle/Mosquito Lakes Trail, is

http://www.nps.gov/archive/seki/mkvc.htm

4/10/2010

Mineral King Visitor Center

Page 4 of 4

perhaps the oldest remaining structure in the Mineral King area. The 2.9 mile one-way trail to the White

Chief Bowl is a steep but scenic hike up the west side of the Mineral King Valley.

Eagle and Mosquito Lakes: The route to both of these lakes follows the same trail for

the first 2 miles, ascending steadily up the west side of the Mineral King Valley. After

it

reaches the lower rim of Eagle Basin, the trails split. The left-hand trail goes to Eagle Lake, a glacially

carved tarn 3.4 miles (one way) from the trailhead. The right-hand trail ends at Mosquito Lake #1, 3.6

miles (one way) from the trailhead, but hikers and fishermen often continue up the drainage to the upper

lakes.

Mineral

Main

National

King

VisitorCenter

Park Service

http://www.nps.gov/seki/mkvc.htm

Last update: December 11, 2002

http://www.nps.gov/archive/seki/mkvc.htm

4/10/2010

Lodgepole/Giant Forest Visitor Center

Page 1 of 4

Welcome to Lodgepole and the Giant Forest

Lodgepole

Visitor Center

6720ff

Lodgepole

Wuksachi

2048m

Hálstead

Meadow

Village

Wulverton

General

Panther

Sherman Tree

Gap

BigTrees

Trail

Giant Forest Museuri

Tharps

Log

++

Auto

Crescent Meadow

Log

0.5 Km

Tunnel Log

Morn Rock

0.51

The Lodgepole Visitor Center provides information for visitors to Giant Forest and the northern section

of Sequoia National Park, our country's second oldest National Park. Giant Forest is one of the main

visitor destinations in Sequoia. Four of the world's five largest sequoias grow here, and scenic meadows

dot the area. High ridges to the east of the area culminate in Mount Silliman and Alta Peak, both over

11,000'. Popular foot trails lead to glacial lakes, and a side road winds down to Crystal Cave, a

beautifully decorated marble cavern.

What would you like to know about Lodgepole and the Giant Forest?

How do I get there?

What is the weather like?

What facilities are available?

What ranger-guided activities are available?

What are the major sites in Giant Forest?

What day-hiking trails are in the area?

I am interested in backpacking in the Lodgepole area.

Tell me about the restoration of the Giant Forest and its transition from commercial center to

visitor day-use area.

If you are planning to visit Lodgepole and Giant Forest between November and May, please read the

information about winter access to Sequoia and Kings Canyon.

Main

Visitor Center

http://www.nps.gov/archive/seki/lpvc.htm

4/10/2010

Lodgepole/Giant Forest Visitor Center

Page 2 of 4

Seeing Giant Forest

Changes in the Sherman Tree area: A new parking lot and trail to the Sherman Tree are scheduled to

open sometime in August. Watch for signs to this new access route, which starts from the Wolverton

Road, a turn off the Generals Highway approximately one mile north of the Sherman Tree. The old

parking area and trail to the tree will close for ecological restoration and development of new trails and

exhibits.

General Sherman Tree: The General Sherman Tree is 274.9' (83.8 meters) tall, and

102.6 (31.3 meters) in circumference at its base. Other trees in the world are taller: the tallest

tree in the world is the Coast Redwood, which averages 300' 350' (91.4 106.7 meters) in

height. A cypress near Oaxaca, Mexico has a greater circumference, 162' (49.4 meters). But

in volume of wood, the Sherman has no equal. With 52,500 cubic feet (1486.6 cubic meters)

of wood, the General Sherman Tree earns the title of the World's Largest Tree.

The Congress Trail:

This 2 mile stroll begins at the Sherman Tree, and follows a paved trail through the heart of

the sequoia forest. It is recommended for first-time visitors to the Giant Forest, and for

visitors with limited time. Famous sequoias along this trail include the House and Senate

Groups, and the President, Chief Sequoyah, General Lee and McKinley Trees. An

informational trail pamphlet is sold at the visitor center book store.

The Big Trees Trail: This paved trail begins adjacent to the Giant Forest Museum, and forms a 1.2-mile

loop around Round Meadow. Signs along the way describe sequoia ecology, and this sequoia-lined

meadow is a good place to view wildflowers during the summer.

Hazelwood Nature Trail: The Hazelwood Nature Trail begins on the south side of the Generals

Highway, adjacent to the Giant Forest Lodge. Along this gentle 1 mile loop, signs tell the story of man's

relationship to the Big Trees.

The Moro Rock-Crescent Meadow Road

The Moro Rock-Crescent Meadow Road leaves the General's Highway from Giant Forest Village and

travels for 3 miles through the southwest portion of the Giant Forest. It dead-ends at a trailhead and

picnic area. This road is not recommended for trailers or RV's. In the winter, the road is closed to

vehicles, but open to cross-country skiing. Several famous attractions are located along this road.

The Auto Log: Early visitors to the Giant Forest often had difficulty comprehending

how big the giant sequoias are. To help give a sense of their size, a roadway was cut

into the top of this fallen tree. Due to rot in the log, cars can no longer drive on it, but it

remains an interesting historic feature. The Auto Log is located 0.9 miles from Giant

Forest Village on the Moro Rock-Crescent Meadow Road.

Moro Rock: The parking area for Moro Rock is 2 miles from the village. A steep 1/4

mile staircase climbs over 300' (91.4 meters) to the summit of this granite dome. From

the top, you will have spectacular views of the western half of Sequoia National Park

http://www.nps.gov/archive/seki/lpvc.htm

4/10/2010

Lodgepole/Giant Forest Visitor Center

Page 3 of 4

and the Great Western Divide. This chain of mountains runs north/south through the

center of Sequoia National Park, "dividing" the watersheds of the Kaweah River to the west and the Kern

River to the east. Also on the eastern side of the divide is Mt. Whitney, the tallest mountain in the lower

48 states. Unfortunately, because many of the snowcapped peaks in the Great Western Divide reach

altitudes of 12,000' (3657 meters) or higher, it is impossible to see over them to view Mt. Whitney from

Moro Rock. The summit of Alta Peak, a strenuous 7-mile hike from the Wolverton picnic area, is the

closest place from which to see Mt. Whitney.

The Parker Group: The Parker Group is considered one of the finest clusters of sequoias

which can be reached by automobile. It is 2.6 miles from the Giant Forest Village.

The Tunnel Log: Sequoia and Kings Canyon have never had a drive-through tree. The

Wawona Tunnel Tree, the famous "tree you can drive through", grew in the Mariposa

Grove of Yosemite National Park, 100 air-miles north of Sequoia and Kings Canyon. It

fell over during the severe winter of 1968-69. Visitors to Sequoia National Park can

drive through a fallen sequoia, however. In December 1937, an unnamed sequoia

275' (83.8 meters) high and 21' (6.4 meters) in diameter fell across the Crescent Meadow Road as a result

of "natural causes". The following summer, a Civilian Conservation Corps crew cut a tunnel through the

tree. The tunnel is 8' (2.4 meters) high and 17' (5.2 2 meters) wide, and there is a bypass for taller vehicles.

Crescent Meadow: The Crescent Meadow Road ends at a parking and trailhead area less

than 100 yards (91.4 meters) from the edge of Crescent Meadow. A popular hike from

Crescent Meadow is the 1-mile stroll to Tharp's Log, a fallen sequoia that provided a rustic

summer home for the Giant Forest's first Caucasian resident, Hale Tharp. Another easy 1 1/2

mile trail circles the meadow, which is an excellent place to view wildflowers in the summer.

Some lucky visitors to this and other meadows in the park may also have an opportunity to

see a bear. Because Crescent Meadow is a fragile environment, please stay on designated trails and walk

only on fallen logs for access into the meadows.

Ladgepole/

Main

Giant Forest

Visitor Center

Day Hikes in the Lodgepole/Giant Forest Area

More complete maps and descriptions of the trails in this area are sold at Visitor Center Book Stores at

Lodgepole, Ash Mountain, Grant Grove and Cedar Grove.

Please be aware that pets are not allowed on any trails in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. In

developed areas, pets must be kept on a leash at all times.

Tokopah Falls: The trail to Tokopah Falls starts just beyond the Log Bridge in Lodgepole

Campground. It is an easy 1.7 mile (one way) walk along the Marble Fork of the Kaweah

http://www.nps.gov/archive/seki/lpvc.htm

4/10/2010

Lodgepole/Giant Forest Visitor Center

Page 4 of 4

River to the impressive granite cliffs and waterfall of Tokopah Canyon. Tokopah Falls is

1200' (365.8 meters) high, and is most impressive in early summer, when the run-off from the melting

snowpack in the Pear Lake region upstream is at its peak.

Little Baldy Trail: The trail to the summit of Little Baldy begins 11 miles north of the Giant Forest

Village on the Generals Highway. This trail is 1.7 miles one way, and climbs 700' (213.3 meters). At an

elevation of 8044' (2451.8 meters) the granite dome of Little Baldy is an excellent location from which to

study the terrain of the Giant Forest Region.

The Lakes Trail: The popular Lakes Trail begins at Wolverton picnic area and ascends

steeply to a chain of glacial lakes. Heather Lake, the first lake on the trail, is 4 miles from

Wolverton. Camping is not permitted at Heather Lake, but backpacking permits are available

for Emerald and Pear Lakes, 5.7 miles and 6.7 miles respectively from the trailhead.

Alta Peak Trail: "Alta" means "high" in Spanish, and Alta Peak provides some of the

best views and high-country scenery within day-hiking distance of the

Lodgepole/Wolverton area. On a clear day, you can even see across the Great Western

Divide to Mt. Whitney from the summit of Alta Peak (11,204'/3415 meters). However,

the steep grades and high altitudes along this trail make it one of the most strenuous in

the western half of Sequoia National Park. Don't try this hike unless you are in good physical condition.

The 13.8 mile round-trip hike to Alta Peak begins at the Wolverton picnic area. Backcountry permits are

also available for this trail.

Ludgepile/

Main

National

Giant Forest

Visitor Center

Park Service

http://www.nps.gov/seki/lpvc.htm

Last update: August 1, 2005

http://www.nps.gov/archive/seki/lpvc.htm

4/10/2010

UNH LIBRARY

3 4600 00013965 6

John Muir Summering in the Sierra

Edited by

Robert Engberg

University of Wisconsin Press

[1984]

due

11/12

2.

CONTENTS

Illustrations

ix

Acknowledgments

xi

Preface

xiii

Introduction: Wilderness Journalism

3

Part One: Mount Shasta and the Lava Beds

17

Salmon-Breeding

20

Shasta in Winter

30

Shasta Game

39

Modoc Memories

52

Shasta Bees

59 .

Part Two: Home in Yosemite

65

The Summer Flood of Tourists

68

A Winter Storm in June

74

In Sierra Forests

79

Part Three: To Kings Canyon and

Mount Whitney's Summit

91

A New Yosemite - The King's River Valley

92

Ascent of Mount Whitney

104

From Fort Independence

113

Part Four: Return to the Sequoia Groves

121

The Royal Sequoia

123

The Giant Forests of the Kaweah

131

Tulare Levels

139

South Dome

143

Selected Sources and List of Readings

153

Index

157

vii

Mt Pinchot

KINGS CANYON NATIONAL PARK

4113m

Pinchot Pass

13495ft

3673m

1205Oft

Obelisk

2957m

9700ft

Kennedy Pass

3322m

10900ft

Granite Pass

3253m

10673ff

Converse

180

Road open summer only

Rae Lakes

Basin Grove

Mist Falls

ONION VALLEY

Boyden

South Fork

Cedar Grove

Independence

Cave

Kings River

Glen Pass

See other side for detail

3651m

Hume Lake

11978ft

Kearsarge Pass

3604m

SEQUOIA NATIONAL FOREST

11823ft

To Lone

Lookout Peak

Grant Grove

Charlotte Lake

Pine

2600m

See other side for detail

8531ft

resno

Avalanche Pass

John

80

3060m

Muir

1004Oft

Trail

Generals

INYO

Highway

NATIONAL

Stony Creek facilities

Roaring River

a

Redwood

include food, lodging, gas,

FOREST

Mountain

grocery store, and stable.

Foresters Pass

Grove

4011m

13180ft

Big Baldy

Stony Creek

JO Pass

2502m

2868m

8209ft

9410ft

Twin

Lost Grove

Lakes

Silliman Pass

3048m

10000ft

245

Dorst

R

Tokopah Falls

a

Giant Forest

Colby Pass

Pear Lake

Elizabeth Pass

3658m

To Lone

See other side for detail

3475m

12000ft

Pine

11400ft

Crystal Cave

John

High

Mt Whitney

Area open summer only

Muir

4418m

Sierra

Trail

14495ft

Whitney Portal

Trail

2550m

8367ft

Mt Muir

Bearpaw Meadow

Crabtree

TO

4272m

Trail Crest

14015ft

4170m

A

Potwisha

to

13680ft

Middle

SEQUOIA NATIONAL PARK

A

Buckeye Flat

Hospital Rock

Generals

Ash Mountain

High

Highway

Sierra

Park Headquarters

Trail

Rock Creek

Hammond

Mineral King

See below for detail

Siberian Pass

3338m

10950ft

Three Rivers

Road open

summeronly

East

Fork

Lake

Kaweah

Lookout Point

Franklin Pass

198

3597m

11800ft

Farewell Gap

3227m

10587ff

Hockett Meadow

e

Visalia and

tel Route 99

Fork Kaweah

Kern Canyon

South Fork

Coyote Pass

0

1

2

3

4

5 kilometers

3097m

North

A to

10160ft

0

1

2

3

4

5miles

T

The History of

Sequoia National Park, 1876-1926

Part II: The Problems of the Early Years

BY DOUGLAS H. STRONG

The Congressional legislation of September 25 and October 1,

1890, which created and first enlarged Sequoia National Park,

did not succeed in protecting the Sierra watershed as those who

initiated the movement for a vast forest reserve had hoped it

would. Only seven townships had been set aside for the Park, and

even this small area remained inadequately protected and was

interspersed with privately owned land. The movement begun

by George W. Stewart and others was to gain new support, how-

ever, and to culminate in the creation of the Sierra Forest Reserve

in 1893. It was from land in this reserve that Sequoia National

Park was enlarged in 1926 to its present size.

Although the first comprehensive Congressional bill provid-

ing for the reservation and protection of public forest lands was

introduced in 1871, no law was passed for the creation of forest

reserves until March 3, 1891, when Secretary of the Interior,

John Noble, managed to slip a clause into an act repealing the

timber-culture laws. This clause, which came to be known as the

"Forest Reserve Act," gave the President authority to set apart and

reserve public timberlands by presidential proclamation.1)

Agitation for a large forest reservation in the Sierra Nevada

east of Sequoia National Park, which had begun in 1889, con-

tinued after the passage of the Forest Reserve Act. The distinction

between a forest reserve and a national park was not yet clearly

defined, but this made no difference. The primary intention was

to protect the Sierra watershed by whatever means possible, In

April, 1891, Stewart stated in the Visalia Delta that the act of

October 1 should have included the crest of the Sierra and the

headwaters of all the rivers therein. Such a reservation would

have prevented the continuing deforestation of the area by fires,

cattle, and sheep. Stewart realized also that immediate action

[265]

Southern Calet.Quar. 48, 3 3 (1966):265-287.

This content downloaded from

137.49.125.110 on Thu, 13 Aug 2020 14:46:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Historical Society of Southern California

was needed if the acquisition of land rights in the high moun-

tains was to be forestalled.

John Muir and Robert Underwood Johnson, editor of the

Century Magazine, joined in the agitation for a large forest reser-

vation in the southern Sierra. In May, 1891, Muir recommended

to Johnson that a large park be established which would include

the headwaters of the Kings, Kern, and Kaweah rivers.2 Johnson

in turn acquainted Noble with Muir's ideas.3 Noble requested

additional information from Muir in September and notified

Johnson that the matter was being carefully considered. In

November Johnson published an article on Kings Canyon by

Muir which called for a great national park.5 Noble prepared to

consult with President Benjamin Harrison on the matter. Mean-

while all of the timberland in the area under consideration for a

forest reserve was withdrawn from sale or other disposal by the

Commissioner of the General Land Office.6 Yet despite all this

activity, a final decision as to boundaries had to await the out-

come of an investigation of the withdrawn townships by Special

Agent B. F. Allen.

Allen received his instructions in October, pursued his investi-

gations in the Sierra until he was driven out by snow in Decem-

ber, and returned in May, 1892, to complete the assignment.

With the aid of suggestions by John Muir and the directors of

the newly created Sierra Club, he wrote a report advocating the

formation of a large park. 8 Upon returning to Washington, Allen

received orders from Noble to work nights if necessary to deter-

mine the boundaries so that President Harrison could establish

the reserve before he left office. In February, 1893, Noble an-

nounced to Johnson that Allen's reservation included nearly

6,000 square miles, or roughly four million acres. 9 Allen found

general support for the proposed reserve among all Californians

except the sheepherders and lumbermen who had something to

lose. There appeared to be no mining activity and only a few

prospectors. On this basis Allen stated,

The conclusion of the whole matter is: That if the reservation is estab-

lished, the benefit to California will be beyond estimate; because there-

by, the sources of water supply will be guarded and preserved; the

scenic features will attract tourists from all over the world and a great

National Park established easily accessible to all her people. 10

266]

This content downloaded from

137.49.125.110 on Thu, 13 Aug 2020 14:46:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The History of Sequoia National Park, 1876-1926

(The proclamation for the reserve was ready by February 10

and received the President's signature on February 14, 1893.

Thus the Sierra Forest Reserve was created and the upper water-

shed of the San Joaquin Valley set aside. Although it was not the

first forest reserve established under the act of March 3, 1891, it

was one of the first that had been petitioned for successfully.11/

(Regrettably, the creation of the Sierra Forest Reserve did not

provide automatically for the protection of the watersheds within

its boundaries. In the Forest Reserve Act of 1891 there was no

provision for the administration necessary to protect the land set

aside. Lumbermen and sheepmen continued to treat it as un-

reserved public domain Logging was minimal due to the inac-

cessibility of the timber, but sheepherders, with nowhere else to

go, still used their traditional grazing grounds.

In 1894, a special agent of the General Land Office, T.P. Lupkin,

reported that an agent had been sent to the new San Gabriel

Forest Reserve in southern California to stop the depredations of

the sheep. After a few days the agent returned to Washington. 12

After all, what could one man do in millions of acres against

seasoned sheepherders who knew the terrain and remained pri-

marily in remote areas? Even in the rare case when an indict-

ment was obtained for some destructive deed, juries normally

freed the culprits.

As late as 1896, Professor William Dudley, who had explored

in Tulare County on both sides of the Great Western Divide in the

southern half of the Sierra Forest Reserve, reported that there

was no protection against fire, timber thieves, and sheepherd-

ers. 14 Finally, in the Sundry Civil Appropriations Act of June 4,

1897, Congress provided for a first step in an administrative pro-

gram for the protection of the forest reserves But although there

was a Division of Forestry within the Department of Agriculture,

it was the General Land Office of the Interior Department that

retained jurisdiction,

At roughly the same time, both John Muir and Professor Dud-

ley called attention to the effective protection provided by troops

in Sequoia National Park. Muir stated, "In the fog of tariff, silver,