From collection Creating Acadia National Park: The George B. Dorr Research Archive of Ronald H. Epp

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

Page 62

Page 63

Page 64

Page 65

Page 66

Page 67

Page 68

Page 69

Page 70

Page 71

Page 72

Page 73

Page 74

Page 75

Page 76

Page 77

Page 78

Page 79

Page 80

Page 81

Page 82

Page 83

Page 84

Page 85

Page 86

Page 87

Page 88

Page 89

Page 90

Page 91

Page 92

Page 93

Page 94

Page 95

Page 96

Page 97

Page 98

Page 99

Page 100

Page 101

Page 102

Page 103

Page 104

Page 105

Page 106

Page 107

Page 108

Page 109

Page 110

Page 111

Page 112

Search

results in pages

Metadata

[Series III] Acadia National Park, The Founders-Dorr, Eliot, JDR Jr.

Acadia National Park :

The founders-DORK,ENOT, JDRJr.

Bryan, John

Art Department

U.R South Carolina

803-777-4236

The

Founders

Since the formation of the Sieur de Monts National Monument, varied views have

been offered regarding the relationships between park Founders.

Many published accounts have stressed qualities of George B. Dorr, Charles W.

Eliot, and John D. Rockefeller Jr. that were incompatible with their partners in the

establishment of Acadia National Park; others focused on shared character traits.

It is also possible that their conservation achievements were the product of an

antagonism that may or may not have been acknowledged.

This file offers a sampling of their character traits both as seen by others and at

times by the Founders themselves. Mount Desert Island historian Judith S.

Goldstein refers to this threesome as "the Triumvirate," a term that-given its

classical historical associations--may have made one or more of the Founders

uncomfortable.

Contained therein is a paper I delivered at the Jesup Memorial Library that

emphasized the commonalities of the Founders. A central argument is that for

patrician males born during the arc of mid 19th-century America, their novel use

of emotional language suggests a degree of intimacy that may reflect a deeper

reservoir of shared character traits than what is reported in the historical record.

Ronald H. Epp Ph.D.

2021

BOIAM2S

send

2161

I

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

som

STATE

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

WASHINGTON

Bar Harbor, Me., Oct. 29, 1917.

Mr. Horace M. Albright,

Acting Director National Park Service,

Department of the Interior,

Washington, D. C.

Dear Mr. Albright:

I want to add just a word about the development of the

Park.

People are taking great interest in it, not only the

people here but in a very wide circle. If I can show results

within the next few years and what it may be made to mean to

a great public, that interest will grow and bring its own re-

sults in turn. If it stays inert, not opening out and

developing its points of interest, its opportunity to give, ,

that interest will drop.

It is extremely important for the Monument that I should

be able to secure certain noble frontages I have in mind upon

the ocean. For bringing this about I am dependent on the

interest aroused, for they will be costly; but they are not

out of reach if that interest can be kept quick and moving.

The development here has got to be what we call in agriculture

'intensive', calculated to bring a large return from a

relatively limited area. The Monument lends itself to this

remarkably. There will be scarcely a hundred acres in a

single tract in the whole Monument that will not be fitted to

2.

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

WASHINGTON

make its own contribution of interest or beauty, different

from the rest. And the landscape effects I am planning for,

and am already in part securing, are unique -- in the world

SO far as I know -- and singularly striking. This is due

to the boldness of the Elaciated rock formation and the

picturesqueness of the foregrounds made by the frost-split

granite, covered with moss and lichens. And it is also due

to the character of the vegetation, which leaves no bareness

anywhere and is rich in northern forms. In this it is un-

like the White Mountains, which are relatively bare in

detail, and unlike any of our southern landscapes.

The park, with such a path system as I am planning and

have got already started, with its woods and springs and the

ocean presence, ought to become one of the great health

resorts as well as recreative areas of the country. It has

remarkable possibilities in that direction, needing only

proper hotels and a few years development of the park to make

it so. And it is capable of being made as well a great

biological station, exhibiting in & concentrated space the

flora and fauna of the whole northeastern region of the

continent. People are taking great interest in this aspect

of it also, and I ought to be able to Secure generous support

for it on this ground as well, when I can show results.

I calculate there are now about ten thousand acres in the

Monument with what I now have ready to add to it; I hope to

3.

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

WASHINGTON

make this twenty thousand presently including in it something

like thirty square miles. This will take in the whole moun-

tain range and its adjoining valleys, together with good

wharfages and sea approaches, and a considerable extent of

shore.

On the historic side, keeping alive the memory of a

singularly interesting period in the settlement of the country

and of the part France took in that settlement, the Monument

has a distinct mission. It can enrich the national life

with memories and associations we have been losing sight of.

This back-ground of history, I find, interests everyone

who comes here very greatly and is already becoming through the

Sieur de Monts Publications a feature of the Monument. I have

these publications on distribution at two places, the Govern-

ment office and at the Sieur de Monts Spring entrance to the

Monument, of which Secretary Lane can tell you. It interested

him more, he told me as he was going off, than any other thing

he saw here, in its combination of the wildness of nature and

the human touch. There, opposite the entrance to the Emery

path which leads to Sieur de Monts Crag and on over Dry Mountain

to the Island summit, I have placed a simple little building

sixteen feet square with & sanded floor and with a round oak

table I gave for the purpose in the middle; the Crag looks down

on it. On the table these publications are kept, spread out,

and the door is open. A constant stream of people already

passes there in summer time and carries off these pamphlets. It

4.

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

WASHINGTON

has become, from a seemingly remote and unfrequented spot one

of the most frequented spots on the Island within the last two

years, it being first opened to the public on the creation of

the Monument.

Placed where the Monument is, with its railroad, motor,

and water connections -- and air connections doubtless present-

ly -- it is bound to be a point of great resort in the future,

as it is developed and takes on a park-like aspect. Villa

residence is already occupying the shore as far as the

Penobscot, in practically unbroken occupation. The time is

not distant when the park will present the only trect of

really wild land upon the whole coast. The problem is, as I

stated in my paper, to maintain its atmosphere of wildness

and of natural beauty in the presence of the many thousand

people who will annually visit it.

Another matter I am studying over now is to make resort

to it inexpensive, so that people of moderate means or on

salary can come to it freely. This is a matter that I talked

over with Mrs. Lane when she and Secretary Lane were here,

I can get people boarded now at not exceeding fourteen dollars

a week, and this is the first year -- owing to war prices --

when it would have been as high. But to provide for people

at such rates on a large scale new accommodations will have to

be provided, and it is this question, of location and the cost

of building, which I am working on. The railroads will make

special rates for such visitors to the park, I have ascertained.

5.

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

WASHINGTON

So will the steamboat lines.

With regard to food supply, the conditions are extremely

favorable if the supply be properly organized. The supply

of fish from the ocean, bought direct from the fishermen, is

abundant and cheap. It is also a luxury to those who do not

live within reach of it at other times. The market-garden

industry also has sprung up now to such an extent in this

region, stimulated by summer residence and the advent of the

motor, that farmers fifty miles away -- in the neighborhood

of Bangor -- club together and send a motor down two or

three times a week, while the neighboring farmers, on the main-

land as well as on the Island, make daily trips.

Boat freight from Boston and Portland is also low and can

be used for anything which is not quickly perishable. And

as

soon as people know what can be counted on in the way of

demand there will be no difficulty in providing for people

inexpensively on a large scale. On a lesser one they can be

cared for now in the park's immediate vicinity. For the

park is surrounded by resort and fishing villages, placed

upon the shore. And every natural condition is favorable

to low prices, cheap transport and good food.

Yours sincerely,

G.B.Dosr

Thrumphi

UNITED STATES

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Rample 3

REGION THREE

H.P.S.

SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO

4.5 Can't

January 19, 1942. Sarta

Mr. George B. Dorr, Superintendent,

Acadia National Park,

Bar Harbor, Maine.

Dear Mr. Dorr:

I have just read, with highest satisfaction, the Service news re-

lease for Sunday, January 11, signalling the virtual completion of your

plans for enlargement of Acadia National Park, culminating nearly a

half century of effort devoted to its creation, planning, development,

and enlargement.

Many years ago at Mesa Verde National Park, Mr. Rockefeller, Jr.,

told me, in intimate detail, the story of your conception for preserving

for the nation a superb area of the coastlands of Maine--the story of

George B. Dorr and Acadia National Park. He said that his long friend-

ship for you, your diligence and devotion to the cause, your courage in

the face of expressed opposition of long entrenched wealthy residents,

and your gifts of property beyond your ability to give, had stimulated

his desire to "chip in" and assist you in the realization of your ideals

for the Service and the nation.

One who has worked diligently through more than a third of a cen-

tury to advance certain plans and ideals in Mesa Verde National Park,

likewise endorsed and generously supported by Mr. Rockefeller, Jr.,

congratulates warmly the patriarch of our Service, on realizing his

ideals and objectives for Acadia National Park.

May health, happiness, and enjoyment of the fruits of your fore-

sightedness and diligent effort comfort you through the years that lie

ahead.

Sincerely yours,

Jurse Lundbaum

Jesse L. Nusbaum.

Sevin archaeol

Region U.S. Counthouses 3, n.c. jental Iii A.M

UNITED STATES

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Acadia National Park

Bar Harbor, Maine

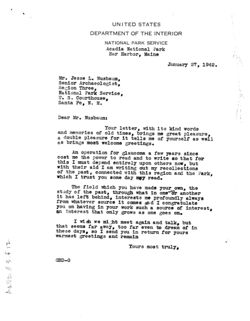

January 27, 1942.

Mr. Jesse L. Nusbaum,

Senior Archaeologist,

Region Three,

National Park Service,

U. S. Courthouse,

Santa Fe, N. M.

Dear Mr. Nusbaum:

Your letter, with its kind words

and memories of old times, brings me great pleasure,

a double pleasure for it tells me of yourself as well

as brings most welcome greetings.

An operation for glaucoma a few years since

cost me the power to read and to write ao that for

this I must depend entirely upon others now, but

with their aid I am writing out my recollections

of the past, connected with this region and the Park,

which I trust you some day my read.

The field which you have made your own, the

study of the past, through what in oneway another

it has left behind, interests me profoundly always

from whatever source it comes and I congratulate

you on having in your work such a source of interest,

an interest that only grows as one goes on.

I wi sh we might meet again and talk, but

that seems far away, too far even to dream of in

these days, so I send you in return for yours

warmest greetings and remain

Yours most truly,

GBD-0

Bluffs

ACADIA

Dedication of Cadillac Mountain

Road Completes Fulfilment of George

at in-

arious

A Boyhood Dream

Bucknam Dorr's Life-long Mission-

Devoted to Preservation of Mount

have

The

Come True

Desert's Primitive Beauties.

ology,

e par-

By B. MORTON HAVEY

ouglas

aterial

T

HE history of a nation was changing. A chapter

ine of

long since been passed down to us by parents and

of war was passing into the shadow.

Island

grand-parents.

But the ogre of reconstruction-with its trials

ich, in

Our first picture of Mount Desert, in truth, is all that

and diversities-beckoned its unfortunates to come; to

had been visioned-and more!

pass over the grill of turbulence, which is the aftermath

Gate-

of strife between countries and peoples.

Our first inspiration-and it is still in the years of

th the

youth, you will remember-is to lend the hand of man

nning,

Is it to be wondered that at such a

to the great task of conserving all

Abbe,

time in the affairs of our United

the fine things before us, passing

ory of

States a quiet isle off the coast of

them down to posterity for pos-

Walter

our own State of Maine should, in

terity's sake alone.

show a

its very solemnity and peace,

It is the work of a life-time!

ge an-

carry impressiveness and in-

Are we decided?

rst in-

spiration?

Can we devote our life, mind

istance

Is it to be wondered that this

and body, to this vast under-

ren K.

bit of land-l'Isle des Monts

taking? Can we educate our-

deserts--its mountains silent in

selves for this single purpose?

1 Park

primeval sleep, should summon

With this single objective in

val, its

anew thought of centuries

view? Can we make an actu-

e first

past: Black-robed priests

ality of this wish of our

in romantic guise,

forebears?

steeped in learning,

It is an inborn ex-

paled from

pression of the soul-

monastery vig-

as determined, as self-

the art

ilance, passing

sacrificing, as relig-

I 1921,

in the night

ke, by

iously con

among plumed

autiful

ceived, devoid

helmets cast

m that

of all ego, as

aside by weary

county

is the thought

men, whose

by the

of those black-

fondest hope,

al Bu-

robed men of

whether lord or

e high-

years ago,

vassal, could

casting about

be to give

remely

in the forests,

their

lives for Mr. Dorr and Franklin K. Lane, former Secretary of The Interior, photographed at

le, for

in priestly y

France.

summit of Cadillac Mountain when the new road was being planned.

olds an

vestment, by

t parks

Let us slip back a moment, across the years, into those

the flickering lights of their ghostly camp fires!

of the

days of drab, bleak reconstruction.

We are resolved!

evement

In youth, then, we leave other quarters of the country

-leave riots, dishonesty, horrors and gruesome scenes

George Bucknam Dorr

-to come to peaceful Mount Desert.

To try and visualize the work and the inspiration of

The story of its sleepy mountains, reaching their

George Bucknam Dorr is difficult. A man now well be-

at rail-

slopes into the restless ocean, adorning their tops with

yond his three score and ten years, Mr. Dorr talks but

ngineer.

characteristic pines and hemlocks, picturing, in them-

little of himself; if you would see his life's work-for

heel.

selves all that is strong and beautiful in Nature, has

(Continued on page 29)

Page Eleven

2

MAINE HIGHWAYS

29

in

ACADIA A BOYHOOD DREAM

him a day, note his activities and pleasures-most all of

(Continued from page 11)

which are akin to work-and you can't help from re-

away con-

which he seeks no personal glory-you have but to gaze

turning with a lighter step and in a happier frame of

traveling

mind.

immission,

on and visit Acadia National Park.

Incidentally (and we feel that is the proper word),

He radiates those qualities, talks on any subject you

Macadam.

he is Superintendent of the Park; is briefly rated as

wish, writes and reads in eight languages, spends his

into city.

such, together with being its founder, in Who's Who In

evenings translating from the original Greek, makes

sent pave-

America.

haste when there is need-but has a most enjoyable

habit of not making too much haste!

Who's Who, further, tells us that Mr. Dorr is a stu-

Gravel.

dent, scientist, born in 1853; an unmarried man; also

And now your patience is requested for a moment

niles

indicates that he is well educated, has devoted much

while we go into the 'first person' part of this account.

Alternate

time to plant life, public reservations and landscape

Reportorial Tactics--and Comebacks

mariscotta

gardening.

On the day I interviewed Mr. Dorr warning was given

Travel al-

That is not exciting or particularly newsy: You

by friends that he would talk for hours on the subject

would just naturally expect it, take it all for granted,

of Acadia National Park-but that I had best watch out

d around

after meeting the man. You would know that he set

if any attempt was made to lead him onto the subject of

ituminous

out on a purpose in early life, trained his mind for

George Bucknam Dorr.

what he had to do, denied himself many privileges and

"Unfortunately, what is it you wish to discuss?" he

Macadam.

pleasures to give his undivided time to the labor ahead.

greeted, with a smile, having an inkling of what my call

posite di-

The nearest he comes to telling you that, in substance,

was all about.

5 miles-

or anything else regarding himself is, in his own words:

"Unfortunately, I would like to know a few things

"The impelling causes of what people do may gen-

about George Bucknam Dorr," was my reply.

lous Mac-

erally be found far back. What led to my own interest

"Very well," he returned, much to my surprise, and

alternate

in nature and landscape, in their conservation, and in

immediately began telling me about the beautiful hills

ou.

sharing the pleasure got from them with others came

and view thereabouts.

from years of close association, both abroad and in this

It was finally realized that he was evading the point,

country, with my father and my mother, who inherited

so, as tactfully as possible, the conversation was swung

in turn from older generations."

to the personal side once again.

"Oh, yes, to be sure, you desire) to know about George

For One And All

Bucknam Dorr," he said-with apologies for using the

E

Acadia National Park is a spot for all. Classes of

quotation marks-it was simply something like that.

people, regardless of station or position, may come here

Nevertheless, my hopes were raised as he left the room

and take away enjoyment and happiness far and beyond

a moment, to return with an old family house-book.

the realm of monetary value.

Turning the pages, he finally came upon an original

And neither, curiously enough, has Mr. Dorr made nor

poem, written in pen and ink, by Oliver Wendell

attempted to make a monument to himself or family

Holmes.

from Acadia National Park. The development has been

"Would you just read that?" he invited.

his life-time's work, but he is wholly satisfied, for his

Very thoroughly I read the lines, believing that he

part, to accept in payment the knowledge that he has

was to tell me a story of his life, which, perhaps, had

done something for others; that he has given some-

an association with this verse.

thing instead of taken something.

Hide and Seek

Many have assisted him, contributed priceless efforts,

About ten or fifteen minutes later I found him at his

but for this brief article, their magnanimity is sought

desk in another room. He greeted me with a smile,

that exclusive lines may be devoted to this man, now in

took the house-book for a moment, turned to another

the sunset of life, who may gaze upon 'his' beloved hills

VERY

of Acadia and find there carved the achievement of an

page and invited me to read another bit of verse.

T OF

I was most happy to do so, especially in the thought

inherent custody.

that it was bringing me closer to the information I

AND

A Kindly Man

sought.

URS

Mr. Dorr is a kindly man; ever a gentleman in every

After the second reading was completed, I discovered

deed and act.

that Mr. Dorr had disappeared again. About ten

He has a merry twinkle in his eye, a good color in

minutes later I found him, working as usual. Just as

his cheeks, the kind of a laugh you're bound to like, a

though he wished to groom me further he said:

lot of wit-and loves a prank. He makes you feel that

"Come and I will show you about."

Mass.

advanced age cannot be so serious after all! Visit with

He did-but still said nothing of himself.

3

30

MAINE HIGHWAYS

"No, no!" I almost shouted. "I just want to talk

with you, if you please."

"Oh, but you should see the mountain," he replied

Tarmac

with that same politeness and smile.

was

"But I've seen it a thousand times," I protested.

Pul

MAKES GOOD ROADS

"But you must see it again," he insisted.

ma

Before I could do any more insisting, I was hustled

pro

into a car, and as it's said: taken for a ride! And I

age

spent the remainder of 'my interview' looking at scenery

T

from the mountain tops while Mr. George Bucknam

hig]

Dorr-I'll wager a cooky-chuckled, as he worked in

com

his modest little study in the foothills, because he had

rou

outwitted another reporter!

Stat

Honored by Congress

con

It is quite generally known that Mr. Dorr has been

as

paid a distinct honor by Congress. His work was ap-

the

preciated to the extent that the Federal government

inte:

passed a special bill allowing him to be retained as

poir

Superintendent of Acadia National Park, after he had

quir

reached the age of retirement.

term

Koppers Products Company, Inc.

There are many intimate facts regarding his life and

gene

public career which pass from mouth to mouth; which

brid

Providence, R.I. - Boston, Mass.

should be written, that this man might receive the fullest

toge

Distributing Plant - Portland, Me.

credit for his accomplishment.

pose

But if one wishes to be exact, he must gather the ma-

refer

terial for such an account from Mr. Dorr, and Mr. Dorr

mon

alone, and as yet he does not feel it necessary or ex-

Whe

pedient to associate his own personality with Acadia

mate

Finally he reached upon the mantel, removed a

National Park.

mitte

glass vessel which contained a fine sand; walked over

He is satisfied and happy to carry on the work of his

ticula

close by the light of a window. At last, I thought, he is

fathers for the enjoyment of humanity.

and

going to give me some personal information! That

plans

sand, I was sure, came from the rock on the top of

trict

Mr. Barrows Attends n. y. Meeting

Cadillac-and who knows but what it represented his

to su

Chief Engineer Lucius D. Barrows. who is Vice Presi-

initial inspiration in behalf of this Park?

Publi

dent of the Association of State Highway Officials of

"See how fine it is," he said, as he allowed a bit of

A

the North Atlantic States, attended a meeting of the

the contents of the jar to stream into his hand.

struct

directors of that organization, held in New York on July

"Yes, yes!" I agreed with genuine enthusiasm.

repre

15th.

He carefully placed the jar back upon the mantle.

Depa

The purpose of the session was to determine the lo-

"From the rock on Cadillac?"

the te

cation of the annual convention, to be held in 1933,

"Oh, no," came very casually, as he set about moving

proje

Atlantic City being selected.

some papers here and there. "Banks of the river Nile!"

to sul

work

He Wins the Day

requir

It was then lunch time-and I hustled through the

The BOND Co.

of the

hour, with cooperation from Mr. Dorr's efficient secre-

Vou

tary, Miss Oakes, who realized the task I had buckled up

HAROLD L. BOND, Pres.

progro

work

against.

I wondered just how long this gentleman could so

DEALERS IN TOOLS AND EQUIPMENT FOR

The

courteously, but efficiently, avoid my direct questioning.

CONSTRUCTION WORK

partm

I wanted to be a good cross-examining lawyer

Burea

for about fifteen minutes!

39 Old Colony Avenue

South Boston

is Tho

"Miss Oakes," came a pleasant command. "Will you

trict N

Telephone South Boston 0764

see that this young man is given a ride up over the

the su

mountain?

resente

W.

Olson, 'N Kent. "Second Founding,

First Light : Acade c Vahl Pah ad

that Pisut Islad. Photography &

Tone Blagden, To. Text 2 Charles

R.Tyson Jr. 2003 Sp. 6-10

Englised CO : Wes cliffe Publishers

"If the Yorkees who corrected of Acadie

had waited for Caypen to wate th

selfsane park it tonever worl d

have happened. The percepted ferenda

then Joh D. looffeller Jr. (chief lad down

ad francist hader), Hawad colly

President Charle weliot (philosophy thing

of fle pashides) ad the tireless

Tayer Don (herefactor trend par

capitated ). Then are out Men

who dallied Dorr who ex alled

at political tactics, devated

had f he life x furth to assembling

the pah l taby or the indifferent

ad the opposed He worked a

tepid Ceripien ad heat a Main

legislators attaupt to stup the

HCTPR, Maries first lad trust,

of the ability to hold donated

pack could h obtableted , (p-8)

propertyes for free untre the "

+ " Quarte initiative govern Acadia."

2

'l morrel at how virlonary the packs

forder were. Assebly Audic was

an immense act of gift giving

bullah consent politics , & franget,

place in a time when "awesome" had

informed y a powerful reverence for

a meaning The pach wa a land

planny decompleted of matiousire

significance perfectly timed urthin llarie,

"Auder was needs to lender a place

apart."

576

Barrett Wendell.

[June,

1921.]

Alfred Tredway White.

577

sacred to him because he made it. Rather he suspected it both to be

less than what people declared it and less than he wanted to believe it.

ALFRED TREDWAY WHITE.

Something of the Puritan in him, combined with this modesty, led

him to the decrying of his own work as a teacher of composition.

Br FRANCIS G. PEABODY, '69.

Training himself relentlessly to face facts, and noting in our colleges

the enormous expenditure for training in English as compared with the

A

LFRED TREDWAY WHITE (A.M. hon. 1890) died January 29,

1921. He had set out, as was not unusual with him, on a tramp

literary output or even widespread correctness of usage, he sometimes

among the mountains of the Ramapo region west of the Hudson River,

queried our whole system, and naturally his own work as a part of it.

and, while skating on one of its numerous lakes, broke through the

To people who could not understand this impersonality of attitude,

ice and was drowned. The immediate circumstances of the accident

all this seemed a pose; but it was not.

made it a grave shock to his friends; but sudden death, in itself, com-

Born and bred a conservative in social matters, he reorgan-

ing to a man of seventy-five, in the fulness of athletic vigor, and with

izer intellectually. Steadily, his life long, an inculcator of that which

an unblemished record of integrity and beneficence, cannot be re-

is deadliest to conservatism, - independent, fresh, constructive

garded as untimely or deplorable. Mr. White's death was mourned

thinking, - he was one of the most stimulating teachers Harvard has

by the people of Brooklyn as that of their best-loved neighbor and

ever known. Perhaps his greatest gift to his pupils, particularly

leading citizen, and a Memorial Meeting at the Academy of Music

those who became teachers, was the creation of an attitude toward

brought together rich and poor, Catholics and Protestants, white and

their work. He made them see the students, not as buckets to be

black, in a unanimity of affection, and with a sense of public and per-

filled, but as individualities to be descried. The college age is a

sonal bereavement, which few private citizens in the diversified life

time when ambitions are high, but students, still timorous as to

of a great metropolis, have inspired.

whether they can make real their dreams, cannot talk of them freely.

Mr. White was the son of a merchant who, with his brother, estab-

Inestimable to them is a teacher who, treating them not as groups,

lished, in 1839, the firm of W. A. & A. M. White in New York. The

but as individuals, competent to judge and fearlessly honest, helps

son was trained to be an engineer and received the degree of C.E. at

them to see that ambition is not always endowment or that he descries

the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute of Troy in 1865, when nineteen

signs that the dreams may, with exacting, unremitting labor, be ful-

years of age. He was the valedictorian of his class. After a visit

filled. Yet always Wendell set the art higher than the individual

to Europe he entered business life in his father's office and soon be-

and never let his praise of the accomplishment leave the writer in

came a partner in the, firm. Mr. White's instincts and ideals were,

smug satisfaction that his utmost goal had been reached. It is a very

however, not those of a merchant or financier. He concerned him-

fitting thing which the Sorbonne has done in honor of Barrett Wendell,

self at once with the philanthropic and economic needs of the rapidly

placing his name above one of the portals of the Department of Eng-

growing city of Brooklyn, and soon became a trusted leader and coun-

lish, for the intellectual life of many a Harvard graduate is the richer

selor. With his cousin, Seth Low, he organized the Brooklyn Bureau

for the doors he opened in undergraduate days.

of Charities in 1878, and was its president for thirty years. He be-

came a director of the Brooklyn Children's Aid Society in 1868, and

was intimately concerned with its affairs for fifty years. His obser-

vation of conditions in Brooklyn soon convinced him that poverty

Hanard Graduates Magazine

and disease were intimately associated with the housing of the people,

and that better living must begin in better homes. Housing reform

had not as yet been seriously undertaken in the United States, and

no satisfactory precedent could be studied. Mr. White, therefore,

when but twenty-nine years old, sailed to England, inspected Sir

Sydney Waterlow's buildings, and other illustrations of model dwell-

(29/(1221):577-83.

On

578

Alfred Tredway White.

[June,

1921.]

Alfred Tredway White.

579

ings, and, returning to Brooklyn, built, near the waterfront, the most

notable block of improved tenements undertaken, at that time, in

Social Museum, until the total of these benefactions reached nearly

the United States. "The problem that shaped itself in my mind,"

$300,000. "I believe," he wrote to President Eliot in 1903, "that the

he wrote in 1875, "was, what is the best. accommodation which can

interest in the study of the Social Questions will broaden if the facili-

be given to the poorest paid of the working-people, at the price which

ties for such studies be increased, and I shall be glad to aid in making

they are accustomed to pay, and which would permit a fair return on

such provision at Harvard as may perpetuate, expand, and dignify

the investment, while furnishing sun-lighted rooms, domestic privacy,

the course already established"; and again, to President Lowell in

and freedom from fire." The Tower Buildings, erected in 1877-79,

1917, "While I sympathize with the desire to provide instruction

on these principles, contained 267 lettings, and the Riverside Build-

especially designed for Divinity School students, I would also keep in

ings, built in 1890, 280 lettings, or a total in both blocks of 547 homes,

mind the interests of that large body of undergraduates who, as likely

housing about 2000 tenants.

to become men of affairs, should realize the fundamentally ethical

This bold enterprise, undertaken through the private initiative of

nature of many of our social problems." For more than ten years

one young man, has remained for forty years a model for similar

these gifts were, by Mr. 'White's explicit direction, recorded as anony-

enterprises. Fireproof construction, separate entrances, outside stair-

mous, and it was not until a new professor took command of the De-

ways, sun-lighted rooms, interior parks and playgrounds, and rebates

partment that the source of this stream of benefactions was generally

on prompt payments - the conditions which Mr. White at once en-

known to be, not a graduate of the College, but a remote and unsus-

pected friend.

forced - have been accepted as essential, both for health and for

profit. His buildings have been eagerly sought for by desirable ten-

It is not necessary to enumerate here in detail the varied enterprises

ants; the death-rate, both of adults and children, has been reduced;

for civic and social service which endeared Mr. White to his own

and the commercial return, through this long term of years, has been

community. He was Commissioner of City Works in 1893--94 under

satisfactorily maintained. Helping the low-wage working-man, Mr.

a reform administration of Brooklyn, and excited the most determined

White said, did not make him poorer. No taint of patronage has been

hostility from contractors and politicians, whose schemes were con-

felt by occupants. The philanthropic motive was disguised by the

fronted by his impregnable integrity. At the end of his term, how-

business administration. As a consequence of this pioneer under-

ever, he received an emblazoned testimonial, commending his admin-

taking, Mr. White became a member of the Tenement House Com-

istration and signed by the very men who had opposed his reforms.

mission in New York in 1900, a director of the City and Suburban

During this period of public service he was responsible for the building

Homes Company, and a trustee of the Russell Sage Foundation.

of a Public Market, and its clock-tower represents his salary, - and,

Out of this epoch-making venture grew Mr. White's association with

probably, much more, - as returned to the treasury. He was a

Harvard University. He had heard that his buildings were material

passionate loyer of flowers, and this taste led him to increase the en--

for observation by students of social ethics, and he conceived the idea

dowment of the Botanic Garden of the city, and to create there one

of making the way of social service easier for others than it had been

of the most lovely of Japanese gardens, with its characteristic lake,

for him. It was necessary for him. he said, to cross the ocean for

bridges, dwarfed trees, and rock-effects. He was an untiring friend

instruction, and to proceed without expert guidance. Might not

of Negro Education, providing Hampton Institute with & special

young men like himself be taught, while in college, to use their lives

fund, and, together with other members of his family, erecting at

Tüskegee Institute a building known as White Hall. He was a

and means more efficiently for the public good? With this hope he

proceeded, first, to contribute $50,000 to secure the erection of Emer-

member of the first executive committee of the American Red Cross

son Hall, providing that in this building space should be assigned to

as organized for the World War, was decorated by the King of Serbia

the Department of Social Ethics; and then, through successive gifts,

for his gifts to that country, and received from the King of Belgium

to strengthen the Department by endowment, together with special

the Order of the Cross. Each month, from the beginning of the war,

gifts for furnishings, publications, and illustrative material for the

a special contribution was forwarded by him to Cardinal Mercier,

who, on learning from a Brooklyn priest the name of this anonymous

580

Alfred Tredway White.

[June,

921.]

Alfred Tredway White.

581

benefactor, sent him a precious crucifix from his own table. Such are

a few of the undertakings with which his name is associated, and which

White was a distinguished example. He had, among other gifts,

have led his fellow citizens to commemorate his wise generosity by

he faculty of prevision. Precisely as the maker of money must an-

placing a memorial tablet in the beautiful Botanic Garden which he

icipate.: needs and foresee what course events are to take, so the giver

was principally instrumental in establishing.

if money should be endowed with a constructive imagination and a

No one can review a career like Mr. White's - modest, beneficent,

ane foresight. His happiness, like that of the enterprising financier,

and judicious - without being led to some reflections on the uses of

S in developing unsuspected resources and anticipating unrecognized

wealth and the secret of efficiency. This kind of life is, in the first

yants. Like Wordsworth's "Happy Warrior," he,

place, the best defence that can be offered for the present system of in-

Through the heat of conflict, keeps the law

dustry, which encourages private ownership. The so-called capital-

In calmness made, and sees what he foresaw.

istic system is manifestly under trial. Agitators and revolutionists

affirm that it degrades the possessors and wrongs the dispossessed;

Mr. White's service to Harvard University illustrated this application

and there are instances enough of the misuse or waste of surplus capi-

of business prevision to the distribution of wealth. When he began

tal to encourage the advocates of confiscation or of communal control.

o invest in the Department of Social Ethics, one of the most trusted

The trouble with the rich is apt to be, not that they have money, but

members of the College faculty remarked that he did not see how such

that they do not know what money is for. They have learned how

ctudies could be seriously pursued. Mr. White regarded this scep-

to get, but have not learned how to use. The development of the

icism with good-humored indifference, He was, he said, perfectly

prehensile grasp has involved an atrophy of the open palm. Their

ure that the problems of social and industrial change, or, as Mr. Rob-

wealth has become what Ruskin called their "ill-th." If, on the

rt Treat Paine announced in establishing his fellowship, "The

other hand, a rich man regards himself, not as a possessor, but as a

fforts of legislation, governmental administration, and private philan-

trustee; if, instead of owning his wealth he is conscious that he owes

hropy to ameliorate the lot of the masses of mankind," must be "the

it, - then his distributions and benefactions are likely to be more

entral matter of interest for educated young men during the next

judicious than the schemes of politicians or the judgments of less

fty years." He proceeded, therefore, to endow the first systematic

competent men. The same discretion and discernment are applied

nd academic instruction in these subjects which this or any other

to giving which have been utilized in getting, and the world is the

country had maintained; and the eager and even passionate desire

better, not only for the money received, but for the sagacity with

low so generally manifested among college students to have some part

which it is distributed. In other words, the system of private owner-

a the making of a better world, amply verifies Mr. White's prevision.

ship is a stern test of character. It calls for conscience as well as for

The same anticipation of needs characterized much of his giving.

capacity. Ownership involves obligation. Service is the only free-

l'ew citizens of Brooklyn could have imagined what pleasure was to

dom. Mr. White met this test. He lived with personal simplicity,

ie derived from a Japanese garden, but it has revealed to thousands

and his life, service, and property were trusts for the common good.

if old and young a type of beauty of whose existence they had not

In conferring an honorary degree on him, in 1890, President Eliot

lieen aware. His gifts to Belgium anticipated by many months any

described him as "virum recte divitem esse scientem." He knew how to

general sense of responsibility in this country for the sufferings of that

be honorably rich.

;allant little land. In December, 1920, there arrived in this country

To justify this way of life, however, more is needed than good in-

representative of the ancient churches of Transylvania, which had

seen crushed almost out of existence under Roumanian rule. What

tentions. (The administration of wealth as a trust calls for personal

qualities which are quite as rare as those which ensure the acquiring

vas this visitor's surprise to learn that, before he had reached this

of wealth. Distribution may be as profitless as hoarding. Invest-

country, one anonymous American had, of his own volition, trans-

ment in philanthropy calls for as much sagacity as investment in

:aitted repeated and generous gifts to these remote sufferers. Most

securities. Of these higher qualities of the distributor of wealth, Mr.

;ivers of money wait until, among the multitudinous calls for help,

their contributions are invited. A demand is thrust upon their atten-

582

Alfred Tredway White.

[June,

1.]

From a Graduate's Window.

583

tion, and they surrender to it. The wise user of wealth devises new

erosity was the natural flowering from a deep-rooted and daily-

ways of service, and foresees unrecognized needs. He adds to gener-

cred religious life. The secret of his happy and beneficent activity

osity prevision. He has not only an open heart but an open mind.

in his early discovery and continuous assurance of the life of God

A still rarer trait in the philanthropist is persistency. Much giving,

he soul of man.

even by generous citizens, is occasional, spasmodic, and transitory.

The object is temporarily interesting, but one soon passes to the next.

It is said that the average duration of loyalty to a relief association

is not more than five years. The enterprises which Mr. White guided

and reenforced are perhaps more than all indebted to him for an in-

domitable persistency. Having once assumed an obligation, no vicis-

situde disheartened him, and no impatience made his devotion slacken.

It was one thing to organize a Bureau of Charities in Brooklyn, but

it was quite another thing to watch each detail of administration, and

refresh an exhausted treasury, during a long term of years. It was

an interesting venture to endow a Department of Social Ethics, but it

was a much severer test of character to be the anonymous source of

a continuous stream of benefactions for nearly twenty years, and to

secure their continuance after one's death. To take up with new

causes is exhilarating, but to maintain causes where romance has been

lost in routine calls for the rarer gift of persistency.

"Iustum et tenacem propositi virum

non civium ardor prava iubentium

non voltus instantis tyranni

mente quatit solida," -

the praise which Horace gave to his ideal statesman, might have been

written of Alfred White. The upright man holds on to whatever he

undertakes.

These gifts of prevision and persistency which marked Mr. White's

administration of wealth were fortified and sustained by a still more

commanding habit of mind. It was a rational and lifelong faith in

the Divine guidance of the individual and of the world. Behind a

manner of sunny and unassuming kindliness, which made him a

delightful companion, were the firmness, detachment, and serenity

which were derived from the habitual dedication of his life to accom-

plish, not his own will, but the will of Him who sent him. His reli-

gious life was uncomplicated and unclouded. Neither domestic sorrow

nor public controversy could disturb his tranquillity or self-control.

He directed his daily affairs as ever in his Great Taskmaster's eye. It

was this habit of faith which led him straight to works of love. His

social service was the corollary of his Christian consecration. His

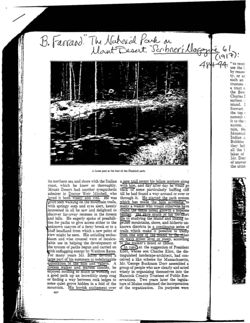

B. Farrand "The National Park on

Mount Desert. "Scribner's llagantie 61

(1917)

484 94.

to recei

use the 1.

by reason

tv, or ar.

such an

trustees

a tract O

the Bow

Charles I

earliest

island. I

Stewart

the top

summit

it to the

nation.

tain, the

Mountai:

Indian

Bubbles

they hel

all the

1

lakes of

Mr. Dorr

of unswer

the ultim

A forest pool at the foot of the Diedrich path.

its northern sea and shore with the Italian

a new trail swept his fellow workers along

coast, which he knew so thoroughly.

with him, and day after day he would go

Mount Desert had another sympathetic

back to some particularly baffling cliff

admirer in Doctor Weir Mitchell, who

till he had found a way around or over or

loved it both wisely and well. He was

through it. He started the path system

often seen walking on the mountain trails,

which has made the hills accessible to

with springy step and eyes alert, keenly

many a walker who would otherwise have

interested in all he saw and delighted to

found the dense forest growth a hopeless

discover far-away recesses in the forests

barrier. He gave much of his too-short

and hills. He eagerly spoke of possibili-

life to studying the island and linking to-

ties for paths to give access either to the

gether mountains, shore, and hitherto un-

unknown canyon of a ferny brook or to a

known districts in a continuous series of

bluff headland from which a new point of

trails which make it possible to tramp

view might be seen. His unfailing enthu-

from one side of the Island to the other

siasm and wise counsel were of incalcu-

on wavs either level or steep, according

lable use in helping the development of

to the walker's mood or choice.

the system of paths begun and carried on

In IDOI at the suggestion of President

with unflagging energy by Waldron Bates.

Eliot, whose son Charles Eliot, the dis-

For many years Mr. Bates devoted

a

tinguished landscape-architect, had con-

large part of his summers to indefatigable

ceived a like scheme for Massachusetts,

exploration of the hills and vallevs.

A

Mr. George Bucknam Dorr assembled a

tireless walker and fearless climber, he

group of people who saw clearly and acted

enjoyed nothing so much as working out

wisely in organizing themselves into the

a good path up an incredibly steep crag

Hancock County Trustees of Public Res-

or finding a way between rock ledges to

ervations. Two years later the legisla-

some quiet grove hidden in a fold of the

ture of Maine confirmed the incorporation

mountain. His bovish excitement over

of the organization. Its purposes were

492

The National Park on Mount Desert Island

493

to receive, hold, and improve for public

he therefore realized that in order to keep

use the lands in Hancock County, which

it for the use of the people at large it

by reason of historic interest, scenic beau-

should become one of the national parks

ty, or any other cause were suitable for

under federal control. He, accordingly,

such an object." Seven years later the

went to Washington to consult Mr.

trustees received their first gift of land,

Franklin K. Lane, the Secretary of the

a tract on Newport Mountain, including

Interior, with regard to the acceptance

the Bowl and the Beehive, from Mrs.

of the tract by the government, under the

Charles D. Homans of Boston, one of the

Monuments Act, which allows the ad-

earliest of the summer settlers on the

ministration to set aside by presidential

island. Later in the same year Mr. John

proclamation lands of 'historic, prehis-

Stewart Kennedy of New York bought

toric, or scientific interest,' as national

the top of Green Mountain, the highest

parks, either when previously owned by

summit on our Atlantic coast, and gave

the government or when freely given it

it to the trustees to hold for the use of the

from some private source. Two more

nation. As the years passed, Dry Moun-

years' work on Mr. Dorr's part were spent

tain, the whole of Newport, Pemetic

in enlarging the boundaries of the park

Mountain (the only one still bearing its

still farther. and in searching and perfect-

Indian name), Sargent, Jordan, and the

ing the land titles of the reservation ac-

Bubbles were given to the trustees, and

cording to the high standard which the

they held an undivided tract, including

government requires. Mr. Dorr then re-

all the highest land and the high-lying

turned to Washington in June, 1916, with

lakes of the eastern part of the island.

the deeds of the property prepared for ac-

Mr. Dorr had given nearly twenty years

ceptance by the government, and with

of unswerving and-far-sighted devotion to

Mr. Lane's effective help and co-operation

the ultimate usefulness of the island, and

he was successful in obtaining the Presi-

The Kane path skirting the glacial basin of the Sieur de Monts Tarn.

494

The National Park on Mount Desert Island

dent's signature to the proclamation on

will show water-lilies and arrowleaf and

the 8th of July.

sheets of blue pickerel-weed, with are-

The new federal land was named the

thusa and pitcher-plants growing along-

Sieur de Monts National Monument in

side sundew in the bog near by.

memory of Champlain's friend and com-

Every one interested in any of the pro-

panion whose courage and hope for the

tean forms of gardening knows the ex-

future made the voyage possible. The

traordinary delight in the co-operation of

French expedition to Acadia failed after

the island climate. The cool nights fol-

a gallant struggle, but the names of the

lowed by clear, sunny days give herba-

Sieur de Monts and his associates will be

ceous plants a brilliance of color and vigor

kept in remembrance for all time in the

of growth which cannot be found except

name of the first national park on the At-

in the high Alpine meadows. As the wild-

lantic coast.

garden idea is developed everybody who

Although Mr. Dorr has given vears of

wishes to see the northern plant and bird

patient work to the creation of the new

life at its best will come to study on the

reservation, he feels that the future holds

island. Already a fund for one wild gar-

many chances for its further development.

den has been given in memory of a mem-

He looks forward confidently not only to

ber of a family who cared much for Mount

the maintenance of the present svstem of

Desert, and paths, now included in the

paths, but to joining distant points by

reservation, have been made and named

further communications. There are

after others who spent many happy sum-

giant-rock slides and wide ocean views,

mers there.

bold cliffs and quiet meadows which can

The Sieur de Monts Park is the first to

now be seen only after a painful struggle

be set aside in the crowded Eastern States,

with matted underbrush. Roads should

and it should be the forerunner of a long

be built in the park which will be un-

series of reservations, to preserve for the

equalled in their beauty of combined sea

public use their most interesting and va-

and mountain horizons, and while its wild

ried types of scenery. Those who love

charm should in no way be lessened, it is

Mount Desert call it affectionately "The

possible to make the different parts of

Island," and they are happy in the knowl-

the government land more accessible.

edge that its hills are safe, that the forests

The approaches to the Sieur de Monts

will be protected from fire and mutilation,

Park and its surroundings are being

and that in the time to come generations

studied under the wise guidance of Mr.

will follow them in search of the peace

Dorr, who is its first custodian. At his

and refreshment they have themselves

instance an offshoot corporation from the

found in the cool bracing air and sweet-

Hancock County Trustees of Public Res-

scented woods. The great gray hills be-

ervations has recently been formed and

long to the nation, and each year, as the

named the "Wild Gardens of Acadia,"

winter snows yield and the brooks are re-

and under its direction plans are being

leased, the birds will come back to their

made to establish wild gardens and bird

sanctuaries, the flowers will begin an-

sanctuaries on lands adjacent to the reser-

other summer, and men and women will

vation as well as elsewhere in the State

return to the reservation again and again

and in Canada The shady valley of a

to seek and to find rest and new strength

brook will be used to grow the great os-

in its beauty. And every one who comes,

mundas, trilliums, and other forest and

either now or in the future, should re-

moisture-loving plants; or a collection of

member that he owes a large share of his

rock-plants will be established on a slope

enjoyment to the clear vision, the wise

where saxifrages and their tiny fellows

development, and the self-sacrificing en-

will root deeply and bask in the sunshine,

thusiasm of the first custodian of the

or a water garden at the edge of a pond

park.

Epp, Ronald

From:

Eliot_Foulds@nps.gov

Sent:

Friday, August 12, 2005 1:36 PM

To:

Epp, Ronald

Subject:

Re: Acadia N.P. Compliance Study

Hi Ronald:

You know, several months ago, I was thumbing through that report as well and noticed that

language too. In 1993, I was not aware that the term bipolar was a medical term

describing manic depressiveness. I think that the term has really come into popular usage

since then, and now I am aware that my choice of the term was a poor one. I was trying to

describe the apparent chasm of difference between the personality of Dorr, vs. that of

JDR, Jr.

I was not trying to psychoanalyze the two!

Hope you are well.

Eliot

"Epp, Ronald"

To:

CC:

08/11/2005 04:08

Subject: Acadia N.P. Compliance Study

PM AST

Dear Eliot,

Recently I re-read a section of your "Compliance Documentation for the Rehabilitation of

the Historic Motor Roads, ANP, and wondered whether you were using clinical language in

the following quote from your Historic Overview on page 7: "Dorr was gregarious, outgoing,

and had an impulsive streak which made him rush headlong into projects, oftentimes without

a great deal of planning and forethought. This made him a perfect alter-ego for John D.

Rockefeller Jr. To be certain, Acadia N.P. owes its existence to the enthusiasm and

tenacity of George Dorr. The human aspects of the story of the cooperation between these

TWO BI-POLAR personalities makes the story of the park and the roads only more

interesting. "

Next week I'll be speaking at the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory on the

priorities that Mr. Dorr pursued during the early 20's when the MDIBL was being

established. Harvard Clinician Frank Epstein is also speaking on the same issue and in

conversations last week he described Mr. Dorr as "bipolar." As I think through the

symptoms of manic-depressive disorder I can't help but wonder whether you were thinking

clinically or whether you were using "bipolar" to more generally indicate their being at

different "poles" on specific issues.

I'd appreciate your insights into this matter. Thanks!

Ronald H. Epp, Ph.D.

Director of University Library &

Associate Professor of Philosophy

Southern New Hampshire University

Manchester, NH 03106

603-668-2211 ext. 2164

603-645-9685 (fax)

1

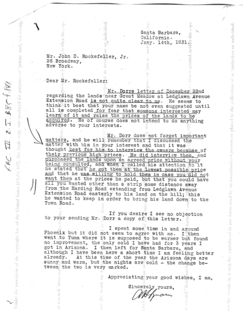

Santa Barbara,

California.

Jany. 14th, 1931.

Mr. John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

26 Broadway,

New York.

Dear Mr. Rockefellert

Mr. Dorrs letter of December 22nd

regarding the lands near Great Meadow at Ledglawn Avenue

Extension Road is not quite clear to me. He seems to

think it best that your name be not even suggested until

all is completed for fear that someone interested may

learn of it and raise the prices of the lands to be

acquired. He of course does not intend to do anything

adverse to your interests.

Mr. Dorr does not forget important

matters, and he will remember that I discussed the

matter with him in your interest and that it was

thought best for him to interview the owners because of

their previous high prices. He did interview them, and

purchased the lands upon an agreed price without your

being consulted, and when I called his attention to it

he stated that he got them at the lowest possible price

and that he was willing to hold them in case you did not

want them at the prices he paid, but that you could have

all you wanted other than a strip some distance away

from the Harding Road extending from Ledglawn Avenue

Extension Road easterly to his land on the hill; this

he wanted to keep in order to bring his land down to the

Town Road.

If you desire I see no objection

to your sending Mr. Dorr a copy of this letter.

I spent some time in and around

Phoenix but it did not seem to agree with me. I then

went to Yuma where it is supposed to be warmer but found

no improvement, the only cold I have had for 3 years I

got in Arizona. I then left for Santa Barbara, and

although I have been here a short time I am feeling better

already. At this time of the year the Arizona days are

sunny and warm, but the nights are cold - the change be-

tween the two is very marked.

Appreciating your good wishes, I am,

Sincerely yours,

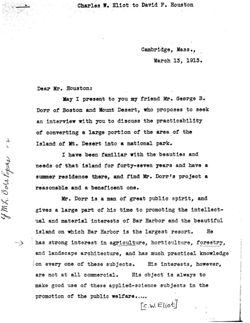

Charles W. Eliot to David F. Houston

Cambridge, Mass.,

March 13, 1913.

Dear Mr. Houston:

May I present to you my friend Mr. George B.

Dorr of Boston and Mount Desert, who proposes to seek

an interview with you to discuss the practicability

of converting a large portion of the area of the

Island of Mt. Desert into a national park.

I have been familiar with the beauties and

needs of that island for forty-seven years and have a

summer residence there, and find Mr. Dorr's project a

reasonable and a beneficent one.

Mr. Dorr is a man of great public spirit, and

gives a large part of his time to promoting the intellect-

ual and material interests of Bar Harbor and the beautiful

island on which Bar Harbor is the largest resort.

He

has strong interest in agriculture, horticulture, forestry,

and landscape architecture, and has much practical knowledge

on every one of these subjects. His interests, however,

are not at all commercial. His object is always to

make good use of these applied-science subjects in the

promotion of the public welfare

[c.W.Eliot]

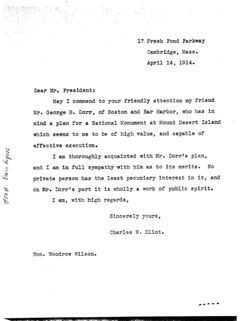

17 Fresh Pond Parkway

Cambridge, Mass.

April 14, 1914.

Dear Mr. President:

May I commend to your friendly attention my friend

Mr. George B. Dorr, of Boston and Bar Harbor, who has in

mind a plan for a National Monument at Mount Desert Island

which seems to me to be of high value, and capable of

effective execution.

centry

I am thoroughly acquainted with Mr. Dorr's plan,

and I am in full sympathy with him as to its merits. No

private person has the least pecuniary interest in it, and

on Mr. Dorr's part it is wholly a work of public spirit.

I am, with high regards,

Sincerely yours,

Charles W. Eliot.

Hon. Woodrow Wilson.

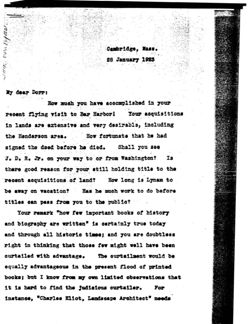

Cambridge, Mass.

28 January 1923

My dear Dorr:

How much you have accomplished in your

recent flying visit to Bar Harbor?

Your acquisitions

in lands are extensive and very desirable, including

the Henderson area.

How fortunate that be had

signed the deed before he died.

Shall you see

J. D. R. Jr. on your way to or from Washington?

Is

there good reason for your still holding title to the

recent acquisitions of land?

How long is Lynam to

be away on vacation? Has he much work to do before

titles can pass from you to the public?

Your remark "how few important books of history

and biography are written" is certainly true today

and through all historic times; and you are doubtless

right in thinking that those few might well have been

curtailed with advantage.

The curtailment would be

equally advantageous in the present flood of printed

books; but I know from my own limited observations that

it is hard to find the judicious curtailer.

For

instance, "Charles Eliot, Landscape Architect" needs

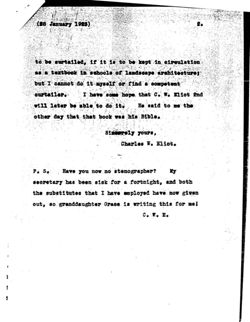

(28 January 1923)

2.

to be surtailed, if it is to be kept in circulation

as textbook in schools of landscape architecture,

but I cannot do it myself or find a competent

ourtailer.

I have some hope, that C. W. Eliot 2nd

will later be able to do it.

He said to me the

other day that that book was his Bible.

Sincerely yours,

Charles i. Eliot,

P. S.

Have you now no stenographer?

Ky

secretary has been sick for & fortnight, and both

the substitutes that I have employed have now given

out, so granddaughter Grace is writing this for me!

C. W. E.

1

1

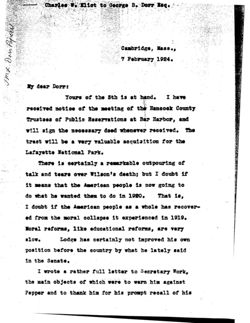

Charles w. Eliot to George B. Dorr Esq.

Cambridge, Mass.

7 Fedruary 1924.

My dear Dorr:

Yours of the 5th is at hand. I have

received notice of the meeting of the Hancock County

Trustees of Public Reservations at Bar Harbor, and

will sign the necessary deed whenever received. The

tract will be a very valuable acquisition for the

Lafayatte National Park.

There is certainly a remarkable outpouring of

talk and tears over Wilson's death; but I doubt 11

it means that the American people is now going to

do what he wanted them to do in 1920.

That is,

I doubt if the American people as a whole has recover-

ed from the moral collapse it experienced in 1919.

Moral reforms, like educational reforms, are very

slow.

Lodge has certainly not improved his own

position before the country by what he lately said

in the Senate.

I wrote a rather full letter to Secretary Work,

the main objects of which were to warn him against

Pepper and to thank him for his prompt recall of his

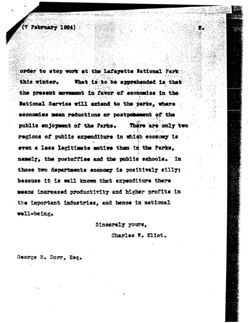

(7 February 1924)

2.

order to stop work at the Lafayette National Park

this winter.

What is to be apprehended is that

the present movement in favor of economics in the

National Service will extend to the parks, where

economies mean reductions or postpoment of the

public enjoyment of the Parks. There are only two

regions of public expenditure in which economy is

even & less legitimate motivo than in the Parks,

namely, the postoffice and the public schools. In

those two departments economy is positively silly;

because it is well known that expenditure there

mosne increased productivity and higher profits in

the important industries, and hence in national

well-being.

Sincerely yours,

Charles E. Eliot.

George B. Dorr, Esq.

of you as a rustling, pushing, abundantly successful

May

LO

get

things

teauy

101

College President. I want them to know you also as a modest

his garden. He was an ardent gardener, both in Maine and in

and tenderhearted Christian gentleman. So I welcome any signs

Cambridge. "Tired but happy," he wrote his wife from Asticou.

that lead me to hope that some day you will add to your

"I shall be stiff tomorrow from working unaccustomed muscles,

present reputation a kind of Mark Hopkins benedictory influ-

but who cares! It is seraphic here, cold as Greenland (I have on

ence" (1892).

two undershirts); the air is like champagne. Beecher and I have

Eliot made a habit of dropping in at his father's house on his

worked like Trojans setting out vines. I only hope they won't

way home from work and talking things over. On one of these

visits his father, at the time ninety years old with eyesight

1920

freeze tonight Tomorrow I shall take a dinner pail and spend

the wh ole day grubbing in the dirt."

almost completely failed, was as usual sitting alone in his study

When summer arrived and vacations began, three families of

in the dusk. Eliot had just come from a minister's meeting and

Eliots lived within stones' throw of each other. One of the

was describing it. "It's hard for me," he said, "to believe that I

activities in which all the families frequently joined was going

am now one of the veterans of our fellowship. Do you suppose

on picnics, which might include three generations, ranging from

that our younger ministers look up to me as I used to look up

four to seventy. Mrs. Samuel Eliot called them "Patriarchal

to Doctor Bellows or James Freeman Clark or Edward Everett

Picnics."

Hale?" His father opened his eyes and looked at his son deri-

'President Eliot was the prime mover, the organizer, the

sively and exploded, "Good God, No!" Eliot liked to tell this

enthusiast. A lovely, sunshiny morning would see him tiptoeing

story upon himself, adding that since that "deserved rebuke",

onto our piazza before breakfast, saying, 'How about an excur-

as he labelled it, he had not been able to take himself too

sion?' Then out of his pocket would come a sheet of paper on

seriously or to think of himself more highly than he ought to

which was written just who should drive, who should sail, who

think.

should walk, and the chosen picnic spot. It did not occur to

The Eliots had both a winter home in Cambridge and a

any of us that we might have preferences. Anyway, we never

summer home at Asticou in Northeast Harbor, Maine. It

dreamed of expressing them.

remained a mystery to the children, even after they grew up,

"At the appointed hour, the cavalcade started, climbing

how the family managed financially. The girls, in particular,

aboard carriages or boats, or trudging on foot laden with wraps,

remembered that they had to wear hand-me-down dresses and

a large tin can holding fresh water, and baskets of such 'spartan'

even sometimes dresses that came from the missionary barrel.

food as cold baked beans, cold fish, cold sandwiches - for the

When they were in their teens their mother's black suit, twice-

thermos bottle had not yet been invented. No alcohol, no cigar-

turned, was a visible sign of her self-sacrifice. Educational

ettes, no matches even, for all fires were forbidden

scholarships helped keep expenses down. Eliot's speaking and

"There were rules and regulations that had to be observed

writing netted him some welcome income. All he ever told the

and woe to the boy or girl who tried to pass an elder on a

children was: "I have always been able to earn an income

narrow mountain trail. I can see the line of marchers, led by an

sufficient for our rather simple tastes. We have never known

erect figure in a sun-helmet, the ladies following holding up

either the privations of poverty or the encumbrances of luxury.

ankle-length skirts, wearing shirt-waists with high, boned

I am well assured that that is the condition most conducive

collars, large hats draped in veils and, even, gloves. No bobbed

to contentment."

bare heads, no shorts, no socks. No indeed! A climb in those

Eliot took responsibility for the upkeep of the summer home

early days was one of dogged determination, decorum and

and grounds at Asticou, as long as his strength held out. They

sweat. Once on the mountain top, the elders would nap, the

included a good deal of woodland, which required frequent

young people pick blueberries and everyone enjoyed the beauty

cutting to keep open the view of the mountains and ocean. Not

all around, plus a satisfactory sense of accomplishment."

infrequently he went down to his summer place sometime in

When the children had grown up and acquired children of their

own they accepted with alacrity annual invitations to visit

150

Pilot of # Liberal Faith Samad Atknis Eliot

1862-195

Beacon Press.

Family Circle 151

Arther Cushman reg.fert Jr. 1976.

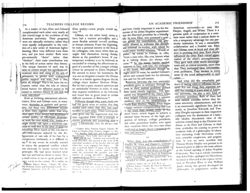

V. 54 (1952-53): 317-318.

306

TEACHERS COLLEGE RECORD

ligious sanctions and moral authority.

who protest against a stifling identi-

When churches do this, the public re-

fication of all human good with an

action in a morally dynamic society is

absolutist social-moral dogma. But the

sure to come. In our popular parlance

consequences of such moves in counter-

the churches "ask for it." But resolution

reaction will not be good if any minor-

Eliot and Gilman: The History of an

of the difficulty is not to be achieved by

ity, religious or otherwise, presumes to

reasserting the identification of the two

provide the moral authority and thus to

Academic Friendship

dimensions at the other extreme, wherein

speak for the whole community acting

the moral interest becomes the religious

in its own moral interest. The militant

WILLIS RUDY

interest and the authority of the former

minorities fulfill their mission as they

becomes a substitute for and excludes

ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF HISTORY, WORCESTER STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE

propose, initiate, and instigate changes in

the free development of sanctions by

the community's basic moral permissive-

the latter. Probably religions will, and I

ness and moral requirements. They are

The growth of American universities must

President Gilman, your first achievement

believe should, come into sharp relief in

parts of the community serving as cata-

arrest the attention of all who look back

here, with the help of your colleagues, your

these totalitarian lands as great orienting,

lysts as the whole people moves on

over the last half century.1 1

students, and your trustees, has been to my

thinking-and I have good means of obser-

directing, reassuring, sanctioning, com-

toward its own improved common forms

of moral authority.

T

HE year is 1901. The place is Balti-

vation-the creation of a school of graduate

forting, inspiring perspectives of those

more. The occasion is the public

studies which not only has been in itself a

celebration of the twenty-fifth anniver-

strong and potent school, but which has

sary of the Johns Hopkins University. A

lifted every other university in the country