From collection Creating Acadia National Park: The George B. Dorr Research Archive of Ronald H. Epp

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 51

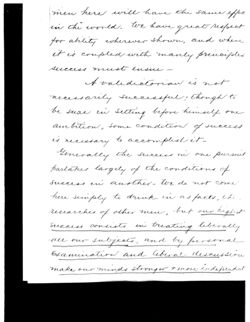

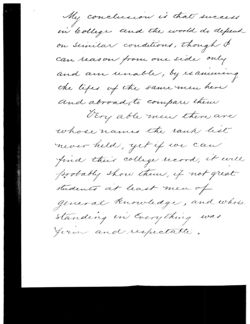

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

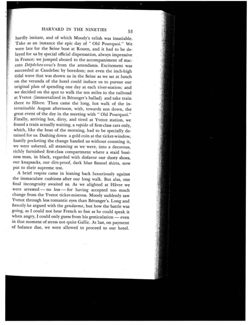

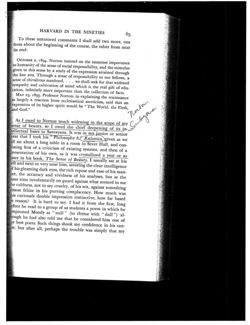

Page 57

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

Page 62

Page 63

Page 64

Page 65

Page 66

Page 67

Page 68

Page 69

Page 70

Page 71

Page 72

Page 73

Page 74

Page 75

Page 76

Page 77

Page 78

Page 79

Page 80

Page 81

Page 82

Page 83

Page 84

Search

results in pages

Metadata

[Series III] Harvard University-Libraries Evolution

Libraries Evolution

Harvard University:

The Undergraduate and the

Harvard Library, 1765-1877

HE gift from Thomas W. Lamont, Class of 1892, of a

T

million and a half dollars for the construction at Harvard

University of a library building primarily for undergradu-

ate use was announced by President James Bryant Conant

on the 2 ISt of November 1945. This gift, at one step, carries the Uni-

versity the greater part of the way toward the solution of a major prob-

lem of many years' standing, and consequently makes timely an account

of the problem in both its historical and contemporary setting, together

with a description of the concrete measures contemplated as a remedy.

This first article will cover the period up to the autumn of 1877, when

John Langdon Sibley retired and Justin Winsor took his place as Li-

brarian of Harvard College.> A second article, which will appear in the

Spring number of the BULLETIN, will deal with the period from 1877

to 1937, and a third, to be published in the Autumn number, will tell

of the development since 1937.

During the period covered by this first article, the Harvard College

Library had but two locations. The original Harvard Hall burned

down in 1764, destroying a large part of the Library. It was replaced

by the present Harvard Hall, which was completed in 1766. The Li-

brary at first occupied part of the second floor, but in 1815, after the

building of University Hall, the whole second floor was assigned to it.

Here it stayed until Gore Hall was ready in 1841, and no additional

space was provided until 1877.>Such library facilities as were provided

for use by the undergraduates were confined to these buildings.

The writer of this article is too cautious to attempt to state the exact

date when the need for an undergraduate library was first felt in Cam-

bridge. The first definite indication that he has found stems from the

fact that the College Records giving the laws for the Library on I 2

December 1765 quote from a previous law still in force, reading as

follows:

There shall be a part of the Library kept distinct from the rest as a smaller

Library for the more common use of the College. When there are two or more

setts of books, the best shall be deposited in the great Library & the others in the

29

HLBulletin I, # 1 (Winter, 1947).

30

Harvard Library Bulletin

great or small Library, at the discretion of the Committee for placeing the books.

This Committee shall also lay apart & with the assistance of the librarian prepare

a catalogue of such books, as they judge proper for the smaller library.

Among the new laws for the Library in the same year, 1765, No. 5

reads:

Whereas by the former laws, no scholar under a senior Sophister might bor-

row a book out of the Library, this privilege is now extended to the Junior

Sophisters, who shall both have liberty to borrow any books out of the smaller

Library. Each student in those two classes may also borrow books out of the

great Library, with the advice or approbation of their Instructors, procuring an

order under the hands of the President & any two of either Professors or Tutors

to the Librarian to deliver what book they shall judge proper for the perusal of

such student.

Vote 4, dealing with these Library laws, reads:

That the President Mr Marsh & the Reverend Mr Eliot be chosen on the part

of the Corporation to join with those who shall be chosen by the Board of Over-

seers, as a Committee for placing the books in the Library, that are to be lent out

to the scholars.

When the law of the Library which directed the preparation of a

catalogue of the books selected for the students of the College was put

into effect is not known, but there was printed by the College in 1773

a 'Catalogue of the Books in the Cambridge Library selected for the

more frequent Use of Harvard men who have not yet been invested

with the Degree of Bachelor in Arts.' It appeared over the imprint of

'Boston: New England, Press of Edes & Gill, 1773. It contained only

twenty-seven pages, and was an alphabetical list. The title page in Latin

reads: Catalogus Librorum in Bibliotheca Cantabrigiensi Selectus, fre-

quentiorem in Usum Harvardinatum, qui Gradu Baccalaurei in Artibus

Nondum Sunt Donati. Bostoniae: Nov. Ang. Typis Edes & Gill,

M,DCC,LXXIII. Following the title page was a "Monitum," or Note, in

Latin, explaining the need for the volume. A translation of this note

made by Professor Arthur Stanley Pease follows:

Inasmuch as the Catalogue of Books in the College Library is very long, and

not to be completely unrolled, when Occasion demands, save at very great

expense of time, embracing Books in almost all Tongues and about all Sciences

and Arts, most of which are above the Comprehension of Younger Students, it

has seemed wise to put together a briefer Catalogue, to wit, of Books which are

better adapted to their use. In the following Catalogue, then, in addition to

Classical Authors, there are included Books chiefly in the vernacular Tongue

Harvard University - Houghton Library / Harvard University. Harvard Library bulletin. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Library. Volume I, Number 1 (Winter

1947)

The Undergraduate and the Harvard Library, 1765-1877

31

and belonging to the general culture of the mind, omitting as much as possible

those which are in daily use in the College, as also those which are written in

foreign Languages, or which treat of specialized Disciplines, e.g., Medicine or

Jurisprudence. But let no one infer from this that Students are debarred from

the freer use of the Library.

Numbers attached to each Book indicate its place in the Library.

The numbers referred to in the last sentence of the note were four

items after each entry in the catalogue. The first apparently indicates

the alcove in which the book was found; the second the section in the

alcove; the third the shelf; and the fourth the number of the book on

the shelf. While the books in the list would not make exciting reading

for the present-day undergraduate, a comparison between this cata-

logue and the 358-page one which included the complete holdings of

the Library in 1790 makes it clear that there were books that were con-

sidered beyond the capacity of the average undergraduate in the eight-

centh century.

Certain details of the machinery governing the use of the Library

during this general period are succinctly recorded in an article on

'Harvard University: The Foundation and Growth of the College Li-

brary, which appeared in the Sunday edition of the Boston Herald,

I September 1878:

One great advance that America has made over Europe is in the freedom

granted to the users of books. No longer exists the old feeling that a constant

use of books would wear them out and leave none to posterity. No longer pre-

vails the thought that students must study texts and not read books. Less than

80 years ago this library was opened only two hours, with occasionally an extra

two hours a week. Then there were only three classes of persons - resident

graduates, seniors and juniors - admitted to the library, and these only once in

three weeks, respectively in the order above mentioned. They entered the

sacred portals three at a time in their alphabetical order. Until 1798 sophomores

could not enter. In 1810 the freshmen were admitted. Previously the latter had

never entered on their own account, but only as scouts or messengers, detailed

in parties of six to serve for the day. They were sent out in pairs to summon and

give notice of the approach of the squadrons of "three" that were expected by

the librarian. Their reward for this service was a sight of the precincts of the

library and the enjoyment of an exemption from one recitation.

Early in the nineteenth century, during what Samuel Eliot Morison

in his Three Centuries of Harvard calls the 'Augustan Age, the matter

of facilities for undergraduates was twice brought up by men who were

then Librarians of Harvard College. The central figure of this Au-

32

Harvard Library Bulletin

gustan Age was President John Thornton Kirkland. During his term

of office, the reputation of the University throughout the country was

rising rapidly, and Mr Morison states that a larger proportion of Har-

vard graduates of this period became distinguished than at any previous

or subsequent era. The Harvard Library at this time was beginning to

reach the stage when it was a factor in the life of the undergraduate.

Most American college library collections of the early nineteenth cen-

tury were made up chiefly of gifts and bequests; a large percentage of

their contents came from alumni who were or had been clergymen, and

it is not surprising that the volumes were more often than not theolog-

ical in character and were not as a rule of any particular interest to the

average undergraduate unless he was expecting to enter the ministry. >

The Harvard College Library throughout Kirkland's administration

was the lärgest in terms of number of volumes in the United States, and

also probably the highest in quality. The Hollis gifts had given it real

distinction and importance to scholars. The Ebeling purchase in 1818

raised it to the rank of a research library. There were enough books

that attracted undergraduates to make a problem for the custodians.

The term of office of the Librarian in those days was generally a

short one - forty-four men served in this position in the eighteenth cen-

tury - bukin 1813 Andrews Norton, later a distinguished professor in

the University, and the father of Charles Eliot Norton, became Libra-

rian, to serve for what was then considered a long term of eight years.

After Mr Norton had had an opportunity to study the situation, he

wrote in 1815 to President Kirkland a letter which indicates that the

question of a separate library for undergraduates was on the President's

mind and that a report and recommendations on the service to under-

graduates had been asked for. The report, which is quoted here in full,

leaves no doubt as to what the Librarian at that time considered the

proper solution of the problem. It reads:

Dear sir,

You requested me to state the advantages which I thought would result from

separating the books intended for the use of the Undergraduates from the Gen-

eral Library, and keeping them in a room by themselves, so as to form a distinct

library. It seems to me that the following would be among these advantages.

I. The object of a Library where valuable and rare books are deposited for

preservation, and for occasional use by those who will use them carefully, and

the object of one to contain common books for circulation among the students,

many of which from their continual use must be destroyed in a short course of

Harvard University - Houghton Library / Harvard University. Harvard Library bulletin. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Library. Volume I, Number 1 (Winter

1947)

The Undergraduate and the Harvard Library, 1765-1877

33

years, appear to be essentially distinct, and it would seem that both these

objects therefore ought not to be confounded together in a single collection of

books. In procuring books as the library is at present constituted, it is by no

means easy to consult at once two objects so distinct. It may be sometimes an

objection to procuring valuable books, that they are too expensive to be exposed

to the injury and destruction which they must be if suffered to go into common

use - or on the other it may be an objection to procuring common books that

we have already copies of them in the Library, though perhaps these copies are

too costly and valuable for circulation among the students - or it may be said

that it is not proper /wh. indeed seems to be the case/ to crowd the Library of

a University with such works and such copies of them as may be found in every

common bookstore. The difficulty I mention I think will be, and has been,

found greater in practice than it may appear at first sight. And even if this were

not the case, still it seems improper that the Library of a University should

contain such a heterogeneous assemblage of books as it must if a considerable

proportion of them are selected merely on account of their fitness for the use

of undergraduates.

2. It has been the practice till of late years to deliver to the students any book

indiscriminately from the Library that any one might ask for, with the excep-

tion of a very small list of prohibited books- most of which likewise were

prohibited only as being skeptical or immoral. The consequence has been that

many valuable works, and such as cannot be replaced, or replaced without diffi-

culty, have been injured and defaced. In addition to this, little attention has

been paid to procuring cheap editions of works of which there were costly ones

in the Library; but the latter have been suffered to go into circulation. The

Library has therefore suffered great unnecessary waste and injury. Nor are

either of these evils at present entirely remedied. Indeed the only remedy for

the first has been the Librarian's assuming the power of refusing such books, as

he thought it improper should be allowed to circulate among the students. The

first evil must continue in a considerable degree as long as the students are al-

lowed to use the General Library indiscriminately. It might it is true be rem-

edied by having a list made out of books which only, the undergraduates should

be allowed to use: even if these books remained in the same room with the others.

It seems to me that it would be only a further improvement to have the books

themselves separated. Nor would the making out of such a list prevent all the

inconveniences to which we are at present exposed.

3. For - either for the sake of preserving the books, the students must be

prohibited from reading and consulting them in the Library - or for the sake of

their benefit, they must be permitted to come in and use them as at present; or

in some similar manner. To continue the present practice subjects the Library

to considerable injury. Many scholars come in unacquainted with the value of

books, and without any thought of acting improperly, but from mere curiosity,

take down from the shelves a great number, and in doing so, use them without

much care: so that there is considerable gradual injury without any advantage

in return. In the present state of college, I do not think there is much to fear

34

Harvard Library Bulletin

from wanton mischief and depredation. Perhaps however it should be recol-

lected, that these will not be prevented by the good dispositions of the great

majority, but may be the result of the want of principle in a very few. After

the information which I have received from Mr Shaw respecting the Athenaeum,

and which I presume is known to yourself and the gentlemen of the corporation;

and after similar information which I have received respecting the College

Athenaeum of the Students, I do not think that there would be any reason to be

surprised, if a number of books were lost from the College Library during the

present year. - It is true that the evils which I speak of might be remedied by

prohibiting the scholars to take books for themselves from the shelves of the

Library; and requiring them to ask for any one they should want from the

gentleman attending. This however would be such a total interruption of his

time, /beside exposing him to a variety of vexations/ as no person would submit

to without a very considerable compensation. - If there were a particular li-

brary for the use of students, they might be admitted freely without any ill-

consequences of much importance. If books were injured or lost, it would be

only a pecuniary loss: as the books in such library would be for the most part

such as could easily be replaced.

There is another evil attending the present practice respecting the admis-

sion of undergraduates, which I do not myself however think /at least at

present/ to be a very serious one. Gentlemen of the government have sometimes

complained to me of interruption from the number of students in the Library,

many of whom come in from merc curiosity.

4. I believe if more attention were apparently paid to the preservation of

the Library by those who have the care of it; more attention would bc paid to the

same object by those who might continue to have the use of it. So many of the

books are now exposed to that sort of circulation by which they must soon be

defaced and injured, that scarce any one feels much obligation to be very carcful

of any book that he may borrow. There are none of those associations and

feelings connected with the library which there ought to be with one for the

preservation of valuable works. It is too open and too much exposed to the

worst sort of use. - I should think likewise that there would be more donations

of valuable books to the Library, if there were a greater certainty of their being

properly esteemed and carefully preserved.

5.(The appearance of the General Library would be much improved by sep-

arating from it the books particularly intended for the students, and forming

them

into a distinct library. Its shelves would not be so vacant as many of them

often are. The books which it would contain would not be so many of them

cheap and common; nor would there be such an appearance of injured and

defaced books as there at present is. - The books likewise would not be marked

and written in, sometimes indecently as I fear is even now done; and which

heretofore has been much more the case.

The advantages then of having two distinct libraries as has been proposed

seem to me to be generally these.

That the objects of both would be better consulted.

Harvard University Houghton Library Harvard University. Harvard Library bulletin. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Library. Volume I, Number 1 (Winter

1947)

The Undergraduate and the Harvard Library, 1765-1877

35

That the General Library would from various causes be far better preserved:

which I conceive to be the principal advantage-and

That its appearance would be much improved.

I have taken the liberty of addressing these statements to you personally, as it

seemed to afford the most simple form of making them. Whatever may appear

to you proper you can lay before the Corporation.

I am very respectfully, etc

/s/ Andrews Norton

No attempt will be made here to discuss the statements made by Mr.

Norton, but his letter does give what seems to be a clear picture of the

situation as it stood one hundred and thirty-two years ago. The Library

was apparently being used rather freely by undergraduates and the

Librarian was worried about the damage that the books were suffering.

He was enough of an old-fashioned librarian to feel that his first duty

was the preservation of books, and he was probably less interested in

their use than in their preservation. But he had come to the point where

he realized that undergraduates did need to use books from a library, and

he was ready to recommend in the year 1815 a separate library for

undergraduates. In the following year the Library records indicate

that a separate list of books for undergraduates was again drawn up in

order to help the situation.>

Norton was succeeded in 1821 by Joseph Green Cogswell, whose

term as Librarian continued only two years, but who was so active dur-

ing those years in recataloguing and reclassifying the whole Library

that the period is a landmark in its history) Later, as head of the Astor

Library in New York, Cogswell became one of the few American

librarians to make a real contribution to the profession before modern

library history began in 1876. His great interest was in library collec-

tions, and at the Astor Library he built the first well-rounded reference

collection in the United States. As might have been expected, he em-

phasized, during his term at Harvard, the contents of the Library and

the technical processes by which the books might be made available

rather than the actual service of the books. On 6 November 1822, he

made a long report to the Harvard Corporation which began with a

paragraph reading:

Having completed the arrangement of the Library in conformity to your

directions, I beg leave to lay before you the following account of its present

condition, & to subjoin a few remarks, explaining my views in relation to it.

36

Harvard Library Bulletin

Cogswell then proceeded to explain the Baconian classification that

he had installed. He told of his decision to make an alphabetical instead

of a classed catalogue. He brought up the question of the condition of

the Library and the need of binding many of the books. He reported

on the sale of duplicates, showing in this connection some trepidation

and fear that the Corporation might not approve of the action that he

had taken. He stated that the College Library consisted of 19,900

volumes, supplemented by 800 volumes in the Medical Library, 500

in the Law Library, and 380 connected with the Natural History Pro-

fessorship. He then continued as follows:

The foregoing facts furnish you with a full account of the present situation

of the library, allow me now to add a few observations upon it. The great ques-

tion to be settled before you determine what system is to be adopted & what

measures are to be taken in regard to its future management is, whether you

consider the principal purpose of it to be, to make a library for men of learning

or to furnish books for the accommodation of undergraduates: If the latter, it

is already far larger than necessary, if the former it is but a beginning, a single

star in the constellation which ought to beautify & illumine our part of the

hemisphere. I must suppose, that you prefer the most important of these objects,

or I have nothing to say; in this case, then, what should determine the choice of

books, to be selected for it? in my opinion the first circumstance to be observed

is rarity, not however entirely disregarding intrinsic value - rarity I mean,

which arises either from the voluminousness & value of the work, or from the

accident of its being out of print, or from the small number of copies originally

printed, or from its being one of a character & upon a subject to interest but

few & consequently to be owned but by few. This principle would bring in the

Byzantine historians in preference to Gibbon, Twysden's Scriptores Decem be-

fore Hume & Hickes's Thesaurus before Johnson's Dictionary & should it not be

so & where else could a scholar hope to find either of the three first named works,

if not in the principal public library in the country, & how easily might he find

any of the others at every turn. The next object is to complete the collection in

the several departments, to enable the enquirer to exhaust the subject of his en-

quiry, by the aids which you can furnish him: A library which is known to be

distinguished by either of these characteristics will be resorted to by men of

learning, & men desirous of becoming so. We have a few of the first described

treasures, & our department of American history is very near the degree of com-

pleteness, which would entitle it to receive the mark. I will mention one case by

way of illustration - there is a single 8vo volume, of no uncommon beauty, in

one of our Alcoves, entirely unknown to 999 of every 1000 who use the library,

which would sell quick in London for $75 or perhaps an $100, a sum which

would buy a good many classical dictionaries & Port Royal Gr. Grammars, &

even a few setts [sic] of Rollin & Ferguson & such like matter, - but where is

the champion of utility who would come forward & propose to exchange this

Harvard University Houghton Library / Harvard University. Harvard Library bulletin. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Library. Volume Number 1 (Winter 1947)

The Undergraduate and the Harvard Library, 1765-1877

37

copy of "Hearne's Acta Apostolorum" for its value in such books - how much

more pride would be felt in showing this copy of Hearne to a scholar, than in

having an hundred or two more volumes which are every where to be met with

to swell your Cataloguc - na more, would it not be better for the causc of

learning that this copy, the only one in the country I believe, of this very rare

book, of which there were originally but 120 copies, should be kept in case of

need, than that common class books without number, should be dealt out to

those, who might just as well be supplied otherwise. I well remember what

triumph it was some six or eight years since, that our library furnished to the

Abbe Cona a work not be found in Philadelphia & even to this day, whenever

we are spoken of in that American Athens, this is always told of us. It is true,

this is not worth much, but it serves to explain how a really learned library may

be serviceable to learned men & how the institution with which it is connected

may gain reputation by it. To sum up all I have said on this head, I would aim

principally to make the library subserve the wants of scholars, & not those of

common readers; common books every body owns, or can have access to, rare &

costly ones properly belong to those deposits, around which a learned commu-

nity collects.

But the library it may be said makes an essential part of the machinery of the

institution, which cannot go on without it. This is no doubt truc & I would by

no means propose to stop it, but merely to regulate it. The law requiring the

books for the Undergraduates to be designated, should be strictly enforced;

their Catalogue should be distinct & the books not upon it, should be the same

to them as if not in the library. Whenever a particular course of study or any

other circumstance made it expedient to depart from the regulation, it should be

done in a manner prescribed - No library book should be allowed to be used as

a class book under any circumstances, such a use being wholly inconsistent with

its proper preservation & with a due regard to the rights of others. If thought

necessary to aid the poor students in procuring their class books, it should be

done independently by the library & in a way to secure the College against loss.

Nothing whatever can prosper without system & order, & in nothing are system

and order more requisite than in the management of a library, by the aid of

these & of economy & good judgment in appropriating the scanty funds, which

it now has, a sensible & important increase may annually be made, but certainly

not upon the principle of buying 20 copies of one book, 10 of another & so on.

Allow me to ask your attention to the subject of a Catalogue as soon as may

be, as I am particularly desirous of bringing my work in the Library to a close.

In the hope of meeting your approbation, I submit the accompanying memo-

randa to your examination, trusting that whatever you may think of my judg-

ment, you will be persuaded of my fidelity in managing the concerns, which

have been entrusted to me.

I have the honor to be with

the greatest respect, Gentlemen,

Your most obt. svt.

/s/ Jos. G. Cogswell

38

Harvard Library Bulletin

Mr. Cogswell was not considered a conservative in his day. With

George Ticknor and Edward Everett, he had gone to Germany for

graduate study as the first group of the ever increasing number of

American scholars who in the next hundred years studied abroad and

did so much to determine the course of higher education in this coun-

try. He was one of the founders of the Round Hill School at North-

ampton, which, if not the first of our progressive schools, might well

be considered as one of the first to improve the status of American

secondary education. His great work in building up the Astor Library

and cataloguing it has already been mentioned. His influence on the

Harvard Library did not close with his two-year term in 1823, but

continued directly or indirectly all his long life, and in 1864, over forty

years later, after his retirement from the Astor Library, he came back

to Cambridge and was the friend and confidant of John Langdon Sibley,

who was Librarian of the Harvard College Library from 1855 to 1877.

If in library matters Cogswell was what we would now call conserva-

tive, he was at least a product of his time, and it is interesting to note

that in his early days at the Astor Library he wrote to George Ticknor

saying:

The readers average from one to two hundred daily, and they read excellent

books, except the young fry who employ all the hours they are out of school in

reading the trashy, as Scott, Cooper, Dickens, Punch, and the Illustrated News.

It is not surprising, then, that he decried the use of the general col-

lection at Harvard by undergraduates whose needs he thought could be

cared for in other ways, and his report quoted above confirms the letter

of Andrews Norton that there was a problem in regard to what the

Harvard College Library should do for undergraduates. Sixteen days

before Cogswell presented his report, he wrote to President Kirkland

to explain why he could not accept a Corporation appointment as

Librarian as follows:

The Corporation consider the most important object of it [the Library] to be

the accommodation of the undergraduates with books to facilitate them in the

prosecution of their elementary studies, & they are most likely to be right, but

I cannot come to their opinion, & I cannot persuade myself that the opportuni-

ties I have enjoyed are turned to good account in devoting my life to labours

which might as well be performed by any shop boy from a circulating li-

brary

Cogswell may have misjudged the Harvard Corporation, as that body

did not provide library facilities for undergraduates of a high enough

Harvard University - Houghton Library / Harvard University. Harvard Library bulletin. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Library. Volume Number 1 (Winter 1947)

The Undergraduate and the Harvard Library, 1765-1877

39

quality to prevent them, during this period and the two following

generations, from building up small book collections of their own that

went by the general term of Student Society Libraries. It is hoped that

the story of these libraries at Harvard will be told in this BULLETIN or

elsewhere in the not too distant future. It should be added, however,

that the Harvard undergraduates apparently received enough consid-

eration in the College Library so that their own student libraries did

not reach the full flower that was found at Yale and in many other col-

leges with smaller enrollments and less distinguished collections, but

the consideration received was not sufficient to quiet all complaints.

At any rate on I2 June 1848, President Edward Everett received a

letter written by Walter Mitchell of the Class of 1846, which inveighed

against the Library Rules. Mitchell had done more than creditable work

in college. He had won a Bowdoin Prize for an essay on the Roman

Catholic Church in America. After graduation he studied at the Har-

vard Law School and was admitted to the Bar. He later was ordained

in the Protestant Episcopal Church and became in due course a Divinity

School professor. He contributed to the Atlantic Monthly and wrote

two novels as well as poetry, and delivered the Phi Beta Kappa poem at

Harvard in 1875. His letter is so revealing of library conditions in the

Harvard of a hundred years ago that, in spite of its length, it is printed

here in full:

[Cambridge 12 June 1848]

Hon Edward Everett.

Dear Sir.

I have ventured to address you upon a matter which is deeply interesting to

myself and to that body of which I was but yesterday a member, - the subject

of Harvard College Library.

It is after long thought and with much hesitation that I do this. I cannot tell

how you may receive it, whether as an ill judged intrusion of crude opinions -

or as the act of well-meaning sincerity, that is its own sufficient apology.

But I have also felt that from the difference of our positions, there might be

some avenues of observation open to me, that were denied to you - and that the

views of one fresh from the habits, the prejudices and associations of under-

graduate life, might suggest something not altogether familiar or useless.

I have endeavoured to do this truly and respectfully - and I am the more

encouraged, knowing, though my experience was very brief, the kindness and

courtesy with which a student's wishes were always listened to by you.

It can hardly be that the gift of a degree is to be a sentence of banishment,

closing forever and at once the mutual confidences and sympathies of the Student

and the President - ] would rather hope that those who yet linger here; before

40

Harvard Library Bulletin

going forth into the world - have a place in your regard - and that however

you may look upon the request - you will not judge harshly of the asker.

It is in this hope; Sir - that these pages are submitted to your notice.

What is the present system of the library and what are the reasons for its

adoption?

The hours of admission are inconvenient, they are reduced - few as they

are - by the constant encroachments of the lecture and the recitation.

During one term in my junior year - there was left me but two hours in the

week when I could obtain books - this may be remedied now - but I scarcely

see how any arrangement of recitations can give to the student the full time

which he is nominally allowed. The days - when it would be most accessible

to

the student - are not library days - Friday afternoon, Saturday - and days

like the present - (the ist Monday in June) would be a large and a grateful

addition.

Nor is this scanty allotment of time made properly available.

Were you ever in the Library at the hour when a class are obtaining books?

You must have seen I think something of the difficulties I now write of.

The only way by which the student is to discover what the shelves contain

is the catalogue - seven or eight large volumes. It is not possible to use these

undisturbed for ten minutes at a time and the student has to find not only where

it is to be looked for - but what he wants.

The student comes here to learn his needs as well as to supply them. He

cannot be supposed to know of the existence even of the greater part of the

hoarded wealth those shelves contain.

Well for him if he have even a clue by which to find it - but he is not sent

to College with his brain already an encyclopaedia of authors - a compendium

of title pages - he must draw at random from the long list of unfamiliar names

- "hoping for the best and fearing the worst" Give him leave to enter and

select for himself - from among the books not from among their titles merely.

All that the lecture room and the recitation can do is to give him subjects for

study - to put him on the track of investigation - he cannot travel back to the

fountain head - by poring over the cat. twice a week - and carrying off to his

room one or two chance-selected volumes.

Place yourself, Sir, in the position of an undergraduate - You are interested -

many of us are [not as] idle as we may seem in the lecture room and at the

recitation - in the solution of an historical doubt. Your faith in the integrity of

Hampden - and the guilt of Wentworth has been shaken by some artful Royal-

ist - and you wish to examine for yourself.

Into contemporary memorials, speeches - letters - through different his-

torians - and tractarians your search leads - in the course of two or three hours

you would examine nearly a hundred volumes. - Seat yourself in the librarian's

room - and send for your books as you perforce must. After the first six re-

quests - the seventh will probably meet with an answer that will effectually put

to rest your spirit of inquiry - and probably send you indignantly from the hall.

I have no ill fecling towards the officers in charge of the library. Far other-

wise. Few in my class made more constant demands on them than I did-and I

Harvard

University

-

Houghton

Library

/

Harvard

University.

Harvard

Library

bulletin.

Cambridge,

Mass.,

Harvard

University

Library.

Volume

Number

1

(Winter

1947)

The Undergraduate and the Harvard Library, 1765-1877

4I

cannot now recall a single instance of discourtesy and neglect in anything that

was in their power to grant. I have many favours-and which, knowing the

strictness of the laws in force, I felt to be truly favours to thank them for.

But I put to [sic] to you, Sir, how is it possible for an officer - harrassed by

conflicting claims for assistance, sought by twenty different applicants at once,

to be otherwise than seemingly negligent and impatient, And how too is it pos-

sible for the student, especially the retiring or the high spirited, whom one sharp

word is enough to silence when asking a favour, not to be discouraged?

I have known, and not once or twice only, students to leave the hall unsatis-

fied - and feeling that they would not soon again expose themselves to such

unpleasant usage.

I can give from my own knowledge an instance of the extreme difficulty a

student meets with. While in College a student formed a plan of investigation -

to take a favorite book - Macauley's [sic] essays, I believe, - and marking

every allusion in it that was obscure to him to find and note down the explana-

tion. But he could not visit the library when he would - on his leisure days, in

his leisure hours, it was closed - he could not, when there, take down the vol-

umes from their shelves-nor could he venture to trouble the Jibrarian for a

book for which five minutes use would suffice, that officer had enough to do to

furnish those who were taking out books for the week - and it was too precious

a privilege to be wasted on books of references. Having proceeded with his plan

just far enough to be convinced of its usefulness to himself - he was obliged to

abandon it.

But this is not all - the student enters and leaves the hall with a character

hanging over him bad as that of a suspected pickpocket.

He is made to leave his cloak and cap at the door, that they may not serve to

conceal his spoils.

Across every alcove stands a bar forbidding him to enter. Into that pleasant

little chamber that forms the Eastern arm of the transept of which the very air

is redolent of study - he must not set his foot. Even the presence of a college

officer is no safeguard against the tinglings of dishonesty supposed to thrill in

student fingers. I was once ordered from the alcove into which I had gone with

Mr Torrey to select a French author in which to find material for a version-

thinking in such company the imputation might be for a moment suspended.

I am not aware that my case was peculiar. I was never detected in any

theivery [sic] in Gore Hall, nor if my memory is true, was I ever liable to be.

I presume any one of my sixty-five classmates would have been equally dreaded.

This may seem a little thing to those who are far above it - but it is a bitter

a humiliating consciousness to those upon whom it is laid - not the less so, Sir,

because unmerited - and I have known some who will and would never cross

that threshold - having once felt the degradation of such treatment.

What are the reasons of this policy, and the objections to a change to

introducing the same system now pursued in the law library? Onc reason is the

alleged depredation and injury to the books. But what, Sir, is the object of

the library? Were all those munificent donations given simply for the use of the

thirty or forty privileged persons who are permitted to use it - or for the gen-

42

Harvard Library Bulletin

eral use of the College? Will not all the losses under the most liberal estimates

of damage be overbalanced by the increased good accomplished? This is a

question for your own mind - I propose to look at another point. Does the pres-

ent system preserve the books from injury and depredation?

The books it is said may be marked and defaced while in the hands of students

and no one made responsible. They are now placed in the hands of the student

and credited to him so that every injury is traceable to the offender. Is this so?

I do not think deliberate wanton injury is feared. I cannot think that the mis-

chicvous spirit is so rife among undergraduates - that they are a set of destruc-

tive monkeys who pull in pieces all they lay hands on. Most of them have their

own little collections and know how dear 8 treasured volume may become to its

possessor.

The injuries feared are those of thoughtlessness and forgetfulness - marginal

notings, underscorings and marks of admiration. Now these are not to be de-

tected without a close scrunity. The librarian if he would make this regulation

answer its ends must examine each volume when received page by page or the

greater part of these defacings must escape his notice - and this must be done

every time or the blame will light on the wrong head.

That he does not do so, you are well aware, that he could not do so - is per-

haps equally clear - it would require a score of clerks in full employment More

than that - I have reason to know that no small proportion of the books that

leave the library leave it clandestinely.

You cannot prevent this - as long as you deny to the student the privilege of

using the books on the spot. He does not offend against his own moral sense by

so doing. He feels himself debarred from the free use of what was meant for

him to use freely, by restrictions that to him seem absurd and harsh and you

know that these petty restrictions sit lightly on a student's conscience.

This may seem inconsistent with what I have just stated - with the complaint

that the student is harshly and unjustly suspected - but it is not so. I am stating

facts - speaking for all classes, for those who will - and those who will not vio-

late the college laws. I wish to show that you insult the high minded and honor-

able by preventive laws that do not prevent - that you are trying the most irra-

tional of attempts to make power felt without making it benehcent, that you

suffer the student to slip into the alcove long enough to carry away a book-

not long enough to examine and replace it.

The only way that smuggling has ever been effectually broken up, I believe,

has been not by any improvement of preventive systems - but by a repeal of

the duties.

Let the student consult the books in the library, and depend upon it, Sir, he

will not be silly enough to run the risk of forfeiting his privileges, by carrying

them away without leave.

But this after all is not the thing feared - the student is not aggreived [sic]

because he and his classmates are suspecting [sic] of smuggling the volumes in

and out - but because he is accused of wishing to steal them - to carry them

away - not to use them - he cannot of course put them in his library but to

sell them to unscrupulous dealers.

Harvard University Houghton Library / Harvard University. Harvard Library bulletin. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Library. Volume Number 1 (Winter 1947)

The Undergraduate and the Harvard Library, 1765-1877

43

I remember one unfortunate instance, to which I need not allude more

pointedly, that has happened since I left college.

From the little I know of the guilty party I should not hesitate to pronounce

him not a perfectly free moral agent - there were many occurences [sic] in his

college career which would warrant the belief that there was a partial defect of

mind either inherent or induced - that took from the act its worst character.

You knew of the fact, but you could hardly know the strong pervading in-

dignation with which it was regarded by the undergraduates. And this was

done, too, in spite of the laws. Is it not, Sir, an axiom of legislation that restric-

tions that fail of their purpose are worse than useless?

But why not rely on the honour of the student? From your position you see

the worst side of undergraduate character. It is only when the student is coun-

selling mischief that his words are reported to you - when he is dissuading it

his voice never reaches so far. But you admit these young gentlemen to your

parlour without fear for the ornaments of your table. Mr Monroe and Mr

Nichols spread their counters with their most attractive works - and though the

costly volumes lie invitingly around - and no argus watches - the great distinc-

tions of meum and tuum remain inviolated. But as he enters Gore Hall the soul

of Barrington or Hardy Vaux takes possession of the hitherto ingenuous fresh-

man - temptation becomes irresistable [sic] - and nothing but the most rigid

laws - and the sleepless vigilance of three lynx-eyed librarians - and an assist-

ant porter can prevent an immediate and wholesale plunder.

Pardon me, Sir, if I have spoken too lightly, but I have felt this inconsistency

strongly.

Why not introduce the plan now in use in the Law library? That is open

from early morning till nine at night - the books are in every ones reach - there

are no forbidden alcoves or jealous officials, it is free to come and go without let

or hindrance. The rule forbidding loud conversation is enforced only by the

spirit of mutual gentlemanly courtesy - and it is well enforced. There are books

there which are valuable to the student not only as present helps but as future

needs, the actual tools of his trade - expensive, hardly won, to the poor almost

unattainable. Here is a strong temptation. I cannot believe the standard of

morality is so much higher in the Law School than in the College. The whole

character of the College - its higher requirements for admission - a certificate

of good moral character is one, - its stricter discipline purging it of all grosser

elements -- should make it a more exclusive circle, superior in morals and

manners.

What then is the actual loss of the law library? I have seen the librarian's

statements- the average loss for a term inclusive of text books furnished is

six volumes. This during the past year. Even these few are not certainly ascer-

tained to be lost. Many of the books are known under two titles and are thus

overlooked. Some are mislaid in the chambers of the professors - but sooner or

later the lost volumes come back almost without exception.

Is this slight loss a sufficient reason for shutting out the undergraduates year

after year from the use and the enjoyment of the best library in America. Was

it for this that so much time and wealth has been spent that the hoarded talents

44

Harvard Library Bulletin

should sleep, each in its napkin of dust - undiscurbed except by a periodical

migration from the northern to the southern alcove - and back again?

I have heard it said that students have no need of more time in and freer

access to the library - that they have quite enough to occupy them in the course

of study marked out. This may be the theory of college life - but it is not

the fact.

There are many here - no small part of each class, who are sent to college

not because they have any decided bent for study either in one branch or in all,

but to pass away those years that must come between their school days and their

entrance into active life.

They will not, they cannot be induced to give more time to the studies

appointed than is necessary to a tolerable appearance at recitations.

They are left to fill up many idle hours with more agreeable resources.

Now - those hours are spent in social visiting, in listless lounging, or still

more exceptionably.

If they are fond of reading, their resorts are now the Society libraries, and

that magazine of trash called the "Cambridge Circulating Library."

If they are not, the billiard room and the chambers of their classmates are the

place to kill their ennuied and miserable hours.

Would they not, Sir, if the library were thrown open to them, resort there

in preference?

If you ask for proof - see how cagerly and constantly they flock to the book-

stores where they can take up a volume without the interference of a janitor or

the suspicion of petty larceny.

And further more, Sir, is it not a change that you would gladly see? Would

it not lessen your cares and anxieties? Would it not be pleasanter when called

upon in the exercise of your duty to reprove a student for his neglect of college

exercises to feel that his derelictions had been in the direction of Gore Hall

instead of the billiard room and smoking club? And on the whole would not

such literary dissipation be far more likely to lead back active and gifted minds

into the paths of severer study than the coarse and feeble limitations of their

elder's debauchery which now entice the college rouès [sic].

But beside these there are many, who looking upon their college life in its

truest light feel that their days here are golden days and who gladly seek from

their Alma Mater the rich bounty she proffers.

Among them are different tastes - habits of thought and capacities - tending,

some to the one side, some to the other. It has not been the system of Harvard

to bind upon a procrustean rack of culture her various children - to send out

her alumni drilled like a regiment into uniformity and mechanical movement-

the present elective system evidences the wiser, freer policy of the great Ameri-

can University.

It is to such that the library should offer the means of development - to each

in his chosen path. It is from the lecture room and the recitation that the student

should come to follow out here the work that is there but half-finished - but

hardly begun.

I am afraid, Sir, the principle of emulation has been sometimes permitted to

Harvard University - Houghton Library / Harvard University. Harvard Library bulletin. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Library. Volume Number 1 (Winter 1947)

The Undergraduate and the Harvard Library, 1765-1877

45

encroach unduly upon the material objects of this institution, that in the anxiety

to make "first scholars" it has been sometimes forgotten to prepare for making

great men. Is it altogether improbably that the four years might not be spent

amid those books in free communion with them - quite as profitably as in the

ordinary course?

But in the fear lest the race for honours should not be fairly and hotly con-

tested - everything like help from without is steadily discouraged - and the

better editions of our text books put without our reach-lest we should gain

the start of some equally diligent but less favoured classmate.

You have been an instructor here, Sir, and must have known how necessarily

restricted the help given in the lecture and at the recitation must be - how much

is merely suggested - how much more passed over in silence. I was struck with

a recent remark of a college friend, as we were engaged in the law library in

following a train of investigation suggested in the lecture of the previous hour.

"How little we should have thought of doing this in College!"

And why? Not because we did not wish so to do, that we never were

puzzled by a difficulty - or allured by the brilliancy of a subject - but because

the labor of getting one reference, given us in the recitation, was rendered too

tedious .and formidable by the restrictions of the library. Take one book, used

-as a text book in College - Smyths lectures on History and estimate its com-

parative value used with and without access to collateral information.

What is learned for recitation - is ended with recitation. The spur of emula-

tion - the fear of blame - is sufficient for the hour, and ends with the hour-

what is acquired for its own sake does not depart so speedily. Is the object of

Harvard College, its true glory, to gratify its semi-annual committees with well

got up scholastic reviews - or to send into the world young men, who shall be

the foremost among good citizens and useful men.

It is the sncer of those who would decry the college that the student learns

only to forget - that the graduate even before his degree has been drawn from

its pink ribbons would make but a sorry figure at a preparatory examination.

We know that this is untrue, but is there not some shadow of foundation for

the charge?

One more word upon the present restrictions and I have done with them, at

least with their working upon the students feelings.

If I were writing to one who would ask of every reform Cui bono?" who

would try all issues by a material standard, I should forbear.

But with literary men the 'sweet influences' of books - the charm of

great

libraries- has been no infrequent or ungrateful theme. Many a passage of

eloquent enthusiasm must be familiar to you in praise of such retreats and by

you I do not fear to be misunderstood.

You can well appreciate the daily refining of the intellect, the ripening cul-

ture which this constant intercourse with those silent friends produces and

your own experience must have made you fully alive to the exquisite enjoyment

with which the lover of literature looks upon the collected treasures - th

garnered harvests of great minds - his pleasure in rare editions, his warmth of

greeting to old friends in newer and costlier dresses - the keen relish with which

46

Harvard Library Bulletin

he falls upon the feast of which he hitherto [has] been fed by scanty fragments.

You have been too, on classic ground and amid scenes of which every portion

have become historical - and none could better appreciate the privilege. But

how would you have felt to have entered your paradise of association watched

like a thief [sic] - to have been marched around the tomb of Achilles with a

sentinel at your elbow - and to have been met at the entrance of the Acropolis

by a placard of "No admittance"?

One further reason for this change is that it would furnish a common ground

where students and professors might meet more cordially. No one, if I have

rightly understood has been more interested in bringing about a more cordial

intercourse between the two than yourself, and I have the testimony of those

who more than twenty years ago were your pupils, to the pleasure and profit of

such an intercourse, and to your success in awakening a mutual interest and

sympathy in the studies in which you as professor they as undergraduates were

engaged. One of them, the Rev Wm H. Furness of Philadelphia, spoke to me

in the warmest terms of his grateful and pleasurable remembrance of that

intercourse.

I cannot think that all the difficulty is on the side of the student - but in the

recitation room it is hard to have it otherwise than as it now is. There is among

undergraduates 2 prejudice against those who seek for explanation after recita-

tions. It is considered to be for the purpose of currying favour, or as it is called

in cant phrase "fishing" - and it prevents many who really wish aid from asking it.

It is an unreasonable - but 8 powerful feeling. The most influential minds in

a class are those who generally least need or are least inclined to seek assistance,

and they have not found it their interest to combat the prejudice.

Could this place of meeting be once thrown open it would silently but surely

cure this evil.

Nothing in the intercourse of the late Judge Story with his pupils is spoken

of with such kind affectionate remembrance as the daily meetings with him in

the library of Dane Hall.

I have written these pages, Sir, with the earnest feeling that has been growing

and gathering strength for years. I know that in them I but utter the language

and give expression to the wishes of those beneath your charge.

If I have spoken unwisely, I ask but one more favour -- that you will forget

this communication and its author as speedily as possible.

I trust I have not given offence, but "I could not choose but write" - and as

I thought and felt I wrote. I could do no otherwise.

It will profit me nothing - a few days more and Cambridge so Jong a home-

will be to me only a place of pleasant memories-but I shall hear with most

sincere gratification of those changes which would have made it still happier

to me.

With grateful remembrance, Sir, of your past kindnesses -

I remain very respectfully yours

/s/ Walter Mitchell a

member of the Class of 1846

Harvard University - Houghton Library / Harvard University. Harvard Library bulletin. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Library. Volume I, Number 1 (Winter 1947)

The Undergraduate and the Harvard Library, 1765-1877

47

On 13 June 1848, the day after President Everett received Mr

Mitchell's letter, he replied to it as follows:

Dear Sir,

I have read with interest your well-written paper on the use of the Library,

& will lay it before the Corporation, within whose control, & not that of the

Faculty, the Library is. -

The subject is involved in difficulty. It has ever been the wish of the Cor-

poration to make the library as widely useful as possible: - And no public li-

brary in Europe or America, with which I am acquainted, is more liberally

administered -

Still I wish it were in our power to throw it more widely open; & the ques-

tion whether this is possible, is well worth a careful consideration.

I remain, very truly

Yours

/s/ Edward Everett

No notice has been found in the Corporation Records that President

Everett ever laid the matter before that body. Since he resigned the

next year, it may have been that he was too busy with other concerns,

or it might be that he was simply living up to his well-earned reputation

of being a do-nothing administrator.

Viewer Controls

Toggle Page Navigator

P

Toggle Hotspots

H

Toggle Readerview

V

Toggle Search Bar

S

Toggle Viewer Info

I

Toggle Metadata

M

Zoom-In

+

Zoom-Out

-

Re-Center Document

Previous Page

←

Next Page

→

[Series III] Harvard University-Libraries Evolution

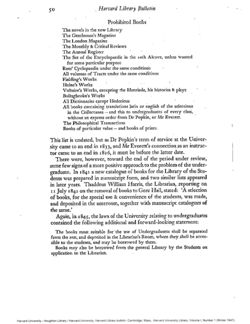

| Page | Type | Title | Date | Source | Other notes |

| 1-24 | Journal Article | The Undergraduate and the Harvard Library, 1795-1877 / Kevin D. Metcalf | 1947 | Harvard Library Bulletin I, #1 | - |

| 25-39 | Website | Chronology of Events in Library Preservation at Harvard / Sarah K. Burke | 2010 | From preserve.harvard.edu | - |

| 40-43 | Journal Article | The Harvard Library Loses Its Leading Faculty Supporter | - | Harvard Library Bulletin | - |

| 44-51 | Journal Article | The Library of the Department of Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning | 1953 | Harvard Library Bulletin , vol. VII, 2 | - |

| 52-56 | Notes | A college life... | - | TOR Appleton Papers B.5.F.10 | - |

| 57-84 | Journal Article | At Harvard in the Nineties / Daniel Gregory Mason | 1936 | New England Quarterly, 9 | - |