From collection Creating Acadia National Park: The George B. Dorr Research Archive of Ronald H. Epp

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Search

results in pages

Metadata

[Series III] The Mount

The Mount

THE MOUNT

Estate & Gardens

June 12, 2006

Ronald and Elizabeth Epp

47 Pond View Drive

Merrimack, NH 03054

Ron

Dear Ronald and Elizabeth,

We at Edith Wharton Restoration would like to thank you for participating in the first

ever garden conference at The Mount, Edith Wharton and the American Garden. The

enthusiastic, inspired group of attendees made the soggy weekend truly shine with ideas

and energy.

We hope this conference will be the first of many as we begin to establish The Mount as

a center for original scholarship. To echo Hugh Hardy's eloquent call for action: just as

Edith Wharton was a forward-thinking woman of ideas, so, too, must we continue in our

search to find new and fresh ways of keeping The Mount relevant and vigorous in the

years ahead.

Your experience at The Mount as both a visitor and a conference participant is important

to us. Please take a moment to fill out the enclosed questionnaire and return it in the

addressed, stamped envelope. We greatly appreciate your comments, and we hope to see

you soon at a future conference at The Mount.

Sincerely,

Betsy

Betsy Anderson

Garden Historian

Enclosures

www.Edietwharton.org

2 Plunkett Street

Box 974

Lenox, MA 01240-0974

phone 413-637-1899 fax 413-637-0619 email admin@edithwharton.org

Edith Wharton and the American Garden.

Lenox, MA The about Press, 2009.

CONTENTS

Foreword

ix

Acknowledgments

X

Introduction

xi

A Genius for Place: American Landscapes of the Country Place Era

Robin Karson

3

Edith Wharton: An Encounter with the Berkshires

Honey Sharp

25

Sensations of the Unexpected: The Untamed Forms and Disciplined

Lines of Edith Wharton's American Villa

David H. Bennett

41

Opposites Attract: The Garden Art of Charles Platt, Maxfield

Parrish, and Edith Wharton

Rebecca Warren Davidson

61

Wild Gardens and Pathways at The Mount: George B. Dorr and the

Mount Desert Island Influence

Ronald H. Epp

75

Circles of Influence: Edith Wharton and the Gardens of the

Anglo-American Expatriate Community

Ethne Clarke

89

Edith Wharton's Plants: Her Influence on the Riviera and in

Southern California

Diane Kostial McGuire

97

The Romantic and the Practical: Edith Wharton and Beatrix

Farrand as Gardeners and Garden Writers

Eleanor Dwight

107

Edith Wharton's Literary Garden

Betsy Anderson

125

Edith Wharton and the Cultivation of Voice, Authority,

Passion, and Privilege

Paula Panich

141

Edith Wharton, The Mount, and the Future

Hugh Hardy

147

Contributors

161

WILD GARDENS AND

PATHWAYS AT THE MOUNT:

GEORGE B. DORR AND THE

MOUNT DESERT ISLAND INFLUENCE

RONALD H. Epp

T

he Beinecke Library at Yale University contains a handful of Edith Wharton letters to pioneer

conservationist and horticulturist George Bucknam Dorr (1853-1944). This correspondence

is

commonly passed over by scholars. ² The ten Wharton letters written between 1902 and 1907 are

unremarkable when isolated from the richly diverse social context of the Gilded Age. They are

remarkable if attention is given to previously unrecognized interactions between the Dorr and Jones

families that began twenty years earlier in Bar Harbor, Maine, where Wharton's brother and sister-in-

law Frederic and Mary Jones summered. Furthermore, the connection of the Dorr family with Lenox,

Massachusetts-site of Wharton's own summer house-tracks back another fifty years to the era of

Catharine Sedgwick and Fanny Kemble. 3

The Wharton correspondence to Dorr ranges in length from a few sentences to several

hundred words. All but two letters were written during an eighteen-month period between September

1904 and February 1906. Some specialists might describe them as technical, narrowly focused

on Wharton's solicitations of Dorr's horticultural expertise. Yet this is not inconsequential, for

The Mount's garden historian, Betsy Anderson, indicated on a recent site inspection that there is

little evidence of Wharton's use of expert landscaping advice outside her family. Unfortunately, no

correspondence from Dorr to Wharton has survived.

There has been no inquiry into the connection between the location and naming of gardens

and paths at The Mount and Dorr's professional and cultural life on Mount Desert Island. What

character traits did he bring to the table in relating to Wharton that encouraged her to invite him

repeatedly to her home? What motivated her to involve this little-known Boston Brahmin in her wild

gardening? Wharton's letters to Dorr refer frequently to a path at The Mount named for him. Why

would she choose to honor him in this way? It is intriguing that Dorr left us no documentation of his

relationship with her, especially since his advice to Wharton is the only recorded case of his engaging in

a horticultural consultancy removed from Mount Desert Island. Many of these questions will never be

resolved since, following his death in 1944, the National Park Service disposed of most of the contents

of the Bar Harbor estate that he had gifted to the government.

However, in 2006 new primary evidence for the Dorr-Jones family relationship came to light.

Both families developed their Bar Harbor properties in the 1880s, and their social interactions are

75

RONALD H. EPP

recorded in a guest book kept by the Dorr family at their cottage called Oldfarm. For more than sixty

years the Bar Harbor Historical Society Museum displayed this document, yet preservation restrictions

prohibited scholarly access until 2004 when the entries were inventoried as part of my biographical

research on Dorr as the founder and first superintendent of Acadia National Park (1916-44).

The garden concepts of the park founder were framed by generations of family gardening

in Salem, Massachusetts, prior to the family's relocation to Boston following the Revolutionary

War. The importance of household gardens is repeatedly expressed in the surviving manuscripts

of Dorr's maternal grandfather, Harvard College treasurer and renowned banker Thomas Wren

Ward (1786-1858).4 His son Samuel Gray Ward (1817-1907), frequently identified as the first

Lenox cottager, "had a passion for gardening and manfully ploughed and planted in the beautiful

surroundings of Lenox."S

The Maine coastline dominated Dorr's later life, Boston and the European continent were

of this his middle middle years, but the countryside in Lenox and outside Boston shaped his childhood.

While the family townhouse adjacent to Boston Common afforded little opportunity for extensive

gardening, young George spent summers in country homes in Jamaica Plain, Canton, Nahant, and

Lenox where his interests in gardening and birding were encouraged and the nearby woods afforded

him pathways for exploration.

At that time many Boston Brahmins looked beyond Newport and Nahant for scenic

stimulation and recreational opportunities. Mount Desert Island had been celebrated by Hudson River

School artists prior to the Civil War, and increasingly word spread about the beauty of Frenchman Bay,

Figure 1. Compass Harbor, Frenchman Bay, Mount Desert Island. Photograph courtesy

of the National Park Service, Acadia National Park's William Otis Sawtelle Collections

and Research Center.

76

WILD GARDENS AND PATHWAYS AT THE MOUNT

Figure 2. George B. Dorr, Harvard College, 1874. Photograph courtesy of the

National Park Service, Acadia National Park's William Otis Sawtelle Collections

and Research Center.

the uniquely colored mountains towering over the deepest fiord in North America, and the primeval

old-growth forests. The Dorrs were captivated and in 1868 purchased more than a hundred acres of Bar

Harbor woodland fronting the bay (figure 1).6

At Harvard College Dorr received no specialized instruction in botany. Like his elder stepcousin

Charles Sprague Sargent Dorr possessed exceptional botanical aptitude derived from an amalgam of

family values, wide reading, and extensive field experience-a not uncommon lineage at the time.7

He also acknowledged the "unsurpassed" influence of landscape designer Andrew Jackson Downing,

crediting to him the "foresight

[for] our present American system of broad free municipal parks"

incorporating picturesque precepts that Dorr eventually applied on Mount Desert Island. 8

After Dorr's graduation from Harvard College in 1874 (figure 2), he and his parents traveled

abroad for several years, where much of their activity centered on visits to a great variety of European

gardens. More than a dozen essays written by Dorr in his later life detail these visits to both modest and

grand European gardens; not content with a mere tourist's acquaintance, Dorr's scholarly curiosity led

him to pursue their historical origins and development. In those early years Dorr was most impressed

with the simple gardens surrounding English cottages. The reason he offers for this preference is

unambiguous and yet surprising for someone of his class: their modest efforts brought beauty into the

monotony of their lives.

Dorr describes the specific location that the family chose in 1878 for their new Mount Desert

home, "[a] broad, flat top of an old sea-cliff, facing north to

the long reach of Upper Frenchman

Bay" (figure 3).° Few properties on the island offered such superb views, and the considerable water

77

WILD GARDENS AND PATHWAYS AT THE MOUNT

frontage was cloaked in dense woods. Dorr repeatedly insists that the gardens at Oldfarm, initially

developed by his mother, would not have come into being were it not for the effect on the family of

the beautiful old English gardens and the remnants of the old English homes they visited. It is Dorr's

sincerest conviction that the Oldfarm gardens, more than anything else, led him step by step to the

founding of Acadia National Park.

Mary Gray Ward Dorr (1820-1901) and her son modified the landscape, acquired local plant

stock, and transplanted their hardy Massachusetts flowering shrubs and herbaceous plants to Mount

Desert Island (figure 4). They were intent on experimenting to determine whether their relocated

garden would adapt to local conditions. In 1883 Edith Wharton's brother Frederic Jones and his wife,

Mary, purchased their original two-acre Bar Harbor property, Reef Point. The Jones family relationship

with the Dorrs likely dates to this time when Edith Newbold Jones (later Wharton) joined her brother,

sister-in-law, and niece, Beatrix, in Bar Harbor, rented a cottage, "mealed" at the Hotel des Isles, and

explored the coast and mountainous terrain. Teddy Wharton was also in Bar Harbor that summer, it is

probable that he and Dorr interacted since they had been Harvard College classmates ten years earlier.

Figure 4. Entrance to Oldfarm from the southwest drive, Bar Harbor, Maine.

Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service, Acadia National Park's William

Otis Sawtelle Collections and Research Center.

79

RONALD H. EPP

The Dorr and Jones family exercised leadership as charter members in the Bar Harbor Village

Improvement Association. 10 It is not until July 1891, however, that we have confirmation of a certain

level of "intimacy" between the families. That July Mary Cadwalader Jones pens a poem beside her

signature in the Oldfarm guest book; twenty-year-old daughter Beatrix is a guest-perhaps only for

dinner-the following September. Their most notable shared friends are the James brothers, Henry and

William. For weeks at a time William, the famed Harvard philosophy professor, and his wife, Alice, are

Oldfarm guests. 11

The social interaction between Oldfarm and Reef Point likely had an impact on the

professional development of young Beatrix Jones, who would become the eminent landscape architect

Beatrix Farrand. Although Dorr's influence on Farrand lies beyond the scope of this paper, the depth

of Farrand's appreciation of Dorr is reflected in the 1917 article she wrote for Scribner's Magazine on

"The National Park on Mount Desert Island." Here she refers to his decades of "unswerving and far-

sighted devotion to the ultimate usefulness of the island" and that every Mount Desert Island visitor

"owes a large share of his enjoyment to the clear vision, the wise development, and the self-sacrificing

enthusiasm of [George Dorr]. 12

GARDENS-PERSONAL - AND PROFESSIONAL

We know that a rose garden lay to the northeast of Dorr's Oldfarm home screened by a rock

ridge to the east that ran down to Compass Harbor. Cedar hedges enclosed garden paths-bordered

by phlox, peonies, false Solomon's seal, gladioli, and golden lilies-that led visitors to huge vegetable

gardens intermingled with fruit trees, all maintained for at least half a century. The local paper

described the property as "one of the most attractive of the showplaces of the village," praising its

wood-encircled, old-fashioned flower gardens as sufficiently diversified to "fit the taste of any flower

lover." 13 What remains undocumented are the planting designs; the role of indigenous species; whether

plantings enhanced scenic views; which species were native to the property; or whether artificial devices

(for example, lighting or sculpture) were design elements-all matters that may have influenced his

advice to Wharton.

Dorr was not content to restrict himself to family gardening. The famous Boston flower shows,

the woody plant experimentation at the Arnold Arboretum, and Sargent's Garden and Forest motivated

him to start a business that reflected not only his values but those of his parents and grandparents. He

established the first island nursery in 1896, converting more than thirty acres of adjacent Oldfarm

property into the Mount Desert Nurseries. Although both Dorr and Sargent lacked formal instruction

in the botanical sciences, they combined the horticulturist's interest in cultivated species with the

botanist's research focus on wild plants, a "relatively rare combination" for the era. 14

By 1901 the Bar Harbor Record referred to the "immense scale on which this business is

conducted," with plant stock shipped to the West Coast as well as meeting the demands of the

burgeoning

hotel

and cottage communities.¹5 Wharton surely heard about this expansion from her

niece since Farrand's Mount Desert commissions utilized Dorr's plant stock. In subsequent years,

greenhouse expansion and reconsideration of the purposes of a nursery anticipated what we today

refer to as a garden center. The plans included a forty-eight-foot-long nursery gallery showcasing

80

WILD GARDENS AND PATHWAYS AT THE MOUNT

Dorr's "unrivalled collection of photographs of the Wild National Parks of the West and a great many

photographs of flowers. Unfortunately, the catastrophic island forest fire of 1947 laid ruin to scores

of businesses-including Dorr's nurseries-and the cottage culture.

WHARTON'S LETTERS TO DORR

As we focus on the era of Wharton's letters to Dorr, the year 1901 proves particularly

significant. Both lost their mother that year; the Whartons purchased farmland in Lenox to experience

what she described as "the joys of six or seven months a year among fields and woods of my own"; ¹

Wharton's early short story collection Crucial Instances was published; and Dorr became the central

figure in an organized effort to conserve Mount Desert Island. Harvard University President Charles W.

Eliot gathered together conservation-minded island residents to establish the Hancock County Trustees

of Public Reservations, a group that included George W. Vanderbilt. 18 Dorr was both the Trustees'

organizational executive and the field agent who was almost singularly responsible for the acquisition

of more than five thousand acres of land that would be accepted by the federal government in 1916, a

precedent-setting effort recounted in Dorr's The Story of Acadia National Park19

Dorr's involvement in the development of The Mount gardens may have had as much to

do with his Bar Harbor and Boston social interactions as with his horticultural reputation. When

the timeline of Dorr's and Wharton's lives are compared, we see that Wharton's first known visit to

George W. Vanderbilt's Biltmore estate in Asheville, North Carolina (November 26, 1902) is the day

before Dorr arrived. 20 Vanderbilt was a fellow trustees incorporator whose Point d'Acadie estate was a

short walk from Oldfarm; he was also a friend of Dorr's who shared a command and appreciation of

languages and a serious interest in woodlands. Whether the Vanderbilts arranged these visits to overlap

we cannot say.

Less than a month after her departure from Asheville, Wharton writes to Dorr-the first of the

ten surviving letters to him in the Beinecke Library-expressing the hope that they might be able to

accept his dinner invitation in Boston.21

In the summer of 1904 Dorr planned a backpacking trip to the largely unexplored Sierra

Nevada Mountains south of Yosemite. En route he stopped at The Mount, as indicated by a letter

Wharton wrote him on September 3 that begins the most fruitful period of their correspondence. She

has found one of his books on the terrace after his departure (which was forwarded to Boston), and

she thanks him for his help with landscape design problems. Wharton flatters him by stating that he

left behind "so many fruitful ideas that I often feel you are not really gone, and must be somewhere

about, ready to answer the new questions." Moreover, she informs him that "your path is finished,

and the task of planting its borders now confronts me; & we are just about to attack the laying out of

the path from the flower-garden to the little valley which is to be my future wild garden." Referring to

Dorr's trip West, she is hopeful that "you may be able to spare us a day or two on your return" when

the autumn work will be nearly over and future plans can be discussed unless "my pigmy planting will

quite vanish from your mind among the giant boles of the redwoods!"

In late 1994 Wharton writes Dorr (October 29) that she is delighted at the prospect of

another visit with him since she and Teddy both are "so interested to hear about your explorations."

81

RONALD H. EPP

A month later (November 29), she acknowledges his October letter but fears that her letter to him may

have gone astray, and regrets that a November visit seems unlikely since they are snowed under "and

therefore of no interest from the landscape gardener's standpoint." Nonetheless, she hopes for a visit in

1905 when "[you could] see how far I was able to carry out your advice, and tell me what to do next."

Dorr's final visit to Biltmore (October 18, 1905) precedes the Whartons' Christmas visit,

a festive occasion when jasmine, honeysuckle, and laurel set the tone for a seasonal fete for the 350

people who lived and worked on the estate. Two days after Christmas she writes Dorr from the

Biltmore house stating that she has "never received an invitation more comprehensively hospitable than

yours," regarding his proposal for a January 1906 visit to his Commonwealth Avenue home in Boston,

where she looks forward to "good talks on horticulture, free-will and predestination." That the later

two topics are mentioned should startle no one familiar with the Dorr and James family associations

with psychical research and philosophical inquiry. While Dorr was on Wharton's mind, however, he

was much occupied on the same day with the Harvard University dedication of Emerson Hall. Four

years earlier Dorr had been charged by the overseers with raising sufficient funds to erect a facility to

house Harvard's philosophy and psychology departments.

Two months later (February 17, 1906), Wharton informs Dorr of the postponement of her

departure for Europe until March 10, expressing hope that she and her husband may yet be permitted

"a little visit" to Dorr's home-and extending an open-ended invitation to Dorr once they return from

Europe in June to pay us "a longer visit than last summer," the only evidence we have of Dorr's visit in

1905. A week later she writes to a mutual friend of theirs, Justice Robert Grant, that "your letter makes

me still more regretful that we have had to give up our plan of going to Mr. Dorr for a few days this

month,"2 yet on the next day she writes to Dorr that she expects him within the week in New York.

On her return from France later that year, she writes Dorr on August 21 asking him to come

to The Mount since Teddy is eager to show him the property "improvements." The next to last letter

is problematic since it is undated though contextually futs this time frame; it simply asks Dorr to arrive

on another date when "the Edward Robinsons, the Grant LaFarges, and Roger Fry (our new curator of

paintings at the Museum)"23 will be present. Concluding these known exchanges, Wharton writes to

him on July 24 in response to another invitation from him; she regrets that she must stay at The Mount

and work, although Teddy is especially sorry that they can't now have another "Bar Harbor Revisited."

There is more talk of flowers and again encouragement that Dorr visit in August or September and see

"the George Dorr path, the new pond, and other improvements."

This one-way correspondence provides unique biographical details about both individuals

and demonstrates Wharton's persistence in developing a relationship with Dorr not restricted

to horticultural matters; although Beatrix Jones Farrand is nowhere mentioned, her role in this

relationship cannot be overlooked. Wharton's repeated invitations to Dorr should not be treated

casually, recognizing that the Whartons were very selective in their invitations to The Mount. These

letters also show Wharton's sincere appreciation of Dorr's gardening counsel, demonstrated by

repeated references to "the Dorr path." Since this was the only physical feature of the estate named

for a person, it is reasonable to conclude that she is acknowledging the value of his advice. Finally, the

correspondence shows that the Whartons relished their shared Bar Harbor experiences and that they

were sincerely disappointed at not being able to accept Dorr's repeated invitations to his Boston home.

However, if written discussion of common acquaintances, literature, and one's emotional landscape

are the measures of deeper levels of friendship, then we have little evidence that they were "intimate"

friends-a highly selective term of endearment in that era.

82

WILD GARDENS

These letters lack specifics to flesh out the details of Dorr's path and the development of wild

gardens at The Mount and on Mount Desert Island. We do know that Dorr's indebtedness to the

pioneering work of William Robinson is documented in The Dorr Papers by the scores of references to

The Garden serial that Robinson launched shortly after the 1870 publication of The Wild Garden.

What is a "wild garden"? A logician. might dismiss this conjugation as an oxymoron. But

sidestepping this rationalistic approach, it could be argued empirically that a wild garden is a grouping

of what is native to a region prior to any efforts to "naturalize." Harvard Botanist M. F. Fernald in

"The Acadian Plant Sanctuary" similarly advocates the conservation of environments "which by good

fortune still remain in their natural condition."24 Judith B. Tankard's recent introduction to a reprint

of The Wild Garden points out that William Robinson was not advocating wilderness but "landscapes

enhanced by the use of carefree hardy, native plants. "25 Robinson also proposes placing "perfectly hardy

exotic plants under conditions where they will thrive without further care" and situates these

gardens

"on the outer fringes of the lawn, in grove, park, copse, or by woodland walks and drives."26

One of Dorr's objectives was to foster interest in the preservation of the beauty of native plants

threatened by the progress of development. Dorr recognized that woodland plants require woodland

conditions and that experimentation in naturalizing such plants requires consideration of a host of

environmental considerations (for example, climate, rock texture, shade, and so on). Indeed, wild

gardens were experiments, annual efforts to determine which new species would prosper and which

would not. Robin Karson could just as easily have been speaking of Dorr when she emphasized that in

the wild gardening of Warren H. Manning, "the failures were as interesting as the successes. "27

Even after Wharton departed from The Mount, wild plant botany was still viewed as a

youthful enterprise. Commenting in print on Dorr's Acadian plant sanctuary proposal in 1914,

landscape architect C. Grant LaFarge emphasized that "to acquire this knowledge under present

conditions is well-nigh impossible. The country is too vast; its flora too scattered. Even the most superb

examples of wild growth are but stimulating suggestions

Your plan offers all of this. "28

The Wild Gardens of Acadia, established by Dorr in 1916, was described by Beatrix

Jones Farrand as "an offshoot corporation" of the Hancock County Trustees. Its purpose was to

cooperate with the federal government in developing a seacoast national park that would not only

conserve Acadian flora and fauna but go beyond the National Park Service mandate and provide

"opportunities for observation to students of plant life, of gardening, forestry and landscape art"

of native plants in legally protected sanctuaries accessible to future generations, undiminished in

diversity of genera and species. 30

As an advocacy instrument, the Wild Gardens of Acadia published ten small but widely

circulated monographs (part of the Sieur de Monts Publications series, 1916-18) promoting public

understanding of Acadian flora and fauna. set within the cultural. historic. and scientific, justifications

for conserving more of the available island. The corporation also acquired land-much of it donated

by Dorr-that was then turned to purposes consistent with its mission. The most enduring and visible

expression of Dorr's application of the Wild Gardens of Acadia corporation is the Mount Desert Island

Biological Laboratory, established in 1921; today this scientific enterprise is a world-famous center

for the study of epithelial transport, the physiology of marine vertebrates, and the toxic effects of

environmental pollutants. 31

83

RONALD H. EPP

As the Country Place Era unfolded, the "wild garden" concept continued to be open to

diverse interpretations. In his memoirs, written during the last decade of his life, Dorr presents a view

of wild gardens that I believe he proposed to Wharton nearly forty years earlier: namely, that they are

"permanent gardens of naturalization where the hardy flowering plants, herbaceous and woody, might

be planted in generous groups as though native to the region and become an outstanding exhibit of

what might be planted and grown permanently in it in favorable locations

that brings that beauty

out by proper placing and artistic background so as to be in harmony with the landscape and a feature

of it."32 We are left to wonder whether there is any evidence that Wharton would have agreed with the

similarly expressive language of Mariana Van Rensselaer, who characterizes the naturalistic gardener

as one who produces "many effects which, under favoring conditions, Nature might have produced

without man's aid. Then, the better the results, the less likely it is to be recognized as an artificial and

artistic result; the more perfectly the artist attains his end, the more likely we are to forget that he has

been at work."

Even those who have walked only the most accessible parts of the current Mount property

realize that marble ledge outcrops are enduring landscape features. These natural objects were not

removed and were critical concerns in siting the drive, the house, and the formal gardens. The

effect of these rocky ledges is a matter of perspective, clearly softened when viewed from the upper

story windows. The Mount itself is deliberately nestled within unseen rocky ledges that define the

foundation, and it appears that Wharton deferred to the natural constraints of the rocky landscape.

Further evidence of the preference for natural landscape is the simple fact that of the 113

acres of the estate, only 10 percent was given over to the placement of physical structures and formal

Figure 5. Oldfarm estate, Bar Harbor, Maine. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service, Acadia

National Park's William Otis Sawtelle Collections and Research Center.

84

WILD GARDENS AND PATHWAYS AT THE MOUNT

gardens. But there are no further details about the selection, development, and use of the property.

Possibly the Whartons' real estate agents advised their clients to acquire sufficient woodland to broaden

and protect the outlook. It is unknown whether plans were developed for garden expansion into the

available woodland.

Wharton's resources may not have been the constraining factor; instead, she may have heeded

Gertrude Jeykll's advice that "the size of a garden has very little to do with its merit. Jekyll, creator of

the exceptional gardens at Munstead Wood, knew from experience that large gardens can enslave their

caretakers. Aside from the labor commitment, however, Jeykil's argument is clearly aesthetic: if one

has considerable acreage, "a great part had better be laid out in wood [for] woodland is always restful

and enduringly beautiful."36 More specifically, she cautions against the then-fashionable efforts at

placement of garden plants in wild places: "Wild gardening is a delightful, and in good hands, a most

desirable pursuit, but no kind of gardening is so difficult to do well, or is so full of pitfalls and of paths

of peril."37 Dorr had the right "hands" for this task: wide travel and a scholarly disposition made him

well versed in European horticulture traditions, his family legacy was couched within the geographical

limitations of New England gardening, and as a nurseryman he was thoroughly familiar with what

could and could not be accomplished in the environment of the Maine coast or the Berkshire landscape

of his boyhood.

Did woodland paths wend their way throughout The Mount property? More than twenty

years ago, Harvard Graduate School of Design scholars affirmed that the flower garden "linked into

adjacent areas with sinuous curving paths emanating from both ends of the east-west axis

[and] the

other sinuous path, to the east, disappeared around the small mount into the meadow en route to the

lake."38 Furthermore, David Bennett refers to "an extensive system of paths for walks and rides [that]

extended into the woodland, and linked the Mount's grounds to adjacent estates. 39

THE DORR PATH

We cannot be certain that Wharton involved Dorr in the design of his named path-or other

paths-but it is not unreasonable to infer that this path was named for him because of his dominating

influence on its character. His decades of experience as a Mount Desert Island trailbuilder might

suggest paths of roughly uniform width and rough surface. But this would surely have been considered

inappropriate-to impose- paths designed for the unusually rugged Maine coast into the Berkshire

Hills. The graduated materials used as borders for Wharton's formal gardens might also have been

incorporated into pathways, becoming more rustic as one walked away from the house. Or she and

Dorr might have weighed the merits of paths of uniform character in order to make them inviting to

her more formally attired guests.

Arguments could be advanced to show that Dorr favored the rugged, forested terrain west of

the property entrance for path development because of his formidable trailbuilding experience with

the severe Mount Desert Island mountains (figure 5). On the other hand, the Dorr memoirs contain

frequent descriptions of path development on less severe topographies such as the Great Meadow

development and its garden paths into downtown Bar Harbor. Indeed, one of his earliest successes was

constructing and landscaping a nearly mile-long bicycle path through a marshy beaver pond in Bear

85

Brook Valley, developed in the mid-1890s to allow his aging mother walks and gentle carriage rides.4 40

In view of available evidence, it is most likely that Dorr advised Wharton on the suitability

of paths to access wild gardens and recommended that she consider linking paths with more formal

walkways. He may have proposed tying these paths to adjacent properties; he played a role in carrying

out a similar plan at that time for linking Mount Desert Island town paths.

Through the expertise of Beatrix Jones Farrand and George B. Dorr, an island off the coast of

Maine would leave its imprint on The Mount. Regrettably, we cannot speak with finality on Wharton's

garden design intentions for the last five years of her residency. Dorr's experience with paths and wild

gardens on Mount Desert Island may have been applied to the Lenox site, but de locacion of these

landscape features remains unknown. Finally, no property map bears the "Dorr path" name that

Wharton repeatedly claims as an established landscape feature. This omission leads me to conclude that

at one time the Dorr path wended its way through the property-until the woods reclaimed it.

NOTES

1

Edith Wharton's letters to George B. Dorr are contained in folder 753, box 24, in the Edith Wharton Collection, Yale Collection

of American Literarure, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library (New Haven, CT).

2 The exception to this is Eleanor Dwight's Edith Wharton: An Extraordinary Life (New York: Abrams, 1994), 116.

3 Richard S. Jackson Jr. and Cornelia Brooke Gilder, Houses of the Berkshires, 1870-1930 (New York: Acanthus, 2006).

4 Thomas Wren Ward papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston.

5

Edward Waldo Emerson, The Early Years of the Saturday Club: 1855-1870 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1918), 110. The Ward

family estate Highwood was located near Highlawn, which belonged to George B. Dorr's paternal aunts and uncles prior to Dorr's

acquisition of the property. Highlawn is the largely forgotten predecessor to Blantyre, an opulent Tudor-style cottage that is now

run as a country-house hotel.

6 The Bar Harbor Historical Society Museum holds the Dorr memoirs, The Dorr Papers. A Guide to 'The Dorr Papers' (2004) has

been prepared by this author and is available with microfilm copies of Dorr's memoirs at the Jesup Memorial Library, Bar Harbor,

ME, and the Sawrelle Research Center, Acadia National Park.

7

S.B. Sutton, Charles Sprague Sargent and the Arnold Arboretum (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970), chap. 1.

8

Dorr Papers, B2.f.2.

9 Ibid., B1.f.14.

10 Minutes of the Bar Harbor Village Improvement Association, Bar Harbor Historical Society Museum (Bar Harbor, ME).

11 William James, The Correspondence of William James, vol. 2, ed. I. K. Skrupskelis and E. M. Berkeley (Charlottesville: University

of Virginia Press, 1993), 46, 272. In addition to entertaining James family members in 1886 and 1893, the Oldfarm guest book

documents visits in 1897 and 1907.

12 Beatrix Farrand, "The National Park on Mount Desert Island," Scribner's Magazine 61 (April 1917): 484-94. Farrand family

respect for George Dorr is also evident in Max Farrand's September 1932 correspondence with John D. Rockefeller Jr.,

Rockefeller Archive Center, III.2.I. B110. f.1093, Sleepy Hollow, NY.

WILD GARDENS AND PATHWAYS AT THE MOUNT

13 Bar Harbor Record, May 8, 1901; Bar Harbor Times, April 18, 1928.

14 Sutton, Charles Sprague Sargent, 18, 327.

15 Bar Harbor Record, May 8, 1901.

16 Ibid.

17 Edith Wharton quoted in Millicent Bell's Edith Wharton and Henry James (New York: Braziller, 1965), 78.

18 Minutes for the Hancock County Trustees of Public Reservations are archived at the Woodlawn Museum, Ellsworth, ME.

19 The Story of Acadia National Park,. ed. (Bar Harbor, ME: Acadia Publishing, 1997).

20 House Guest Book 1895-1996, Biltmore Estate Archives, Asheville, NC.

21 Edith Wharton to George B. Dorr, December 28, 1902. Edith Wharton Collection, Yale Collection of American Literature,

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library (New Haven, CT).

22 Edith Wharton to Robert Grant. Edith Wharton Collection, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and

Manuscript Library (New Haven, CT).

23 In 1906, English artist and critic Roger Fry (1866-1934) was appointed curator of paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

in New York City.

24 Sieur de Monts Publications 5 (1916): 2-9.

25 Judith B. Tankard, introduction to The Wild Garden, by William Robinson, reprint (Portland, OR: Sagapress, 1994), xiii.

26 William Robinson, preface (1881) to The Wild Garden, reprint (Portland, OR: Sagapress, 1994), xvi.

27 Robin Karson, The Muses of Gwinn (Sagaponack, NY: Sagapress/Abrams, 1995), 131.

28 C. Grant LaFarge, in George B. Dorr, "Garden Approaches to the National Monument," Sieur de Monts Publications 17 (1919):

11. See also Ronald H. Epp, "George Dorr's Vision for 'Garden Approaches to Acadia National Park," Chebacco: The Magazine of

the Mount Desert Historical Society 4 (2004): 55-63.

29 Farrand, "The National Park," 494.

30 Wild Gardens of Acadia: By-Laws. Rockefeller Archive Center, III.2. I. B.85.f. 840. Sleepy Hollow, NY.

31 Franklin H. Epstein, ed., A Laboratory by the Sea (Rhinebeck, NY: River Press, 1998) discusses extensively the role of Dorr and

the Wild Gardens of Acadia in the establishment of the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory.

32 Dorr Papers, B3.f.1.

33 Mariana Van Rensselaer, Art Out-of-Doors (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1893), 4. See her Accents as Well as Broad Effects,

ed. David Gebhard (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

34 Wendy Baker, David Bennett, and Diane Dierkes, Landscape Architectural Analysis and Master Plan for The Mount (Lenox, MA:

Edith Wharton Restoration, Inc., 1982).

35 Gertrude Jeykll, Wood and Garden, reprint (Woodbridge, UK: Antique Collectors' Club, 1981) chap. 14.

36 Ibid., 249.

37 Ibid., 358.

38 Baker, Bennett, and Dierkes, Landscape Architectural Analysis, 58.

39 Eleanor Dwight, in Edith Wharton: An Extraordinary Life, 94, credits this claim to David Bennett.

40 Dorr Papers, B2.f. 6 and 7. See also Margaret Coffin Brown, Pathmakers: Cultural Landscape Report for the Historic Hiking Trail

System of Mount Desert Island (Boston: Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation/National Park Service, 2006), 55-59, 67-74.

87

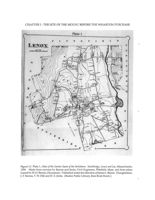

CHAPTER I - THE SITE OF THE MOUNT BEFORE THE WHARTON PURCHASE

Plate 1

P

I

T

T

S

F

I

E

L

D

LENOX

B

E

L

Figure I.2 Plate 1, Atlas of the Garden Spots of the Berkshires: Stockbridge, Lenox and Lee, Massachusetts,

1894. Made from surveys by Barnes and Jenks, Civil Engineers, Pittsfield, Mass. and from plans

loaned by W.H. Barnes, Housatonic. Published under the direction of James L. Beirne. Draughtsmen,

J.P. Barnes, T. W. Hill and H.E.Jenks. [Boston Public Library, Rare Book Room.]

CHAPTER II - EDITH AND TEDDY WHARTON AT THE MOUNT, 1901-1911

Carnduff

Paterson

Interlaken

Est.

Clipston

Warm

Goelet

Southwood

Lessee

Estate

R.W

The Mount

Merrywood

Chas

Buller

LAUREL

LAKE

The Poplaus

Samuel

Frothingham

I

Ersk

Erskine Park

Mrs. Geor

Mrs.

Westinghouse

Highlawn Farm

Figure II.1 Plate 22 from the 1904 Barnes and Farnham Atlas of Berkshire County, Massachusetts

(M&P-1). [SM]

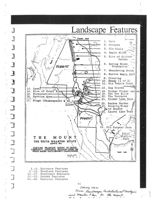

Landscape Features

Plunker Street

1. Gate

2. Orchard

3. Old Field

4. Maple Allee

5. Site of Kitchen

Garden

6. Spring House

FOREST

Foundation

7. Meandering Brook

o

8. Narrow Maple Port

9. Clearing

10. Swamp (1 of 2)

11. Old Tennis Court

13. Lawn

12. Dog Graves

14. Site of Giant Elm

18. Former Flower Garden

15. Forecourt

19. The Two Hills

16. Service Area

20. The Terraces

21. Former Lime Walk

17. Stage (Shakespeare & Co.)

22. Sunken Garden

23. Pergola/Steps

to Meadow

24. Laurel Lake Pond

FOREST,

25. Old Sargent Farm

26. Edith

THE M o UN T

Wharton

Park

THE EDITH WHARTON ESTATE

LENOX. MA.

HARVARD GRADUATE SCHOOL OF DESIGN

COMMUNITY ASSISTANCE PROGRAM-SPRING 1982

WENDY BAKER . DAVID BENNETT-DIANE DIERKES

Laurel Lets

1.-5. Entrance Features

6.-12. Woodland Features

13.-17. Forecourt Features

18.-23. Garden Features

24.-26. Pastoral Features

61

SPRING 1982

From Landscape architectural analysis

and master Plan for The mount.

1/2

in

BOX is

MUNTIN

1/14

2646

CLASS

2/2

x

it's

&

M

If

STILE

My

SECTION DETAIL NO BCALE

WEST ELEVATION

SCALE -1-0"

THE MOUNT GREENHOUSE

N

SCALE m-1-0

LENOX, MASS.

BUILT IN 1902

FRANCIS HOPPIN HOPPIN & KOEN ARCHITECTS

NEW YORK, N.Y.

drawn C. 1988-90 - by Yoshi Sato For Terry Hallock

Architects

Map of 2 Plunkett St Lenox, MA by MapQuest

Page 1 of 1

Sorry! When printing directly from the browser your map may be incorrectly cropped. To print the

entire map, try clicking the "Printer-Friendly" link at the top of your results page.

MAPQUEST

8

2 Plunkett St

Lenox, MA 01240-2704, US

Sorry! When printing directly from the browser your map may be incorrectly cropped. To print the

entire map, try clicking the "Printer-Friendly" link at the top of your results page.

enox

183

20

7

Lily

Pond

7A

Cranwell

Resort

Golf

20

Club

Stockbridge

Bowl

Lenox Dale

7

Laurel

Lake

Summer

St

Interlaken

800 E

'0

2400ft

MAPQUEST

CH 2007 MapQuest Inc.

2007NAVTEQ

All rights reserved. Use Subject to License/Copyright

This map is informational only. No representation is made or warranty given as to its content. User assumes all risk

of use. MapQuest and its suppliers assume no responsibility for any loss or delay resulting from such use.

http://www.mapquest.com/maps/map.adp?formtype=address&country=US&popflag=0&la.. 4/27/2007

First published in the United States of America in 2004

by Rizzoli International Publications, Inc.,

300 Park Avenue South, New York, NY IOOIO

www.rizzoliusa.com

Text @ Edith Wharton Restoration, Inc. 2003.

Photographs @ Jonas Dovydenas 2003.

Used with permission. All rights reserved.

"EDITH WHARTON" and "THE MOUNT" are trademarks belonging to Edith Wharton

Restoration, Inc. See www.edithwharton.org.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior consent of the publishers.

2004 2005 2006 2007/ IO 87654321

Distributed in the U.S. trade by St. Martin's Press, New York

Printed in China

ISBN: 0-8478-2609-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wharton, Edith, 1862-1937.

2004

The cruise of the Vanadis / Edith Wharton;

photographs by Jonas

Dovydenas.- - Ist American ed.

p. cm.

ISBN o-8478-2609-0

I. Mediterranean Region-Description and travel.

2. Wharton, Edith, 1862-1937-Travel-Mediterranean Region.

3. Americans-Mediterranean Region-History.

4. Vanadis (Frigate) I. Dovydenas, Jonas. II. Title.

D973.W56 2004

910'.9163'809034-dc22

2003025705

Page 3: Steam yacht VANADIS of 1880 © Mystic Seaport, Mystic, CT

Page 224: Image of Edith Wharton. Reprinted by permission of the estate of Edith Wharton

and the Watkins/Loomis Agency.

E

dith Wharton in her memoirs, A Backward Glance, relates how in the

winter of 1888, then a bride of three years, aged twenty-six, she

confided in a Newport friend and cousin-in-law, James Van

Alen, that she would give anything in the world to make a cruise in the

Mediterranean. But she was not prepared for his answer: "You needn't do

that if you'd let me charter a yacht and come with me."

Van Alen meant what he said. He was a hearty and adventurous

soul, a world traveler, a.member of an old Knickerbocker family and the

widower of Edith's second cousin, Emily Astor who had died in child-

birth. He had volunteered to fight the Turks in Greece in Lord

Mulcaster's ill-fated expedition in the 1870s, but had fortunately been

prevented from going by a last minute attack of malaria. He was rich

enough to pay his half of the charter of the yacht Vanadis, but Edith and her

husband Teddy had to come up with their half, which they sportingly did,

though it amounted for them a full year's income. Luck, however was on

their side, for a distant cousin of Edith's died while they were at sea, and

her unanticipated share of his estate more than covered the cost of a

cruise which Edith called a "taste of heaven."

The account that she kept of this excursion is the only writing of

hers of which we have any knowledge, except for some juvenilia, from the

first quarter century of her life. As a published writer she was certainly a

late starter. Keats was dead at an age when she had still not begun. But

those earlier years had not been wasted. She not only read deeply in

English, French, Italian and German literature; her keen eyes had taken

in and her copious memory had recorded the myriad details of her child-

hood visits to Europe and her home life in brownstone Manhattan and

the shingle villas of Newport. She had stored a gallery in her mind from

which she would be able to illustrate the many volumes she was destined to

write.

The portrait that the French novelist, Paul Burget, provided of a

Newport intellectual matron in Outremer (1893) has long been recog-

nized as Edith Wharton. She "has read everything, understood every-

thing, not superficially but really, with an energy of culture that could put

to shame the whole Parisian fraternity of letters." And yet he found him-

THE CRUISE OF THE VANADIS

I5

selflonging to cry, "Oh, for one ignorance, one error, just a single one!"

But he longed in vain.

One can see a little of what he means in reading the account of

her cruise. Edith Wharton's observations are SO richly detailed, so vividly

expressed, and, one is sure, with so unerring a taste, and SO accurate a

rendition, that one wonders at times if any tourist could really be so

exquisitely equipped for the experience of travel. Yet any such begrudg-

ment is soon swept away by the excitement of feeling that one is witnessing

the genesis of a great literary career. Edith Wharton was not going to sub-

ject herself or the public to the spectacle of any awkward first steps; all of

these would be kept to herself until she was ready to present a really fin-

ished product. The style of her first published work of fiction, "The

Greater Inclination" (1890), did not have to be improved upon for the

rest of her long literary life. In her log of the Vanadis we have a kind of

dress rehearsal for the fiction of one of America's greatest novelists.

The diary, if diary it was-and the sharpness of its details certainly

suggests an almost daily recording-is strictly limited to just what Edith saw

at each Ionian or Aegean stop. One occasionally has a glimpse of the

author's sometimes rather domineering personality in her admissions

that her rigorous schedule of exhaustive sightseeing may have caused a bit

of a strain on her two more easygoing male companions, and we note that

she found the captain surly and indifferent. There are also moments

when she voices her dissent from popular opinion, as when she suggests

that the famous Sicilian cathedral at Monreale lacks depth and variety of

color, or when she disagrees with those romantics who find ruins

improved by their very dilapidation. How the architect of the temples at

Girgenti, she exclaims, would have shuddered to think that "his raw

masses of sandstone would remain exposed to the eyes of future critics!"

For the most part, however, the beauties of nature and ancient

civilization speak for themselves in her vivid and elegant prose, and the

splendid photographs of Jonas Dovydenas of the actual scenes she

describes shed a fascinating modern light on a world that has actually

changed very little since the cruise of the Vanadis-and where it has changed

tourists would not be anxious to penetrate. The industries of the day,

THE CRUISE OF THE VANADIS

16

Edith states, might be a source of pride to modern Greeks, "but very

uninteresting to the traveler who has hoped in sailing eastward to leave the

practical realities of life behind."

So minutely does Edith observe the phenomena that attract her

that it is hard to believe that she was only a day or two in most of the sites

visited. Take for example this description of what the women of Amorgos

had on: "They wore linen petticoats grotesquely embroidered with images

of beasts and birds in red and green silks, and some had linen jackets, still

more elaborately embroidered, with enormously wide sleeves; while oth-

ers wore skirts and jackets of scarlet cloth. All of them had chemisettes of

gold-embroidered gauze and necklaces of old coins; while their heads

were wound in long yellow scarves falling to their shoulders."

One can see in the diary the trained eye that would one day

enable its possessor to recreate the gleaming overstuffed Victorian interi-

ors of Fifth Avenue and the small bright lawns and big bright sea of

Newport, as so unforgettably depicted in The Age of Innocence. Edmund

Wilson would call Edith Wharton the pioneer and poet of interior deco-

ration, but her gardens were just as fine as her houses, in her books as in

her life.

We see in what she wrote about her cruise that she was ready to set

her stages, to fill her backgrounds, to create the world in which her char-

acters would enact her plots. The characters and plots would come in

due time.

THE CRUISE OF THE VANADIS

I7

3 4600 00503 4779

ITALIAN VILLAS

AND THEIR GARDENS

BY

EDITH WHARTON

ILLUSTRATED WITH PICTURES BY

VILLA CAMPI, NEAR FLORENCE

MAXFIELD PARRISH-

AND BY PHOTOGRAPHS

LIRE

NEW YORK

THE CENTURY CO.

1904

VIVIAN

R USSELL

Part

E DITH

WHARTONS

ITALIAN

GARDEN'S

A Bulfinch Press Book

Little, Brown and Company

Boston . New York P Toronto . London

Edith Wharton's home at the Mount in Massachusetts was inspired by

Edith would take. She may well have written the articles in the

Belton House in England, at the time assumed to be by Sir Christopher Wren.

atmospheric, painterly vein of her writing in her novel, had she

From her second-floor apartments, where she spent the mornings writing,

not discovered quite quickly into her researches that no serious

Edith could look out over the clipped box, geometrical parterres and statues of

work on Italian gardens existed in English. The 1894 peregrinations

the Italianate garden she had created. The garden and surrounding landscape

of Charles Platt, a landscape architect and friend and neighbour of

are recognizable in descriptions in her novel The House of Mirth,

Parrish's in Bar Harbour, Maine, had produced some splendid

published three years after she moved there.

photographs of less than two dozen of the grandest gardens, but

the accompanying text contained not a single date or architect,

The editors at Century Magazine thought that this poetry-in-prose

and Edith instantly recognized the potential of SO interesting and

rendering of an Italian garden would perfectly complement the

unexplored a subject: 'having been given the opportunity to do a

romantic style of the artist Maxfield Parrish. Shortly after the Valley

book that needed doing, I resolutely took it.' After the critical

of Decision was published, they asked Edith to write a series of

success of The Valley of Decision, 'nothing would appease her creative

articles to accompany paintings of Italian gardens by him. She was

and critical appetite', noted her biographer, Professor R. W. B.

enthusiastic about the idea, as Parrish had already illustrated one

Lewis. She tackled this project with what Paul Bourget dubbed

of her short stories. The Century editors, confident that her prose

energy of culture', which Henry James sometimes found

would be as rhapsodic as Maxfield Parrish's 'moonlight and

overwhelming, describing the experience of 'travelling under the

nightingale' fantasies, underestimated the high-minded approach

spur' with the 'rich, rushing, ravening' Whartons.

L

EDITH WHARTON AND ITALY

Edith fully understood that the Italian garden had

almost nothing to do with the art of gardening and

everything to do with the garden as a work of art.

Principles of architecture, the study of painting,

sculpture and architectural detail were all disciplines

she had long schooled herself in, and which had given

her an excellent grasp of the 'plastic arts'. Spanning

many years, her reading of Italian literature, poetry

and mythology had been comprehensive. In the

Renaissance garden, seeped in symbolism, allegory and

the visions of poets, she would recognize the

enchanted gardens of Tasso, the fables of Ariosto, the

philosophy of Petrarch, the spiritual journey of Dante

and how these writers were inextricably bonded to the

old Italian garden, as indeed was the whole cultural

background of Italy.

Edith launched herself into the uncharted waters

of her Italian garden voyage on 3 January 1903, when

she and Teddy sailed for Genoa. Now fifty-four, Teddy's

underlying mental instability was beginning to surface.

The doctor had ordered him to spend time in wintery

sunshine, and SO for three weeks Edith sat under a palm

tree in detested San Remo, impatient to be off

prospecting for the gold of the Italian garden. From

San Remo the Whartons went to Genoa, and from

Genoa to Rome, where they arrived at the end of the

first week in February for a month's stay.

From Rome Edith wrote to her childhood friend

Daisy Chanler, 'You don't need to be told, I am sure,

that I have thought of you very often in scenes which

are SO associated with you. We have been here a month,

and we leave, alas, the day after tomorrow, with a sense

at once of regret and repleteness. I think sometimes it

is almost a pity to enjoy Italy as much as I do, because

the acuteness of my sensations makes them rather

E The fashionable and successful Mrs Wharton in Paris in 1907, a

exhausting. The highlight of the stay was undoubtedly her first

d when she was enjoying the fame earned by her novel The House of

experience of a motor car, driven by the American ambassador,

, which had become a bestseller.

George Meyer, from Rome to Caprarola, a round trip of 100 miles

that she was astonished could be accomplished in an afternoon.

SITE The and gold inclept to the first edition of

LEFT Robert Norton's watercolour

four

of Edith Wharton's last garden at

Plac

Pavillon Colombe, Saint-Brice,

refe

complements the description left by

othe

a visitor in the 1930s: 'there was an

the

atmosphere of repose and other-

world so strong that one shed one's

forg

present day self at the threshold

Through the window my eyes

of

rested among the green trees whose

you

trunks were shot by the late sun-

grea

rays. Stone jars with pink climbing

tida

geraniums stood out against the

only

vivid fat grass of a wet summer, and

the smell of box rose pungently from

chu

the formal clipped hedges.'

her

OPPOSITE Edith Wharton on

the

the terrace at Sainte-Claire in the

first

1930s. Beside her are her

sper

housekeeper Gross and her little

frie

dogs who always accompanied her

on her travels.

her

Edith Wharton cared for her gardens with passionate devotion.

rendering of a garden that elicited the comment from the Austrian

She ministered to her plants as if they were young charges; perhaps

ambasssador, as he looked out from the terrace over a formal

it

garden, rock garden, trees, rolling hills and lake: 'Ah, Mrs Wharton,

bec

they replaced the children she never had. 'Edith was very learned

about gardens, reported Berkeley Updike, the stylish printer of

when I look about me I don't know if I am in England or Italy.'

ma

her books, on a visit to the Mount, and she and a neighbour, Miss

She never made a garden in Italy, seeming to have exhausted

Charlotte Barnes, used to hold 'interminable and to me rather

her subject, and henceforth treated it, she said, as 'dessert' whilst

she

boring conversations about the relative merits of various English

France became her 'daily bread'. She made two gardens in France,

seedsmen and the precise shades of blue or red or yellow flowers

her two saints she called them: Saint-Brice outside Paris, and Sainte-

that they could guarantee their customers. I have never thought it

Claire, built on an Hyères hillside overlooking the Mediterranean.

very interesting to hear about other people's gardens and have

She spent her winters there in the company of two of the greatest

laughed at the prosey discourses of their owners until I had one of

gardeners of this century, Lawrence 'Johnnie' Johnston and her

hop

my own, when I found myself victimizing guests in precisely the

neighbour Charles de Noailles.

same way.'

The art critic Bernard Berenson had by this time replaced Walter

Although she commissioned her niece Beatrix Farrand to design

Berry and Henry James as her intellectual confidant. Bernard and

the kitchen garden at the Mount, Edith wanted to do the rest of

his wife Mary Berenson's villa, I Tatti, near Florence, became her

the landscaping there herself. Teddy was also involved, 'opening

spiritual home and she visited them every year, usually en route to

a

up vistas through trees' with mixed results. In her later years,

or from Hyères. Sainte-Claire, she wrote to Berenson, was no mere

sme

Edith admitted how her Italian book influenced the Italianate

parterre of heaven; it is the very "cielo della quieta" that Dante

dise

VISITING

In cases where different

guidebooks give different names

for the same villa, alternatives

have been given, after the name

THE

used in this book. Relevant

phone numbers have been

supplied where available. It is

GARDENS

worth telephoning first, as some

villas may be open only by

appointment.

LOMBARDY

ISOLA MADRE

28050 Isole Madre (VB)

Tel: 323 31261

One of the Borromean Islands, on

Lake Maggiore; reached by boat

from Stresa, Baveno or Pallanza

ISOLA BELLA

28050 Isola Bella (VB)

Tel: 323 30556

One of the Borromean Islands, on

Lake Maggiore; reached by boat

(

1

from Stresa, Baveno or Pallanza

3

VILLA D'ESTE

7

Via Regina 40

(

22012 Cernobbio (CO)

I

Tel: 031 511471/512471

On the west shore of Lake Como,

I

33 miles/53 km N of Milan and

\

3 miles/5 km N of Como

3

7

VILLA CARLOTTA

(

Via Regina 2

22019 Tremezzo (CO)

Tel: 344 40405/41011

I

On the west shore of Lake Como,

A

18 1/2 miles/30 km north of Como,

3

on the S340 between Tremezzo

7

and Cadenabbia; or by boat

1

from Bellagio or Como

3

0

via Aurelia Antica,

21050 Bisuschio (VA)

37023 Grezzana (VR)

Tel: 55 697205

Via di S. Pancrazio

name

Tel: 332 471134

Tel: 45 907045/907135

1 1/4 miles/2 km on the far side of

or Via Vitellia

5 miles/8 km north of Varese

5 1/2 miles/9 km north of Verona

Settignano, 5 miles/8 km north-

00165 Rome

on the S344

t is

towards Negrar

east of Florence

Tel: 6 5899359/5813717 (tours)

South-west of the city centre,

some

entrance beyond the Porta San

VENETO

FLORENCE

SIENA

Pancrazio

VILLA PISANI

VILLA PRATOLINO

VILLA GORI

CAPRAROLA

Via A. Pisani 6

Parco di Villa Pratolino

Via di Ventena 8

Villa Farnese

30039 Stra (VE)

Demidoff

53100 Siena

Piazza Farnese

Tel: 49 9800590

loc. Pratolino

Tel: 39 577 2209 (tourist office)

01032 Caprarola (VT)

On the Brenta canal, 5 miles/8 km

Via Fiorentina 6

North of Siena on the road to

Tel: 761 646052

east of Padua on the S11

50030 Vaglia (FI)

Vicobello near the Monastera

11 miles/18 km south-east of

Tel: 55 2760529-538

Osservanza

Viterbo off the Via Cimina

is, on

CASTELLO DEL CATAIO

7 1/2 miles/12 km north of Florence

oat

35041 Battaglia Terme (PD)

VICOBELLO

VILLA D'ESTE

nza

Tel: 49 526541

VILLA CASTELLO

Villa Vicobello

Piazza Trento 1

About 10 1/2 miles/17 km south-west of

Villa Medici Castello

Via Vicobello 12

00019 Tivoli (Roma)

Padua on the SS16 towards Monselice

loc. Castello

Vico Alto

Tel: 312070

Via di Castello

53100 Siena

Town centre, 18 1/2 miles/30 km

GIUSTI GARDENS

50141 Firenze

Tel: 39 577 2209 (tourist office)

east of Rome on the S5

ds, on

Giardino Giusti/Palazzo Giusti

Tel: 55 5 454791 (porter's lodge)

Just outside the city walls of Siena

oat

Via Giusti 2

South of Sesto Fiorentino, 3 1/2

VILLA LANTE

nza

37129 Verona

miles/6 km north-west of Florence

CETINALE

Via J. Barozzi 71

Tel: 45 8034029

Villa Cetinale

01031 Bagnaia (VT)

City centre, on the east bank of the

BOBOLI GARDENS

Cetinale

Tel: 761 288008

River Adige

Piazza Pitti 1

Sovicille

1 3/4 miles/3 km east of Viterbo

50125 Firenze

53018 Siena

PADUA BOTANIC GARDEN

Tel: 55 218741 (tours)

Tel: 39 577 2209 (tourist office)

VILLA ALDOBRANDINI

Como,

Via Orto Botanico 15

and

City centre, behind the Pitti Palace

8 miles/13 km south-west of

Via G. Massaia 18

35123 Padua (PD)

Siena, between Ancaiano and

00044 Frascati (Roma)

Tel: 49 656614

VILLA PETRAIA

Celsa, via the S73

Tel: 6 9426887

City centre

Villa Medicea della Petraia

13 1/2 miles/22 km south-east of

loc. Castello

Rome on the S215

VALSANZIBIO

Via della Petraia 40

ROME

Villa Barbarigo/Villa Pizzoni

50141 Firenze

Ardemani

Tel: 55 452691

VILLA MEDICI

Como,

Como,

35030 Valsanzibio di Galzignano (PD)

South of Sesto Fiorentino, 3 1/2

Via Trinità dei Monti

Tel: 49 9130042

miles/6 km north-west of Florence

00187 Rome

11 miles/18 km south of Padua,

On the Pincian Hill at the top of

t

31/2 miles/6 km west of Battaglia Terme

the Spanish Steps

OPPOSITE A rainy day at the

on the A13 or the S16

Jardin d'Amour at Isola Bella.

187

Manchester, A.

x

A

BACKWARD

GLANCE

by

EDITH WHARTON

Je veux remonter le penchant de mes belles

années

Châteaubriand: Mémoires d'Outre Tombe

Kein Genuss ist vorübergehend.

Goethe: Wilhelm Meister

DAVISION

D. APPLETON-CENTURY COMPANY

THE AUTHOR

INCORPORATED

NEW YORK

LONDON

1934

Sectude Jekyll

Wood and Garden

rptd.

Lade: Deen to 1981 (1899)

Month by mouth treatment.

Lage t Small garden

Pg 358

"Will gordeny is a delogetife,

and in good handsca most desidable,

yoursuit, but No herd of gordency

Lo so difficult to do well, or

IS 80 full f pitfall odd

paths of perit."

Says ,7 is now fashionable

" " ? understand to we

Marty exotics in will places

not can that ay guide plat iF,

placed 02 will place a wild youdy

She steme need for the "Not cauped

Considertia for ay wilt gardy.

f.359

The place "seeved tr ash for th

plasty a " fair in

picture value

Shanes the wond

Jour the gorden replant 88 that

the gorde influence pretrite the here of there,

Jekyle 2

the then. better to fairth one to the

p.H.

a guidencia a friend teacher Rt

track patience ad cauful

waterfulness; it teacher

Indu try + thrift, above all,

it teacher estire trust

Ch. 14 : Large Small gordens

"The size of a feeler has by lette

to do write it merit.

them hournuch carbe done un a

small space

P 242

"I do not envy the ourseen veg

large gording . the goide should

fit its master or his taste just

as he clothes do, it should be

neither too large nor too fail l net

just confortable,

is tru loup to wange,

the le become its slove.

of expecientry torese + their garden,

p 243

the 1sl they is to for laye unbroke

laun space

Als., a broad walk day Sunath

pubuls level hear ford word

Jebyll-3z lawn as bounded "G five fees,

244

away beyond that is all weld wood.

of carn the "wood world from into

shub plactations, ad father still

leb guide & wild achard -

ask

a garden should neveribe large

dings to butting ad if on

2.249

hase a laye space, "apeat

that # had better be loud aat

in wood Woodlarn always

realfal + deduringly beautiful, +

then the be intermediate kind

g wordland that should be made

more I - woodland the orchaed type."

Leon Edel. Henry James ? a Life

ny: Harper + Row, 1985.

Rev.versus of Hearz Jam. The Untreat

Years 1843-1870. etc.

PP.579F The Agreeable women,"

Whaton had "pursued" H.J.

R

would have more "men fueld than women

and they was dwgs men high in the life

of the country

What endesure her to HI was "that she pursoned

also a avilized mind ad art st's style."

1st net in Dec. 1903 despite executes in 1090's awells

Whitter descules have "the Nort intructe fuel

p.581

have wer had though in deg ways we were so different

597

Lody phenixy.

Heny James Letters Ed. hean Edil.

Haward U.P., 1 E80. Vol. 3

HY to WT. 9/10/86.

Refer to WY's short letter of 8/24 after

spet greater pat v visit in bed mt desert

w aat a bad placet to have missed in

p.131-2 that ay." HJ recall visit there c g James

before return England "I never sow a place

of which I understand less than itthould be

rovedabout - or even endured.

3 pp-letter to

VML 4

n HJ7. may Cadeshadee Jones from Rye 8/20/02.

HI to Sarah Butler Wister (daughter I Fanug Kenble)

for Rya 12/21/02.

Refersts Samuel G. Word as a person to whom

A-260

WJ "part wash vibrate(s).

HT to Edith Wdaction from Rye 11/8/05.

Refers to Eath Beatray who did net

look too well if of the would fiving

"Doctors ad waters "and connet the self

to the advice of "Livine Hetcher.

HJ to Edith, Rye, 10/4/07. He s y no he hoojjust

you H62

sput 5 day may & Beating in" requeste

weather expressed when?

at John Cadwaladers grousenoor."

HJ to Edith, By Cambridge (MA), 2/9/11. Again effer to

1.594

spendy too time in ny e May Beatras - -mod affectionality.

2. letters of Henry James

p. 669

HJ to Howard Shurgis, 5/12/13.

Effort to dear up ancestry issues.

" Gussy Baher un the son of z Grent Jonet (Janes)

the, day at but (I think) or very early nedes,

had married Willian B., brother of anna Barker",

mrs. S.G. Ward, the latter wife of the 'good'

Some ward, of boston, ad late the mother of

from dear deaf 'Tom' of Bossie vou Schonberg

(wife of Ernst) of Lily V. Hoffmann of the

old Roman days etc."

note: Sheya had be ready a small Bay +

Others Joanette James

( 1814-42 who married William H. Barker

in 1832 ad Seid jay butk to her 4th child,

Augustus Janes in 1842 Her second child

us Eliz abete Hojard Bacher, who married

George Hoggingon + died in 1901. (p.671).

# HJ to Edith Eye, 9/19/14.

Refers to Mary Cadinal as here. "atte thought

of eecing you, however, my eye does feel

itsey kindle..."

3/14/06 : lots

to understand the

as applied here a on MDI, are

rust first griff its creators - nus

Whatton - for Farmed and

The background interests f W.D.D.

catalyzed their Creater little

endsever + combend to Deshape

the garde at th mout

what Sevi W.co the better

humin of the bus, I'll form

trace some before ideas

that shoped Mr. Jani

developmet -and subquest

attraction to Mrs. W.

Parchpround of D.

-enghase Europea Travest

-

" garding traditions,

First lekel BH

Dorr - Cadwaladeria In B.H. (1881-83).

Beatrix Johnsonallection of

1883 Reef Print grouds

Both failte Dan. Whother, Farmed were

surforded g girlshy decerse cultural setting

*Seeps 2

2.

Doris Many knoots in BroSales the Borton

Dessociation c fracetical, act Acidy

lettery figures such as

Chach Dichen, margant fuller, etc.

contabrated the stimulested Dear

development, top Harvard Edwart

frouls, ad Park Street accommonant

avenu association formal been

of a Docul networ that proveded

durise opportunities for ones. Dau.

Cresm of Charle Sproper taynt-ude

lehon Intelly Beating which rate be

profedf refleced Does wound

friquity corresponded c the Hawark

address expects uped identifical

Anetabit of local flora

Ident ff travel locations - Englad,

Europe E gypt, ad the Seerra any

other trip X n.P.S. Conferences.

Ner vivid impressions of gailers

visited development Papers,

also in frendo monts pubs

moup Desert nursere opened in

1896, the you afte Beatrey Jone

reba for Europe & established

of hern.y. practice

3

We know heg letter of the walulu

of th MDNursew offer details

ald Farm - A its Gardens

1934 (?)

HAn 1930, the Garden Clut of America

Chose MDI for ets anual meet

locators, signal continuing status of

then garbers at a tan fut May

believed that the grande Sount are

of the Gelded aye had longwaneshield

JaWhit after scare of

gaiden visited, one l noted for

the havey acheved subs 3 that

true, what Patierh Charoe, calls,

"the peak In the gardus developut."

garden at Seal Harbor

of course the an the Albe Roelefalle Egree

note We don't know what:

- planting designs were wellyed

- the role of indigenous species

- wheller effect are thoroughly nebbratistic

a trial to the event, as at the Eyrie

- how planting elated to cultivated of views

- what trees were nature to property

- corobler scupture and ligeting were used to labouce

D whith Forrard budges would of feed input

4-

- was Old Farm we a nursery for

the commercial enterprese?

-

were wachings aparts used shore thogleat

the prepared or restricted fo a access

for the cottage ?

- was old form decorated c fresh

flowl anonputs few the proplef or

seurced s th MD nuseries ?

- as Dorrs experience e gords was refund

were there chaaps in the derection

of he guide that hrp acted - has profession

advice to gredever the Edith Whatton ?

-

Wh the a contray prequire for

personal an and (green amount

of certa colors ALCE ?

-

Thigh Dorr mode concerted efforest

the be attach no restrictions.

to preseure propers by gifty if to

Sadl, the property was reflected

its design healey has

been lost.

Site Visit

4/13/06

The Mount

Q.: Tax assessment-plastor of Old Farm?

Kitchen Sande designedy BFContainer

funts & vegetable covery 150x300'

now used as packing area between

gatehnm + stables July 1901.

Spunhhage at the Mout is Scounde elont

Rechech Whatton Uss. l illy Lobay, Indiana u

Edith is photograph might very cutical

of imaces taken of her!

less the 10% of landscape at the near give

over to placeaut of halses, outbuildings,

t freed gardening Remolide "wild'

(Di 113+

Earth at th blout did not ug on

the Mr. Dorr, + her our

may for bostrultural expect sc other

garden + Beatrix.

No moving imges of E.W. nor audio,

ZIW vez selective @ guests

2

4/13/06.

Wetlad adjocent to Forecourt.

Stream Hank house, one is rented

as cascade Houry to Lawel Puid.

under here t energes in funt center

bedges cradle" the Hout.

Roch outgrophing@abound

x

Rechech GeorgeCobot Lodge ("BAY"Lodge).

Would limiewall have bee extended out of

Red

formal gaid into wold garden

trid it loops around property ? Was

its composition graduated toward

len expensive -+ more natural-

Materialion Whaeta did C her borders.

Use of grass terraces body toward here

Verdant paths ?

Floriculture See Annette Handers

x

omarism Cruger Coffin, Ellen Ship ment

4 Edite Whenton neece.

Mrs Whaten' lettest GBD of a "technical" nature

accord to Betry.

4/14/06.