From collection Creating Acadia National Park: The George B. Dorr Research Archive of Ronald H. Epp

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Search

results in pages

Metadata

[Series IX] Saving God's Creation (Jesup Memorial Library, June 19, 2018, Bar Harbor ME)

"Saving God's Creation

"

Jesup Denorial Library,

June 19,2018. Bar Harbor, ME

12/28/2017

Slideshow and Talk: Ron Epp, "Saving God's Creation: The Distinctively New England Roots of Land Conservation" - Jesup Memorial Library

Primary Menu

Search Our Site

Jesup Memorial Library

A Community and Cultural Center in Bar Harbor

All Events

Slideshow and Talk: Ron Epp, "Saving God's

Creation: The Distinctively New England

Roots of Land Conservation"

June 19, 2018 @ 7:00 pm - 8:00 pm

+ GOOGLE CALENDAR

+ ICAL EXPORT

Details

Organizer

Date:

Jesup Memorial Library

June 19, 2018

Phone:

Time:

(207) 288-4245

7:00 pm - 8:00 pm

Event Categories:

Community Events,

Lectures & Slideshows

Venue

Jesup Memorial Library

34 Mt. Desert Street

Bar Harbor, ME 04609 United

States + Google Map

Phone:

(207) 288-4245

e-

SION

"Saving God's creation":

Iglander 5/31/2018

Land conservation work

has New England roots

BAR HARBOR - Author

and historian Ronald H. Epp

will lead an exploration of the

history of land conservation

in New England at the Jesup

Memorial Library on Tuesday,

June 19, at 7 p.m.

Epp's talk will begin with

the Puritan belief that as

agents of God's will, nature

must be subdued for personal

needs. Three centuries later,

landscape architect Charles

Eliot established the first land

trust for the enjoyment of the

public in perpetuity. Epp will

explain how this movement

for preserving wild land began

with early environmentalists,

including Eliot, Ralph Waldo

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE JESUP MEMORIAL LIBRARY

Emerson, Henry David Tho-

reau, George Perkins Marsh,

Ronald H. Epp

Thomas Cole, Frederic Edwin

Church, Frederick Law Olmst-

ed, John Muir, Gifford Pinchot

during Acadia National Park's

sachusetts families who in-

and Theodore Roosevelt. These

centennial year by Friends of

fluenced the development of

men were troubled by the con-

Acadia. The debut of the book

conservation philanthropy led

tests between religion and so-

was a joint talk with FOA at

to "Creating Acadia National

ciety and between nature and

the Jesup that drew over 100

Park." Dozens of talks at book-

culture, and by the advent of

attendees.

stores, libraries, historical so-

industrialization, deforesta-

Epp is a historian and pro-

cieties and museums through-

tion, urbanization, population

fessor of philosophy with a

out the Northeast followed.

growth and transportation in-

background in scholarly pub-

Epp served as a consultant for

novations. They began their

lishing and academic library

the Ken Burns documentary

work to stem this by the cre-

leadership. He currently teach-

"America's Best Idea: the Na-

ation of land trusts and sanc-

es in the Presidents' College at

tional Parks" and has uncov-

tuaries.

the University of Hartford. As

ered and inventoried hidden

Epp is the author of "Creat-

part of its Distinguished Lec-

collections of documents re-

ing Acadia National Park: The

tures Series, he has been invit-

lating to the history of Acadia

Biography of George Buck-

ed to give a talk this October to

National Park and the origins

nam Dorr," the first biography

the Lenox Library Association

of the National Park Service.

of Dorr, which was published

on the impact of the Berkshires

Copies of "Creating Acadia

on the development of the na-

National Park" will be on sale

tional park on Mount Desert

that night courtesy of co-spon-

Island.

sor Sherman's Books. Con-

Epp's research over the last

tact the Jesup at 288-4245 or

two decades into the Mas-

mrice@jesuplibrary.org.

Page I 1

SAVING GOD'S CREATION:

The Distinctively New England Roots of Land Conservation

Ronald H. Epp

Jesup Memorial Library, Bar Harbor ME

June 19, 2018

I appreciate the opportunity to share with you some findings that I have

pursued since my book was launched here at the Jesup in April 2016.

This evening, I will highlight land conservation innovators, enumerate

the cultural themes distinctive to New England land conservation, and

show how developments nationwide would influence the land

conservation movement with the dawn of the 20th-century. [1]

But let us begin with a question. What came to mind when I use the

historically descriptive term "Puritans"? Perhaps you conjured up the

17th-century English Protestants who advocated simplification of

Church of England ceremonies and creeds; or those of a nonconformist

faith who insisted on a strict discipline and the righteousness and

sovereignty of God; or those intolerant of Catholicism where priests

were holier than the congregation; or those who followed a principle of

moderation and condemned what they judged to be excessive

behavior; or those immigrants aboard vessels like the Mayflower who

first landed at Plymouth in 1620? Perhaps an amalgam of these

options?

I raise this question because those who fled oppressive laws and

traditions in their homeland adhered to a set of doctrines that would

Page I 2

define American culture-and our views about what is private and what

is public-- for more than two hundred years. [2] Their religious beliefs

were shaped more by the Old Testament than the New. And none of

the new European arrivals had first-hand experience with Wilderness.

[3] Their biblical references confirmed that at one time all of the Earth

was wild. Earth was a global wilderness-vast and devoid of human

impact. [4] Yet when these immigrants stepped onto the

Atlantic shoreline, what they faced was qualitatively unlike their Old

World experience. [5] Their survival coping mechanisms--based on

biblical sources-would adjust, degrade or elevate, as the decades

rolled by. [6,7]

Many passengers bound for the New World supported John Winthrop's

claim that America was "the good land." [8] Others agreed with

Lincolnshire cleric John Cotton who referenced the biblical passage

where God appointed "a place for my people [of] Israel...[where] they

may dwell in a place of their owne, and move no more."[ll Samuel 7:10].

After all,didn't the Book of Genesis direct one to be fruitful and

multiply... have dominion over everything that moves upon the

earth? In encouraging belief in a terrestrial paradise they were aided

by timely advertising brochures that praised the fecundity of the

American soil and its capacity to produce "any grain, fruits or seeds you

will sow or plant." [9] The clergy offered no cautionary remarks about

seasonal challenges, the density of the forested landscape, and the

pockets of indigenous peoples already decimated before the Puritan

arrival. John Cotton interpreted an epidemic that decimated a

neighboring encampment of native Americans as a sign from God that

the Lord would have the English settle there.

Page 3

Bear in mind that in the Western tradition, land ownership is

entrenched in divine monarchies. European feudal systems provided

the justification for the sale, restriction of access, and inheritance

policies for land transfer. The concepts associated with private land

ownership were entirely alien to indigenous peoples and many

colonists took advantage of this exploitative opportunity.

The colonists, however, were more concerned about the threat posed

by the American wilderness to the veneer of civilization. Could the

wilderness reduce man to a condition no better than the carnivorous

animals he would face on these shores? [10] Many settlers-

predominantly middle class Englishmen and women--feared that

America might not be a New Eden but another refuge that would

present unknown challenges compared with the known difficulties that

they left behind. The surviving papers of the first settlers reveal that as

they approached this spiritual darkness they were resolved that

wilderness would inspire frugality and inventiveness, purifying and

strengthening their faith. Their leaders encourage belief that the first

order of business must be to carve a garden from the wilds, to redeem

America from its wildness. Today we are prone to understand

wilderness as positive, as part of our heritage. Yet as geographer David

Lowenthal explains, for the Puritans and successive generations

"wilderness was no 'heritage' to folk who had to cope with it; it became

one only when it no longer had to be lived in.' "("Not Every Prospect

Pleases," Landscape 12, 32 [1962-63], 19)

Yet the English were not alone in colonizing the frontier-the French

and Dutch were colonizing contested land. And within their own

enclaves, the English increasingly found a need to develop the public

Page I 4

domain to protect the general welfare from selfish individuals and

those who strayed away from the faith. [11] The well-known Salem

witch trials were expressions of mass hysteria rooted in religious

extremism and group isolation. [12]

By 1637 John Winthrop reported that Boston inhabitants were on the

verge of civil discord "for want of wood." So too at inland settlements

in Springfield and New Haven, where the lack of timber was acute. [13]

There was also growing concern about the rocky hills being denuded to

get to the mineral wealth that lay beneath. And towns responded with

legislation to prohibit the depletion of fish stock, and the slaughter of

wild pigeons even while other towns offered bounties for black birds,

jays, woodpeckers, and crows in order to protect their growing stocks.

Yet these 17tgh-century frontiersmen were decades removed from

developing democratic principles of access to forest, wildlife, and

resources.

Over the next several decades the Puritans radically altered the

appearance of the untamed landscape by transforming portions of the

virgin forest into habitable areas, delimited into what they called

settled estates where they pursued the ideal of a closely-knit society.

Crop failures, epidemics, shipwrecks, and grasshopper invasions made

many suspect that an angry God was displeased with their actions-

others increasingly felt their governing bodies in England were

inattentive; indeed, some claimed that the colonists had been

"marooned and forgotten."

Page I 5

Still later, the Jeffersonian secular philosophy enforced Puritanism by

providing settlers and frontiersmen with a clearly defined agrarian role

as pioneers of a civilized landscape where agricultural enterprise

fostered national progress on an international stage. [14] In such an

economy, federal and state rights are limited-private land ownership

remained uncontested. Natural calamities were no longer interpreted

as signs of providential disfavor. The Puritan hold on the New England

psyche was slipping. The jeffersonian dichotomy between rural good

and urban evil was later refined by Harvard historian Frederick Jackson

Turner who said: "The wilderness masters the colonist. It finds him a

European in dress, industries, tools, [and] modes of travel and

thought...Little by little he transforms the wilderness. But the outcome

is not the old Europe. The fact is that here is a new product that is

American...Thus the advance of the frontier has meant a steady

movement away from Europe, a steady growth of independence on

American lines." (The Frontier in American History, 1893). Those who

remained on their original holdings began to reconstitute an

equilibrium between nature and culture. A growing agrarian

appreciation for the harmonies of nature developed, no less than the

reflex to pillage the land. And "while the darker side of Puritanism

steadily receded in the 19th-century, the love of nature and the

inclination to steward it...persisted and expressed itself", first in New

England.

In the mother country, there was a long-standing agricultural tradition

where farmers agreed to share a common parcel on which their cattle

grazed. Caring for the land is an act of individual stewardship and

collective trusteeship; each herder has no claim to any part of the land

but rather to the use of it. [15] This mutually-beneficial sustainable

environment is threatened if a partner in the project decides to break

Page 6

with the norm and seeks additional profit by adding an additional

grazing cow. The quality of the Commons-which can be seen today as

any unregulated resource such as rivers, oceans, or the atmosphere-- is

damaged when equality is violated and individual overuse depletes a

common resource.

This issue of managing or policing shared resources we do not typically

associate with the pretty village green in a picturesque New England

village. And yet it overshadows characteristics distinctive to the New

England conservation movement [16] advanced by Charles H.W. Foster

in a 2009 Harvard University Press publication. Prior to his death in

2012, Foster had been Dean of the Yale School of Forestry and

Environmental Studies and researcher at the Harvard Forest. Foster

argued quite rightly that the New England approach to land

conservation not only preceded its application in other regions but that

our regional approach has "an enviable record of successful actions."

These are:

(1) a commitment to self-determination; (2) innovative thinking; (3) a

reliance on individual leadership as a first resort; (4) a strong

commitment to place; (5) a long history of civic engagement; and (6)

commitment to the ethical imperative of stewardship. Notice how

these characteristics manifest themselves in the following chronology.

Professor Foster and University of Maine historian Richard Judd argue

that environmentalists over the last half century have more often than

not ignored the indigenous peoples and European colonists who tilled

the soil, fished the rivers and ocean, and managed their woodlots.

Through their practical concern for what we today call sustainability,

Page I 7

they were the first practitioners of conservation, recognizing that the

scale of their behavior was limited by pressing local concerns.

The onset of the 19th-century brought the European growth of

industrialized economies to our shores, including the shift to special

purpose machinery. Mass production, railroad transportation, and the

development of the factory system first expressed itself in New

England. These changes were not the outcome of town hall decision-

making but the result of profit-based entrepreneurs who spoke

publically of themselves as constructive agents who harnessed the

power of Nature through their own human ingenuity (Peter A. Ford,

"Charles S. Storrow," 1993). A new landscape emerged, one of

expedience where resources were bent by energy and enterprise to

fuel the engines of material progress. Some of the negative effects of

industrialization we know all too well: grim employee living-if not--

working conditions, exploitation of youth, diversion of water power,

and the depletion of the land.

As the land was conquered by expanding populations, those who

traveled became sensitized to what they observed as the impacts of

expansionism. [17] Artist George Catlin's 1832-1839 travels--

recounted in his landmark Letters and Notes on the Manners,

Creatures, and Customs of the North American Indians-were actually

field trips to study and paint the indigenous population. The

consequences of advancing civilization were brought into stark relief in

Catlin's mind. In his published writings he explained that without

government intervention, the remaining American wilderness would

vanish! For the first time, the landscape of America has an advocate

insisting that selective portions should-in Carlin's words--be

Page I 8

"preserved in its pristine beauty and wildness, in a magnificent park.

There the world could see for ages to come beautiful and thrilling

specimen hold[ing] up to the view of her refined citizens and the

world, in future ages! A nation's Park, containing man and beast, in all

the wild freshness of their nature's beauty!" Catlin knew that mere love

of nature and devotion to it were insufficient-' "men would have to

take definite action to keep the great fortune which nature had given

them in trust." (Huth, 135) This is a bold concept ripe with changes that

radically departed from traditional land ownership practices.

In 1843, ornithologist and painter John Jay Audubon,[18 traveled West

to find what Catlin had described. There he found abundant evidence

of desolation which plunged him into mental darkness, later followed

by dementia. This is not the Audubon we chose to remember. Instead,

we recall the youthful Audubon in the decade between 1827 and 1838

quietly moving through the woods and wetlands; not only did he

observe bird behavior but he also shot specimens in order to use his

artistic skills to reveal their beauty in their last flourishing. [19] Few

disagree that Audubon succeeded in capturing--in the 435 hand-

colored plates included in Birds of America- - the splendor of what was

at risk because of human self-absorption. (Audubon. 2016. PBS home

video). Oddly, America's foremost clerics of Audubon's day were largely

silent on these human assaults on God's creations. [20]

Two years later, a Vermont attorney, diplomat, and philologist, George

Perkins Marsh, published Man and Nature. Having spent productive

years as the United States Ambassador to Italy, this native of

Woodstock [21] drew upon his wide-ranging nature studies in New

England and abroad. He compiled empirical data that showed that

Page |9

deforestation at the global level resulted in erosion, loss of agricultural

fertility, and the destruction of fish habitat. Marsh used historical

evidence to show that lush lands bordering the Mediterranean Sea had

become deserts, creating a desolation "almost as complete as that of

the moon."

From this data Marsh concluded that "Man is everywhere a disturbing

agent. Wherever he plants his foot, the harmonies of nature are turned

to discord." Marsh claimed that the welfare of man and nature over

generations is only achieved if man manages resources. When those

who despoil nature trump it with the utility card, Marsh argued that

"utility" was a bird of many feathers. If minerals and timber were

examples of utility, so were water and watershed. Considered by many

to be the Father of the American conservation movement, Marsh

revealed man's abuse of nature, explained its causes, and prescribed

reforms. [22]

In their day, Marsh and Audubon were not solitary conservation

advocates. Widely read was The North American Review, an influential

serial spreading progressive ideas as well as traditional Yankee values.

What their authors-first-rate scholars, clergy and other professional

men and women-articulated, was concern that modern power in

irresponsible hands could lead to new forms of human abuse against

the earth, air, and waters.

One contributors was a popular board-game designer and author Anne

Wales Abbott (1808-1908). Reflecting Charles Foster's aforementioned

standard of a strong commitment to place as well as the imperative of

Page I 10

stewardship, she wrote in 1848 that no self-respecting "Yankee land-

owner would fell a single oak without planting an acorn." She warned

that the reduction of forest areas was diminishing the water-power on

which the many of the fabric mills depended." [23] In another essay

she emphasized that individual initiative is not enough. The task of

forest improvement "is one whose importance to the commonweal

makes it the proper action of the government." Her action is both

notable and noble for she was convinced that once the public was

made aware of the importance of preserving woodlands then the public

would act collectively in the interest of conservation.

Her thinking was allied with Mary Hopkins Goodrich who not only

planted 400 trees in the Berkshires but initiated sustained actions to

elevate the condition of the commons, streets, walkways, paths,

lighting, cemeteries, and public places in Stockbridge, MA Formed in

the same year as Dorr's birth-1853-- the Laurel Hill Association that

Goodrich established is the oldest existing village improvement society,

the model for scores of other communities (including the villages on

MDI) where public engagement was newly fostered-- at a time when

town services were sorely lacking-and the evidence of environmental

degradation was increasingly evident.

But at a more conceptual level, we turn our attention to Concord MA

where the American Romantic movement wrestles with the meaning of

Nature. There a new vision emerges in the writings of Thoreau and the

Transcendentalism of Ralph Waldo Emerson-- a descendant of eight

generations of Puritan clergymen.| [24] To study nature now meant that

one had to rely on one's own resources, acknowledging that the inner

voices of sentiment and intuition spoke with finality. [25] Moreover,

Page 11

Emerson admitted that while humans derived wealth from the

commodities extracted from natural sources, he cautioned that this

exploitative value is "but temporary and mediate, not ultimate." The

Rev. William Ellery Channing paraphrased his friend when he wrote that

"Emerson and the Transcendentalists discerned more and more of God

in everything [from] "the frail flower to the everlasting stars."

Emerson's lifelong walking companion was Henry David Thoreau, and

whereas Emerson enjoyed meeting people, Thoreau hoped that his

peripatetic efforts would allow him to escape his neighbors. [26] Hills

and mountains were Thoreau's domain. He anticipated George B.

Dorr's purchase of the top of what is today called Cadillac Mountain

when he noted in his Journal for January 3, 1861: "As in many

countries, precious metals belong to the crown, so here more precious

natural objects of rare beauty should belong to the public... think that

the top of a mountain should not be private property; it should be left

unappropriated for modesty and reverence's sake, or if only to suggest

that Earth has higher uses than we put her to."

Thoreau sought the wild even in one of the tamest places-- Concord.

For "each town should have a park, or rather a primitive forest, of five

hundred or a thousand acres where a stick should never be cut for

fuel-not for the Navy, nor to make wagons, but [to] stand and decay

for higher uses-a common possession forever, for instruction and

recreation." [27] These are the places where Audubon's birds reside.

Wildness was palpable in Concord but in Maine it was unrelenting. In

his classic personal adventure, The Maine Woods, Thoreau recalled his

experiences of the "howling wildness," the deep primordial north

woods that his Puritan predecessors had tried to eradicate. [28]

Page I 12

Thoreau asked: "Why should we [not] have our national preserves,

[places] in which bear and panther, and some even of the hunter race,

may still exist-not for idle sport or food, but for inspirations and our

own true recreation? Or shall we, like villains, grub them all up,

poaching on our own national domains?"

Hudson River School painters anticipated this movement away from the

"poaching our own domains." [29] Led by Englishman Thomas Cole [30,

31] and Frederick Church [32,33] - -these artists traveled far and wide

to represent nature unspoiled by human intervention. They covered

their canvases with radiant landscapes that awakened viewers who first

admired their works in museums or publications, many then planned to

travel to the places where Hudson River School painters like Cropsey,

Durand, Innes, and Kennett found their inspiration. The practical

implication was that if these sublime Arcadian landscapes were worthy

of preservation in the foremost American museums, [34] surely the

conservation of the physical source was worth as much or more !!

Notice that value is here redirected-from artistic representation back

to its natural source. As young George Dorr worked his way through

Harvard College (1870-74), D. Appleton & Company published a two

volume set of illustrated books that was implicitly a conservation

manifesto. Appleton's Picturesque America S celebrated the entire

continent-and its first essay was "On the Coast of Maine."

Yet it was not enough to illustrate and write essays about thunderous

cataracts, lofty mountains, and undulating pastures. The citizenry of

any era lives in the here and now, fixated on the sober realities of life

and death. [35] It was commonplace to believe in the mid 19th- century

that depositing one's remains in a church burial ground increased one's

Page I 13

chances of salvation. But as cities grew, health studies suggested that

these burial grounds might be a source of disease and a cause of

epidemics. An enlightened physician and public-spirited Boston citizen,

Jacob Bigelow (1786-1879), became alarmed at the health risks in the

rapidly growing inner city. [36} He joined forces with Influential men

like Daniel Webster, Edward Everett, and Thomas Wren Ward (George

ma

Dorr's paternal grandfather), [37] and pioneered the rural cemetery

movement. [38]

Aligned with the newly formed Massachusetts Horticultural Society,

these bluebloods identified an aesthetically compelling location in

Cambridge. [39] Founded in September 1831, the natural beauty and

diverse topography of Mount Auburn Cemetery became popular both

to visit and to be interred-after all, did not this "pleasure ground"

demonstrate the kindliness of a Creator who had given the world such

natural beauty? [40] A Dorr family friend, British actress Fanny Kemble,

lightened the ambiance associated with a burial ground, referring to

Mount Auburn [41] as her favorite trysting place. Landscaped with

trees, shrubs, water features, paths, in a topographically varied setting,

the seasonally changing environment fostered belief in the continuity

of life. In time, thoughtful men and women began to ask: if we can

provide such an environment for the departed, is it not reasonable to

pursue at least as much for the living?

While new technologies offered unprecedented power over nature

they also distanced people from the organic world so dominant in the

earlier economy. [42. 43] Increasingly, the forces of Industrialization,

immigration, and population density put a premium on health and open

space. [44] Outside New England, positive steps were taken to offer a

Page I 14

sanctuary for such change. In 1853, New York State authorized on a

massive scale a portion of Manhattan Island for recreation. [45] In the

first landscape design contest in history, the proposal of Frederick Law

Olmsted and Calvert Vaux was selected over thirty-two other

applicants. Of course you have figured out that they would execute the

transformation of 778 island acres-one square mile--into a Central

Park.[46] There they pioneered an urban conservation movement, a

new era where urban-not agrarian--forces came to the forefront.

Central Park set a precedent for land conservation in the common

interest more than a decade before realization of the national park

concept at Yellowstone.

After frustrating and protracted disagreements with New York politics,

the Father of American Landscape Architecture left the Northeast in

1862 for a three year stay in Bear Valley, adjacent to the Mariposa

Grove in California's Yosemite Valley. There the western explorer and

politician John C. Fremont had purchased seventy square miles of real

estate and turned it into a massive mining operation. Having lost his

fortune, Fremont sold The Mariposa Company to a New York banker

who approached Olmsted about managing the Estate. [47] So

impressed was Olmsted by the beauty of this Valley that he issued a

report arguing analogously that such natural scenery should be

available to the public for the same reason that the water of rivers

should be guarded against private appropriation and protected against

obstruction.

Back East In the nation's Capitol, Irish-American California Senator John

Conness secured passage of the Yosemite Act of 1864 which reserved

Yosemite Valley from settlement and entrusted its care to the State of

Page I 15

California. [48] Olmsted became a Yosemite commissioner tasked with

oversight but when he called for strict regulation and public access, his

claims were suppressed by the California legislature. Not until 1891

were John Muir and others successful in establishing Yosemite National

Park. [49]

This bill contained something exceptional: a clause that the federal land

was given "under the express condition that the premises shall be held

for public use, resort and recreation and shall be held inalienable for all

times." Unlike the local scope of Central Park, Olmsted here was the

driving force behind this completely new idea-- of creating a park as a

playground for the nation. Olmsted's biographer emphasized that the

expansion of the concept of a park was the beginning of what would

become a half century later The National Park System. For this was the

first time that a national government set aside federal land for the

explicit purpose of conservation.

The motive? In Olmsted's eyes, the answer was the recuperative power

of natural scenery. Nature heals, fresh air is good, and this sort of

change in everyday habits improves health and intellectual vigor. Have

no doubt. Unlike Central Park, Yosemite was real wilderness and yet it

could be as powerful a civilizing force as urban parks, providing an

escape from the cramped, confined and controlling effects of town and

city life. In Olmsted's own words, "an enlarged sense of freedom is to

all, at all times, the most certain and the most valuable gratification

afforded by a park."

Page I 16

Four years before John Muir arrived (1868) in California, Olmsted

realized that there were management issues that could not be ignored.

recording

regailing,

The nation was still

caught in the grip of the Civil War, yet Olmsted

from

pointed out that "the mere existence of some great natural wonder

was not enough; it was essential that someone with both vision and

initiative made the place attractive and acceptable to the public, and in

addition provide [the] means by which the public could reach it in

convenience and safety."

In the territories of the far West, John Wesley Powell's geographic

exploration of the arid Colorado River basin in 1869 led to federal

proposals to enforce irrigation and watershed systems across state

lines, proposals resisted in Congress but not ignored on the East coast.

Similarly, surveyors, artists, and railroad entrepreneurs came to the

conclusion that more than two million acres in the Montana and

Wyoming territories needed to be preserved from commercialization.

Sensational accounts of Yellowstone's geology -with accounts of

shooting geysers, boiling streams, sulfuric pits, stunning canyons, and

majestic waterfalls-- were featured in newspapers and magazines. [50,

51]

Proponents used the Yosemite Act in late 1871 as precedent to save the

massive Yellowstone from private development; yet to permanently

shut the door on settlement of an area comparable to several eastern

states, departed from the long standing national policy of transferring

federal lands into private ownership (e.g., through homesteading). But

there was opportunism quickly seized by the Northern Pacific Railroad

which adopted Yellowstone as a destination for tourists aboard its

trains. Those railroads that traversed the Plains' States attracted

Page I 17

hunters at this time who found great joy in slaughtering buffalos from

moving trains. [52] Between 1870-1875 six million bison were killed--

and the species neared extinction. No other resource in this country

"has ever been destroyed in so short a time and with so little protest."

[53] (Hans Huth, Nature and the American, 163). The conservation

concept had again been broadened. Thereafter, some wildlife was

aligned with land and water conservation.

In January 1872 the Yellowstone bill was introduced in Congress and it

quickly became apparent that neither Wyoming or Montana could be

assigned management responsibility--they were not yet States. [54] On

March 1st President Grant signed the bill to "set aside a public park or

pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people."

While that story unfolded, back East a precocious 23-year old

topographical engineer named Verplank Colvin (1847-1920), issued a

report in the early 1870's detailing the extent of deforestation in the

Adirondacks. [55] Not only did lumbering poise a threat to the Erie

Canal, but the erosion that resulted-- as winter snowmelt emptied into

the Hudson River-- was "laden with disaster for communities

downstream [i.e. Manhattan]." In 1872, under sponsorship of the State

of New York, Colvin was appointed Adirondack Survey Superintendent

charged with surveying with strict accuracy-- using triangulation--the

millions of acres that constitute the Adirondacks. Early into this 30 year

project, he proposed the creation of "an Adirondack Park or timber

preserve...[set aside] for posterity." It took more than a decade for The

Forest Preserve Act to remove logging from state owned land.

Moreover, this report came on the heels of the 1869 publication of

Adventures in the Wilderness, or Camp Life in the Adirondacks by

Page 18

William Henry Harrison Murray, aka Adirondack Murray. [56] This

extremely influential book whetted an appetite for the North Woods

and engagement through travel with the woodsmen who inhabited this

wilderness. [57]

Albany journalist Samuel H. Hammond, a hunter and conservationist

like Audubon, returned from a 1857 Adirondack camping trip and

worried what modern commerce would do to wild places. He then set

pen to paper and wrote these startling words that resonated far and

wide : "Had I my way, I would mark out a circle of a hundred miles in

diameter, and throw around it the protecting aegis of the [New York]

Constitution. I would make it a forest forever." In the succeeding

decades recreationists like Hammond, Murray enthusiasts, and New

Yorkers who sought an antidote for the encroachment of technological

power, came together.

In western New York, a group of enthusiasts called Free Niagara

crusaded against expansion of the commercial exploitation of the

Niagara River. The Robber Baron era was at hand and with it the

formation of monopolies and the attendant corruption. [58] Sheds,

refuse dumps, and the pollution from the Niagara power plant

downriver from the Falls gave rise to public protests that resulted in

legislation creating in 1885 the Niagara Reservation, America's oldest

state park. [59] And who was the leader of the Free Niagara

movement? None other than Olmsted! Manhattan residents and

visitors had witnessed the benefits of their new Central Park and those

voices resonated to Albany and beyond. University of Maine

environmental historian R.W. Judd rightly argues that New Yorkers like

their New England neighbors at the end of the 19th-century "were more

Page 19

alienated from nature and at the same time, more attuned to the

natural elements in the landscape around them." [60] (Second Nature,

2014.95)

That very same year (1885) the Forest Preserve was established in the

Adirondack mountains [61], though we New Englanders should take

pride in the fact that it was Arnold Arboretum Director Charles Sprague

Sargent who proposed the words "forever kept wild as forest lands." In

1892 the Adirondack Park was created. [62] Finally, in 1894 a

constitutional convention closed loopholes to the new law-and in

Article 7, section 7 it is affirmed in the State Constitution that State

lands "shall be forever kept as wild forest lands... not leased, sold or

exchanged, or be taken by any corporation, public or private, nor shall

any timber thereon be sold, removed or destroyed." The

implementation of 'forever wild' signaled the ascendancy of a specific

type of utility over another. A choice between wood and water. And

water won! As a consequence, New York voters by popular vote

affirmed a key axiom of the conservation ethic as a rule of law."

Here in Maine, the forests were understood in the last decade of the

19th-century as critical to the survival of its fish and game-not to

mention their attraction to vacationers. Yet it was not until 1891 that a

Forest Commission was created to oversee development of a forest

policy; many insisted that the forests were inexhaustible. Similar issues

faced New Hampshire residents where poor timber practices in the

White Mountains irritated the Rev. John E. Johnson during his years at

Dartmouth College. His pamphlet, the "Worst Trust in the World," was

nothing less than a diatribe against the New Hampshire Land Company

which had lobbied the State legislature successfully to become the

Page I 20

region's dominant landowner. The NELC then refused to sell lumber to

local loggers for their milling operations. Johnson called this process

"refrigeration," a deliberate act that resulted in business failures, the

defaulting of commercial and residential mortgages, and the company

picking up the available properties for a song. More than a decade

later in 1911 the U.S. Congress passed one of the most significant

pieces of conservation legislation in U.S. political history. The Weeks

Act authorized the federal government to purchase land to protect the

watersheds of navigable streams and rivers. Not only was the White

Mountain National Forest an outcome, but over the decades more than

22 million acres of national forests were secured and managed in 26

states. The Weeks Act made the nation's forests national. Through it,

forest conservation became continental.

In conclusion, we have shown that the Puritans approached the New

World as the perceived agents of God's Will, invoking biblical directives

about subduing the landscape to serve their personal ends. This

approach is clearly at odds with another biblical interpretation: that

America was the Garden of Eden, a paradise altered through the

commission of sin. As the boundaries of the managed North American

landscape were pushed Westward, notions of public space-the

Commons-were an incidental corrective to private exploitation. While

the collective roots of New England land conservation are distinctive to

this region, their piecemeal application of these characteristics outside

the region propelled the public-spirited men and women highlighted in

this lecture to reformulate the Puritan model. By the end of the 19th-

century the innovative approaches of these outsiders returned to the

Northeast where they were incorporated into the Progressive Agenda

of the new century. To repeat the aforementioned Olmsted

prescription:

Page 21

"It [is] essential that someone with both vision and initiative make

[some great natural wonder] attractive and acceptable to the public,

and in addition provide [the] means by which the public could reach it

in convenience and safety." Saving God's creation would now be at

the forefront of the national agenda.

Jesup 6.18

Slideshow: Saving God's Creation

1. "Embarcation of the Pilgrims," Robert W. Weir. 1844.

2. Mayflower Compact signing enroute to America. J.L. Ferris.

3. "Mayflower in Plymouth Harbor," William Halsall. 1882.

4. Mayflower arrival

5. Colonists move inland

6. First sermon ashore. J.L. Ferris. 1900.

7. John Winthrop

8. John Cotton

9. Imagined Thanksgiving

10. Native americans attack settlement

11. Salem witch trial, 1682.

12. Founders Memorial. Boston Common.

13. St. Gauden's sculpture of Samuel Chapin. Springfield, MA

14. Agrarianism

15. Medieval English Manor estate map with "Commons"

16. Charles H. W. Foster

17. George Catlin & Native American

18. John Jay Audubon

19. Birds of America.

20. George Perkins Marsh (1801-1882). Man and Nature.

21. Woodstock VT home. Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller NHP.

22. North American Review

23. Author game of Anne Abbott

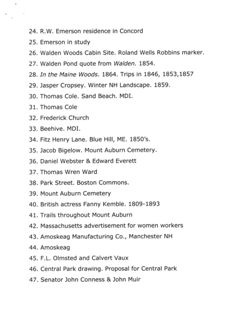

24. R.W. Emerson residence in Concord

25. Emerson in study

26. Walden Woods Cabin Site. Roland Wells Robbins marker.

27. Walden Pond quote from Walden. 1854.

28. In the Maine Woods. 1864. Trips in 1846, 1853,1857

29. Jasper Cropsey. Winter NH Landscape. 1859.

30. Thomas Cole. Sand Beach. MDI.

31. Thomas Cole

32. Frederick Church

33. Beehive. MDI.

34. Fitz Henry Lane. Blue Hill, ME. 1850's.

35. Jacob Bigelow. Mount Auburn Cemetery.

36. Daniel Webster & Edward Everett

37. Thomas Wren Ward

38. Park Street. Boston Commons.

39. Mount Auburn Cemetery

40. British actress Fanny Kemble. 1809-1893

41. Trails throughout Mount Auburn

42. Massachusetts advertisement for women workers

43. Amoskeag Manufacturing Co., Manchester NH

44. Amoskeag

45. F.L. Olmsted and Calvert Vaux

46. Central Park drawing. Proposal for Central Park

47. Senator John Conness & John Muir

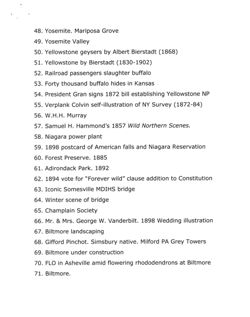

48. Yosemite. Mariposa Grove

49. Yosemite Valley

50. Yellowstone geysers by Albert Bierstadt (1868)

51. Yellowstone by Bierstadt (1830-1902)

52. Railroad passengers slaughter buffalo

53. Forty thousand buffalo hides in Kansas

54. President Gran signs 1872 bill establishing Yellowstone NP

55. Verplank Colvin self-illustration of NY Survey (1872-84)

56. W.H.H. Murray

57. Samuel H. Hammond's 1857 Wild Northern Scenes.

58. Niagara power plant

59. 1898 postcard of American falls and Niagara Reservation

60. Forest Preserve. 1885

61. Adirondack Park. 1892

62. 1894 vote for "Forever wild" clause addition to Constitution

63. Iconic Somesville MDIHS bridge

64. Winter scene of bridge

65. Champlain Society

66. Mr. & Mrs. George W. Vanderbilt. 1898 Wedding illustration

67. Biltmore landscaping

68. Gifford Pinchot. Simsbury native. Milford PA Grey Towers

69. Biltmore under construction

70. FLO in Asheville amid flowering rhododendrons at Biltmore

71. Biltmore.

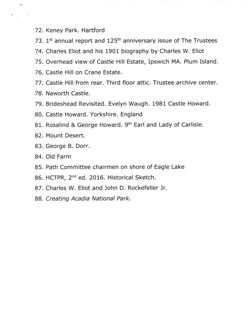

72. Keney Park. Hartford

73. 1st annual report and 125th anniversary issue of The Trustees

74. Charles Eliot and his 1901 biography by Charles W. Eliot

75. Overhead view of Castle Hill Estate, Ipswich MA. Plum Island.

76. Castle Hill on Crane Estate.

77. Castle Hill from rear. Third floor attic. Trustee archive center.

78. Naworth Castle.

79. Brideshead Revisited. Evelyn Waugh. 1981 Castle Howard.

80. Castle Howard. Yorkshire. England

81. Rosalind & George Howard. 9th Earl and Lady of Carlisle.

82. Mount Desert.

83. George B. Dorr.

84. Old Farm

85. Path Committee chairmen on shore of Eagle Lake

86. HCTPR, 2nd ed. 2016. Historical Sketch.

87. Charles W. Eliot and John D. Rockefeller Jr.

88. Creating Acadia National Park.

4/20/2018

XFINITY Connect Inbox

questions about your visit on June 19th

Ruth Eveland

5:00 PM

To Ronald & Elizabeth Epp

alister

Dear Ron,

I was talking this afternoon with Nancy Poteet, chair of our Advancement Committee, and

Lee Bonta, our new full-time Director of Development, and we have a couple of questions.

1. Would it be possible for you to send a paragraph or two summarizing your planned

talk? Yours is one of our summer events which we are hoping will help to open a

few doors for us. I didn't have an opportunity to check with Mel or Kayla to see if

you have already sent them something we could use, so if you have please pardon

the double-ask.

2. Would you be willing to participate in something like a light supper at the Jesup on

Monday, the night before your talk? We are thinking about inviting some of the

people on our cultivation list who we believe will be interested in attending your talk

yes

and who might additionally value the opportunity to meet with you. We'd want to

have on display some of maps from the Deasy-Chapman collection as well,

particularly, of course, the one with Dorr's handwriting on it.

I hope that spring is finally arriving in your new location. We've had a few random nice

days, but not yet any sequence of them. They promise it for early next week and we are

hopeful. We have survived this winter and have earned our spring!

Thanks,

Ruth

Ruth A. Eveland

Director

Jesup Memorial Library

34 Mt. Desert Street

Bar Harbor, Maine 04609

207/288-4245 (library); 207/610-2355 (cell)

reveland@jesuplibrary.or

www.jesuplibrary.org

Jesup Memorial Library: "Anchor to the Past; Chart to the Future"

5/21/2018

XFINITY Connect Inbox

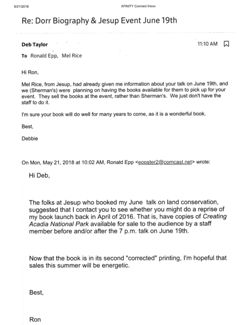

Re: Dorr Biography & Jesup Event June 19th

Deb Taylor

11:10 AM

To Ronald Epp, Mel Rice

Hi Ron,

Mel Rice, from Jesup, had already given me information about your talk on June 19th, and

we (Sherman's) were planning on having the books available for them to pick up for your

event. They sell the books at the event, rather than Sherman's. We just don't have the

staff to do it.

I'm sure your book will do well for many years to come, as it is a wonderful book.

Best,

Debbie

On Mon, May 21, 2018 at 10:02 AM, Ronald Epp wrote:

Hi Deb,

The folks at Jesup who booked my June talk on land conservation,

suggested that I contact you to see whether you might do a reprise of

my book launch back in April of 2016. That is, have copies of Creating

Acadia National Park available for sale to the audience by a staff

member before and/or after the 7 p.m. talk on June 19th.

Now that the book is in its second "corrected" printing, I'm hopeful that

sales this summer will be energetic.

Best,

Ron

Viewer Controls

Toggle Page Navigator

P

Toggle Hotspots

H

Toggle Readerview

V

Toggle Search Bar

S

Toggle Viewer Info

I

Toggle Metadata

M

Zoom-In

+

Zoom-Out

-

Re-Center Document

Previous Page

←

Next Page

→

[Series IX] Saving God's Creation (Jesup Memorial Library, June 19, 2018, Bar Harbor ME)

| Page | Type | Title | Date | Source | Other notes |

| 2 | Web Page | Slideshow and Talk: "Saving God's Creation: The Distinctively New England Roots of Land Conservation | 06/19/2018 | Jesup Memorial Library | - |

| 3 | Newspaper Article | Land conservation work has New England roots | 05/31/2018 | Mount Desert Islander | - |

| 4-24 | Lecture | Saving God's Creation: The Distinctively New England Roots of Land Conservation Talk at Jesup Memorial Library | 06/19/2018 | Ronald Epp | - |

| 25-28 | List | Slideshow: Saving God's Creation | N/A | Ronald Epp | - |

| 29 | Email from Ruth Eveland to Ronald Epp: questions about your visit on June 19th | 04/20/2018 | Ronald Epp | Annotated by Ronald Epp | |

| 30 | Email from Deb Taylor to Ronald Epp: Re: Dorr Biography & Jesup Event June 19th | 05/21/2018 | Ronald Epp | - |

Details

06/19/2018