From collection Creating Acadia National Park: The George B. Dorr Research Archive of Ronald H. Epp

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

Page 62

Page 63

Page 64

Page 65

Page 66

Page 67

Page 68

Page 69

Page 70

Page 71

Page 72

Page 73

Page 74

Page 75

Page 76

Page 77

Page 78

Page 79

Page 80

Page 81

Page 82

Page 83

Page 84

Page 85

Page 86

Page 87

Page 88

Page 89

Page 90

Page 91

Page 92

Page 93

Page 94

Page 95

Page 96

Page 97

Page 98

Page 99

Page 100

Page 101

Page 102

Page 103

Page 104

Page 105

Page 106

Page 107

Page 108

Page 109

Page 110

Page 111

Page 112

Page 113

Page 114

Page 115

Page 116

Page 117

Page 118

Page 119

Page 120

Page 121

Page 122

Page 123

Page 124

Page 125

Page 126

Page 127

Page 128

Page 129

Page 130

Page 131

Page 132

Page 133

Page 134

Page 135

Page 136

Page 137

Page 138

Page 139

Page 140

Page 141

Page 142

Page 143

Page 144

Page 145

Page 146

Page 147

Page 148

Page 149

Page 150

Page 151

Page 152

Page 153

Page 154

Page 155

Page 156

Page 157

Page 158

Page 159

Page 160

Page 161

Page 162

Page 163

Page 164

Page 165

Page 166

Page 167

Page 168

Page 169

Page 170

Page 171

Page 172

Page 173

Page 174

Page 175

Page 176

Page 177

Page 178

Page 179

Page 180

Search

results in pages

Metadata

[Series VII] Samuel Gray Ward (1817-1907: 1850-1907) [File 2]

2

Source: 1Myerson, Editor.

298

Studies in the American Renaissance 1984

28 November: From Clifton Springs, New York, to Louisa May Alcott, Concord

27 December: From Concord to Ellery Channing, Concord*

1878

THE EMERSON-WARD FRIENDSHIP:

28? January: From Cambridge to Frances H. Prichard, Concord*

? March: From Cambridge to Ellen Tucker Emerson, Concord*

IDEALS AND REALITIES

18? March: From Cambridge to Ellen Tucker Emerson, Concord

David Baldwin

R

ALPH WALDO EMERSON'S FRIENDSHIP with Samuel Gray Ward,

a Boston aristocrat fourteen years his junior, marks the balance Emer-

son sought to keep in all things between his ideals and the world's realities.

It was a balance he could not often maintain: his idealism kept tipping the

scales. His adjustments, sometimes ambiguous, were not likely to serve as a

model for others, since they depended more on a steady temperament than

on his theorizing. Also, for that reason, they seem to have cost him little

agony. The friendship itself, which blossomed in the 1840s, a key period for

both men, grew from their common origins and from the social structure of

upper-class New England.

Ward and Emerson met infrequently. Seventeen miles separated Concord

from Ward's elegant Park Street townhouse in Boston, the distance helping

to stimulate a lively correspondence. Although Ward's have not survived,

Emerson's letters contain much to indicate why the younger man was of spe-

cial interest to him. Ward is of considerable interest in his own right, and

will' first be introduced as one who, though from the same roots, found him-

self first drawn towards but in the end away from Emerson's contemplative

approach to living and back to his mercantile family. With him the balance

tipped the other way, towards the worldly. From the first his was a far more

wealthy, more cosmopolitan, more social world. Though they developed into

close friends, Ward being as intimate a friend as Emerson ever had outside

of Concord, their lives inevitably diverged after the 1840s. The greatest value

in placing the two men side by side is that it illuminates Emerson's thought

and behavior on the subject of human relations.

Ward's origins, like Emerson's, were Puritan and patrician; but unlike his,

they were entirely from business and financial occupations. In common also

were parts of their schooling: Boston Latin School and Harvard College.

From a family always wealthier through generations, Ward had enjoyed the

299

300

Studies in the American Renaissance 1984

The Emerson-Ward Friendship

301

luxury of attending two private schools along the way, one of them the exper-

and orientation were too strong to be thrown off even by a bonding with the

imental Round Hill School in Lenox, Massachusetts. While both repre-

older man. Ward was a man of superior intelligence, and while some of that

sented elements of the ruling New England class back into the seventeenth

was pragmatic, another part was imaginative. Reflecting on the past in an

century, the differences in their income and occupational heritage placed

exchange of letters with Charles Eliot Norton near the end of his life, he

them in separate social groups. The Ward family was a member of Boston

wrote that Emerson had attributed to him a literary gift he knew he did not

society; Emerson's was not.

have. He knew even then that what little gift he had was "artistic." Nor was

This society was a tightly-knit group not unlike its counterpart in Phila-

he ever attuned to the substance of Emerson's messages: "In leaving his lec-

delphia in economic and social aspects. The Ward family had originated from

tures I never asked myself what were the doctrines or opinions he supported.

Salem, and Salem had fed certain families into the small elite that made up

When he began to speak it was himself, Emerson, that was the new fact he

Boston society in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Among those

expressed." The listener had a "vision of higher life" that, although clear for

from Salem, besides the Wards, were the Grays, Bowditches, Shaws, Cur-

the moment, could not be sustained.6

wens, Brookses, Sturgises, Pickmans, Bigelows, Saltonstalls, Endicotts, Pea-

During the 1840s and 1850s, Emerson plied Ward with advice on reading

bodys, and Gardners. Ward's father, Thomas Wren Ward, held for many

and with his own versions of the higher life. One of his recommendations is

years the distinction of being American agent for Baring Brothers of En-

especially noteworthy: "I have one more new book so extraordinary for its

gland, an investment firm with as distinguished a record as the House of

mental largeness of generalization, an American Buddha, that I must send

it

Rothschild in France. He served not only as treasurer of the Boston Athe-

to you, and pray you look it over if you have it not. It is called Leaves of

naum, an exclusive subscription library, but was appointed treasurer of Har-

Grass." Some years earlier Ward had tried his hand at poetry, and had had

vard in 1830, a post he held for twelve years. That there was then a marked

four poems published in the first issue of the Dial, one of them on a painting

division between the social and the intellectual upper class of the area is well

by Washington Allston.8 Emerson later had included three of Ward's poems

implied by Thomas Ward's condescending attitude towards what one might

in his anthology Parnassus. But Ward's bent was always to be artistic, not

think would have been a great honor: "The College treasurership gives me

literary. In this regard he was considerably more sophisticated than Emer-

little trouble, and is an agreeable relaxation at times and brings me among a

son or other members of his circle. Characteristically, Ward, who had spent

class of men who are educated and highly intellectual whenever I have the

a Wanderjahr in Europe visiting centers of art after graduating from Har-

time and inclination to be with them.' The son, Samuel Gray Ward, was

vard in 1836, understood with grace Emerson's shortcoming in this respect.

conscious of the gulf between the two halves of the Boston upper class, but

He excused it on the grounds that there were few influences around Emer-

considerably more sensitive. He had taken a course while at Harvard from

son to aid him in aesthetic training, that a great man is never great on all

George Ticknor, whom he admired, but whom he noticed was ostracized in

sides, and that Emerson in fact did understand the "relation of art to thought"

Boston society in later years, though Ticknor was from a prominent Boston

better than many painters.

family. Ward was not sure of the reasons for the coldness towards Ticknor,

Nevertheless there was a central divergence in how the two approached

but wrote: "It was in its way as curious an example of the prejudices of

culture. For Emerson, everything of course revolved around the potential of

my beloved native city at the conservative end of the scale as the non-

the individual: "In all my lectures, I have taught one doctrine; namely the

acceptance of Margaret Fuller and Emerson at the other."

infinitude of the private man." 10 That doctrine, here expressed just when

Here is Ward showing his fine judgment and sense of fairness, and an un-

Emerson and Ward were becoming acquainted, never changed. It was not

derstanding of Boston society while part of it. He was always a man of de-

suitable for Ward, either for his exterior or interior life. Ward was more

cency and balance. His interest in Emerson had begun because of mutual

modest about the potentials for self-knowledge and knowledge of others:

friends, especially Margaret Fuller, but it soon grew because of what each

"Myself I do not know, my friend I do not know, but the relations between

saw in the other as stimulating. Ward's portrait will now be composed, from

us I do know, and it is the only thing I know." Ward applied this view con-

three elements: cultural interests, business activities, and social position,

sistently to the nature and uses of art. In an unpublished statement titled

the foundation for the other two.

"Idealism and Realism," he concluded that human relations are the "subject

From his letters to Ward, it is clear that Emerson would have been grati-

of all the arts." "In the final analysis this is all there is of us; all other interests

fied had Ward developed culturally into more of a follower of the Ideal than

are of value only as they subserve this." Having

this

view,

it

is

not

surpris-

he ever did. Ward always showed respect for Emerson, but his own roots

ing that Ward had much less confidence than did Emerson that creative in-

302

Studies in the American Renaissance 1984

The Emerson-Ward Friendship

303

spiration could be found in nature. His studies of European paintings both

example, it would be difficult to picture Emerson reading aloud stories of

in copies at the Boston Athenxum and later in Europe led him to desire the

Boccaccio to his assembled family, but that is what Ward did with wife and

human impress on nature that European landscapes provided as America's

parents assembled in the Park Street town house. 19 In fact, Ward's first

criti-

did not. In an article on Hiram Powers' statue of a female Greek Slave (1847),

cal essay had been a defense of Boccaccio's writing. 20 Ward foresaw the

de-

he explained that nature was no longer a rich source of inspiration for any of

bilitating influence of the genteel outlook, predicting that Boccaccio would

the arts. 13 With perception he complained that for poetry "all nature has

not become more popular, "for the world grows more and more delicate as

been ransacked" and that "the vocabulary being once adjusted, and the gen-

it grows older, and Boccace is nature itself, and the most unclad nature

eral tone of thought and sentiment prescribed, making poetry has become so

withal." Sounding again more like Whitman than Emerson, Ward praised

easy that it is done as a matter of course." In a customary touch of generosity,

Boccaccio for his largeness of spirit, for finding in however low a condition of

which allowed Emerson himself to be exempt from censure, Ward added

human experience something of value. "Manliness, tenderness, nobleness,

that despite a "false theory," the leaders of this school had been "good men"

simplicity, nature, I find in Boccaccio." For over-refined moderns, a return

who have "done good work in their time."14

to Boccaccio, a "true painter of man, the creature of passion and circum-

Here Ward also indirectly challenged the Emersonian assumption that

stance," is a refreshment, moderns who are "so busy in adjusting the drap-

the individual consciousness was sufficient in the arts when he complained

ery of feeling that the bone and sinew it should cover are well nigh forgot-

that the American viewer of art asked but one question, How does this please

ten."2 On the subject of morality in art, Ward had here first laid down a

me? when his taste may be corrupted and his feeling "may demand some-

principle:

thing false and exaggerated.' 13 Nobody, he continued, wants to take the time

to learn from and admire a work of art; criticism is always hasty. Elsewhere

When we see a picture or statue, on what is our judgement of it to be founded?

he scores the tendency to praise American works: "Grave men gravely vaunt

We look to see if the sentiment is true to nature, if the drawing is correct, if the

American productions in a way that to an uninterested observer, must seem

nature is beautiful and true, if the spirit in which it is conceived be refined, and

sadly absurd." 16 Ward's recognition of the need for relationships in cultural

if we find these we are satisfied. But do we ask ourselves, when we see a drunken

matters as in social is one that moves him closer to Whitman's than to Emer-

and sensual form carved in Parian stone, whether the subject is moral, whether

it is decent? Thank heaven! I believe not naturally

when a Michelangelo

son's perspective. "It is the greater or less certainty of an audience, and the

carves a Bacchus (and his was no ideal Bacchus, but the deity of drunkenness)

nature of that audience, which rule the forms of literature, and develop or

do we ask such a question? Never. The art is its own reason. We recognize the

suppress the poems of the poet," he maintained, adding that while the great

presence of a wider law than that of our conventions and, self-forgetful, are lost

artist will write for all time and any audience, the nature of the immediate

in the power of design. We recognize in the artist, not a law-giver to man but a

audience will be a shaping force.17 Yet with a conservative bent and a keen

seer of the law of God. 4

sense of the history of the arts, he here scored the contemporary fashion to

turn out formless "pieces" of poetry, unwilling to see, as did Emerson, that

By contrast, Emerson's bias towards reading both nature and art for moral

for good reasons the modern spirit must shed the old forms.

direction is evident in much of his writing, none more obvious than here:

Ward's inspiration for art came to be Goethe, and he was indebted to

"You may chide sculpture or drawing, if you will, as you may rail at orchards

Emerson for his encouragement to undertake an important translation of

and cornfields; but I find the grand style in sculpture as admonitory and pro-

Goethe's art criticism which he completed while living the life of a gentle-

voking to good life as Marcus Antoninus. I was in the Atheneum, and looked

man farmer in the Berkshires. Goethe was a point of real contact for the

at the Apollo, and saw that he did not drink much port wine."

interests of Emerson and Ward, but he was much less a Romantic critic than

Ward also saw dangers in using art metaphorically. In his most original

Emerson or Fuller, who scolded him for his worldliness, might have liked.

article, on architecture, which contained many of the same notions expressed

Ward had approached his translation of Goethe not as a creative or inter-

by Horatio Greenough (whom he had met in Europe), Ward struck for sim-

pretive task, but as one whose obligation it was to be classically correct in

plicity and purity of form in buildings and monuments. Meanings and sym-

respect to the original.

bols were wearisome: "all sentimental monuments are bad and all conceits of

There was another even more powerful divergence on art: Emerson saw

every sort; as, a broken column, a mother weeping over her child, a watchful

it through the lenses of morality, as indeed he saw all aspects of culture,

dog, etc. They strike at first, but the mind wearies to death of them the mo-

whereas Ward had freed himself from this side of his Puritan heritage. For

ment

they

are

repeated."

Emerson might have agreed with Ward in that

304

Studies in the American Renaissance 1984

The Emerson-Ward Friendship

305

view, but he was far more prone to see art as the manifestation of idea rather

cisely the time when Emerson's influence on him was strongest, Ward be-

than as something expressing a natural condition, and with his Puritan back-

came SO restless that he had defected in the other direction, proposing to his

ground the idea often was connected to behavior. The process was intel-

father to go out to the Berkshires and establish himself as a sort of Emerso-

lectual, self-generating. Emerson defining all art as "the conscious utterance

nian American Scholar, Man on the Farm. He had begun an elaborate expla-

of thought, by speech or action, to any end,' seems generous,

but

the

nation for this shift to his father, who held the pursestrings, by stating that

thought to be uttered was, in practice, to be filtered through only the high-

except for the need to provide handsomely for a wife used to the best, which

est mind using the highest moral principles.

he wrongly believed a Berkshire farm would provide, he never would have

A second aspect of Ward's personality, his business and financial side, re-

entered business: "Long before I entered into trade, I had a disinclination

moves him even more from Emerson's idealism, as would be expected. But

for its pursuits. From a very early period, I looked upon myself as a student

Ward did not give up interest in the arts. His life pattern had more of a unity

and literary man, and so far as I had planned at all my views of life were of

to it, more of a balance between the intellectual and the workaday, than did

this complexion;

30 So much for the stability of a young man's plans.

Emerson's. As late as the 1890s he was alert to new trends and new writers.

The need for money five years later, when children had begun to arrive and

He characterized Emily Dickinson with the penetrating phrase, "the articu-

his wife's high social standards made more income imperative, coupled with

late inarticulate" in a letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson that Higginson

the opportunity to free himself from dependence on his father, meant that

said was the best critique of her work he had seen. 28 But most of Ward's

cul-

Ward would have been foolish not to seize the opportunity Baring Brothers

tural activity continued to center on the fine arts. He kept to his habit of

offered him. Moreoever, Ward had within himself a cluster of the necessary

sketching, especially landscapes. He developed a friendship with the Har-

attributes for being a successful financial agent as Joshua Bates, from Salem

vard art professor Charles Eliot Norton, and carried on an interesting ex-

like the Wards, and then high in the directorship when he interviewed Ward,

change with him on how to increase America's sophistication in the fine arts

must have sensed. It helped of course that Ward's father had been the agent,

through the public schools. And, after his relocation in New York following

but the appointment of the son was no mere act of nepotism. In the years to

the Civil War, a move he welcomed, he joined with other businessmen in

follow it turned out that Ward performed the firm's duties even more ably

founding the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Ward had, nevertheless, turned

than had his father. His trust and affability, his coolness under pressure, and

away years before from a life modelled somewhat on Emerson's contempla-

an innate knack for wise mercantile decisions combined to help both Baring

tive life. It was clear that the older man had hoped he would join him, too;

Brothers and his own fortunes prosper. He became a wealthy man in his own

his annoyance at Ward's defection was expressed in a letter to Elizabeth

right. And if most of his attentions had now to be given to business matters,

Hoar in 1849 when he remarked that Ward was "very happy in his new posi-

as he seemed to think they could have been given to studies before, he

tion, which he justifies." But Emerson's good nature could not desert him

maintained his interest in the latter and became an important steward of

for long, and their relationship, though diminished by a key change in Ward's

culture.

life, continued.

Like others of the Puritan experiment lucky enough to become wealthy

This change was that Ward was chosen to succeed his father as American

and well situated, Ward felt an obligation to support those who were at-

agent for Baring Brothers, the English investment firm. By that time (May

tempting to improve society or themselves. His generosity, which will here

1849), Ward and his beautiful wife, Anna Barker Ward, had established

be only sampled, was impressive and Emerson himself was a recipient. After

themselves in the social life of Lenox, Massachusetts, where they had

Emerson's home was partially destroyed by fire, Ward contributed $500 to a

bought, with Ward's father's help, an elegant farm whose soil Ward himself

fund for its restoration, as much as anyone. 31 Ward acted as part-time busi-

had learned to work, though "Highwood," as they called it, was by no means

ness consultant to Emerson, too, and was put in charge of the investment

self-sustaining. Anna, raised to enjoy an active and intricate social life, was

fund Emerson and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow had set up for the indigent

extremely disappointed at the change and at having to sell the place in mov-

Bronson Alcott. He responded twice when Emerson asked him to contribute

ing back to Boston. But Ward, for all his enthusiasm as a gentleman farmer,

to a fund for Thomas Carlyle, giving the amounts requested. His patience

seemed to readjust with little difficulty to a role common to all Ward males

with and generosity to the poet Ellery Channing, whom he introduced to

for generations. His marriage in 1840 had been followed by three years of

Emerson, and who seems to have lived off the cultural and financial savings

desultory brokerage work in Boston, while living in fashionable Louisburg

of others, was very great. Channing, who married Margaret Fuller's younger

Square, thanks to his father's financial help. Under this routine, and at pre-

sister, did have the decency to acknowledge one instance of charity, writing

306

Studies in the American Renaissance 1984

The Emerson-Ward Friendship

307

Ward that his gift of $200 had saved him from bankruptcy. 32 Louis

Agassiz

and social grace more alluring than Fuller's mental stimulation; he wrote his

poured out a tale of woe to Ward about his difficulties in financing his new

father that he had seriously fallen in love with Anna.4 Anna's lineage was at

museum at Harvard, and Ward responded with a check for $1,200 which

least as impressive as Fuller's. Her father was a prominent and very pros-

Agassiz expected would relieve him "of all anxiety for years to come. After

perous businessman, Jacob Barker, the family originally being from New

moving to New York, Ward's stewardship found wider applications. He

Bedford, Massachusetts, and related to the Folgers, Benjamin Franklin's

helped E. L. Godkin, editor of the Nation, with financial advice, for which

mother's family. Barker had early amassed a sizeable fortune. It was said that

the editor expressed gratitude. Godkin called his association with Ward

he shrugged off a loss of $50,000 reported to him on his wedding day. He

"more than forty-three years of friendship." Of all his charities and cultural

maintained homes in New York, Boston, Newport, New Orleans, and at

aids, none must have given Ward more satisfaction than his part in helping

Bloomingdale on the Hudson, at various times. One sign that religious ori-

to found the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1871 he gave a sum of money,

gins now meant little to the moneyed class was that while the Barkers were

by subscription, towards the purchase of a collection of paintings then in

Quakers, there was not the slightest sign among the Wards that this affilia-

Brussels that became the nucleus of the Museum's first holdings, and him-

tion mattered. Nor did it matter to her husband later when Anna became so

self went to Brussels to view the collection with the Museum's first presi-

interested in the ecclesiastical antithesis of her own sect that she joined the

dent, John Taylor Johnston, and trustee William J. Hoppin. Ward had been

Catholic church and remained in it actively, bringing up their children, all of

one of fifty citizens appointed to look into the founding of the Museum in

whom married Catholics, in that faith. But it did matter to Emerson, on

1869, and had been elected the first treasurer, serving in 1870-71. For the

whom Anna had made a great impression, as will be shown later: "I grieve

next eight years he served as a trustee. This entire pattern of cultural stew-

that she has flung herself into the Church of Rome. She was born for social

ardship was consistent with his own interests and associations, and blended

grace, and that faith makes such carnage of social relations!" 43

practical help with advice and encouragement.

The social gulf between Ward and Emerson was always very wide. Types

So much for Ward's business life and his patronage of the arts. The third

and places of residence were an indicator. While Emerson's home in Con-

element of his life's composition, running through the others, was his being

cord was spacious, even elegant, and while he was always affluent enough to

nurtured within the leading social class in Boston. It is easy to misread the

keep servants, the Wards' addresses and domiciles always bespoke social

social behavior of this group because of its Puritan origins. By the mid-

leadership. The Park Street townhouse, opposite Boston Common, the

nineteenth century it was acting in some ways more Cavalier than Puritan,

Louisburg Square apartment that newlyweds Samuel and Anna were given

as a knowledge of the social pattern of Ward's family shows. A few tart obser-

by Ward's father, the Commonwealth Avenue townhouse built by the Sam-

vations of Ward's sister Martha to her father may illustrate, though perhaps

uel Wards as soon as Back Bay had been filled in, the two Berkshire country

distorting unfavorably. From the Wards' vacation home in fashionable Nahant

residences, and the Ward's Fifth Avenue New York address after the Civil

on the north shore of Boston she wrote one summer that the social season

War-all reflected a financial and social level Emerson had no desire or

was so dull that "even scandal wearies." She wondered why the young ladies

chance to aspire to.

didn't get headaches more often, "they eat SO much and do so little." The

The first Berkshire location, later to become the site of the land adjacent

affluence of her circle is shown by an anecdote she recounts about the Jack-

to the Tanglewood music center, was a place the newlywed Wards greatly

sons, a prominent family, told to her by one of them. A young man of the

enjoyed, Ward partly for the challenge of establishing his financial indepen-

family was asked if he had ever been in England. No, he replied, but his

dence (which he could not do), Anna for the brisk social life she and her hus-

father had promised to bring him there and, if he liked it, he would buy it for

band immediately found themselves in the middle of. The Wards hosted par-

him.38 A couple's engagement brought forth this response from Martha: "I

ties to which fifty or sixty came; they had come to the Berkshires with a

should think it a very good match-he wants a dashing wife, and she wants

complete social entrée, in particular to Charles Sedgewick, then the area's

money."

social leader, who came to admire the Wards. Sedgewick played a role in the

Ward's own choice of wife reflected the power of his social heritage. He

Berkshires roughly parallel to that of Emerson in Concord, except that the

had had ample opportunity to be drawn to an intellectual woman in his

composition and activities of the social groups differed much. During the

friendship with Margaret Fuller, who at one point seems to have been ready

five years they were there (1844-49), Emerson hinted to the Wards that

to turn things into more than friendship. 40 But on a trip to New Orleans on

he would enjoy visiting them; but it is well that he never did. Probably he

business for his father in 1839, he had found Anna Hazard Barker's beauty

sensed that he would have been out place. Berkshire County was gregari-

308

Studies in the American Renaissance 1984

The Emerson-Ward Friendship

309

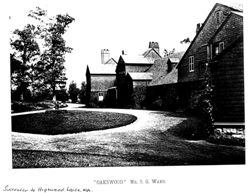

ous, busy, expensive, elegant, very social. The second Berkshire residence,

in Washington, D.C., when Ward was seventy-two and in retirement; he

Oakwood, which Ward built himself as a retirement home, was designed by

wrote back to Boston that his host was "wonderfully young and like his for-

the distinguished Boston architectural firm of McKim, Mead, and White; for

mer self.

and his interest in good things is as lively as ever." Ward's

his wife Ward had a Catholic chapel built on the grounds.

social position had nurtured and steered him well all through his life.

It was Ward's general approach to life, above all, especially after the Civil

It is now possible to turn back to Emerson and pick up the story of his

War when he had moved to New York, that shows him as much more cos-

approach to Ward and Ward's circle, a story that illustrates Emerson's con-

mopolitan and Cavalier than Emerson. When Emerson wrote what was

to

stant mediating between the ideal and the real.

be the last personal letter to the Wards in 1866, in thanks for a picture of

Emerson's views on Boston society walked a narrow line. He was not nearly

themselves, he reminded them that "our intercourse with our friends (I

as comfortable with it as had been his father, whose church depended on it.

mean the tone of it), is sometimes no measure of our real delight in them."

Yet he was not ready to reject it outright. Within two years of meeting Ward

While the picture presented a serious image, Emerson added that such a

he had published the first series of Essays (1841), among which was "Man-

seriousness was more "becoming" to one who knew how to spend each day

ners." In the third paragraph of that essay he had gone to much trouble to

well "than any lights which wit or gaiety might lend to other hours." But by

distinguish between the superficial idea of a gentleman and a deeper one.

using this flattery, Emerson misjudged the usual stance Ward took, at least

The latter must retain the heroic element, and rid itself of the idea of fash-

the Ward of the years after 1850 when he began devoting his life to business.

ion, "a word of narrow and often sinister meaning." The true gentleman, in-

Business and an elegant social style were then naturally linked.

dependent, able to meet all classes of men on his own terms in noble ac-

Ward's wife is said to have remarked about her husband in later years that

cents, is a rare person, Emerson admits. Manners do have their place, as

when she first knew him when he was about twenty-one, he seemed pre-

does fashion, but only if they are the outward manifestation of inner charac-

maturely old, but that "he grew young, and has been growing younger ever

ter. Such a view is traditionally Puritan. Social frivolity and play-acting with

since. Such may have been more than a happy wife's tribute. Ward took

one's personality are inadmissable. Public reputations don't matter. Degree

much care with what he ate and what he wore. He once wrote out his views

of wealth is immaterial.

on

dress and its importance.47 Among advice he set down was that "every

Emerson once recorded in his journal that most aristocrats are "trifling

day" should be considered "more or less a jour de fete." Referring to Goethe's

and tedious company." But he singled out Ward himself for exception:

approval of the role of appearance, he stated that proper dress is the most

"Ward has aristocratic position and turns it to excellent account, the only

universal "if the most superficial" entrée into all human societies, the letter

aristocrat who does. 49 Yet Emerson could occasionally give in to the lure of

of introduction "to all strangers and women," and "part of politeness and the

the more obvious social graces: "Your name is forever commended to your

desire to please." Ward's stress on human relations, always stronger than

ear after it has been spoken by a man like Otis or a woman like Anna Bar-

Emerson's, comes across in this document especially when he says: "Dress is

ker." The man was Harrison Gray Otis, a prominent society gadabout. The

part of the freemasonry of intercourse by which we slide into relations that

woman was Anna Hazard Barker, known in Boston, Newport, and New Or-

must otherwise be taken by storm, if taken at all." Ward also delighted in

leans for her beauty and social graces, and the woman Ward was to marry a

gourmet food, as he seems to have put some store by the fashionable The

few weeks after Emerson named her here. In fact, for Anna Barker, Emer-

Physiology of Taste by Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin (1854).

son worked up an enthusiasm that conveniently united his ideals about char-

The Wards had a circle of friends large, varied, and distinguished. They

acter to the realities of her manners. Here was a woman that could stimulate

entertained often and kept up with many, as their correspondence between

as no Margaret Fuller could stimulate. After a few meetings with her he

1850 and 1875 attests, peppered with thank-you notes and brief social letters

wrote that her "miracle" was first the "amount" of her life and then the de-

to and from those known as much for cultural as for social distinction. The

gree of "intimacy" she could call forth: "The moment she fastens her eyes on

network of relations was intricate and solid, as a sampling of correspondents'

you, her unique gentleness unbars all doors, and with such easy and frolic

names will attest: Edward Everett, George William Curtis, Thomas Baring

sway she advances and advances and advances on you, with that one look,

(from England), Jared Sparks, Richard Cobden, Richard Henry Dana, Wil-

that no brother or sister or father or mother or life-long acquaintance ever

liam Morris, John LaFarge, John Chandler Bancroft, Celia Thaxter, Wil-

seemed to arrive quite so near as this now first seen maiden." He could not

liam T. Blodgett, Henry James, Jr. Ward was able to handle his later years

believe he had seen her only a few times: "I should think I had lived with her

youthfully, much as his wife had suggested. James Russell Lowell visited him

in

the

houses of eternity.' Here is Emerson bordering on the Cavalier.

310

Studies in the American Renaissance 1984

The Emerson-Ward Friendship

311

Moreover, to write such sentiments to another single young woman shows

in the shaping of his ideals or the capturing of his loyalties. When the inten-

Emerson's social naivete, and perhaps also his unwillingness to acknowledge

sity of his connections to Ward and Anna Barker had subsided, he was able

the sexual ingredient in attractiveness. His first journal entry on Anna Bar-

to find his balance again. Though the lure the other way was sometimes

ker had stressed that socially she was not of his class but of a higher, showing

strong, the scales were to tip in the direction of cultivation of the ideal, and

his acknowledgement of social realities beyond what might have been ex-

of the self and friends closer to home: "-in reading Legere's journal, who

pected. But she had dealt "nobly" with all. Her conversation was the "frank-

seems to have seen the best company, I find myself interested that Ward

est" he had ever heard; "She can afford to be sincere," he had continued,

should play the part of the American gentleman well, but am contented that

"the wind is not purer than she." He was willing to make allowances for

he should do that instead of me-do the etiquette instead of me-as I am

superficial social aspects more in women than in men, as when describing

contented that others should sail the ships and work the spindles." ST

another young woman of high class: "Miss Forbes gratified me very much in

While Emerson did mainly separate himself from high society, then, by

precisely the way I hoped. I delight in a lady, in the rare woman in whom

origins, proximity, and more than might be expected, by inclination, he

what talent, what genius they have, runs to manners. Again one may

came in spirit quite close to it. His ideals by no means squared with certain

question Emerson's tact in writing such a sentiment to a young woman, es-

aspects of it, but special kinds of real people were something else.

pecially to Margaret Fuller. As to Ward and Anna Barker, Emerson had be-

In this connection there was a noticeable difference in how Emerson and

come so impressed with both that he took the trouble to attend their wed-

Ward responded to unfamiliar groups in America. Ward had taken a western

ding on 3 October 1840, at Professor John Farrar's home in Cambridge,

and southern tour of America shortly after his year in Europe, and recorded

where Ward had boarded in college. "Farewell, my brother, my sister!" he

his impressions richly in a series of letters home to Park Street. The letters

had written them theatrically shortly before.5 A society wedding was a rare

are brimming with enthusiasm for evidences he found of American ingenu-

kind of event for Emerson to attend.

ity, of the hospitality of frontier families, the enterprise of western farmers.

Yet Ward as aristocrat was impressing Emerson more and more since their

Not once does it appear that he is patronizing these people, as might be ex-

meeting in 1838. By 1843 he was using superlatives to Carlyle: Ward was

pected from one of his class and section. Instead, he entered into the spirit of

"my friend and the best man in the city, and, besides all his personal merits,

the places he visited with youthful gusto and great adaptability, aided much

a master of all the offices of hospitality." Two years later he expressed

to

to be sure by carrying letters of introduction to leading citizens. Even in

another correspondent the same kind of admiration in even more glowing

small towns he maintained this tone: "In coming to one of these country

terms:

towns if you have any claim upon anybody you are received by open arms by

the whole city, and though I was only one day in Huntsville, I saw as many

Sam Ward came to see me on Monday and spent a night here. I was never so

people and things as I could have shown a stranger in Boston in a week."

much impressed by the finished beauty of that person. He was a picture to look

By contrast Emerson has left behind a meagre record of people and places

at as he sat, and his conversation was the most solid, graceful, well-formed, and

visited on his numerous western lecturing jaunts. Nowhere does a sense of

elevated by his just sentiment. What sincere refinement! What a master in life!

the realities of American cities and towns take precedence over other matters,

For his talk for the most part was of his new purchased farm [in the Berkshires],

usually intellectual, recorded in letters and journal entries. Only in one

of the house and buildings he is to raise, of his village neighbors, and of Massa-

piece of writing, English Traits, does he exercise what is shown to be a re-

chusetts and American politics. I compare this man, who is a performance, with

markable talent for assessing the character of a country. Why he did not do

others who seem to me only the prayers. How easily he rejects things he does

SO with his own is puzzling, in view of his life-long preference for locating

not want, and never has a weak look or word. He recommends by his facility and

America's identity at home rather than across the seas. The best explanation

fluency in it the existing world and society and Alcott and Fourier will find it the

harder to batter it down. I found myself much warped from my own perpen-

may be that he was too caught up in propagating his ideals. The message of

dicular and grown avaricious overnight of money and lands and buildings, after

self-reliance for his countrymen was so obsessive that the realities of his na-

hearing this fine seigneur discourse so captivatingly of chateaux, gardens and

tive surroundings and the precise nature of the common lives around him

collections of art. 5

were neglected. When the focus is narrowed even more from social class

to the two men, Emerson's habit of alternating between theory and reality,

But this was as far as Emerson would ever go in allowing the ways of wealth

between what might be and what is, shows its strength. He found both simi-

and society to challenge eccentrics like Bronson Alcott and Henry Thoreau

larities and contrasts useful as he thought about Ward and the subject of

312

Studies in the American Renaissance 1984

The Emerson-Ward Friendship

313

friendship during the early 1840s. "The most arresting people," he recorded

journal less in terms of intellect than of personalities when he wrote Fuller:

in his journal in 1841, "are those who have genius by accident and are power-

"We wish not to multiply books but to report life, and our resources are

ful obliquely," adding in reference to Ward: "Beautiful to me among SO many

therefore not SO much the pens of practical writers as the discourse of the

mediocre youths as I see, was Sam Ward when I first fairly encountered him,

living and the portfolios which friendship has opened to Emerson may

and

in

this

way

just

named."

Here is no suggestion of social class whatever.

well have been thinking of Ward's portfolio and Ward's friendship.

Ward's quality, he told himself, was entirely innate, and his "genius" was his

In May he wrote John Sterling in England, whom he had never met, that

fascination. The idealism comes through even stronger once he began writ-

he was a worshipper of friendship and could not find "any other good equal

ing Ward:

to

To Fuller he wrote about Caroline Sturgis in June on the same sub-

ject, stressing through hyperbole the slow ripening that true friendship

You and I, my friend, sit in different houses, and speak all day to different per-

needed. "We are beginning to be acquainted and by the century after next

sons, but the differences-make the most we can of them-are trivial; we are

shall be the best of friends. Being SO majestic cannot surely take less time to

lapped at last in the same idea, we are hurried along in the same material sys-

establish a relation. And to Ward he had written in January that discover-

tem of stars, in the same immaterial system of influences, to the same untold

ing friends "was the most attractive of all topics," a subject SO "high and sa-

ineffable goal. Let us exchange now and then a word or a look on the new phases

cred" that "we must saunter if we would find the secret." "If men are fit for

of the Dream.60

friendship," he continued, "I think they must see their mutual sympathy

across the unlikeness and even apathy of today.' Six weeks later he wrote

Emerson is seeing their friendship as a part of the interlocking Platonic rela-

him: "I find myself, maugre all my philosophy, a devout student and admirer

tionships that he conceives the universe to have wisely established for some

of persons. I cannot get used to them: they daunt and dazzle me still."7

benign purpose. Yet fifteen months earlier he had written Ward that the rea-

It is by now possible to guess what the main lines of thought in "Friend-

son he was interested in him was a matter of their differences: "-with tastes

ship," published with the first series of essays in 1841, would turn out to be.

which I also have, you have tastes and powers and corresponding circum-

As with many of his essays, the organization follows roughly the pattern nor-

stances which I have not and perhaps cannot divine."6

mally used in homiletics. Paragraphs one through five explore the health-

Originally it had been Ward's studies in art that had started the relation-

giving nature of friendship, counterpointing the ideal and the worldly as in

ship. After visits to Concord in the fall of 1838, Ward had lent Emerson a

this passage, where a reference to Ward seems possible: "Shall I not call God

portfolio of copy sketches he had gathered in Europe. He gave Emerson one

the beautiful, who daily showeth himself so to me in his gifts? I chide society,

of them, a sketch of Raphael's Endymion, for which the older man expressed

I embrace solitude, and yet I am not SO ungrateful as not to see the wise, the

strong gratitude 62 It hung on Emerson's study wall thereafter. But the fine

lovely and the noble-minded, as from time to time they pass my gate. Who

arts were only a bridge between them. Emerson had, after all, himself been

hears me, who understands me, becomes mine-a possession for all time"

to Europe and visited many of the cultural centers; nor could his interest in

(paragraph five). Paragraphs six through nine qualify this affirmation, show-

art match Ward's. Besides, there was much else on his agenda at this time.

ing how friendship, like love, can disturb and even blind the private self.

During the winter months of 1839-40, he had delivered a series of lectures,

Paragraph ten moves to balance the two sections by means of definition: the

one of which, probably the one on "Love," served as a sketch for the essay

highest kind of friendship consists of two central elements, sincerity and ten-

"Friendship." The latter, he wrote Ward on 14 July 1840, was "now into

derness. Emerson has trouble explaining what he means by tenderness. He

some shape, not yet symmetrical but approximate to that." He would send it

clearly considers it of great importance and, having found, he says, little in

to him as he had wanted to earlier.64 On 22 June he had written Ward that he

books that speak adequately to the word, returns to the old Puritan notion of

was "just finishing" the essay derived from the winter lecture, on which he

worth and purity as necessary conditions for exercising tenderness: "Can an-

would like Ward's comments, adding: "I have written nothing with more

other be so blessed and we so pure that we can offer him tenderness?" He

pleasure, and the piece is already indebted to you and I wish to swell my

goes no further with the subject. The long section following (paragraphs

obligations." Further, in the early spring of 1840, he was planning the

twelve through eighteen) lays down his stringent requirements and condi-

main outline of "The Over-Soul," and wrote Fuller on 15 April that it was

tions for achieving the ideal friendship. For example: "The condition which

almost complete. He was also involved with long-delayed plans for publica-

high friendship demands is ability to do without it. That high office requires

tion of the Dial, the first number appearing in July. He thought of the new

great and sublime parts. There must be very two, before there can be very

314

Studies in the American Renaissance 1984

The Emerson-Ward Friendship

315

one. Let it be an alliance of two large, formidable natures, mutually beheld,

love." When it comes to choosing, his solace is not instrumental but a further

mutually feared, before yet they recognize the deep identity which, beneath

flight of the imaginative ideal.

these disparities, unites them" (paragraph sixteen). The conclusion (para-

The dichotomy of ideal and real is even more evident in the cluster of

graphs nineteen through twenty-two) admits to the rarity of the ideal friend-

letters, earlier referred to, that Emerson wrote Ward between 1838 and

ship, and circles back to the second section in which was stressed the protec-

1853 collected and published in 1883 by Charles Eliot Norton, professor of

tion of the private self, leaving the subject in a condition of some ambiguity.

art at Harvard. 72 Emerson's interest in Ward depended on Ward's combining

Much of what Emerson is saying in "Friendship" could be referring to his

the two polarities of dream or hope, and worldly effectiveness. Also central

current relations with Ward, though there is no way of making precise con-

to Ward's attraction was his active intelligence, for it was intelligence, in the

nections. Probably the essay was indebted to a number of his associates at

form of a lively imagination, that drew Emerson to those he called friends.

the time, especially as he also says in the essay that he pleases his imagina-

Where he found none he quickly lost interest. His enshrining of a particular

tion "with a circle of god-like men and women variously related to each

kind of intellect, the kind one would expect from a Romantic, in common

other and between whom subsists a lofty intelligence" (paragraph fourteen).

with such writers as William Wordsworth or Carlyle, presented him with a

Despite his thinking in terms of numbers occasionally, parallels show that

major dilemma that he never resolved, if indeed he was conscious of it.

Emerson's friendship with Ward was typological, that it could stand for any

Emerson was seeking to propagate a national creed through the regenera-

friendship so long as it was of the highest sort.

tion of the private self, but a regeneration depending on the imaginative ac-

Nevertheless, certain ideas in the essay point more closely to Ward. A

tivity of the mind. This activity is not something that can be implanted in

"rare and costly" nature is essential, "each so well tempered and SO happily

anybody from the outside. According to Romantic assumptions it is a gift, an

adapted, and withal so circumstanced [he appears to be referring to eco-

innate capacity that could rescue men from being the pawns of experience in

nomic security and comfort] as to allow for the highest sort of meetings"

a Lockean world. To his credit Emerson in his Americanism wanted to

(paragraph fourteen). Also needed is a rare mixture between "likeness and

extend his vision to all: "The perfect world exists to every the poor-

unlikeness": "the only joy I have in his being mine, is that the not mine is

est drover in the mountains, the poorest laborer in his ditch. Quite indepen-

mine. I hate, where I looked for a manly furtherance or at least a manly resis-

dent of his work are his endowments. There is enough in him (grant him

tance, to find a mush of concession" (paragraph sixteen). Further, a friend

capable of thought and virtue) to puzzle and outwit all our philosophy." But

must act magnanimously: "Friendship demands a religious treatment"; rev-

the qualification about the need of having thought and virtue gives his posi-

erence is essential (paragraph seventeen). "Treat your friend as a spectacle."

tion away. Can most men practice virtue when it depends on the exercise of

We should not get too close to a friend, meeting his relatives and going to his

rigorous imaginative thought? Why should the practice of virtue depend SO

home and he to yours too often: "Leave this touching and clawing. Let him

heavily on the use of the mind? Emerson was too decent a man ever to pa-

be to me a spirit" (paragraph eighteen). A letter from one to the other may

tronize those whose weaker attributes left them outside the circle of saint-

be enough. Do not hurry the process of making friends, which is largely un-

hood or friendship, but the fact is he never did or could make close contact

conscious and mysterious: "Let us be silent-so we may hear the whisper of

with any but those with special intellectual powers, whether found in the

the gods" (paragraph twenty). We must be perfectly self-possessed before-

maverick intelligentsia such as Alcott, Jones Very, Fuller, and Thoreau, or

hand. Emerson's inveterate habit of idealizing and symbolizing may have

among more worldly and social types such as Ward. The reason he could not

here used Ward's friendship for its exercise: "There can never be deep peace

was philosophical as well as temperamental. While his generous spirit fre-

between two spirits, never mutual respect, until their dialogue each stands

quently called attention to this failure to warm up to people, his own princi-

for the whole world" (paragraph nineteen).

ples pulled him away from them anyway. They kept him from fashioning a

Yet he had checked his idealism in this essay, too. He had starkly recog-

reasonable unity of thought and experience, and unity was a central philo-

nized the difficulties of actual friendship: "We walk alone in the world.

sophical need of Emerson. He relied instead on that highly American solu-

Friends such as we desire are dreams and fables" (paragraph twenty). With

tion, a tone of hope and a trust in the future. He begged the question.

characteristic good nature he added: "But a sublime hope cheers ever the

With Ward, nevertheless, there was the present. In Puritan style, Emer-

faithful heart, that elsewhere, in other regions of the universal power, souls

son saw him as representative. Writing to Ward in 1848 on shipboard as he

are now acting, enduring and daring, which can love us and which we can

returned from England, and striking a curiously apologetic note, he ex-

316

Studies in the American Renaissance 1984

The Emerson-Ward Friendship

317

pressed this kind of interest in him: "What is it or can it be to you that through

the social amenities, their friendship blooming in the early 1840s and con-

the long mottled trivial years a dreaming brother cherishes in a corner some

tinuing strongly for about ten years, then diminishing after Ward joined the

picture of you as a type or nucleus of happier visions and a freer life?" He

business ranks. In 1838 Emerson had stressed the importance of the social

reassures Ward that if his abilities fail to measure up it will not matter: "It is

graces when he described kindness as "elegant" and "never vulgar." 77

He

with good reasons that I rejoice in the token." He then reflects on what he

explained in the introduction to his lecture series "Human Culture" that he

tacitly admits is the paradox of the ideal and the real: "Strange that what is

might join the idea of the "adoration of justice" to "the elegant accomplish-

most real and cordial in existence should lie under what is most fantastic and

ments of the gentleman." It seems clear that Emerson's friendship with

vanishing. I have long ago found that we belong to our life, not that it be-

Ward, always by birth and training the prototype of the best gentility, must

longs to us, and that we must be content to play a sort of admiring and sec-

have been sustained by the worldly and social as well as by Emerson's vision

ondary

part

to

our genius.' Such flights of rhetoric intermingle with more

of the ideal.

mundane references in the correspondence, but the thrust is definitely in

Emerson's letters to Ward, while telling much about Emerson's effort to

favor of the former. Ward was, like certain other young people, a kind of

fix his thinking on friendship as an ideal, also show something about this

hostage for Emerson's dream of what America might become. He turned out

closer, more personal side of their relation. A common interest in art was

not to fulfill Emerson's hopes for him, showing that the Boston world of

only a bridge between them. Emerson was soon listening to Ward's mel-

intellect and the Boston world of business and society remained two worlds.

ancholy restlessness, probably about career choices, which, however, he

It was only Emerson's good nature that allowed him to accept Ward's apos-

turned aside:

tacy in leaving his group to follow his father as American agent for Baring

Brothers.

But I will not understand an expression of sadness in your letter as anything but

Ward had come to Emerson well recommended, and well equipped intel-

a momentary shade. For I conceive of you as allied on every side to what is

lectually. Under no financial strain, as Emerson had been while there, he

beautiful and inspiring, with noblest purposes in life and with powers to execute

was graduated from Harvard in 1836 where he had sat, by the accident of

your thought. What space can be allowed you for a moment's despondency? The

alphabetical listing, next to the strange Jones Very in class after class. Yet the

free and the true, the few who conceive of a better life, are always the soul of

two remained strangers; Ward as worldly and normal as Very, whom Emer-

the world.79

son also admired, was transcendental and peculiar, the two the polar ex-

tremes of those to whom Emerson was attracted. It had been in the summer

Such idealizing must have been cold comfort to Ward. Also troubling may

of 1838 that Fuller had spoken to Emerson with enthusiasm about Ward,

have been Emerson's disparaging reference to business life in the same letter,

whom she described as being sophisticated about European art. She also

since Ward knew that all other influences pointed him to a life of finance.

must have recommended Ward as good company, too, since she had already

The concept of the saving remnant, a Puritan legacy running counter to the

found him so. Emerson invited Ward to Concord for a weekend, and Ward

expansive ideals of Transcendentalism, is also given explicit voice in this

had made the trip from his elegant Park Street home in Boston. 75 Boston and

letter: "With a few friends who can yield us the luxury of sincerity and of a

Boston gentry were not strange to Emerson, of course, since his first thirty-

manly resistance too, one can face with more courage the battle of every

one years had been spent there; his congregation of the Second Church, his

day-and these friends, it is a part of my creed, we always find; the spirit

father's Boston church, was not economically or socially much different from

provides for itself" (pp. 16-17). Such an aspect of his creed would tend to

those people he would later encounter in Concord, also a location where he

create coteries, as indeed it did, rather than to improve the world. Ward's

had roots. The sense of being rooted was always strong in Emerson: "What

own vision of social usefulness went well beyond coteries.

are my advantages? The total New England," he had catechised himself be-

But even Emerson needed the intimacies of normal friendship to some

fore beginning a series of lectures on human culture during the winter of

degree, as his reaching out to Ward demonstrates. He began advising Ward

1837-38.76 But just as he found common people difficult or useless to ap-

on books, and Ward showed his willingess to follow the older man's lead,

proach closely, Emerson did not often find the mercantile wealthy easy or

once sending him a critique of Antigone that pleased him (p. 19). In a few

valuable to know, as has been shown. Ward was both a type in the ideal

months, characteristically, he was disparaging reading to Ward: "it is a foolish

sense and an exception in the real world of society and business.

conformity and does well for dead people" (p. 24). Clearly he was trying to

The more practical side of the relationship depended on observation of

stimulate in Ward what he called in the same letter "The old creative force."

318

Studies in the American Renaissance 1984

The Emerson-Ward Friendship

319

Meanwhile he assured him that he "had set [his] heart" on Ward's reading his

tion which every journey makes to my exaggerations, in the plain facts I get,

and in the rich amends I draw for many listless days, in the dear society of here

essay on friendship; a week later he sent it on (pp. 23, 26). Emerson must

and there a wise and great heart. I hate the details, but the whole foray into a

again have received some despondent inquiries from Ward a year and a half

city teaches me much. (pp. 51-52)

later. Again he turned them aside: "My friend shall solve his own questions,

as I suppose whoever makes a wise inquiry only announces the problem on

This is a portrait not of the serene sage of Concord but of one needing human

which he is already busy and which he will be the first to dispose of, and I

response, even reassurance. The world might need redeeming, but it must

shall gladly attend all the steps of the solution" (p. 35). 80 Here is a

logical

also be taken on its own terms, however profane, so long as one could find

extension of self-reliance, but again one may wonder how useful the ap-

here and there a kindred soul.

horism was for Ward.

As a kindred soul, Ward provided a pipeline to the practical world for

There were a few more visible and more practical signs of their close rela-

Emerson as well as a listening post when the older man sat down at his writ-

tionship in the letters. Emerson commiserates with a slight illness of Ward

ing desk in visionary moments. In other letters he shares with Ward such

(pp. 21-22). He not only recommends books but lends him some, such as St.

real topics as his townsman Samuel Hoar's moral behavior in South Carolina,

Augustine's Confessions (p. 23). He shows great warmth to Ward at the time

which he admired, a visit with Nathaniel Hawthorne to the nearby Shaker

of his engagement to Anna Barker, adding an appreciation on a personal

village, the wealth of talent among the English leaders (but their complete

level: "Your frank kindness has been a bright sign in my firmament,-

lack of imagination), and his effort to defend America from their indifference

few beams were ever so grateful" (p. 33). He is pleased to hear of the birth of

(pp. 56-58, 63, 66-70). He also reports that Thoreau "is building himself a

the Wards' first child (p. 38). But he would break out with observations, as

solitary house by Walden Pond," generously omitting that it would be on his

when in the same year (1841) he confesses to the primacy of humans over

own land.8 The final subject in this sequence of letters was worldly: his

ideas for him. Here the attraction of the confession is diminished by his mak-

effort, with Ward, to establish a social club of likeminded men, an effort that

ing moral distinctions: "I see persons whom I think the world would be

did bear fruit in the Saturday Club which met monthly in Boston for a number

richer for losing; and I see persons whose existence makes the world rich.

of years. The paradox at the heart of Emerson's position on human relations

But blessed be the Eternal Power for those whom fancy even cannot strip of

is seen in his urging that for membership they accept "the broadest demo-

beauty, and who never for a moment seem to me profane" (p. 32). He wanted

cratic basis" but also that the practice of blackballing be retained (p. 77). He

Ward to show him some sign that he was "an elector and rejector, an agent,

would have it both ways: invite all to join, but allow for exclusiveness at the

an antagonist and a commander," and urged him to send him news of real life

same time. To be sure, other clubs he belonged to did operate with such

in the city: "I wish to know how the street and the work that is done in it look

restrictions. But such was a sign of the difficulty at the heart of his hopes for

to you" (pp. 36-37). A year and a half later, from Philadelphia, he wrote

the improvement of mankind. Although every man and woman would be in-

Ward another more personal confession on how people affected him: "It

is

vited to partake of the process, few could in fact be expected to measure up.

strange how people act on me. I am not a pith ball nor raw silk, yet to human

The gap between his ideals and the real world could never close.

electricity is no piece of humanity SO sensible. I am forced to live in the

Still, Emerson did not mind. Platonic dualism joined to the principle of

country, if it were only that the streets make me desolate. Yet if I talk with a

unity provided him with a method for reading all aspects of the universe.

man of sense and kindness, I am imparadised at once" (p. 51). Further on he

These words from "Plato; or, the Philosopher" suggest the focus of his analy-

develops this theme, showing his struggle with himself in the face of realities:

sis in that essay and his way of approaching all subjects: "Oneness and other-

ness. It is impossible to speak or to think without embracing both" (para-

It is because I am so idle a member of society: because men turn me by their

graph thirteen). Comfortable with this method, he tended to move from fact

presence to wood and to stone; because I do not get the lesson of the world

towards idea, from material towards spiritual, seldom in the reverse direc-

where it is set before me, that I need more than others to run out into new

tion. Materials, facts, things, bodies, were lesser orders of being. Such

a

places and multiply my chances for observation and communion. Therefore,

whenever I get into debt, which usually happens once a year, I must make the

tendency of mind worked against his reaching out as one human to another.

plunge into this great odious river of travellers, into these cold eddies of hotels

Yet at the same time he recognized the need for balance: "Solitude is im-

and boarding houses-farther, into these dangerous precincts of charlatanism,

practicable, and society fatal. We must keep our head in the one and our

namely, lectures, that out of all the evil I may draw a little good in the correc-

hands in the other. The conditions are met if we keep our independence, yet

320

Studies in the American Renaissance 1984

The Emerson-Ward Friendship

321

do not lose our sympathy."82 In his alternating between the ideals and reali-

ever virtue is in us? We will never more think cheaply of ourselves, or of

ties of friendship, there is illustrated this same habit.

life."

Another habit was just as powerful, and that was the tendency to see all

Yet the difficulties Emerson must have always felt in his social dealings

things in terms of growth and progress. Had he been formed in the next

sprung in large measure from his impossibly high level of expectation, evi-

generation, Emerson would eagerly have embraced many (though not all) of

dent in this passage from "Character" (1844):

the social analogies possible to draw from Darwinian science. He wrote

Ward in 1841: "We are all dressed out in tendencies, and are loved or rather

If it were possible to live in right relations with men! If we could abstain from

tolerated for the hopes we awaken" (p. 38). His support of a kind of dualistic

asking anything of them, from asking their praise, or help, or pity, and content

development is suggested to Ward two years later: "Is [a man] at the same

us with compelling them through the virtue of the eldest laws! Could we not

time both flowing and fixed? Does he feel that Nature proceeds from him,

deal with a few persons-with one person-after the unwritten statutes, and

make an experiment of their efficacy? Could we not pay our friend the compli-

yet can he carry himself as if he were the meanest particle? All and nothing?"

ment of truth, of silence, of forbearing? Need we be so eager to seek him? If we

(p. 49). Emerson once used his faith in the value of growth and change as an

are related, we shall meet.

excuse for not answering Ward's worried inquiries: "Not in his goals but in

his transitions man is great, and the truest state of mind rested in becomes

Emerson knew such hopes were seldom realized. In his own relations with

false" (p. 30).

Samuel Gray Ward, as with others who interested him, he made a strong

What little Emerson had said in his 1836 essay Nature about man's rela-

effort, at least, to translate into action what he had found essential in his

tion to other men foreshadowed his later position. At the end of the section

speculations.

"Discipline" he sees the human forms, "male and female," as "the richest

informations of the power and order that lie at the heart of things." Although

every human form is "defective" (his ancestors would have called it original

NOTES

sin), the "sea of thought" awaits it as an aid and minister. In our childhood

and adolescence we have no choice but to love those who help us grow. But

when we are mature, we can choose-and if wise will choose as a friend he

1. Materials on Samuel Gray Ward and, for the most part, on Emerson's friendship with him,

are taken from my dissertation, "Puritan Aristocrat in the Age of Emerson: A Study of Samuel

who is "an object of thought." Through his character we will convert that

Gray Ward" (University of Pennsylvania, 1961), based on the following manuscript collections:

thought to our wisdom. But once that friend has so served us, we can then

Thomas Wren Ward Collection (MHi), which includes all the letters between Ward and his fam-

let him go. We will want to let him go.

ily (except as noted), as well as the diary of Thomas Wren Ward; Samuel Gray Ward Collection

Such is the chilly theoretical base for Emerson's early public thinking on

(MH), which includes letters from Emerson to Ward, many letters of a social nature to the Sam-

friendship. Its justification is that it is all for the enrichment of the self, the

uel Gray Wards, Ward's unpublished poems, and Anna Barker Ward's diary of 1845-1852; and

Ward Family Papers, collected and privately printed by Samuel Gray Ward (Boston: Merry-

potential self always being at the center of his concerns. It is consistent and

mount Press, 1900), a collection of Ward documents, the major one being Ward's "Long Letter

reasonable, but in practice nobody of decency could tolerate its egocen-

to His Grandchildren."

tricity, certainly not Emerson. Fortunately these generalizations were not

2. "Long Letter to His Grandchildren," Ward Family Papers, pp. 173-74.

the sum of his reflection on men's relations, as has been shown. And in his

3. Thomas Wren Ward to Joshua Bates, Boston, 4 September 1832.

person Emerson was by all reports a kind and gentle man to everyone. In

4. "Long Letter," p. 136.

5. Ward to Charles Eliot Norton, Washington, D.C., 3 April 1899.

"Friendship" and in his letters to Ward he called for anti in his life practiced

6. "Long Letter," p. 164.

tenderness, sincerity, loyalty, consideration, and patience. There were many

7. Emerson to Ward, Concord, 10 July 1855. This was eleven days before he wrote his famous

other places where he struck the same notes. In "The Over-Soul" (1841) he

letter of greeting to Whitman.

had called for men to find and nourish the best in themselves, not selfishly

8. "To W. Allston, On Seeing His "Bride"; see also "Come Morir," "The Shield," and "Song,"

but as Christ had done. In "The Uses of Great Men" (1850) he had stressed

Dial, 1:83, 84, 121, 123.

9. Ward to John Jay Chapman, Washington, D.C., 5 January 1899.

the more generous impulses: "There is a power in love to divine another's

10. April 1840, The Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks of Ralph Waldo Emerson, ed. Wil-

destiny better than that other can, and by heroic encouragements, hold him

liam H. Gilman, Ralph H. Orth, et al., 16 vols. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press,

to his task. What has friendship so signal as its sublime attraction to what-

1960-82), 7:342; hereafter cited as JMN.

322

Studies in the American Renaissance-1984

The Emerson-Ward Friendship

323

11. "Long Letter," p. 205.

43. Emerson to Arthur Hugh Clough, 17 May 1858, Emerson-Clough Letters, ed. Howard F.

12. This manuscript, written on notepaper in Ward's handwriting, is undated, although as

Lowry and Ralph Leslie Rusk (Cleveland: Rowfant Club, 1934), letter no. 31.

Ward mentions impressionism it is probably a late document (in the possession of Dr. Anna

44. See Richard D. Birdsall, Berkshire County (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959),

Ward Perkins). The statement reflects Goethe's central notion of the artist's need of a strong

pp. 323-38, for a complete account of Ward's role in Berkshire life.

unconscious or daemon. Ward stresses the unconscious for being the source of an artist's power

45. Emerson to Anna Barker Ward, 4 August [1866?].

if wedded to "the gift of representation." Such an approach shows his modernity. Emerson per-

46. Edward Waldo Emerson, The Early Years of the Saturday Club, 1855-1870 (Boston: