From collection Creating Acadia National Park: The George B. Dorr Research Archive of Ronald H. Epp

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

Page 62

Page 63

Page 64

Page 65

Page 66

Page 67

Page 68

Page 69

Page 70

Page 71

Page 72

Page 73

Page 74

Page 75

Page 76

Page 77

Page 78

Page 79

Page 80

Page 81

Page 82

Page 83

Page 84

Page 85

Page 86

Page 87

Page 88

Page 89

Page 90

Page 91

Page 92

Page 93

Page 94

Page 95

Page 96

Page 97

Page 98

Page 99

Page 100

Page 101

Page 102

Page 103

Page 104

Page 105

Page 106

Page 107

Page 108

Page 109

Page 110

Page 111

Page 112

Page 113

Page 114

Page 115

Page 116

Page 117

Page 118

Search

results in pages

Metadata

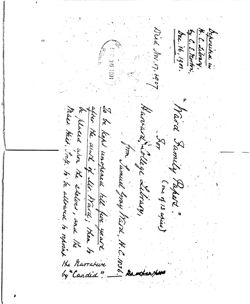

[Series VII] Ward Family Papers (1900) by Samuel Gray Ward

3/18/2016

Athena Holdings Information

Need help locating a book? Guide to Cutter Books I Guide to Library of Congress Books

Log in to your account

ATHENA

THE BOSTON ATHEN/EUM CATALOG

Search

My Searches

My List

My Account

Help

=

=

=

New Search :

Author

Go

Search History

Titles

1 of 1

This item

Ward family papers /

Record View

Staff View

Main Author:

Ward, Samuel Gray.

Ward family papers / collected and written by Samuel

Actions

Title:

Gray Ward.

Make a Request

Print

Contributors, etc.:

Angier, A.A.

Merrymount Press, printer.

Export

Email

Club Bindery, binder.

Publishing Details:

Boston : Merrymount Press, 1900.

Add to My List

Description:

xii, [2], 209, [7] p., [13] leaves of plates : ports. ; 23

Google Books:

cm.

Notes:

"Twelve copies of this book were printed December,

"About This Book"

1900."

"Privately printed."

Binding of full green morocco signed [Grolier] Club

Bindery, 1901.

Ms. note on p. [215] : "The photographs in this volume

are originals made by A. A. Angier."

Local Notes:

Athenaeum has copy no. 7 for George Cabot Ward.

References:

Smith & Bianchi. Merrymount Press (1975), 67.

Subjects:

Ward family.

Provenance/Publisher/etc.:

Bookbinding--United States--New York--New York--1901

Ward, George Cabot, former owner

Call Number:

Rare (Cutter) (Appointment required)

$XD .M55 no. 67

Number of Items:

1

Status:

Not Charged

Reference URL: http://catalog.bostonathenaeum.org/vwebv/holdingsInfo?bibld=27073

https://catalog.bostonathenaeum.org/vwebv/search?searchType=1&searchArg=ward+family+papers&searchCode=TALL&recCount=50&HIST=1

1/2

WARD FAMILY

US42322.9.5,

PAPERS

COLLEGE

is

COLLECTED AND WRITTEN

CARERIDGE, MASS

BY SAMUEL GRAY WARD

through Profeber

December10,1976

Che

Boston

PRIVATELY PRINTED: MDCCCC

[Merrymount Press

tortracts

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INDEX TO PORTRAITS [*]

PREFACE

ix

I. WILLIAM WARD. From a portrait by

WILLIAM WARD: HIS STORY WRITTEN

Stuart

FACING PAGE 16

FOR HIS GRANDCHILDREN ABOUT 1825

I

II. WILLIAM GRAY. From a portrait by

APPENDIX TO THE STORY OF WILLIAM

Stuart

28

WARD

III. THOMAS WREN WARD. From a da-

I. MEMORANDUM IN THE HANDWRITING OF

guerreotype

44

WILLIAM WARD (CANDID), 1761 to 1824

51

IV. LYDIA GRAY WARD. From a daguer-

II. MISTRS. ELIZABETH GARDNER'S LAST Re-

reotype

74

QUEST TO HIM SHE LOVED BEST

54

V. JACOB BARKER. From a portrait by

III. LETTER FROM RUTH PUTNAM WARD (BORN

Inman

1740; DIED 1786) TO MY GRANDFATHER

90

WILLIAM WARD (CANDID)

59

VI. ELIZA HAZARD BARKER. From a por-

IV. MEMORANDUM BY WILLIAM WARD (CAN-

trait by Harding

106

DID)

62

VII. MARTHA ANN WARD. From a draw-

V. LETTER FROM WILLIAM WARD (FATHER OF

ing by Cheney

128

WILLIAM CANDID)

65

VIII. SAMUEL GRAY WARD. From a photo-

SAMUEL GRAY WARD: A LONG LET-

graph

140

TER TO MY GRANDCHILDREN

69

IX. ANNA HAZARD BARKER WARD. From

APPENDIX TO THE LETTER OF SAM-

a portrait by Hunt

I 52

UEL GRAY WARD

213

X. SAMUEL GRAY WARD: . 23. From

a portrait by Page

164

XI. ANNA HAZARD BARKER: . 17.

From a portrait by Inman

176

XII. MARY GRAY WARD DORR. From a

photograph

190

XIII. GEORGE CABOT WARD. From a photo-

graph

204

*

Removed

PREFACE

T'

HE letter of my grandfather, William Ward,

addressed to his grandchildren, and my own let-

ter or memoir, addressed to mine three quarters of a

century later, cover a space of one hundred and thirty-

nine years. Two more such lives would go back of the

first settlement of Massachusetts. We cannot remedy

the want of the earlier record, but I must hope that

some one of the grandchildren I address will, in the

course of the present century, follow our example, and

hand on the family traditions to later generations.

I have given in my narrative such an account as I

could of my grandfather (who in his memoir calls

himself William Candid) as I remember him. He was

the son of William Ward, born 1736, died 1767, and

Ruth Putnam, born 1740, died 1786. This William

is the one of whom my grandfather speaks as being

known by the name of "the Peace and Goodwill of the

family." Only one letter of his has been kept, which will

be found in an appendix. His wife, Ruth Putnam, of

whom frequent mention is made in my grandfather's

ix

memoir, to whom and to whose memory he was all his

after his arrival in this country, died in Virginia on a

life warmly attached, and whose last touching letter to

trading voyage, as verified by the record, including an

him is given in an appendix, was a very remarkable

account of his property amounting to £1108 3s.6d. His

woman for mind and character. The Elizabeth (Weld)

son Foshua (the name erroneously given in my grand-

Gardner, born 1682, whose equally affecting last

father's memorandum as Joseph) was lost in 1677,

letter to her husband is also given, was her grand-

on a fishing vessel; and all of those named above whose

mother.

profession is known, down to and including myself, were

The father and mother of the first William were

in the mercantile profession. Certain family character-

Ebenezer Ward, born 1710, and Rachel Pickman,

istics, as exemplified in my grandfather (William Can-

born 1717.

did) and my father, appear to have been hereditary in

The father of Ebenezer was Miles Ward, born 1672;

the family; viz., an equally strong tendency, alter-

married to Sarah Massey, daughter of John Massey,

nately, towards a contemplative and towards an active

and this John is said to have been the first town-

and even adventurous life; great promptness in action

born male child in the colony. Miles Ward, known as

("a Ward is always in a hurry," is a family proverb)

Deacon Miles, was the son of Foshua Ward, who

when a course is decided on; steadiness in friendship and

married Hannah Flint, December 18, 1668. Foshua

fidelity to trusts; an absence of any marked trading or

was the son of the Miles Ward, the founder of our

accumulating faculty, but a practical ability to bring

family in New England, who came from the town of

about results.

Erith in the county of Kent, England, and had two

On my mother's side, her father, Samuel Gray, and her

grants of land in Salem in 1640. From him I am the

uncle, William Gray, the great merchant, were sons of

eighth in descent.

Abraham Gray, a farmer of Lynn, and Lydia Bur-

The Wards appear to have been ship captains, or mer-

rill. He was the son of William Gray, also a farmer

chants, or both, from the first. Miles Ward, ten years

of Lynn. Samuel Gray's first wife was Annie Orne,

xi

my grandmother. The first Orne, 1602 to 1684, came

to Salem among the early settlers.

WILLIAM WARD

I do not think it necessary to encumber this volume with

genealogical details, which, if the time serves, I will

BORN 1761; DIED 1827

HIS STORY WRITTEN FOR HIS GRAND-

print separately.

SAMUEL GRAY WARD.

CHILDREN ABOUT 1825

January, 1900.

xii

WILLIAM WARD

Y DEAR GRANDCHILDREN,

M

am told you wish me to write a letter

that you may read when you grow up.

I think you may now understand the reasons why

I ought to decline. - My life commenced more

than three score years since, when the advantages

for youth to acquire knowledge were few indeed,

compared with the present. Perhaps it would be

just to say that there never was, by my parents or

relations, ten dollars expended on my education.

At the age of seven or eight years my whole stock

of knowledge was repeating a few hymns, and say-

ing the catechism. From nine to thirteen I partially

attended the town schools; and, for a short time, a

school of a higher class kept by Rev. Dr. Hopkins.

From that time my life has been so various and un-

settled, - SO filled up with labour,- - and no proper

foundation laid in my youth to build upon as I

advanced in life, that my knowledge, even at this

time, is not such as to lead me to believe that,

with your present advantages (which I presume

will be increasing monthly till you grow to years

of discretion and manhood, when your minds will

be so enlarged, and you will be so much wiser than

ever I have been,) what I now write could be

I

pleasing as matter of instruction, to young men so

William Candid was born in 1761, the 28th of

correct, SO wise, so learned as he expects you will

December. He had one brother four years younger,

then be,-although - you might be pleased with it

and one sister two years younger than himself.

as coming from your grandfather. - Yet I am so

William's father died at the age of thirty-one,

much pleased, and have so much pleasure in grati-

when William was six years old. When William

fying them in all their wishes, because they are

was advanced in age, his satisfaction was great in

generally so very reasonable, that I am tempted to

hearing from his father's family, and from gentle-

try to tell you a story of one of my constant play-

men of much respectability, of his acquaintance,

mates in my young days, and of whose life since

that his father was a man of great urbanity, and

I have some correct knowledge.

highly esteemed by all who knew him. He was

His name I will call William Candid. William

called the peace and good-will of the family of his

was the child of highly respectable parents. Colo-

father, which was numerous. William's sister died

nel Pickman, who died in Salem about fifty or

the 25th of May, 1770,-and his brother three

sixty years ago, was own uncle to William's father,

days after, both of the throat distemper. Two days

and Samuel Gardner, with whom your mother's

after William's life was despaired of with the same

uncle Gray served as a clerk, was own uncle to

disease, but he was spared to his mother;-and

William's mother. Those two gentlemen were the

at the age of eight years he was left alone with

first characters in the town and county where they

her. William was then too young to be of use to

lived, for knowledge and usefulness. I mention this

her, but she was a woman of great energy of char-

to encourage you to trace, as correctly as possible,

acter. Your aunt Gray, who died last year, told

your genealogy. You will find as you advance in

William repeatedly of the great benefit she re-

life much entertaining and useful knowledge in

ceived from the advice of his mother. Indeed,

tracing the descent of your father and mother,-

she was a christian. She did for William all that a

of their history &c., in imprinting on your minds

good mother could. William and his mother lived

all the virtues you may hear, from time to time,

together till 1771, when she married again. Her

ascribed to them - and it may lead you to care-

second husband was at that time a respectable,

fulness to imitate all the good and useful traits of

well-meaning man, but of little strength of mind.

their conduct.

He could not grapple with adversity and when

2

3

that assailed him his timidity became evident, and

the prisoners and wounded. Most of the militia

increased. His spirits flagged - his family, his

returned home, and William returned with them.

He was not content; his wish was to be with the

cares, his expenses increased, and he became de-

pressed, and, at times intemperate. When the war

soldiers, and to be engaged in the war. Liberty

in 1775 commenced fear led him to flee, with his

was the cry, and though William knew very little

family, into the country. This act so deranged his

of the merits of the dispute, yet he knew the Brit-

business as finally to lead to poverty. At this time

ish had killed many of his countrymen, some of

William told his mother he was determined to

whom he knew, and he thought they ought to be

support himself,- - to be independent of his father-

destroyed, or driven off. But William remained

at home till the battle of Bunker Hill. He heard

in-law [stepfather]. He was young and small for

his age; had fixed on no plan to gain a livelihood.

the roar of the cannon at that engagement, and

The battle of Lexington took place. William

the next morning he left home, and reached Pros-

walked and ran between twenty and thirty miles

pect Hill the same day. Night was approaching,

that day; passed through Medford late in the after-

he was in the midst of soldiers,--without food,

noon; reached the entrance of Charlestown about

or having where to lodge,-when he met Za-

dusk. He saw a few flashes of guns; but when,

dock Buffington, who commanded a company on

near the heights in Charlestown, he was told the

the hill. Him he knew. Captain Buffington told

enemy had ascended them. The militia were scat-

William it was not proper he should lie with the

tered in different directions, to find quarters for the

troops, and took him to a tent filled with sheets,

night. William attached himself to a Mr. Warner

to serve as bandages and dressings for the wounded.

of Ipswich, whom he knew, and returned with him

In this tent William slept on the sheets; and

to Medford. William wished Mr. Warner to cross

the next and two succeeding days he went to

the fields, where they had seen the flashes of mus-

Lechmere's Point, to the College, to Dorchester

ketry, in hope to find some instrument of war, to

Heights, and saw all the fortifications, cannon,

carry home as a trophy: but Warner laughed,

mortars &c. but being too young for a soldier,

and they kept on to Medford. The houses were

after seeing all that was to be seen, he returned

home.

crowded. They got some supper and slept on the

floor.-The - next morning William saw some of

4

5

It now became a serious affair with William's

ficient, and it was nine months after our arrival

mother and friends what should be done with

before we obtained our object, and were ready for

him. While they were thinking about it, Will-

sea. - On his arrival William walked and ran

iam heard there was a continental vessel bound

home to see his mother. She had not heard of his

to France for a load of small arms and powder for

arrival, and when he entered her room, she looked

the Government. William entered on board of

at him, and said, "Child, what do you want?"

her. When William's friends knew it, they went

She did not know him he had grown so much

to the Captain, and he assented to release him

but when William smiled she knew him and you

but William told them he must go or go into the

may be sure William and his mother were rejoiced

army. His friends finally consented, and William

to meet again.

declared himself independent (a mighty word at

While we lay in France the officers (except Mr.

that day) of them all. He loved his mother, and

Edmunds who was on shore in the city) had com-

agreed to live with her when he was on shore, but

pany on board one evening (for we had several

insisted on paying his board the same as though

officers, and mounted fourteen guns). When the

he lived with a stranger which he always did

company wanted to go away, the boat's crew were

afterwards till he married, and had a family of

called. On going down the side, one of them fell

his own.

into the river, and was drowned. Mr. Edmunds

Early in 1776 he sailed for France. The chief and

heard it was William, and came on board in a great

only efficient officer on board was a Scotchman

rage, scolding at the officers, and every one when

named Edmunds. He was very much attached to

William, hearing a great noise on deck, went up,

William and made him such a passable sailor that

and Mr. Edmunds, seeing him, was astonished,

he was put before the mast in Bordeaux. A load of

and inquired who it was that was drowned. He

small arms and powder was procured for the ves-

was told it was John Quince, a clever young man

sel and she returned safe to Boston. On the pas-

from Marblehead. He told them he rather they

sage was chased into St. Andros in Spain by a frig-

should all have been drowned than William, and

ate. A Dutch nobleman went out in this vessel,

he cried for joy that William was safe.- men-

who had agreed with Congress to load her imme-

tion this to show how much he loved William,

diately; but his exertions and credit were not suf-

and William will ever remember him with kind

6

affection.

7

William on his return from France, had clothed

tor paid constant attention to William till he suc-

himself very decently with the fruits of his own

ceeded in filling the pock. His life was spared,

labour, and had about forty crowns left. He tar-

but there were left five running sores, which were

ried with his mother a few weeks, when meeting

lanced every day for a long while after their ar-

Capt. Jon Haraden, who was then bound on a

rival at Boston. William remained in Rainsford

cruise in a vessel of war belonging to the State of

Island till he finally recovered and went home.

Massachusetts, he invited and urged William so

He found his mother and friends well, and rejoic-

strongly to go with him, and made him such offers,

ing to see him.

which were equal to any that were given at the

time for able seamen, that William assented. This

After a few weeks William sailed again in a Brig

gentleman was one of the first commanders of that

of War, with Capt. Samuel Ingersol. He was a

day : his discipline, knowledge and manners were

pleasant, agreeable man-of correct principles,

exemplary. He knew William in France. Capt.

cool, determined and brave. Capt. Ingersol cruised

Haraden cruised about four months in sight and

some time on the Bahamas, between Cuba and

to windward of the English West India Islands:

Florida-put into the Bay of Honduras, about

came very near being captured twice, but took no

sixty miles westward of Havannah. This is a very

prizes went into Martinico and refitted. William

pleasant bay, but was quite unsettled at that time.

was appointed Coxswain of Capt. Haraden's barge;

- William, with the Doctor and boat's crew were

his station in the main top. After the ship left Mar-

on shore gathering limes &c.-trying to catch

tinico, the smallpox broke out on board. All were

monkeys and wild hogs &c., when William, see-

immediately inoculated: numbers died. William's

ing some hogs approaching where he was, crouched

inoculation did not take. The Doctor scolded and

behind a bush, and as they passed, he sprang to

told him he was always aloft, and never still. He

catch one by his hind legs, when, at the instant,

finally took it the natural way and had it very bad.

the Doctor, not seeing William, threw a hatchet

The pock flattened in, and he came near dying.

at the hog. It missed the hog but hit William,

William had seen all die, in a day's time after their

the smooth flat part of it, on the temple, and

pock had flattened in, but at that time, those who

knocked him over. The Doctor was so confounded

had not died, were generally recovering. The Doc-

at what he had done that he stood to consider

8

9

whether, as no one was then in sight, it was not

have known us. But his Lieutenant was soon on

best to leave William dead, as he supposed he

board us, and explained. He had a vessel follow-

was, or to acknowledge that he had carelessly

ing him in who had sailed from Jamaica, which

killed him, (this the Doctor told William after-

he wished to examine under English colours.- -

wards), but he concluded to see if life was in him.

When Capt. Anthony came to examine his prize,

He did so, and William, by his aid, recovered.

the Captain said, "I am an American my vessel

Had the hatchet struck in any other manner than

and cargo belong to E. H. Derby of Salem; Capt.

it did, it must apparently have killed him. The

Ingersol knows me very well." By our war regu-

Monmouth, the name of the Brig, went into Ha-

lations, we, being in sight, were entitled to one

vannah and hove out, and refitted then sailed

third of the prize, but Capt. Ingersol, knowing

and passed the west end of Cuba, and beat up to

Capt. Silsbee, would have nothing to do with her.

windward towards Jamaica ; took two prizes of

She had two sets of papers. Capt. Anthony took

some value, and sent them to Charleston, S.C.

charge of her, and sent her to Charleston, S.C.

Off Cape Corinth came in contact with a vessel

She was tried by the naval court and given up to

of war of fourteen guns. The Monmouth fought

Mr. Derby.

fourteen guns. Owing to a misunderstanding, and

Captains Ingersol and Anthony having agreed to

supposing her to be an English man of war, we

cruise in company, after a few days fell in with a

gave her a broadside. The Captain immediately,

fine frigate-built ship of twenty guns, from Ja-

with his trumpet, said : "I will send my Lieuten-

maica: he was ordered to surrender; he bid us

ant on board I know you you are the Mon-

defiance; told his force, his number of men &c.

mouth, Ingersol. Follow me inside the Cape, into

The engagement instantly began,-Anthony on

smooth water, where I shall anchor, and then if

his lee bow, and Ingersol on his lee quarter. After

you are not satisfied, I have men and guns enough

a short time orders were given, in a loud com-

to satisfy you." -Still we had our doubts whether

manding tone, that all in the three vessels could

to trust him. He had English colours flying: the

hear, for the two brigs to cease firing with their

two prizes we had taken must have run down

cannon, and every man to arm himself with pistols

the island to double Cape St. Anthony he might

and cutlasses, and Anthony to board on the bow,

have captured one or both of them, and by them

and Ingersol on the quarter, and put them all to

IO

II

death. All were immediately ready to obey and

who had not come into action. He gave as a rea-

were ready to spring on board, when the enemy

son that his officers and crew would not fight, in-

cried for quarter, and hauled down their flag.

sisting that the ship was too much for us, and the

William went on board this ship, but, after sev-

crew had no confidence in their surgeon. Capt.

eral days, Anthony's brig proving very leaky,

Ingersol said all he could to encourage them-

which had increased much after the action, with

promised that his Doctor should attend them &c.,

Capt. Ingersol's consent, he moved everything

but without avail they were afraid. Capt. Inger-

from her to the ship, and left the brig to sink in

sol advised Capt. Gray to proceed home imme-

the ocean - meaning to cruise in the ship and meet

diately, and he left the Monmouth. Capt. Inger-

the Monmouth in Charleston, S. C.

sol proposed going alongside the ship again, but

the crew thought the ship would be so much

Being left to themselves, William still on board

encouraged to see one run off, that they should

the prize ship, they continued cruising in the en-

not succeed. This ship put into New York very

trance of the Bay of Honduras. In a few days they

much damaged, with much loss of men, and very

took a twenty gun ship bound into the bay to load

valuable. In this engagement C. O., stationed in

for England. She surrendered after two broadsides.

the Monmouth's fore top, deserted his post in the

They then cruised on the north side of Cuba, and

midst of the action. William liked C. and pitied

fell in with a vessel of war of fourteen guns com-

him, and told the sailing master he would take C's

manded by Capt. R. Gray of Salem. The comman-

place and C. should take his but he was not al-

ders of the two vessels agreed to keep company,

lowed. Poor C. with many others were wounded,

and falling in with a ship of twenty guns, frigate-

but only one died. The Monmouth put into Charles-

built, from Jamaica bound for London, they en-

ton, made a short cruise from thence, and returned,

gaged her one hour and a half, within pistol shot.

and then proceeded to Salem. William found his

The enemy's ship was very high and the Mon-

mother well, and with his prize money, was able

mouth very low, SO the shot from the ship passed

to confer benefits on her and his friends.

over the deck of the Monmouth, while the Mon-

mouth shot did great damage. The Monmouth

William's next cruise was in the Harlequin, a ship

hauled off to refit, and to speak with Capt. Gray,

of twenty guns, James Dennis commander. Cruis-

12

13

ing between Cape Race and Cape North, they

tain and officers were the most deserving. Of those

took a valuable ship, after a long action, though

eight shares three were given to William on the

with little loss - one killed and several wounded.

arrival of the Harlequin and her prizes at Salem.

In this action William was called from his station

William's next cruise was in the brig Lion, J.

(viz., Captain of the fore top with four men, two

Carnes commander. It was an unfortunate cruise

swivels and a chest of small arms,) to the quarter

of six months and only one prize. Carnes was brave

deck, by Capt. Dennis, who wished him to take

but vain and foolish. The boatswain of the Lion

his spy glass and give his opinion of a strange ship

was a remarkable fellow of that day ; daringly

just hove in sight, and to tell him that the wads

brave, if judged by his boasting words, and his re-

for the guns were expended. Such was the disci-

markable profaneness. His name was Harry Poor.

pline at that time on board of one of our twenty

The Captain had given Poor's mess some fresh

gun ships, that a lad was called to the quarter deck

pork, which Harry made into a sea pie and swore

to give advice. William gave his opinion of the

that God Almighty should not prevent his mak-

ship in sight, that she was an American cruiser,

ing a good dinner of it in a few minutes after his

who would soon be up, and take the ship they

head, face and stomach were covered with red

were engaging and put them to shame, and ad-

blotches, with swelling and fever; he was greatly

vised to press nearer to the ship and oblige her to

frightened and could not eat. His messmates ate

surrender before the strange ship could get up.

the sea pie, and Harry recovered the next day. He

William replaced the wads with junk and blan-

was a gambler, and one night at Marblehead, hav-

kets, and returned to his station, while the officers

ing ill success, he wished the Devil might come

generally were doing nothing but looking on. The

and fly away with him. It was a dark night; Harry,

ship soon struck her flag. A few days after they

going home, fell, found himself taken up and run

took another valuable ship after a short action, and

off with. He screamed and hollo'd, thinking the

a brig. Both were bound to Quebec, the one laden

Devil had got him sure enough. The fact was,

a

with all kinds of provisions, the other with dry

cow was laying in the road; he fell between her

goods. In our vessels of war at that time there

horns; the cow was frightened and rose with him

were eight shares set aside to be distributed among

and ran. He finally died in a consumption, a mis-

those of the crew who in the judgment of the Cap-

erable man.

14

15

The Lion in returning home, in doubling Cape

the Experiment, and the following account was

Cod, fell in with the Experiment, a fifty gun ship,

from him.

and the Unicorn of 20 guns. Those two drove her

The ship they gave chase to was an American frig-

ashore on the banks of the Cape the enemy came

ate, the Raleigh, Capt. Berry. They chased her

to an anchor, got spring on their cables and began

from the Cape to the eastern shores. The Unicorn

to fire away; the Lion was on shore head on and

outsailed the Experiment, and Captain Berry think-

could do nothing; her barge was ordered out; as

ing he might capture the Unicorn before the Ex-

soon as she took the water, so many in the fright

periment came up, headed to; the action began,

jumped in, that she sunk alongside. The situation

when an unlucky shot from the Unicorn knocked

of those remaining on board was serious; for the

away the Raleigh's foretop mast. She was obliged

enemy were manning their boats to come in and

to put before the wind again and finally run ashore

set fire to the Lion. It was necessary something

on an Island laying a small distance from the main.

should be done. William with six others jumped

The Unicorn anchored, got spring upon their ca-

into the sea, at a great risk; the sea was high and

bles and began to fire. The Raleigh beat her off;

rolled in with such force as to turn them head over

the Experiment came up (it was night), hailed the

heels, and fill eyes, nose and mouth full of sand;

Unicorn, inquired, was told that it must be a French

they reached the shore, got those on shore who

74, for he could not do anything with her; and was

were swamped in the barge, all but one, alive;

obliged to haul off; they then both placed them-

launched the boat, went alongside, took in some

selves as near as possible to the Unicorn and com-

plank and guns, landed them, got hauling lines

menced a heavy firing, but finding no return they

from the shore to the vessel, landed the remain-

boarded her and found only one drunken sailor,

der of the crew, and were soon in a situation to re-

the rest having landed on the main, and he swear-

ceive the enemy's boats which were then rowing

ing he would never strike.

in; but at that moment the enemy from their ship

William and his six friends went from Cape Cod

saw a large ship in the offing, recalled their boats,

to Boston in a small boat and shortly after with

got under way and gave chase to the ship they

thirty-nine others, bought a vessel, fitted her out

had just discovered. The Lion's prize on board of

as a cruiser with ten guns. These forty owned the

which William had a cousin had been retaken by

whole in equal shares, all performed equal duty

16

17

and they all sailed in her; they named her the

the air very impure; some stifled and died in the

Modesty and cruised off New York. One morn-

night. The next day the Modesty's crew turned

ing, it being William's turn at mast head, he told

them all on deck, then made them wash, scrub

them on deck that at leeward he saw a brig with

and clean, bathed them at sunset, made more room;

fore top mast gone and a fleet of twenty sail in

the air became more pure and none stifled after-

shore, all standing in for the Hook. The Brig

ward they regulated the ship while they stayed

might have been captured in a short time; she

and had her cleaned every day. The Captain who

was taken next day by an American and proved

took them redeemed his pledge and they were

very valuable, but the Modesty's crew thought

exchanged in about three weeks, landed in Boston

nothing less than five or six of the enemy's fleet

and walked to Salem.

would satisfy them. One ship in the fleet appeared

to sail heavy and we gained on her fast, when she

William's next voyage was to Hispaniola, to the

tacked and stood for us. We were not deceived

Cape and back, in a very fast sailing letter-of-

long, she proved to be a 20 gun ship, and out-

marque owned by Joseph White, commanded by

sailed and captured the Modesty. Her crew being

U. Stone. A French flour barrel of good sugar

all strung along on her quarter deck, the stranger

might then be bought there at four dollars, the

Captain began asking questions, and when he was

produce of the island being very cheap.

informed of the name of the vessel he had taken

William then engaged in the Harlequin, Putnam

he laughed very heartily for the modesty they had

Cleves commander; The ship he had been in once

exhibited in chasing one of her Majesty's ships,

before with Captain Dennis, cruising ground the

but said their plan was a good one, and they were

same, viz. Cape Race and Cape North. Cleves was

such likely fellows he was sorry they had fallen

clever and sprightly, but not much judgment, his

in his way ; that he would interest himself in get-

officers very much like him, not much firmness

ting them exchanged soon, that they might try

when it was most needed, and not much forecast.

it again. They arrived in New York, were put on

Took one brig came near being captured twice

board the Hope, a prison ship; she was uncom-

by a ship evidently cruising for her. One foggy

monly large, had eleven hundred prisoners con-

afternoon saw a fleet under convov; it was Will-

fined between her decks; she was extremely dirty,

iam's watch that evening from 8 to I2. Captain

18

19

Cleves ordered the course. William stated that

winter there. There was but one outer door to the

with the course ordered we should be in the midst

building, and when you entered that you entered

of the fleet. He was not believed, and one after

the guardroom. There were three rooms beside

another left the deck, all but ten or twelve when

with two windows in each looking into the yard,

an hour after the fog scattering a little, the Har-

inclosed with iron bars. In the first, next the

lequin was actually in the midst of the fleet sails

guardroom, were the Harlequin's people. In the

reefed, top gallant mast housed, men asleep &c.

second and third were American soldiers. William

William ordered silence, without noise gave no-

soon began to think of escaping. It required prepa-

tice below, ordered the reefs out &c., but a frig-

ration, and he and his shipmates saved every day, a

ate was so near as immediately to discover them

part of their allowance of beef; cured it and smoked

and began to fire with them. By the great exer-

it. They obtained a pocket compass, and then be-

tions of a few she escaped. They still kept the same

gan to break through the prison floor, in order to

cruising ground, when one morning the same ship

get below into the cellar. To do this much labour

was discovered directly to windward of the Har-

was necessary. The stones were placed under their

lequin. She soon came in full chase, and soon

berths and they piled wood against them that

proved that, going large, she was the fastest sailer.

they might not be perceived but by some means

When she got within musket shot, the officers and

the commissary was informed he came with the

people dodging, Capt. Cleves ordered William to

guard and examination was made. When he came

haul down the colours. He with feelings of con-

to the room where William was, having passed

tempt and mortification, walked aft, and took the

through and searched the others first, William

flag in on deck. They were carried to Quebec, to

was alone in the room, the other prisoners having

prison. There were two stone prisons enclosed in

followed him in his search. He told William to

a large yard, with a stone wall, one of two stories,

haul away the wood from under the berths. He

the other of one. About forty of the Harlequin's

did so and down came the stones. Then he began

crew were put into the two story one, and the re-

to threaten and scold, and said he should prefer

mainder into the other. Among the last was Will-

having a whole regiment of soldiers to take care

iam. There was no exchange of prisoners at that

of than twenty sailors. "You are treated well, have

time, and the probability was they would have to

good provisions &c., and yet you behave in this

20

21

vile manner. What is it you want ?" William told

enough for a man to crawl through would let

him they wanted air and exercise. "Let us out into

them all out at liberty. They kept their secret,

the yard every day, as you do the soldiers, that we

renewed their preparations for a long journey

may play ball &c., and throw off this prison gloom."

through the wilderness, and expected soon to be-

The commissary said, " If I indulge you, will you

gin their enterprise. At this time the commissary

behave well? Answer, Yes." - Well ! you shall

took William to his house, guarded by a soldier

have the liberty of the yard."

showed him his garden, and was kind in his con-

The prisoners were let out the masons were let

versation &c. William thought his conduct was

in the damage was repaired, and the prison made

strange and inexplicable but concluded that the

stronger than before. Soon after William was in

old gentleman thought that if he could get rid of

the yard, he looked into one of the cellar lights

William, he should get rid of trouble; the rest

and immediately saw what had occasioned the

of the prisoners would be quiet and that he took

difficulty. The room was arched, and they had

this plan in the hope that William would attempt

ignorantly begun their hole on the side of the

to run away, and then he could be intercepted

arch, instead of the end. When they were locked

and put by himself on board a man of war. A lit-

in for the night, William began in the center, and

tle while after this the commissary came into

took up a large stone, with a few small ones, and

the prison, and said there had a cartel arrived in

made a hole large enough for a man to go down

the river from Boston and all were to go on board

he then placed some small pieces of wood across

her next day and be sent home. William's ship-

and replaced the stones; swept the dirt over and

mates believed it and sat up all night rejoicing.

no one could perceive what had been done. The

William at that time was engaged to a lady whose

next morning William was let down with a rope,

brother, Thorndike Proctor, was one of his prison

and he quickly examined the place, its width and

mates. William told Mr. Proctor privately that

length he discovered a large drain &c., and was

he did not believe a word of the commissary's

hauled up again. When they were let out into

story he believed they were all to be sent to

the yard he found the drain led to the seaside-a

England and there confined in prison, and that,

long distance that from the back of the cellar to

if it were possible, he should escape, and begged

outside the wall was 28 feet; so that a hole large

him to be near him that he might take his bag

22

23

of clothes &c. but Proctor did not think with

sue the subject they left the brig and the pris-

William. The next morning such a guard of

oners were distributed on board the fleet. William

soldiers surrounded them, and so many people

was put with eight others on board a Transport

assembled to see them let off, that it was impos-

of 300 tons, and about thirty men, armed with

sible to escape, and the instant they reached the

six or eight cannon, and immediately all were

river they were put into boats and from thence

put in irons their feet above the ankles, on one

on board an armed brig. The Captains of the two

large bolt, a large head at one end the other end

frigates came on board, and from the quarter deck

through an oak plank bulkhead. In this manner

told them that those who were willing to enlist

they were kept under deck. The fleet sailed under

on board his Majesty's ship should have good

convoy of two frigates. In three or four days a

treatment &c., and those who would not were

violent storm sprang up, and lasted about twenty

to be distributed on board the fleet of transports,

hours. The transport William was in, suffered

and sent to England, and there be confined in

much, and she was separated from the fleet. The

prison till the war ended. William's shipmates

Captain came down and asked the prisoners if

had been up all night talking of their homes,

they were willing to help repair the injury done

their wives and sweethearts, expecting to join

by the storm. They assented they were let out of

them in a few days. The disappointment was so

irons, went on deck, worked all day very briskly,

great and unexpected that the stoutest and brav-

and got the ship in good order. The Captain

est men among them fairly cried like children.

scolded his crew, and told them the Yankees

William was vexed; no answer was given to the

they had laughed at had done more that day,

British Captain. The proposals were again made.

than they would have done in a week. He apol-

William then stepped towards the quarter deck

logized to William for the necessity he was under

and said "I am a prisoner, and wherever you

of putting them in irons again, saying he knew

choose to place me I must remain a prisoner till

what it was to be a prisoner, and in their case, he

I am exchanged, but I will never contend against

should try to get his liberty again, therefore he

my brethren in arms and join my country's ene-

must confine them. William told him he sup-

mies. I believe, gentlemen, I speak the sentiments

posed it was his duty to make them as secure as

of my fellow prisoners." The Captain did not pur-

possible, and that if opportunity offered he should

24

25

endeavor to regain his liberty. They were put in

his shipmates and had told the Captain. William,

irons, the next morning were again let out to aid

finding all was discovered, reminded the Captain

in refitting the ship. The Captain appeared fond

of their former conversation, that he had not de-

of William.

ceived him, and frankly told him to do his duty,

About IO A. M. William observed that his ship-

and that he, if a chance offered should and would

mates were the only people on deck excepting the

improve it, to regain his liberty. A great deal was

man at the helm and the cook he found the Cap-

said, but it ended in putting them all into heavy

tain, officers and crew were in the holds betwixt

irons, and being treated with great neglect. The

decks putting things in order: that there was only

next day the ship joined the fleet. Several days

one hatchway for them to come on deck, and that

passed before the ship got outside the capes. In

if that was secured, the ship was in possession of

this interval he found from two of the ship's crew

the prisoners. William immediately represented

that if an opportunity offered the sailors would not

this to his shipmates, told them only to assist him

resist; they would like to go to Salem or Boston.

in putting on the hatch and they might be home

He found the Captain lay in the state-room, a key

in ten days, instead of going to England he made

always in the door on the outside; he had a pair

use of every argument he could think of, but they

of pistols and an old hanger, and that there were

were afraid; the proposition was sudden, they had

no other arms below which he or any other per-

not nerve. In a very little while the Captain, of-

son could suddenly get at that the second mate,

ficers and part of the crew came on deck. William

sailmaker and carpenter lay under the steerage

with a biscuit for a plate, and a piece of salt beef

deck, and a small scuttle at the foot of the cabin

on it, which he cut with his knife, began his break-

stairs would secure them. Having provided a good

fast and jcined the Captain, who was walking on

file and having satisfied himself that in half an

the quarter deck, and he began to converse. The

hour he could let himself and his friends out of

Captain then burst forth, called William many

irons, he then talked with his fellow prisoners and

bad names. William inquired what he meant.

explained everything to them They all solemnly

Mean, sir," said he, "You were going to take

agreed to be true to William and to each other,

my ship from me this very morning !" The cook

and each one to perform his part in good faith.

had overheard part of what William had said to

An easterly gale was blowing,-the fleet under

26

27

very short sail about ten at night, the mate's

held on with both hands, his body hanging down

watch on deck, the boatswain on the main deck.

the steerage hatchway; he must have soon dropped,

William engaged to be first on main deck, to seize

for he could not long sustain the blows he was re-

the mate and confine him till they got the ship

ceiving.

out of the fleet. Davis of Marblehead had a seizing

of spun yarn for that purpose and was to follow

At this critical moment the Captain came up and

William and keep by him. William Chapel of

fired one of his pistols at William. The truth was

Marblehead was to follow next and go into the

that all the rest, as fast as they came on deck, were

cabin, lock the state-room door, to secure the

frightened at their undertaking, and instead of do-

Captain. Jo. Shillaber and one other was to follow

ing what they had engaged to do, went immedi-

Chapel and put on the scuttle and fasten it to keep

ately forward, and left William to fight it out as

the second mate, sailmaker and carpenter fast;

he could. William being abaft the hatch, and his

then those three were to come on deck and obey

face being aft, he did not perceive their conduct,

William's directions the remainder to go on the

and expected every minute to be assisted by some

main deck, order the crew below, and put on the

of them: but the mate, whose face was towards

hatches. William was confident, if he could once

them, and saw them all go forward, found it would

obtain possession, he could soon trim what little

not do to give up to William alone. The Captain,

sail was out, so as to leave the fleet; or he could pos-

hearing the noise over his head, was alarmed and

sess himself of the Captain's instructions and signals

came up. He fired and showed his signal lights;

and by that means, even keep company with them

the frigate was soon within hail, when the inquiry

for several days without being discovered. All were

was made, "What is the matter? The Captain

armed with good clubs William led the way and

answered that the prisoners had risen upon the

seized the mate, and told him if he would go be-

ship. "How many prisoners have you? Answer,

low, without noise or resistance, he should fare

"Nine." - " How many in your ship's company?"

well, otherwise he must abide the consequences.

Answer," Thirty." will have your commander

But he parlied and resisted a contest between

flogged. Can you secure them till the morning

them began, and William beat him from aft to

Answer, "Yes." - Very well ! I will send my

the main mast, where he seized the rigging and

boat alongside at sunrise." - The log line was cut

28

29

and William's hands and feet were tied. The Cap-

lose his life if he did not do all he could to re-

tain then came to William and began cutting at

sist; that if William had made a confidant of him

him with his hanger, and wounded him in several

all might have been well, for he wished to go

places. William expostulated and told the Captain

to America; he regretted that William would

how very improper his conduct was; that he was a

be obliged to leave the ship in the morning, and

prisoner; he could not make any resistance; neither

be sent on board the frigate, where he would be

could he fear that he could do any further harm.

treated very ill, &c. William told him it was best

All this time the Captain was beating him. The

he should leave the ship; he could not live in

mate, finally, made him desist, and persuaded him

peace and good will with those who had so basely

to go below. The night was wet and cold. Will-

deserted him; and as to being treated very ill, he

iam entreated the mate to loosen the line that con-

did not fear it, he was a prisoner and expected to

fined his wrists, and told the mate it would be no

be treated like one.

satisfaction to him for William to lose forever the

use of his arms; that the circulation was stopped;

In the morning William was taken on board the

that he had nosensation in them; and could not tell

frigate. When he reached the quarter deck the

whether he had any arms or not. The mate said

Captain asked him what countryman he was. He

he was astonished that William should ask any fa-

answered,

an American. You are a rascal then, of

vour of him, after beating him over the head as he

course" and he struck William with a bell trum-

had done. William told him how he had planned

pet in his face. The sailing master of the frigate,

everything, and if his mates had done what they

who had talked with the boat's crew who had

had promised to do, there would have been no OC-

been to fetch William on board, told the Captain

casion for any beating. The mate then loosed the

that William ought to be praised for his conduct

line, and sent for William's great coat to lay over

on board the transport, and the rascals that were

him, and told him he could not help observing

left behind were those who deserved punishment.

how his friends deserted him; for he hoped every

It will answer no good to tell minutely how badly

minute, some of them would come that he might

William was treated by this brutish Captain.

surrender and have some apology; for the man at

When William told him he had never been ac-

the helm must see all that passed, and he should

customed to such treatment, he cursed him, and

30

31

said he wished he had his General Washington on

said, "Here must be some mistake ; you are not

board, he would treat him in the same manner.

to go; the Captain has a particular liking for you,

Handcuffs were made out of iron hoops on pur-

and has sworn that you shall never leave the ship."

pose for him. The hoop went through edgeways

William begged him to let him pass in the crowd,

on his wrists. He was kept on very short prison-

and no one would notice it, and he would do an

er's allowance,-and one day when they were ex-

act of kindness and humanity. He turned away

pecting to come into action, William was called

and William passed on and was landed a prisoner

to the quarter deck, and the Captain told at what

in Portsmouth the next day.

gun was his station, and if he did not go there as

soon as the action commenced, he should be spread

William was taken before the Admiralty court to

out and tied to the mizzen shrouds for the enemy

be examined. The judge appeared kind to Will-

to fire at. William told him he would as soon be

iam and told him he might be a free man in a

there as anywhere else, but he never would fight

few minutes, if he would declare that he was not

on board his ship.

taken in an armed ship fighting against his Maj-

The frigate put into Ireland, and the women who

esty but if, when the question was put to him,

came on board to sell articles to the crew, cried

he should say that he was captured in a ship of

over William's hands and wrists, which were raw

war, then he must sign his own condemnation, he

and swollen. Every night while he was on board

would never have another trial, and when his

he was put into the lower hold, in the kentling of

country was subdued, he must suffer with the

the water casks. After leaving Ireland and going

rest. The judge inquired of William if he under-

up the English Channel, the frigate passed a fleet.

stood him. William answered yes. He then put

The Admiral sent word that the frigate should

the question. William thanked him for his kind-

proceed immediately to Guernsey, and if he had

ness, but told him he was taken in a 20 gun ship,

any prisoners on board he must put them on

with a commission from Congress, fighting against

board the Britany store ship, which would be

the enemies of his country. "Well sir, you must

near to take them. William on passing over the

sign your own condemnation." William signed

side with the other prisoners, to go on board that

his name. He had no doubt that the judge was

ship, was stopped by a young midshipman, who

telling him the truth, but with an evident inten-

32

33

tion to deceive him. Had he answered as the

parts of the United States, generally young and

judge advised, he would have been told "You

middle aged, some old. Their characters and habits

are free, and you may leave the office" but as

were various, in general pretty correct, some very

soon as he got out of the office, he would have

bad. But little attention was paid to cleansing

been treated as a British subject, immediately

vermin everywhere, in their beds, their bodies,

pressed, and sent on board one of his Majesty's

their heads, in the walls and in the yard, crawl-

ships. The judge said he was surprised that Will-

ing on the palings. There was no general obser-

iam could write so well it was not common

vation of the Sabbath, which was mostly employed

he said among their sea-faring people. William

in making boats, ships, snuff boxes, and various

told him that every town and village were obliged

toys; shoemaking and anything to obtain money

by laws, (of their own framing,) to keep free

to buy bread, milk, coffee &c.

schools. William was then sent, under a guard, to

Gosport prison. Dutch, French and American

William had been treated so ill and suffered so

prisoners were within its enclosures, each sepa-

much, that when he got to the prison, and his

rated by high walls and palings, with a strong

excitement began to decrease, he was taken down

guard, relieved every morning. The government

with a fever; put into the hospital recovered

allowed each prisoner a pound of beef and a pound

slowly ; then relapsed was out of his senses and

of bread per day. The allowance for banyan days

given over.

was peas and oatmeal. The government allowance

At this time Captain Ives of Beverly made his

passed first from the commissary, who made the

escape, and reaching home by way of France, he

best bargain he could for himself, with a con-

reported William's situation to his friends. Will-

tractor,- contractor with the butcher then

iam finally recovered and made up his mind to

the cook, and a host of stewards, nurses &c., so

turn his sufferings to some good account. To do

that when the prisoner received his daily allow-

this it was necessary that his person, his clothes,

ance he could eat it all at one meal, and then he

his bedding, should all be clean, and to fix on

was hungry till the next day. There were about

some place where he could keep so. The prison

two hundred and fifty American prisoners at this

was three stories in height, with a gable roof, the

place, many of them of good families in various

end facing Portsmouth, Spithead and the Isle of

34

35

Wight. Air pumps reached from the lower story

week to each prisoner. William made out with

to the roof. The upper chambers were not lathed

his allowance to eat his meat and a part of his

nor plastered. William climbed up by the air

bread at dinner, and for his breakfast the remain-

pump, walked on the joists to the end, and tak-

der of his bread boiled in water and seasoned with

ing out two or three tiles from the roof, he re-

salt. Supper he had none, but he knew that if he

placed them with oiled paper he braced a wide

lived he should want knowledge, and, hungry as

canvas bed from the side joists, made him a little

he generally was, he kept to his study.

writing table just under his window, which was

partly secured to the end of the building, with

You have, or will read, of the famous philanthro-

two lines to hang and steady the other part. He

pist Mr. Howard. Dr. Wren was another How-

then made a hanging seat facing the table and the

ard. He was a Scotchman, a dissenting minister in

window. In fair weather he could remove the win-

Portsmouth, highly respectable and very much es-

dow, and have a good prospect before him. He

teemed. He traveled for the prisoners; he begged

then cleaned all his things, ironed them. with flat

for them ; and but for his exertions their sufferings

irons which he borrowed, placed them away, and

would have been extreme. Always once, and gen-

dropped a screen behind him.

erally twice a week, he came into the American

prison yard, followed by two porters laden with

He now had a clean berth to himself, which he

supplies for the prisoners. Fancy to yourselves an

climbed to by the air pump and very seldom did

elderly gentleman, with a fair complexion, and a

any one take the trouble to climb up to molest

fine loveable countenance; dressed in a shirt of

him. Here he studied hard to prepare himself

dark blue, with a white wig, standing in the mid-

for usefulness amid brighter prospects, when he

dle of the yard dealing out all kinds of clothing,

should once more reach his own happy land. He

pens, ink, paper, books &c., and when the porters'

exercised in the morning and before sunset with

bags were empty, hear the cry all round him Dr.

ball, broadsword, &c. He was in this prison nearly

Wren I want this, and I want that," from numerous

a year. A part of the time the American govern-

voices. All their voices he knew,-he wrote in

ment made out to obtain credit, to allow through

characters, seldom looking up while writing. His

their agent, the Rev. Dr. Wren, one shilling a

dispatch was surprising, and his accuracy astonish-

36

37

ing, for amidst all this cry and tumult of voices,

but he must have opened it first, as he appeared

which a bystander would have thought impossi-

afterwards to be very partial to him and this pre-

ble for him to have understood, or noticed at the

caution was necessary for his own safety.

time, - -yet, when he again came, each man re-

A friend of William's father called to see him, a

ceived, as his name was called over by him, what

Mr. Sparhawk. He talked much of William's fa-

he had asked for. When he first began his atten-

ther and made many professions. Pickman

tion to the prisoners, it was at the risk of his life

was, at that time, in England, but William did not

from the rabble; a guard of soldiers always at-

know where to direct to him. William requested

tended him whenever he was in the yard, to watch

Dr. Wren to find out by Mr. Sparhawk. Dr. Wren

all he did. Many of the prisoners wished to send

soon after wrote to William that he had met Mr.

letters home to their friends; many of their friends

Sparhawk in London; he found him a dispirited,

found means to send letters to the care of Dr.

gloomy man, much averse to his countrymen, and

Wren. He found it necessary to have a confidant,

the cause they were engaged in, herding, chiefly,

as his fame and living, and even his life, depended

with refugees; but he told him where Col. Pick-

upon his holding no correspondence with the pris-

man was. William corresponded with Col. Pick-

oners,-beyond what has been related. He chose

man, who sent him two guineas.

William, secretly, for his confidant, and William

always, when he was in the yard, placed himself

Dr. Wren had received special directions to care

directly behind him, apparently looking over his

for and attend to John Higginson of Boston. He

shoulder, and would take from hisright coat pocket

was wild and the Doctor could do nothing with

whatever papers were there, and put in others.

him. William took him in hand, and he improved

This was done weekly. Much caution was neces-

much and behaved well, to the surprise of Dr.

sary, but the crowd around him was great, and

Wren and every one.- One evening word was

the soldiers had no mistrust. He became acquainted

passed for William-an officer wanted him. He

with William by means of a letter William had

went down and saw a fine looking young man in

written, soon after his arrival at the prison, to his

British regimentals. He inquired of William if he

mother and friends, and which he requested Dr.

knew him. William told him no. 'What! do you

Wren, in writing, to forward. He did forward it,

not know your old playmate William Browne?"

38

39

Browne got liberty of the officer on guard for

manly man, when he was told the reason for the

William to spend the evening with him, in the of-

ficers' room. Gen. Gage had given William Browne

illumination, viz., to rejoice for the victory their

a commission, and he was on his way to join his

countrymen had gained, merely advised good or-

der &c. and took no further notice.

regiment in Gibralter. Before the war Browne's fa-

ther lived directly opposite the house where Will-

Shortly after the Duke of Richmond, Lord Lennox,

iam's mother lived, and was highly esteemed by

Gen. Conway &c. came into the prison and con-

all classes; but he joined the British, and fied his

versed with the prisoners and examined their pro-

visions. After this the allowance was increased.

country. Browne was very agreeable, and William

An American sailor defrauded an old woman who

spent a pleasant evening with him and the officer

on guard. An officer came into the yard one day

sold sundry small articles to the prisoners : Will-

to see the prisoners; he had a large fine dog with

iam had him flogged at the lantern post. After-

him; the prisoners contrived, while the officer

wards an officer, a Virginian of respectable family,

was looking about, to steal the dog, and secrete

stole from a young lad William had him flogged

him. The guard was turned out and great search

the same as the sailor had been.- - An exchange of

was made, but he was not found. Half of the dog

prisoners was at this time agreed upon, and Dr.

Wren, supposing William might soon return to

was roasted the next day, and half boiled and soup

made of it. William tasted part of each, as a mat-

America, wrote to him, and requested him, if he

ever had a son, to name him for him.

ter of curiosity,-for he had received the two

guineas from Col. Pickman about that time, and

he did not eat it from hunger.

Finally, the cartel being ready, two hundred and

thirty prisoners embarked in one ship for home.

A bladder was picked up in the yard one day, and

Once more William felt himself at liberty. He

in it a newspaper, containing an account of the cap-

now experienced the benefit of his studies while

ture of Lord Cornwallis. The prisoners, as soon as

in prison he could impart information and use-

they were locked in for the night, illuminated the

ful knowledge to those who had wasted their time.

prison the officer on guard was alarmed and the

- The passage home was long-sixty days. They

guard was turned out. The officer, being a gentle-

arrived in Marblehead on Sunday forenoon. Will-

iam was the first on shore; he ran through the

40

41

town, the people-women and girls - -following,

He was examined before the governor with many

and asking if A or B or C or D had come. Will-

other prisoners. After the examination the Gov-

iam kept on running, answering yes, - and crossed

ernor ordered the prisoners to be put on board the

the fields and was soon seated on the hill to rest

prison ships; but, advancing to William, he said,

himself, where the powder magazine now stands

taking him by the hand, "This young man must

near the turnpike. Here he could look down on

tarry with me." He then said, "My wife must

the house where his mother was, if living. It was

know you are here; she is unwell, but I will speak

about one 'clock-between meetings- - no one

to her." She came and said "Oh, you rogue, I am

stirring. He mustered courage - descended the

glad you have been taken you used to steal my

hill - went into the house, and found his mother

cherries with my son William." The British gov-

living and in good health. It was a time of over-

ernment had made Col. Browne, father of the

flowing gratitude and love. William's friends were

William Browne who visited William in prison,

all overjoyed to see him.

at Gosport, Governor of Bermuda. The Governor

and his lady treated William with great kindness

William had left some property at home, but it

and attention. The gentlemen of the place were

was all gone. His old friend Mr. Edmunds, who

very attentive; the commissary of prisoners gave

was so much attached to him on his first voyage,

him two dollars per day for his services and he

had while William was absent, taken charge of

was offered the command of a vessel by a mer-

a fine ship for Spain. The prospect of profit was

chant, for a voyage to St. Thomas, but it was

great and Edmunds told William's uncle and

against the orders of the general government.

mother he would take an adventure for William

There was a flag to be fitted out for Virginia. The

free of expense. Edmunds was taken on his home-

Governor and commissary advised William to go

ward passage, carried to Halifax, and he there died

first officer in her, and promised him, when he re-

in prison, and with him what property William

turned, the Rhode Island flag ship as long as the

had was lost.

war lasted. This flag service was profitable and

safe. William went to Virginia and returned to

He next went mate of a brig to Granada. Coming

Bermuda. He then took charge of the Rhode

home, he was captured and carried to Bermuda.

Island flag ship, and was busy in fitting her out,

42

43

when the news of peace came. William's friends

him never to neglect him, nor any of the children,

in Bermuda urged him to tarry with them, and

to watch over them, to advise them, and to do them

offered him every encouragement, but when they

all the good he could, while he and they lived.

found they could not prevail on him, and the flag

William promised her, and, in some good degree,

was ready, they fitted him out with every neces-

faithfully redeemed the pledge he gave her. The

sary, the Governor putting on board a hogshead of

family cost him thousands of dollars, with great

pure cistern water for him. They were landed in

affliction and trouble, but the wishes of his mother

Providence, and went home from there by land.

sweetened all ; he was doing what she desired, and

she lived long enough to take William's son to

The war was ended, and William was twenty-two

her dying bed pray over and for him, and

years old, and pennyless, and had to begin the

to leave him her blessing.

world anew. - He was soon established as a re-

William's wife died in 1788. In person and mind

spectable shipmaster, and one of his first voyages,

she was of superior excellence.

to Europe, was to England. When he arrived

there he found his friend Dr. Wren was dead.

While in Bermuda William again met John Hig-

ginson-he was a prisoner, poor and destitute.

William married at twenty-three, and was blessed

William clothed him and gave him half his little

with a son, who was named after his revered and

fund, and introduced him to the Governor and his

beloved friend, Thomas Wren. William's mother

family. William had it in his power to be, and

died in 1786 at the age of forty-six years and eight

was of much service to many American prisoners

months. Her unwearied patience with William,

there. Many of them wished William to take ad-

her constant perseverance in the performance of

vantage of the trust reposed in him and aid them

all the duties of a kind, affectionate, and christian

in escaping, with a vessel. William told them that

mother, towards him, were uniform. The day be-

the Governor had confidence in him, and he would

fore she died, she told William, that his father-

not forfeit it. William's friend, William Browne,

in-law [stepfather] was fearful that William would,

though holding a British commission, was SO much

at her death, forsake him; that he confessed he had

of an American as to be often fighting their cause,

not treated him kindly, &c. His mother begged

in duels with his brother officers. His mortifica-

44

45

tion was great that his father had forfeited so great

class, yet his own family needed all they could

an estate by joining the enemies of his country.

obtain, and the opportunities of increasing their

He died in early life.

means were extremely limited, as compared to

what they have been since.

In giving you this hasty sketch of William's life,

William had understanding sufficient to perceive

you will notice that his errors are not noticed. If

all the disadvantages under which he laboured,

you hear of them from others, let them be beacons

and while his most intimate associates were fitting

to you, and avoid them in yourselves. Your father

by education to take a stand of honour and use-

can give you William's history up to this day, and

fulness, he with firmness and hope, which never en-

you will notice how varied his life has been.

tirely forsook him, though oft-times discouraged,

You now begin to observe the diversity of char-

determined, trusting in a kind Providence, to work

acter, situation and circumstances, capacities and

his own way through life; to rely on his own exer-

powers among mankind. A wise and good Provi-

tions, to receive no favours but what his labours

dence has committed to every one talents, which,

would afford him; and even then, he did believe

if rightly improved, will lead them to peace and

he should succeed in the race with his young

hope in this life, and to a state of exalted and en-

friends,--an in a few years, be enabled to lead

during happiness in a brighter and better world.

instead of follow.

William, when he started in life had no father to

care for him ; his mother was a widow and poor,

This hope was realized from year to year, his path

and when she married a second time, her husband,

was always progressive, notwithstanding the occa-

from a variety of causes, was unable to guide or

sional trials he met with. By his own exertions

even to assist William to commence life with

he could afford himself rational enjoyments, and

advantage. There were different grades in society

had reason to be grateful that he so far succeeded

then, as there are now. Two or three families in

as to be able, through life, to meet all the reason-

a large town were esteemed rich the remainder,