[Series IX] Theodore Roosevelt and the Mt Desert Triumvirate (Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site, Buffalo NY)

- Home

- [Series IX] Theodore Roosevelt and the Mt Desert Triumvirate (Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site, Buffalo NY)

From collection Creating Acadia National Park: The George B. Dorr Research Archive of Ronald H. Epp

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Search

results in pages

Metadata

[Series IX] Theodore Roosevelt and the Mt Desert Triumvirate (Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site, Buffalo NY)

"Theodore Roosevelt and the

Mount Desert Triumvirate"

Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural

10/3/21, 7:52 PM

About Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural Site

About

The TR Site is a unit of the National Park Service, the only NPS location in Western New

York. Since its inception, the Site has been managed by a local board of trustees, the

Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural Site Foundation, through a cooperative agreement with

NPS.

The Museum

Now you can step back in time and into the world that TR knew. Walk where he walked,

see and hear the challenges he faced, and get a sense of what it was like to lead our

nation during such a pivotal time in its history. View More

Our Foundation

https://www.trsite.org/about

2/8

Page |1

Theodore Roosevelt & the Mount Desert Triumvirate

September 27, 2016

THEODORE ROOSEVELT INAUGURAL SITE

I want to thank Curator Lenora Henson for this opportunity to

return yet again to western New York where nearly fifty years ago

I majored in history at the University of Rochester and then

pursued graduate work in philosophy for my doctorate at the new

State University of New York at Buffalo.

Thank you for giving me the opportunity to speak this evening

about little known-and greatly underappreciated-historic

conservation developments in Maine that dovetailed with the rise

of President Roosevelt's environmental agenda. Indeed, I argue

in my biography-Creating Acadia National Park-- that without

Roosevelt's "Bully Pulpit," many conservation efforts at the local,

state, and regional level would surely have failed.

According to biographer Andrew Vietze (Becoming Teddy

Roosevelt. Camden: DownEast Books, 2010) the State of Maine

was "a crucible of sorts for Roosevelt and the seeds of

conservation that he would go on to plant were sown right here

[in Maine] when he was an impressionable young man."

Experience in lumber camps and on hunting adventures with

Island Falls guide Bill Sewall hardened TR during his Harvard

years; an ascent of Mt. Katahdin he described in "My Debt to

Maine" as 'qualified joy'. After graduation, TR spent time on

Mount Desert Island to inspire his writing of the authoritative

Naval War of 1812 (1882).

Page I 2

Few recall today Roosevelt's remarkable September 6th 1901 train

ride from Burlington VT across New York State to the bedside of

the critically wounded President William McKinley. The

assassination attempt removed the vice-president from the

conservation issues that brought him to Lake Champlain where

he was speaking then to the Vermont Fish and Game Commission

ion Isle LaMotte (this is well detailed in Douglas Brinkley's superb

2009 biography of Theodore Roosevelt, The Wilderness Warrior).

Many will recall that McKinley's condition improved over the next

few days and the vice-president's family retired to the

Adirondacks-near the town of Newcomb--where an ascent of Mt.

Marcy, the tallest mountain in New York State, was planned.

The ascent on September 12th was successful; McKinley's battle

for life was not. TR recalled in his autobiography that late that

afternoon a telegram was delivered to the party now ready to

descend, informing the vice-president that the president's

condition had deteriorated- followed shortly thereafter by

another that McKinley was dying and urging his return to Buffalo.

The 35-mile buckboard trip southeast to North Creek is now

legendary as is the news Roosevelt received at the train station of

McKinley's death three hours prior to his arrival at the train

station.

What strikes me is the coincidence of events on September 12th.

Roosevelt had achieved a personal goal by ascending Mt. Marcy

and viewing lands recently protected through the 1885

establishment of the Forest Preserve and-in 1892-Adirondack

Park. As a former Governor of New York, TR knew that the 2.5

million acre Forest Preserve had been further protected

constitutionally in 1895 by the "Forever Wild" provisions.

Unknown to him was a gathering that very same morning on

Mount Desert Island that realized a personal and complementary

Page I 3

goal of the president of the University from which Roosevelt had

graduated in 1880. There is an amusing tale of TR being part of a

committee of students who went to the offices of Harvard's chief

executive. "Overwhelmed, TR stammered forth an inverted

introduction. 'Mr. Eliot, I am President Roosevelt.' Ironically, this

would become true. (Donald G. Wilhelm. Theodore Roosevelt as

an Undergraduate. Boston: J.W. Luce & Co., 1910).

But in 1901 Harvard University president Charles William Eliot

was revered as the most influential figure in the history of

American higher education. He was about to begin his thirty-

second year in that role. Classes had not yet begun in Cambridge,

and Eliot's traditional Downeast Maine summer was drawing to a

close. His eldest son, landscape architect Charles Eliot, had

recently died at 37 years of age of spinal meningitis- and his

father was completing a massive 700-page biography of his son

which included his conservation plans and publications, much an

outgrowth of his work with partner Frederick Law Olmsted. But on

this day in early September, Charles W. Eliot was putting his

signature on a document in Bar Harbor that incorporated the

Hancock County Trustees of Public Reservations, the offspring of

the world's first land trust which Charles Eliot had established in

Massachusetts in 1891, six years before his tragic death.

The senior Eliot had gathered together prominent seasonal and

permanent island residents who loved the wild charm of this

island first discovered by Samuel de Champlain in 1604-and felt

growing concern about the increase in private ownership that

might soon deprive the public of access to many of the island

beautiful mountains, scenic points of interest, valleys, and lakes.

These men owned private estates but were offended when they

and others could not move freely; and so they offered their land

and sought gifts from others for the purpose of preserving chosen

Page I 4

parts of the coastal scenery, securing for the future an important

natural part of human prosperity for generations to come. Within

fifteen years this county land trust would offer to the federal

government 5,000 acres as a gift to the nation, becoming the

first national park east of the Mississippi River. This expression of

public philanthropy-from a group of private citizens-- to advance

the national parks was the first of its kind at the federal level that

was initiated by an organization--the HCTPR (See "Philanthropy

and the National Parks." www.nps.gov/history/history/hisnps/NPS

History/philanthropy.HTM)

These two September 12th, 1901 events-one on a mountain top

in the Adirondacks and another at a seaside resort on the coast

of Maine-are both responses to the impact of 9th-century

industrialization and the political and cultural impact of great

wealth. Progressivism is the name of this reform movement. A

key pillar of Roosevelt's progressivism was the emerging

conservationist philosophy expressed itself first in the writings of

Vermonter George Perkins Marsh, New York surveyor Verplank

Colvin, Massachusetts landscaper Charles Eliot, and others. As

Roosevelt come down the slopes of Mt. Marcy, Eliot charged

another Harvard graduate, George B. Dorr, with the task of

turning public philanthropy away from its customary expression

through benefactions to museums, hospitals, and social

institutions-and toward the protection of our environment.

Known more for culture than conservation, Mount Desert would

lead New England into a new consciousness

Seven months later, Eliot invited to Harvard the new president of

the United States to accept a Doctor of Laws degree; and in turn

TR invited Eliot to the White House for a few days to see what

plans he had set in motion. What united the two was the

conviction-expressed by TR-that "the rights of the public to

Page I 5

natural resources outweigh private rights, and ought to be given

its first consideration." In the years that followed their

relationship deepened. As Eliot's personal secretary explained,

"among the public men with whom President Eliot had frequent

correspondence were two Presidents of the United States,

Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson." (Jerome D. Greene,

"CWE-Anecdotal Reminiscences," Cambridge Historical Society 33

[1950]). Indeed, the late Rev. Peter J. Gomes of Harvard reminds

us that it was TR who said that "I have never envied any man

more than President Eliot. "("The Preservation Legacy of Charles

William Eliot," 2007)

But you might ask, what does all of this have to do with the

creation of Acadia National Park? Let me first ask, will those of

you who have not visited the Park raise your hands? So, some

context is necessary.

MDI is situated in the Gulf of Maine, roughly 200 miles northeast

of Boston. Its 110 square miles of soaring landscapes are barely

detached from the indented Maine coastline. A short causeway

connects the two. Glaciation and the constant power of the

Atlantic Ocean produced the most prominent feature of the

island: a range of granite mountains extending across its

southern half.

Seen from above the eastern half of the isle is separated from the

western half by a five-mile-long, very deep inlet known as Somes

Sound. Warm summer sunshine envelopes the spruce-fir and

northern hardwood forests that lie beneath the rugged

prominence of Cadillac Mountain, the highest mountain on the

eastern seaboard between Newfoundland and Rio de Janeiro.

A mobile community of native American hunters, fishers, and

gatherers came seasonally to this area before Samuel de

Page 6

Champlain's arrival in 1604. Despite Old World attempts by the

French and English to colonize the area, as late as the beginning

of the 19th-century, Mount Desert remained remote and

inaccessible. Nature writers and artists in the first half of the 19th-

century generated popular interest in its dramatic scenic beauty

and with railroad expansion after the Civil War, affluent seasonal

visitors accustomed to the fineries of Newport and Saratoga

traveled north from Boston, Philadelphia, and New York.

Two prominent Boston families prove central to our story. Charles

and Mary Dorr began raising their family in Jamaica Plain, a

Boston suburb. Just prior to the onset of the Civil War this Boston

merchant purchased a new elite townhouse being built on

Commonwealth Avenue, a real estate benefit of filling in the Back

Bay. Several blocks east across the Boston Common resided the

Charles W. Eliot family. This son of the former Treasurer of

Harvard University and Mayor of Boston, C.W. was a chemistry

professor at MIT and Harvard College who would soon occupy-in

1869--the office of President of Harvard Unuiversiy.

Inspired by Mount Desert, both families began journeying there

and by 1880 each had summer homes erected, the Dorrs in Bar

Harbor and the Eliots ten miles southeast in Northeast Harbor.

Over the next two decades much of the shoreline and some

mountainsides were being developed, the common land being

privatized. By the beginning of the 20th-century, some summer

people-known as Rusticators-felt that the cherished landscape

was being lost. Harvard's president stepped forward and applied

the principles to the shores of Maine that had worked well in

Massachusetts. This (HCTPR) was the world's second land trust,

the first bei ng established a decade earlier by Dr. Eliot's son.

Now, through gift and purchase, the most admired raw lands of

Mount Desert would be set aside for permanent public use. This

Page I 7

was a first step in trying to preserve what had first attracted

those from away to the island, those "from away" who were also

in flight from a variety of misfortunes that increasingly afflicted

growing cities: unsightly housing, immigrant overcrowding,

sanitation threats, industrial processes and their attendant

wastes, and the oppressive heat of summer. Where might one

escape the restrictive impact of these infirmities?

The acknowledged "Father of Acadia National Park", George Bucknam

Dorr, was predictably lauded but few knew more than a few anecdotes

about his origins-and the same was true for Harvard president,

Charles W. Eliot. Frequently philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr. was

emphasized for his financing of carriage road expansion. I began to

suspect that while not many on Mount Desert knew much about the

Harvard Eliot, research at Cambridge might show that few Harvard

people knew much about the Mount Desert Eliot. It became clear that

my talents would best serve this special place through a thorough

analysis of the historical records. Could I uncover sufficient evidence to

demonstrate connections between the historically-rich experiences of

the founders off the island and their contributions on Mount Desert

Island to the founding and initial administration of the park?

Page I 8

While the recently published biography details my findings, tonight I

want to focus on the process that made writing about these

conservation giants so satisfying. My experience as a university

educator, managing editor of an Association of College and Research

Libraries serial publication, and academic library administrator were

assets for the research challenges ahead. What began in 2001 as an

inquiry into few seemingly unrelated questions, within a few years the

questions, methods, and findings were grouped thematically and public

talks and publications followed. By 2004 the depth and range of my

findings clearly indicated that a biography the park father and his

associates-including those engaged in establishing the National Park

Service-was required by the scholarship previously uncovered.

Interviews and archival research at repositories westward from Maine

to California-and eastward from North Carolina to the York

countryside in England-- yielded provocative findings even as I

misjudged my own timeline, thinking that publication would be far in

advance of the 1916 centennial of the establishment of the National

Park Service and Acadia National Park. Their establishment--within

Page I 9

seven weeks of one another-would be intertwined in my book.

Moreover, since conservation histories made light of Acadia National

Park, I had to conceptually situate the importance of this federalized

land trust movement within the history of New England conservation

history.

Dorr's unpublished correspondence with John D. Rockefeller, Jr. (1874-

1960) and his less restrained letters to and from Harvard president

C.W. Eliot (1834-1926) provided the key manuscript resources for this

study. There is a well-known descriptor for the three-fold union of

philanthropist Rockefeller, educator Eliot, and park creator Dorr: "The

Acadian Trimvirate." For it is only through their relationships with one

another that Acadia National Park came into being. The Sawtelle

Research Center at Acadia National Park, the National Archives, the

New England Historic and Genealogical Society, and the Massachusetts

Historical Society were the key archives for repeated visits researching

Dorr legacy; Harvard University Archives provided the bulk of

documentation for Dr. Eliot; and the Rockefeller Archive Center in

Tarrytown served the philanthropist handsomely. Supplementing this

Page I 10

institutional foundation, dozens of interviews with Rockefeller and Eliot

family members were undertaken as well as with others whose

thoughts would bear on the themes of this biography. This detective

work quite obviously was time-consuming, largely solitary, and

appeared at times as an endless enterprise.

But on a more elevated plane, Dorr's environmental legacy was a

tabula rasa, a blank slate. With one exception (e.g., Harvard

senior year forecasting note), none of his writings prior to his

fortieth year survive. He has been almost entirely ignored by

both academics and popularizers.

Dorr's memorabilia in a fragmented state went unprocessed and

subsequently ignored in the Bar Harbor Historical Society. No

graduate student had pursued Dorr as a subject worthy of a

completed thesis or dissertation. Only one interview was ever

undertaken; subsequently published in a little read serial, Maine

Highways, its author, B. Morton Havey, argued that "this man

[should] receive the fullest credit for his accomplishment.

However, Mr. Dorr throughout the interview did "not feel it

necessary or expedient to associate his own personality with

Acadia National Park." Dorr was highly adept at "courteously, but

efficiently, [avoiding] my direct questioning." Only as recently as

Page I 11

the 1990's did NPS historian Richard Quin publish an account of

Dorr's contributions to the Park (i.e. ANP Roads and Bridges,

1994-1997).

Cynics might explain this shallowness of research by claiming that

Dorr's achievements did not warrant more than what had been

entered into the published records. A few days, however, in

College Park Maryland at the National Archives corrected this

misperception. Tens of thousands of NPS official documents

relative to Acadia National Park detail the park's first three

decades, place Dorr's achievements within the context of NPS

policies and the larger political climate, and offer abundant

evidence of the conservation principles guiding Dorr's

governance.

Most fascinating are hundreds of monthly superintendent reports

in the National Archives submitted by Dorr to the NPS, each

containing insights into Dorr's intentions and behavior-exactly

what I had been looking for! Yet as with all research one

examines primary resource materials in light of what one knows

at that given moment. I neglected to look in sufficient depth at

the documentation of Dorr's superiors spanning three decades.

Similarly, when examining the papers of Dorr's maternal

grandfather at the Massachusetts Historical Society I only later

Page I 12

realized that I had narrowed by research to too limited a number

of years in his grandfather's life. This awareness comes months

or years later as the breadth of one's knowledge has expanded-

and sometimes too late to return to the originals.

My experience as a philosopher teaching environmental ethics

certainly brought me in touch with major thinkers. What I found

lacking was attention to the conservation efforts of New

Englanders-with only passing references to David Thoreau and

George Perkins Marsh who argued that "Man is everywhere a

disturbing agent. Wherever he plants his foot, the harmonies of

natured are turned to discord."

Historical facts that I uncovered in archival records contributed to

my appreciation for the distinctive New England approach to land

conservation, one unlike other regions of America. These themes-

-SO well-articulated by Charles H.W. Foster-- are (1) a

commitment to self-determination, (2) emphasis on innovation,

(3) a reliance on individual leadership "as a first resort," (4) a

strong investment in place, (5) a long history of civic

engagement, and lastly, (6) deep ethical concerns for the

environment (20th-Century New England Land Conservation, HUP,

2009).

Page I 13

As my writing progressed I was repeatedly impressed by new

online references that would have made my inquiry more efficient

and accurate if only they had been available earlier in the process

(e.g., Massachusetts Horticultural Society Proceedings). Quite

unlike the Gilded Age of Mr. Dorr, we live in a culture where

nearly everything is conveniently delivered to meet our needs.

There seems to be a telecommunication solution for any

commodity that is sought. However, most documents and images

that I required would not be transmitted to me electronically. I

was required to visit the archival repository to access the

resource. Why? The risk of loss of originals was too great, the

materials too fragile. To access books, photographs, postcards,

deeds, sound recordings, moving images, and other cultural

artifacts requires legwork--not keystrokes-- to travel to where

these "treasures" are stored. Often it is only through personal

contact and the cultivation of trust that the existence of an

intellectual resource is disclosed. Briefly, two examples come to

mind, opportunities to dramatically add to the historical record

that occurred after I had completed the Creating Acadia National

Park.

We all know that it is important to honor founders of worthwhile

institutions and enterprises, and to remember them not for their

sakes but for our sakes, and not for the sake of the past alone

but for the sake of the future. Men like Dorr, Eliot, and

Rockefeller were intensely concerned about the future of the

place that each discovered in his own unique way. They expended

vast amounts of energy to originate, develop, and perfect

strategies to conserve what Eliot articulated as the durable values

of life. "The things that last, that are not creatures of fashion, the

things that do not come and go; for out of this conviction derived

the principle of conservation.

Page I 14

Moreover, Eliot shared with the other founders that belief he so

earnestly fostered at Harvard College, the notion of the public

good; that the durability of the good implies that everyone should

benefit from it, not only the wealthy; these three men, each

derivative of an elitist heritage, became convinced that something

of beauty should be preserved for the public and not for the

privileged few. Their words and actions on conservation were

democratic to the core. And each had very specific interests in

landscape, in reflecting seriously on what lay beneath our feet

and was almost universally taken for granted-and in that

unreflective process too often dismissed as unworthy of design.

In the end, I hope that my book reveals what can be

accomplished when three men align with a common-and

expansive-vision and take the necessary steps to achieve it.

Others might see on this island a collection of small farms, a vast

untracked wilderness, waterways, and undeveloped resources-

where they saw an environment for the national and public good.

Collectively they were able to persuade others not only to invest

in their vision but to take the unprecedented step to engage the

federal government in protecting it. One hopes that this is a

generational lesson for all of us.

8/26/2020

Xfinity Connect Re_editorial_wnyheritage_org Printout

RONALD EPP

8/26/2020 11:06 AM

Re: editorial@wnyheritage.org

To Douglas DeCroix

Dear Mr. DeCroix,

Thank you for responding to my request to be added to your newsletter

distribution list.

It occurred to me that you might have an interest in an article that I am

revising. The environmental significance of Vice President Theodore

Roosevelt's descent from Mount Marcy on September 12, 1901 has

been well documented. What has not been previously joined with this

fact is that on that same date a commitment was made in a Bar Harbor

law office that dovetailed with the inception of the Roosevelt

conservation agenda.

At the same time, Harvard University president Charles W. Eliot and a

dozen Mount Desert Island neighbors signed the Hancock County

Trustees of Public Reservations incorporation papers. In forming an

organization to conserve for public use the unique natural beauties of

this Downeast island they created the world's second land trust--the first

being established a decade earlier in Massachusetts by Eliot's son. As

President Roosevelt championed a vast conservation movement, the

Trustees assembled private lands that became Acadia National Park.

This temporal intersection of different Progressive strategies was first

presented in a 2016 public address in Buffalo at the Theodore Roosevelt

Inaugural Site.

If you have interest in publishing this roughly 2,000-word article, please

contact me. You can find additional professional information about me

by googling "Epp & Acadia."

Ronald H. Epp, Ph.D.

7 Peachtree Terrace

https://connect.xfinity.com/appsuite/v=7.10.3-6.20200722.052513/print.html?print_1598454413968

1/3

6/10/2020

"Writing About Conservation Giants" I inSITE I Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural Site

Collections (26)

Community (28)

General (54)

Issues of the Day, Issues of Today (22)

Speaker Recap (42)

Recent Posts

"Writing About Conservation Giants"

Tuesday, October 18th, 2016

1

hote

I feel like I should start this post with a disclaimer: Acadia National Park, on

Maine's Mount Desert Island, is one of my all-time favorite places, ever. Which

explains why I was SO excited when Ronald Epp (who recently finished the

first booklenath hiography of park founder George Bucknam Dorr) contacted me

6/10/2020

"Writing About Conservation Giants" I inSITE Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural Site

to find out if the TR Site would be interested in having him speak about this

unsung hero of the American environmental movement and the pioneering role he

played in the development of a unique conservation model. Needless to say, when

Dr. Epp arrived last month and began weaving a complex story of philanthropy and

environmental conservation, aided and inspired by Harvard connections, I was

fascinated.

Dr. Epp began his remarks by pointing out that September 14th, 1901 was an

important day for the environmental conservation movement on at least two levels.

That was the day that Theodore Roosevelt -- the first and arguably the most

enthusiastic president to put conservation on the national agenda -- took the oath of

office. On the same day, a small group of men met on Maine's Mount Desert

Island and took the first steps in the lengthy process that ultimately led to the

creation of Acadia National Park.

It should probably be noted that Maine and Mount Desert Island were both familiar

to the new president. While he was an undergraduate at Harvard, TR spent time in

Maine -- an interlude that some scholars suggest was critical to his appreciation of

the natural world and his evolution as a conservationist. After graduation in 1880,

Roosevelt returned to Maine and spent time on Mount Desert Island. TR hiked

Mount Desert's mountains, sailed its waters, and rode horseback on its trails. The

oceanside setting also provided inspiration as he worked on his first book, The

Naval War of 1812.

The men who met on Mount Desert Island twenty years later, as Roosevelt was

being inaugurated in Buffalo, were brought together by Charles W. Eliot. Perhaps

best-known for his role as president of Harvard, Eliot's family had long-standing

connections to Mount Desert Island and his oldest son was a pioneering landscape

architect. In the last years of the nineteenth century, Eliot watched with concern as

development began interfering with Mount Desert Island's landscapes and public

access to that land was being restricted by new owners. Thus, Eliot arranged a

series of late summer meetings in 1901 that led to the formation of a land trust

known as the Hancock County Trustees of Public Reservations (HCTPR). The

handful of men who formed HCTPR sought "to acquire, by gift or purchase, land

deemed important for its scenic or historic value - and then manage it for public

use."

Working closely with Eliot and serving as HCTPR's first Vice President was

George Bucknam Dorr, another "Harvard man" whose familial connection to

Mount Desert Island began in 1868. Dorr gave life to HCTPR's ambitious goals.

In fact, it was largely due to Dorr's determination and energy that HCPTR was

able to acquire the 5,000 acres that became the nucleus of what is now Acadia

National Park. Dorr not only worked with landowners to encourage donations, but

also later cultivated a crucial relationship with John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

6/10/2020

"Writing About Conservation Giants" I inSITE I Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural Site

Despite HCTPR's successes, Dorr and Eliot were concerned -- due to the political

climate in the state -- that the land trust would ultimately be unable to protect the

lands it had acquired. Because federal protections would be stronger, a plan was

hatched to offer the amassed property to the federal government. Dr. Epp

explained that this idea was entirely new and considered somewhat suspect at first.

In the past, national parks and monuments (think Yosemite or Devil's Tower) were

carved out of land that was already owned by the federal government. When

HCTPR approached the Department of Interior with their proposal, lawmakers and

others had a hard time understanding why anyone would want to give anything to

the federal government. George Dorr took on the daunting task of going to

Washington and lobbying for the unorthodox proposal. Thanks largely to Dorr's

persistence, Woodrow Wilson declared the donated land a national monument on

July 8th, 1916 (a mere seven weeks before the National Park Service was formally

established). Not quite three years later, it was elevated to national park status and

became the first national park east of the Mississippi River. George Dorr served as

the park's first superintendent and continued to shape its course for the next

quarter-century.

Dr. Epp concluded his remarks by reflecting on the conservation ethic -- created

and promoted by the likes of George B. Dorr, Charles Eliot, and John D.

Rockefeller, Jr. -- that ultimately allowed for the creation of Acadia National Park.

In addressing a unique set of circumstances, these men drew upon their distinctly

New England roots and incorporated values such as: self-determination;

innovation; a reliance on individual leadership; a strong investment in place; civic

engagement; and, perhaps most important, an ethical concern for the environment

and future generations.

-- Lenora M. Henson, Curator / Director Public Programming

Speaker Nite is part of the TR Site's regular Tuesday evening programming, which

is made possible with support from M&T Bank.

Tags:

Back to Blog

Site Map

Home

Learn

Explore

THEODORE

ROOSEVELT

INAUGURAL

NATIONAL

HISTORIC SITE

16 March 2016

641 Delaware Avenue

Buffalo, New York 14202

Ronald H. Epp, Ph.D.

716 884 0095

532 Sassafras Dr.

716 884 0330 fax

Lebanon, PA 17042

www.trsite.org

RE: "Writing about Conservation Giants: America's First National Park East of the

Mississippi" / Tuesday, September 27, 2016 6-8pm

Dear Dr. Epp:

This letter formalizes our invitation to speak at the Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural

National Historic Site (TR Site) at 6:00pm on Tuesday, September 27, 2016, as part of our

2016 speaker series.

As mentioned in my earlier email message, we are able to offer you an honorarium of

$100.00, which will be delivered at the conclusion of your presentation.

Please fill out, sign and return one copy of the enclosed Speaker Agreement Form as

confirmation of your agreement to speak. A return envelope has been provided for your

convenience.

If you have any questions or concerns regarding your presentation or the terms of the

Agreement, please contact me as soon as possible. I will serve as your primary contact

here at the TR Site, and can be reached by telephone at: (716) 884-0095, or via e-mail at:

Lenora_Henson@partner.nps.gov

We look forward to welcoming you to the Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National

Historic Site.

Sincerely,

LenoneMMenso

Lenora M. Henson

Curator / Director of Public Programming

Bringing Legend Life

THEODORE

ROOSEVELT

INAUGURAL

Speaker Agreement

NATIONAL

HISTORIC SITE

Speaker Name: Ronald H. Epp, Ph.D.

Presentation Date/Time: Tuesday, September 27, 2016 / 6:00pm

641 Delaware Avenue

Presentation Title: "Writing about Conservation Giants: America's First

Buffalo, New York 14202

National Park East of the Mississippi"

716 884 0095

716 884 0330 fax

www.trsite.org

Presentations at the TR Site are generally about 45 minutes long and are

followed by discussion/Q&A, as well as light refreshments.

A/V Requirements:

I

will

will not be using a visual presentation (e.g., PowerPoint or Keynote).

The TR Site generally provides speakers with a lectern, microphone, laptop, wireless connection,

projector, and screen. Please check here if you prefer to bring/use your own laptop

I

will

will not be using embedded audio and/or video clips in my presentation.

I

will

will not require additional a/v equipment for my presentation. lapel

MIC .

As necessary, someone from the TR Site will contact you to discuss your additional a/v needs.

Travel/Accommodations (out of -town speakers only)

The TR Site will pay for round trip transportation (e.g., car rental/fuel or mileage or

airfare) up to $ [amount]. Mileage (if applicable) will be reimbursed at the rate set

by the federal government.

I will make my own travel arrangements and submit receipts to the TR Site for

reimbursement within 14 days of my presentation.

I prefer that the TR Site handle my travel arrangements and agree to provide

any information that the TR Site needs to do so upon request.

The TR Site will arrange for one (1) night's accommodations at a near by hotel, on the

evening of my presentation.

Honorarium

The TR Site will pay an honorarium in the amount of $ 100.00 , to be delivered at

the conclusion of my presentation.

Permissions

I authorize the TR Site to use my name, photo, and biographical data in connection

with the promotion of my presentation.

BringingaLegendtoLife

(Continued on reverse)

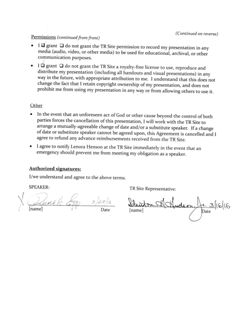

Permissions (continued from front)

I

grant

do not grant the TR Site permission to record my presentation in any

media (audio, video, or other media) to be used for educational, archival, or other

communication purposes.

I

grant

do not grant the TR Site a royalty-free license to use, reproduce and

distribute my presentation (including all handouts and visual presentations) in any

way in the future, with appropriate attribution to me. I understand that this does not

change the fact that I retain copyright ownership of my presentation, and does not

prohibit me from using my presentation in any way or from allowing others to use it.

Other

In the event that an unforeseen act of God or other cause beyond the control of both

parties forces the cancellation of this presentation, I will work with the TR Site to

arrange a mutually-agreeable change of date and/or a substitute speaker. If a change

of date or substitute speaker cannot be agreed upon, this Agreement is cancelled and I

agree to refund any advance reimbursements received from the TR Site.

I agree to notify Lenora Henson at the TR Site immediately in the event that an

emergency should prevent me from meeting my obligation as a speaker.

Authorized signatures:

I/we understand and agree to the above terms.

SPEAKER:

TR Site Representative:

X Don't Epp

3/27/16

[name]

Date

[name] Date

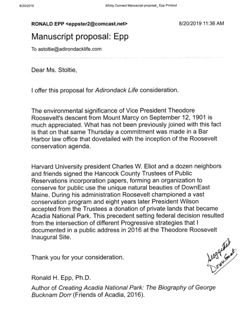

8/20/2019

Xfinity Connect Manuscript proposal_Ep Printout

RONALD EPP

8/20/2019 11:36 AM

Manuscript proposal: Epp

To astoltie@adirondacklife.com

Dear Ms. Stoltie,

I offer this proposal for Adirondack Life consideration.

The environmental significance of Vice President Theodore

Roosevelt's descent from Mount Marcy on September 12, 1901 is

much appreciated. What has not been previously joined with this fact

is that on that same Thursday a commitment was made in a Bar

Harbor law office that dovetailed with the inception of the Roosevelt

conservation agenda.

Harvard University president Charles W. Eliot and a dozen neighbors

and friends signed the Hancock County Trustees of Public

Reservations incorporation papers, forming an organization to

conserve for public use the unique natural beauties of DownEast

Maine. During his administration Roosevelt championed a vast

conservation program and eight years later President Wilson

accepted from the Trustees a donation of private lands that became

Acadia National Park. This precedent setting federal decision resulted

from the intersection of different Progressive strategies that I

documented in a public address in 2016 at the Theodore Roosevelt

Inaugural Site.

Thank you for your consideration.

Love

Ronald H. Epp, Ph.D.

Author of Creating Acadia National Park: The Biography of George

Bucknam Dorr (Friends of Acadia, 2016).

Viewer Controls

Toggle Page Navigator

P

Toggle Hotspots

H

Toggle Readerview

V

Toggle Search Bar

S

Toggle Viewer Info

I

Toggle Metadata

M

Zoom-In

+

Zoom-Out

-

Re-Center Document

Previous Page

←

Next Page

→

[Series IX] Theodore Roosevelt and the Mt Desert Triumvirate (Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site, Buffalo NY)

| Page | Type | Title | Date | Source | Other notes |

| 2 | Webpage | About: Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural Site | 10/03/2021 | https://www.trsite.org/about | - |

| 3-16 | Lecture | Theodore Roosevelt & the Mount Desert Triumvirate | 09/17/2016 | Ronald Epp | - |

| 17 | Email from Ronald Epp to Douglas DeCroix: Re: editorial@wnyheritage.org | 08/26/2020 | Ronald Epp | Annotated by Ronald Epp | |

| 18-20 | Web Page | "Writing About Conservation Giants" : Lenora Henson | 06/10/2020 | Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural Site: inSITE | - |

| 21 | Letter | Letter from Lenora Henson to Ronald Epp: RE: "Writing about Conservation Giants: America's First National Park East of the Mississippi" / Tuesday, September 27, zot.6 / 6-8pm | 03/16/2016 | Lenora Henson | - |

| 22-23 | Contract | Speaker Agreement: Ronald Epp: Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural Site | 03/16/2016 | Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site | Annotated by Ronald Epp |

| 24 | Email from Ronald Epp to A. Stoltie: Manuscript Proposal: Epp | 08/20/2019 | Ronald Epp | Annotated by Ronald Epp |